Uncovering the Layers of One of Pop Culture’s Most Influential Icons

Guest post by Olivia Turner, curatorial assistant, Meadows Museum, Dallas

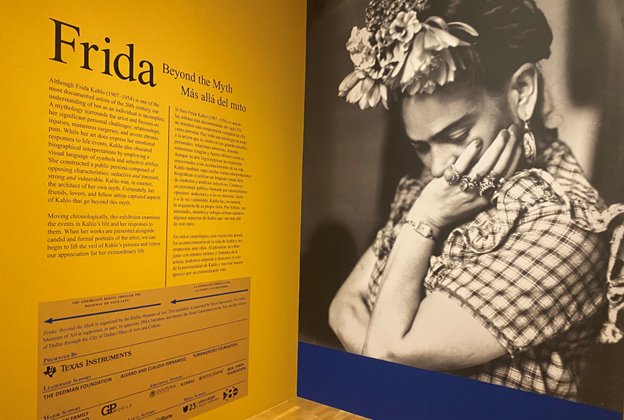

In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) is presenting an exhibition featuring over 60 works by and about Frida Kahlo. The selection of works includes 16 paintings, 12 drawings, 2 works on paper (one of which is Kahlo’s only known linocut), and 31 vintage photographs.

“Frida Mania”

Although Frida Kahlo experienced only two solo shows during her lifetime, she is now one of the most documented and exhibited woman artists of all time. This year alone, 20 exhibitions around the world are dedicated to her. Five of these focus specifically on photography, similar to this exhibition, Frida: Beyond the Myth. Before this show, the Dallas Museum of Art featured her work in the 2017 exhibition Mexico 1900–1950. In 2021, the museum also presented a more focused exhibition showcasing five of her works.

When conceiving an exhibition, one of the most critical questions to address is: What new and exciting perspectives does this show bring to the forefront? Exhibitions should not merely rehash familiar narratives, but instead offer fresh insights or innovative approaches to an artist’s life and work. Frida: Beyond the Myth faces a significant challenge in this regard. Kahlo is not only one of the most iconic artists of the twentieth century, but her life story has been widely mythologized in popular culture. The exhibition claims to “show us Frida as she saw herself,” which is a bold statement given the deep personal narrative Kahlo wove through her own work.

To stand out, the exhibition must balance celebrating her iconic status while also peeling back the layers of artifice surrounding her persona. This review will assess how effectively this goal was achieved by focusing on key individual elements of the exhibition. It will consider the curatorial choices, the variety of media, and the juxtaposition of her works with the photographs and portraits created by others. Through this analysis, I aim to determine what fresh perspectives, if any, this show brings to the ongoing fascination with Frida Kahlo.

Exhibition Text

The exhibition is organized chronologically, with each text panel guiding viewers through a significant decade of the artist’s life. Alongside her professional triumphs, the texts also detail her physical and personal hardships. These include her early battle with polio, the life-altering bus accident she suffered at age 19, her tumultuous and adulterous marriage, and her three known abortions. The text panels present these tragedies with a matter-of-fact tone typical of standard displays. With many artists, especially those who have passed, it can be easy to forget that they were human beings with complex lives. Since one of the primary goals of this exhibition is to humanize and demystify Frida, some of these details felt somewhat invasive—not to mention extremely gendered—at first glance.

However, following the legacy of many great artists before and after her, she used art as a form of medicine and therapy during her prolonged periods of convalescence. These experiences were central to her identity and deeply influenced her artistic production. As a newcomer to Frida’s story, I was aware of her struggles and physical ailments, but I had no idea they were so extensive. While some of the information felt intrusive, it ultimately serves to construct a comprehensive and human portrait of Frida Kahlo.

