Guest post by Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Newberry Library

Rarely does a major cultural institution host an exhibition for an artist who is not already represented in its collections. Even more rarely does such an exhibition feature a female artist. When I walked into the Art Institute of Chicago’s Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, I knew nothing about her, but when I left, I had to know more. (Fig. 1)

Varo’s truly surreal blend of modern materials with the alchemy of medieval craft is unforgettable. The show is deftly curated by two more women, the Art Institute’s Caitlin Haskell, and Varos-specialist and independent curator Tere Arcq. It boasts over twenty paintings and many works on paper covering approximately the last decade of Varo’s life. At that point, the Spanish-born artist (1908–1963) was established in Mexico City and financially independent enough to focus on non-commercial work.

Thus, the show features her most self-assured style. Her luminous paintings on gessoed hardboard supports built up in many layers, glazes, and textures are reminiscent of the delicate brushwork of tempera or miniature painting of much earlier eras. The ambiguously gendered, repetitive faces in crowds transfixed by a magician, or blandly following after nuns, also bring to mind the characters of Israhel van Meckenem’s fifteenth-century Passion series, among other early engravings.

The Installation

The gallery space is organized into three main sections, two of which mainly contain moderately-sized paintings. The culmination is a large triptych in the final room. (Figs. 2-3)

An intriguing, loosely encased central space is filled with Varo’s preparatory graphite drawings, notebooks and geological specimens. On display here are some of her signature moon-activated crystals, with which she rubbed and scratched her paintings. This enclosure softens the lighting and shifts the palette of the art to grayscale from her usual subdued jewel tones. The exhibition unfolds throughout on an intimate scale. It neither skimps on artworks, nor overwhelms the viewer, even though the minutiae of Varo’s surfaces demand close looking. Happily, the exhibition, website, and catalog all discuss in detail the importance of the novel materials and techniques Varo used. Here are a few ways she employed them with both contemporary and age-old resonances.

Working Paper

The cloistered central works-on-paper section helps illuminate the beginnings of Varo’s artistic process. Most of the graphite drawings on view there correspond at exact scale to paintings in the outer rooms. The crystal specimens, sketches, and detailed calculations in the notebooks speak to the wide-ranging theoretical underpinnings of Varo’s art. As the photograph of the artist featured in the exhibition introduction attested, she would build the paintings up with rubbings, micro-scratches, and other textures, background first. She used the drawings to trace in ghostly apparitions of the figures last. Including actual crystals in the vitrine with the notebooks reinforces their status as central tools to her multimedia process.

Varo made her Disturbing Presence drawing in preparation for transfer to a painting, although one that is not on view. (Fig. 4) This warmly-toned sheet of translucent paper reveals a seemingly female figure seated on an ornate chair behind a table. A man’s head protrudes abruptly from the cushioned upper part of the chair, and lewdly extending his tongue, seems about to lick her neck from behind. The ethereal seated figure’s wry expression suggests both that she is not amused at being disturbed, and yet that she is grudgingly resigned to it. Domestic disruptions of that ilk have clearly happened before. Puncturing the appearance of reality with her incisive lines on the skin-like surface, Varo’s treatment of this uncanny interaction feels Odilon Redon-unreal, but also critical of this non-consensual act.

Inlaying Mother-of-Pearl

While Varo’s use of crystal rubbings created additional surface texture and occasional deeper, more dramatic scratches, a technique closer to engraving is perhaps her most illuminating.

One of the most compelling techniques on view at a spectacular 2022 Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition, Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish Americas 1500–1800, was the use of enconchado, mother-of-pearl inlay, in seventeenth and eighteenth-century paintings, particularly of devotional subjects. While paying homage to those saints by surrounding them with literally precious, studded sections of nacre, the effect was dazzling, but could also become flattening and decorative.

Instead of using abstract shapes, Varo seamlessly embedded the mother-of-pearl accents into the hardwood-like, gessoed masonite in careful silhouettes. She also inscribed and painted delicate faces onto this luminous material, but not so frequently that these passages become cloying or overly precious in both senses of the word. (Figs. 5-6) Varo used these for newly self-aware characters who had undergone “crystallization.” With such a selective touch, and an unexpected tendency to catch the light, those figures, like the flute player in a dangerous landscape, become instantly otherworldly. While the player is transported by attention to their own music, the erupting volcano in the distance hints at current events. As the catalog describes in detail, Varo and others flocked to the base of the erupting Paricutín volcano in Michoacán in 1943 to witness the devastation and natural forces firsthand. Artists over the centuries have proven similarly fascinated with rockslides and, by the eighteenth century, Vesuvius. The nearby eruption was evidently still on Varo’s mind twelve years later.