Diversity of Media Represented

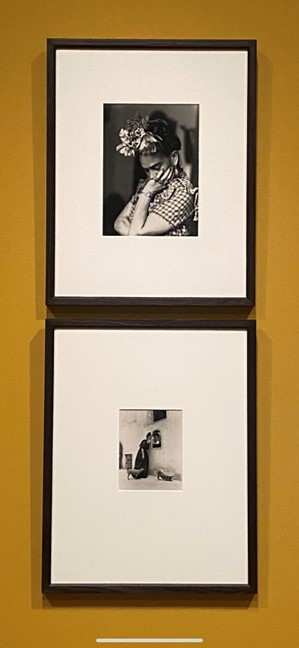

The checklist, featuring a diverse range of media, is one of the exhibition’s strongest points. Getting to know an artist through their explorations of different media, alongside photographs and portraits that they inspired, is a unique and rewarding experience. A particularly striking example of this synergy is the pairing of her Still Life painting with a photograph of her creating it. Seeing a photograph of the work’s creation process displayed alongside the finished piece was profoundly moving. Witnessing the physical conditions that shaped Frida’s final years of artistic production added an even deeper impact.

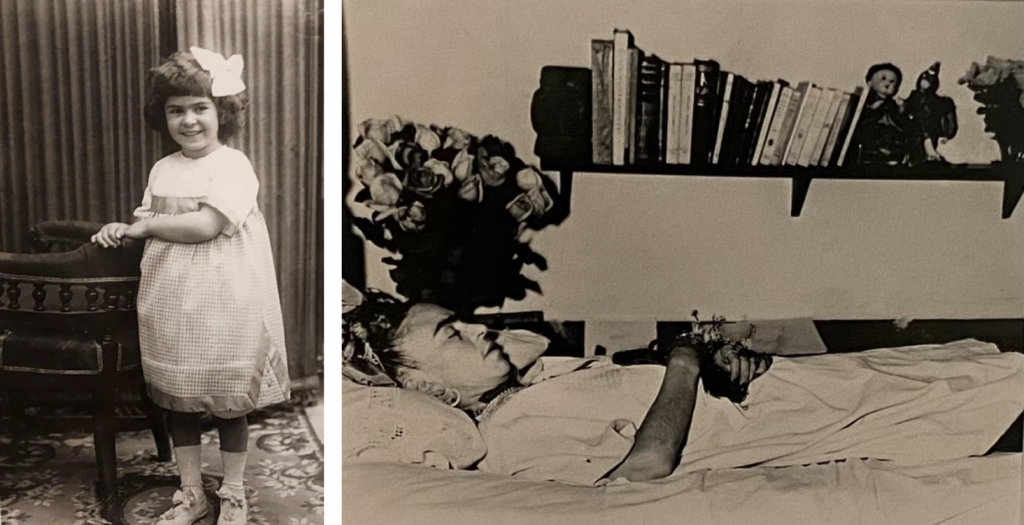

Another highlight of the exhibition is the selection of photographs, which offer a visual timeline of Frida’s life from childhood to her untimely death. Frida expressed her unique language of magic realism through various media. Early on, she developed an appreciation for photography by assisting her father, Guillermo Kahlo, a well-known photographer in Mexico City, in developing his photographs. Despite the fantastical style often seen in her work, Frida insisted that these dreamlike scenes were her reality—there was nothing surreal about them. This juxtaposition of her imaginative art with the documentary power of photography creates a compelling narrative, allowing the viewer to see both the fantasy and the reality that colored her life.

“I paint self-portraits because I am the person I know best. I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to and I paint whatever passes through my head without any consideration.” – Frida Kahlo

Activation

Although I visited the exhibition about a month after it opened, there were a substantial number of visitors in attendance. Most of the interactions I observed among the audience revolved around the photographs, which I believe speaks volumes about the show’s impact. These images offer an intimate and authentic glimpse into the life of a person who many may only know as an icon, perhaps primarily recognized through her otherworldly self-portraits.

The exhibition is held in a space typically reserved for the DMA’s smaller temporary displays, which I felt was ideal for the number of objects featured. The area was divided by translucent screens printed with an image of the Casa Azul, Frida’s home in Coyoacán, Mexico. This design element added a playful touch while also referencing the immersive experience that her house has become.