Painting Bone

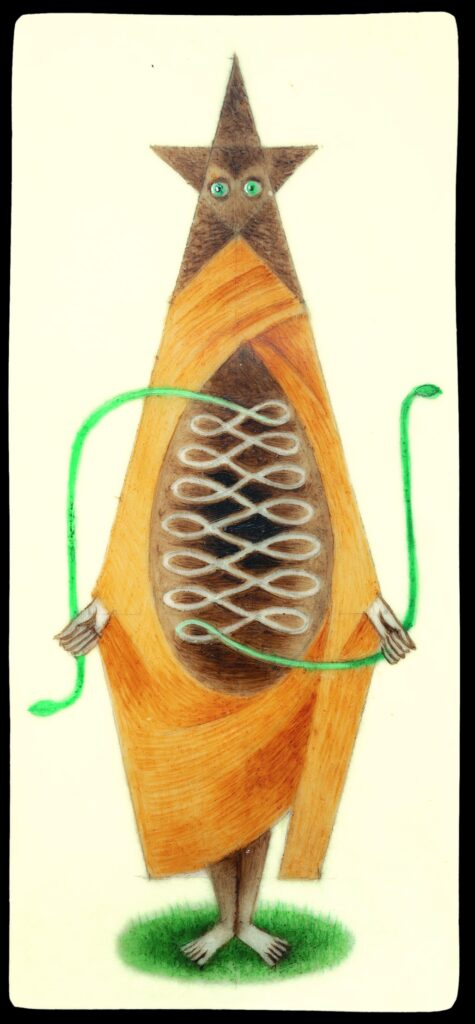

Although painting was central to Varo’s output in this period, hardboard was one of several types of support. One attention-drawing piece was also the smallest, a rectangle the size of a playing card showing a single, inscrutable standing figure. (Fig. 7)

Wearing a star mask, they hold the green-tinted, snakelike ends of their own orderly, bloodless entrails. The image is both a mysterious evocation of magic and the tarot tradition and also, humorously, somewhat reminiscent of a banana. The support is not paper or toned gesso, but a polished sheet of bone, another traditional means of increasing the luminosity of painted surfaces. The resulting luster is warm and inviting, and the detail of the tiny brush strokes akin to medieval miniatures on vellum or eighteenth-century portraits on ivory. But this was not Varo’s most surprising use of this material.

Sculpting Bone

Many of the elements of Varo’s paintings draw on the distant past; in at least one instance however, she also created her own literary backstory. Most of the books in the exhibition have been relegated to the central enclosure, but one key exception appears in the final room near the triptych. An illustrated manuscript text “discovered” by her one-time pseudonym, the scientist Hälikcio von Fuhrängschmid, accompanies an equally P.T. Barnum-esque construct of delicate animal bones recycled from her kitchen. (Fig. 8)

This, the so-called Homo Rodans, is cleverly displayed in an upright vitrine as if it were a real specimen of an alternate evolutionary option for man, if humans had developed a built-in wheel and a duckbill! Smaller than the shrunken Barnum “mermaid,” this being measures a bit over a foot tall. Varo also peppered the manuscript pages with lively gouache drawings of the creature in varied poses and a suggestion for how it would have looked with its skin reattached. The book invents an elaborate context of academic anthropological arguments over this nonexistent creature that themselves result in no new knowledge, only in-fighting. Iconic and unlike anything ever seen before, the bones themselves furnish the real story as the creature’s supple spine curves into a unicycle-like wheel, fusing technology and evolution, life and death. By framing the sculpture and accompanying text with so many layers, Varo’s ambulatory, bony tall tale lets the viewer (mostly) in on the joke.

Painting Science Fiction?

The final part of the gallery features Varo’s epic triptych. In it, her protagonist eludes the bonds of ecclesiastical authority, setting out on a journey of self-realization, and escapes with her lover in an impossibly tiny, furry boat. (Fig. 3) The grand narrative thrust of this unique series in her oeuvre makes one wonder, what kinds of science fiction did Varo read? The catalog describes the well-read artist and poet communities in Mexico City, and includes an intriguing appendix of relevant items from Varo’s library to support the exhibition’s subtitle, “Science Fictions.” She evidently read a great deal of Aldous Huxley (Brave New World among the books by him), Ray Bradbury, and even Sigmund Freud. One wonders whether Varo’s “paintings infused with thaumaturgy” and her Homo Rodans being of reconstructed bones would have made her a fan of Tamsin Muir’s Locked Tomb series with its powerfully unstable, interstellar female bone magicians. Muir’s own growing legions of fans would unquestionably also love Varo herself.

Conclusion

Literary aspirations aside, all of Varo’s paintings spoke to me deeply as a scholar of old master prints, books and Renaissance art, as well as evoking something totally new and original. Her medievalizing creations are magically, alchemically layered, with the palpably lingering aura of crystal-inscribed surfaces, and refreshingly unprecious mother-of-pearl accents. Witnessing these glorious idiosyncrasies makes for a personal, even subliminal encounter, and the effect resists reproduction. Her intentionally ambiguous narratives and sly humor photograph well enough, but the physicality of Varo’s work proves more subtle and ever difficult to grasp. This is an exhibition you have to see for yourself.

Remedios Varo: Science Fictions runs through November 27, 2023 in Gallery 289 in the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago. The excellent catalog has sold out at the Art Institute’s museum shop, but will be reprinted.

Suzanne Karr Schmidt is the George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at Chicago’s Newberry Library, and the newly-appointed director of the Movable Book Society, an international organization for artists, paper engineers, and collectors of pop-up books. In both capacities she fosters research and oversees exhibitions about interactive artworks on paper from the beginning of print, including the Newberry’s summer 2023 blockbuster Pop-Up Books through the Ages. While serving previously as assistant curator in Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, she curated Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life among other exhibitions about the materiality of printed images and texts. She actively shares her discoveries online (@drkarrschmidt).

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by novelist Paula Butterfield