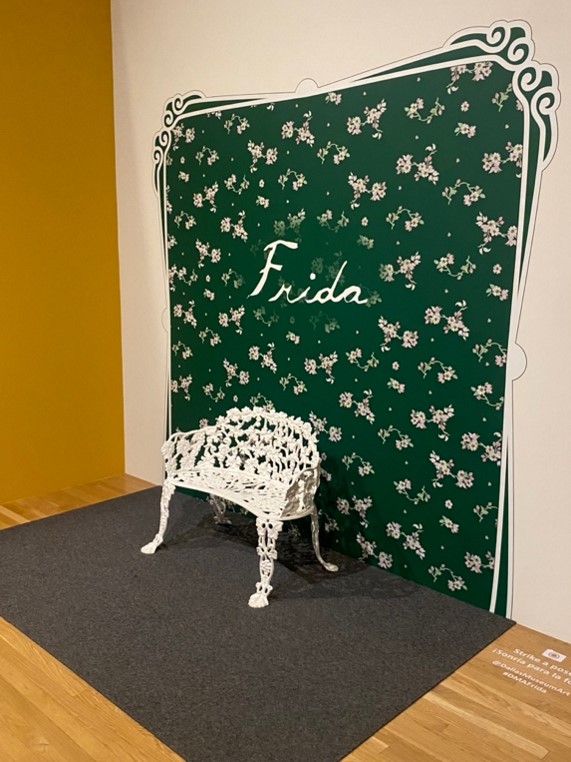

Despite the space’s modest size, there were several interactive moments throughout. One notable feature is the placement of a white bench against a lush backdrop, providing visitors the opportunity to rest or recreate Nickolas Muray’s famous portrait, Frida on a White Bench, which is on display nearby.

The in-gallery activities feature two tables integrated into the space, each offering a distinct experience. One table invites visitors to create a Frida doll, while the other encourages decorating her self-portrait. Both activities aligned with the exhibition’s ethos of deconstructing and reconstructing the artist’s identity from the viewer’s perspective. The gift shop also offers a diverse array of “Frida”-themed products, including books, gift items, and t-shirts.

Conclusion

The exhibition aims to lift the veil of Frida’s artifice and demystify her. I wondered whether she would have welcomed such an approach, as she carefully constructed and preserved her persona throughout her life and body of work. There is something lovely and humanizing, however, about seeing Frida through the perspectives of her friends and fellow artists. Though she seemingly viewed herself as her own muse, this exhibition celebrates her as a muse to many others. I believe Agustín Arteaga, DMA director and exhibition curator, perfectly captures the exhibition’s intent with the following statement: “Through this exhibition, we hope to peel back some of the layers to reveal more about the individual who continues to captivate audiences here and around the world.”

While we may never truly know Frida as she saw herself, I feel fortunate to have witnessed the peeling of some of these layers. After visiting Frida: Beyond the Myth, I gained a deeper understanding of one of the most significant artists of our time. Perhaps more importantly, I also recognized the profound impact she had on those around her.

Frida: Beyond the Myth is on at the Dallas Museum of Art until November 17, 2024. The exhibition will travel to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in April 2025.

Olivia Turner is the curatorial assistant at the Meadows Museum in Dallas, Texas, and a museum education intern at the Nasher Sculpture Center. She holds a Master’s degree in Art History from the University of Alabama, where her thesis examined the circumstances of women artists in early modern Seville, focusing on the daughters of Seville’s workshops and the career of Luisa Roldán. Olivia’s research interests center on women artists of the early modern period, particularly their roles within religious and cultural contexts. During her time in Dallas, she also completed a graduate certificate in Art Museum Education from the University of North Texas, enhancing her skills in both curatorial practice and museum education.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real Review, by Olivia Turner

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2024

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattler

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske