Guest post by Andrea Sluder West

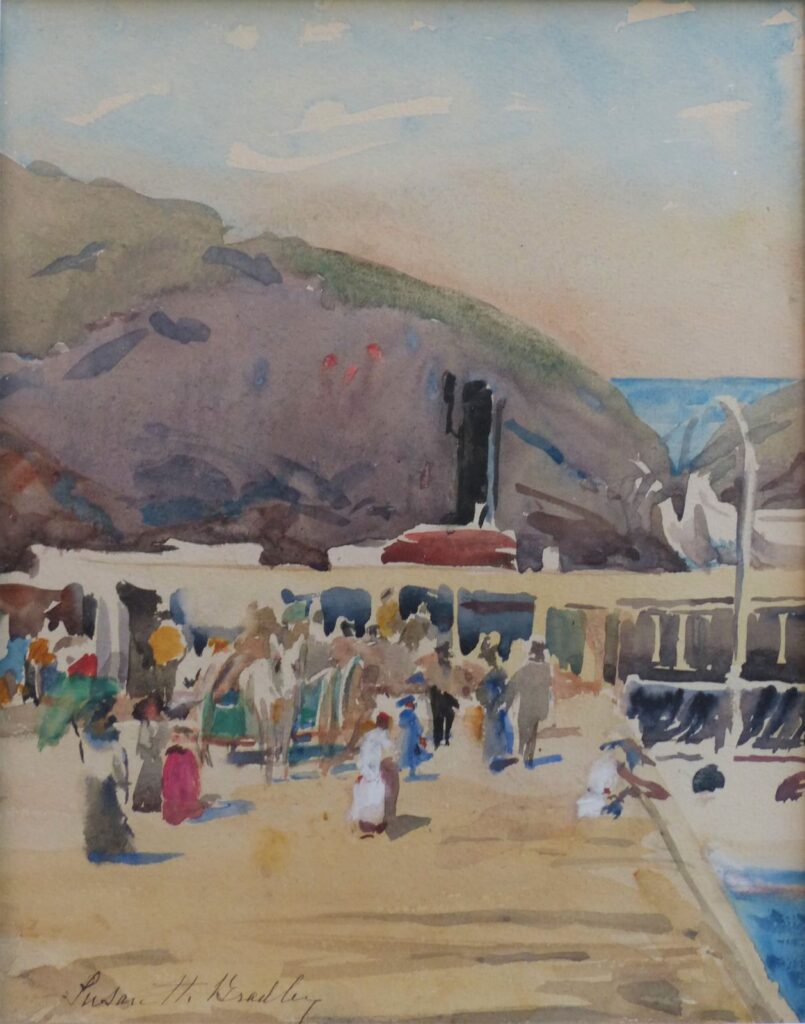

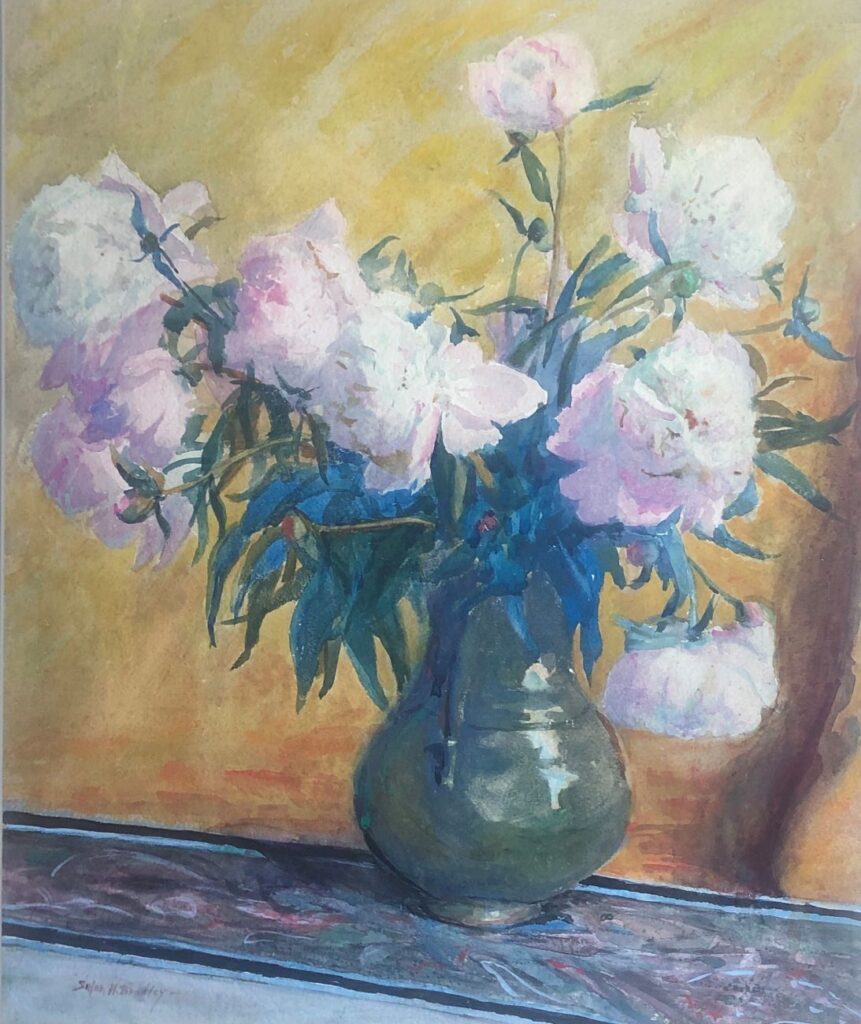

A prolific watercolorist, minister’s wife, and charming socialite, American painter Susan H. Bradley (1851–1929) was good friends with famed artists like John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) and Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942). She frequently exhibited her work alongside other artistic legends including Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), Winslow Homer (1836–1910), and Maurice Prendergast (1858–1924). Not only did she receive critical acclaim as an artist, but she also worked to establish several successful American art organizations that opened doors for women artists and elevated the status of watercolor, her beloved artistic medium. At a time when women were expected to stay behind the scenes, Bradley boldly stepped into the spotlight. How did she do it—and why does her legacy still matter today?

A Family of Distinction and Duty

Susan Hinckley Bradley was born in Boston in 1851 to a family where privilege was balanced by a strong sense of purpose and public service. Her mother, Anne Cutler Hinckley (née Parker), was the granddaughter of U.S. Congressman Jonathan Mason and the daughter of Samuel Parker, Boston’s Attorney General. Her father, Samuel Lyman Hinckley, embodied the 19th-century ideal of a gentleman deeply engaged in the economic and social development of his community, building a multifaceted career based on law, manufacturing, finance, and civic leadership.

Bradley was a vivacious, blue-eyed young woman with a love of fun and adventure. One of five children, she grew up in Boston and spent summers at the family’s spacious home in Northampton, located at 45 Elm Street—now a Smith College dormitory. At age 20, during a trip to visit her brother Robert in Europe—where he was studying painting under French artist Charles Auguste Émile Durand (1837–1917), known as Carolus-Duran—the artist within her awakened.

The trip to Europe would prove transformative in more ways than one. While inspired by the sights and art she encountered, Bradley also suffered a profound personal loss, witnessing her father’s fatal heart attack in Paris. After returning to Boston, she immersed herself in developing her artistic skills.

Overcoming Obstacles

Susan Bradley came of age in a 19th-century world where women endured widespread gender inequality. They were denied equal rights under the law—including the right to vote—and were often portrayed as intellectually and socially inferior to men. Married women, in particular, were considered subordinate to their husbands: they could not own property, sign contracts, or control the money they earned. Opportunities for higher education were scarce for women, as it was widely regarded as unnecessary. This was true in the art world as well. Society expected women to devote themselves to their home and family life, and discouraged personal ambition or the pursuit of a career. Artistic skill served as a feather in the cap of an accomplished upper-class woman, but artistic ambition was considered controversial.

Artistic Training

In 1875, Bradley returned to Europe accompanied by her mother to study under painter Edward Darley Boit (1840-1915), an expatriate with ties to Boston who was living in Italy. Boit was well versed in watercolors and was known for his loose technique. Bradley and Boit forged a close friendship that would span four decades until his death.

After she returned to Boston, Bradley began exhibiting her work with the American Watercolor Society. She was among the few women to take the first life drawing class taught by Frederic Crowninshield (1845–1918) at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School of Drawing and Painting—a notable achievement at a time when most American women were barred from such classes for reasons of modesty. Though mastering the nude figure was essential to artistic credibility, it was paradoxically considered inappropriate for women to study from live models.

Breaking Barriers

By pursuing a career in art and taking classes considered unsuitable for women, Bradley challenged the societal norms of her time. While some women artists succumbed to societal pressure to relinquish their artistic dreams and marry, others chose to remain single to retain their autonomy. Fortunately for Bradley, she found a partner who supported her career as an artist.

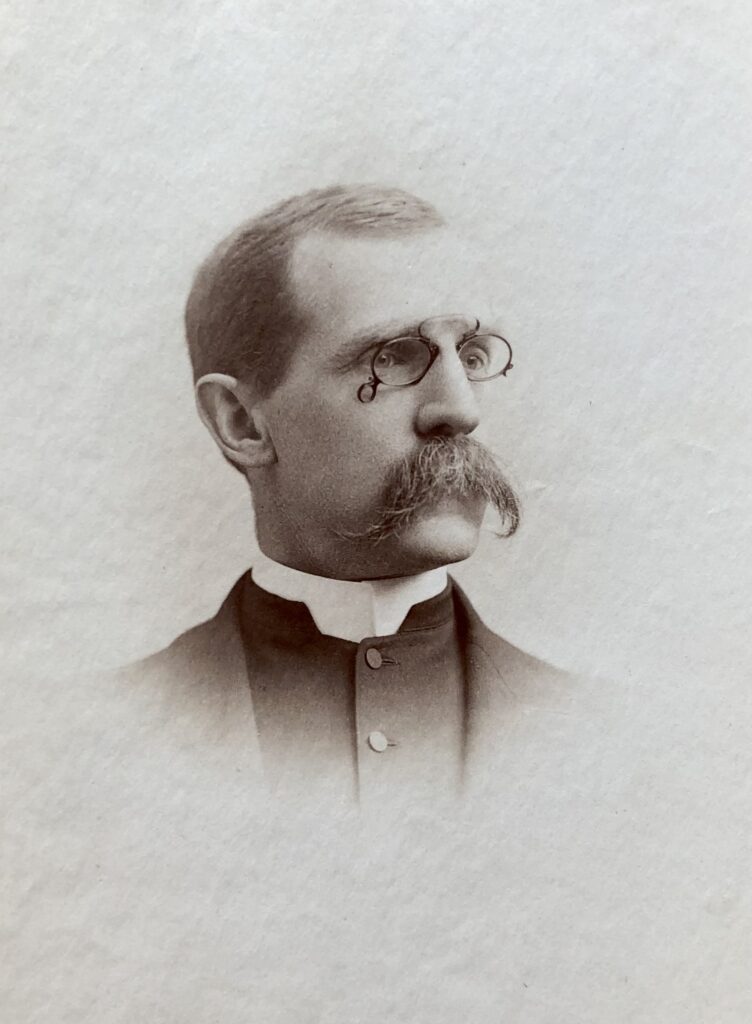

Leverett Bradley was serving as assistant to Phillips Brooks at Trinity Church in Boston when they met. After their wedding in December 1879, Susan and Leverett moved to Gardiner, Maine, where he became rector of Christ Church. During their time there, Susan gave birth to two sons, Leverett and Walter, in quick succession.

Despite this busy period in her life, she made time to paint. In 1883, Bradley began exhibiting her work in the annual exhibitions of the Boston Art Club. Much of her work featured locations in and around Gardiner. In 1884, the family relocated back to Massachusetts when Leverett was hired as the rector of Christ Church in Andover. The couple welcomed a baby girl, Margaret, in 1885.

The Water Color Club of Boston

Ambitious women artists like Bradley faced numerous limitations in Boston, shaped by longstanding gender bias deeply woven into the fabric of society. The city’s popular art clubs, including the Boston Water Color Society, Boston Art Club, and St. Botolph Club, excluded women from their membership, denying them critical exhibition opportunities and the professional networks that their male peers freely enjoyed. Stereotypes propagated by the press frequently dismissed women watercolorists as amateurs, including those who possessed talent, training, and drive. In 1887, in a historic move, Bradley joined forces with 15 other women artists from Boston’s high society to form the Boston Water Color Club. The group included Sarah Wyman Whitman (1842–1904), Sarah Choate Sears (1858–1935), Elizabeth Boott Duveneck (1846–1888), Helen Bigelow Merriman (1844–1933), Ellen Robbins (1828–1905), Fidelia Bridges (1834–1923), and Martha Silsbee (1858–1928).

At first, the club was seen as somewhat of a novelty and reviewed with a patronizing lens. In 1892, a critic in the Boston Evening Transcript reported, “One odd thing about the Watercolor Club is that, although there are no men in it, the inferior sex is called upon to furnish a jury for the exhibitions.” However, over time, through its celebrated annual exhibitions, the Boston Water Color Club won the respect of the art community. In 1898, The Boston Globe observed, “The variety and quality of the exhibition is excellent.” The Boston Water Color Club successfully promoted the work of women watercolorists for nine years, before allowing men to join. It played an instrumental role in increasing the presence and status of women artists in Boston.

At a time when oil painting dominated the art world, the Boston Water Color Club helped elevate watercolor as a serious artistic medium while creating rare opportunities for women artists. Their efforts advanced both the visibility of women in art and the recognition of watercolor’s potential.

Learning from Legends: Bradley and her Teachers

In 1888, shortly after the birth of her fourth child, Ralph, Susan H. Bradley moved to Philadelphia when her husband accepted a new position as rector of St. Luke’s Church. There, she enrolled in classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), eventually becoming a founding member of its alumni fellowship.

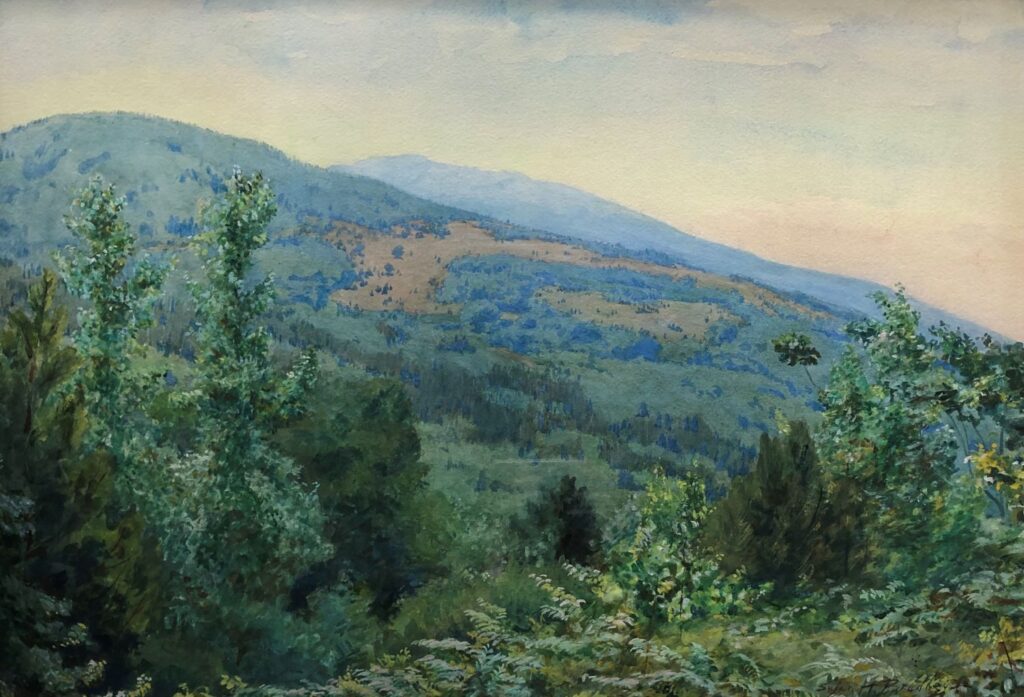

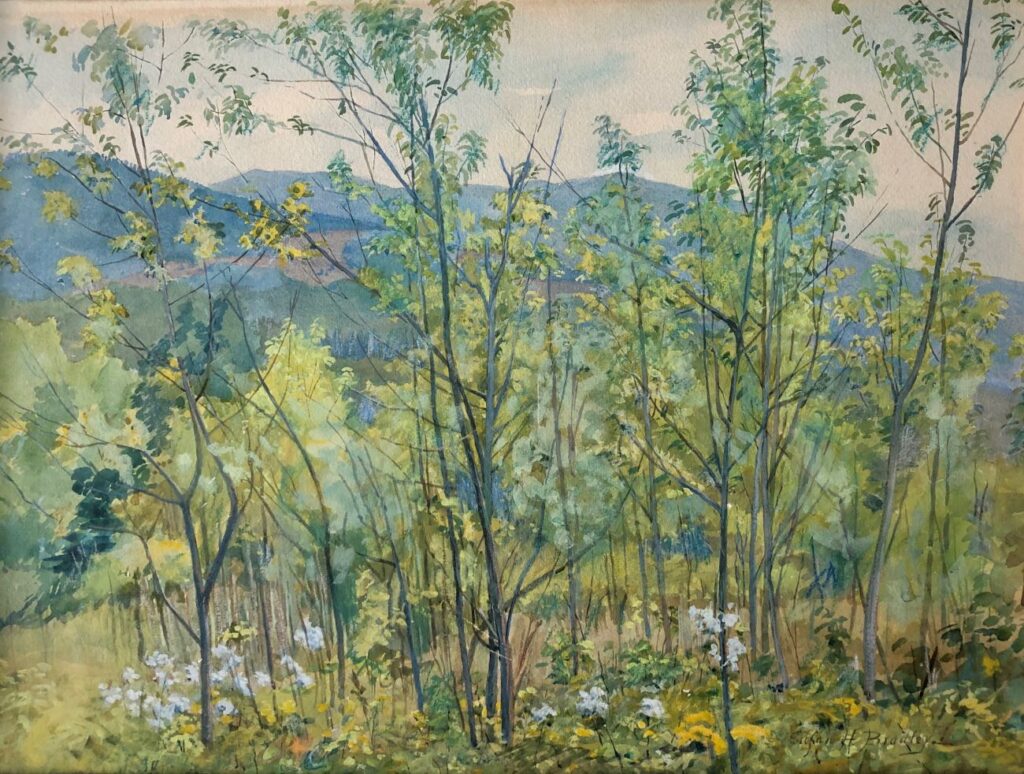

Bradley spent nearly 15 years in Philadelphia, a period marked by artistic growth and expanding professional networks. She and her family frequently escaped the mid-Atlantic heat in favor of the sweeping vistas of New England. In the early 1890s, she spent four summers in Dublin, New Hampshire, studying under Abbott Thayer (1849–1921). She produced numerous works featuring Mt. Monadnock, and one was proudly accepted in the general exhibition (rather than the Women’s Building) at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

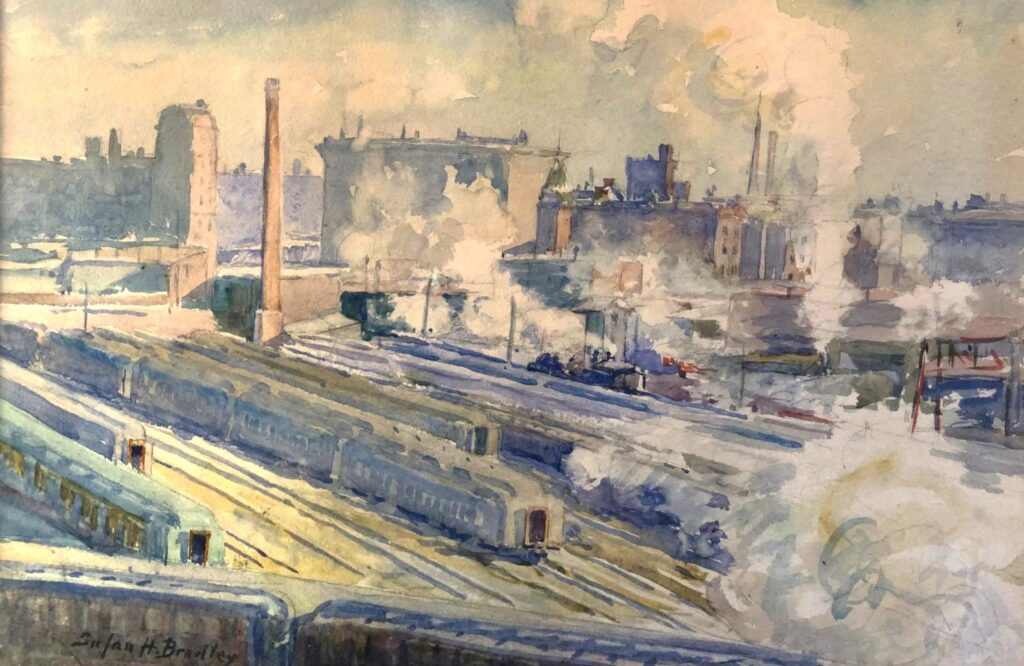

Working to continue her own artistic development, Bradley also sought instruction from other highly respected artists on the East Coast. She studied with William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) in Shinnecock, Long Island; John Twachtman (1853–1902) in New York City; and Frank Weston Benson (1862–1951) in Boston. During this time, she regularly exhibited her work in numerous annual shows in the cities of Philadelphia and Boston as well as with the New York Water Color Club at the Chicago Institute of Art.

The Plastic Club

While advanced art training was becoming more accessible to women in Philadelphia during the 1890s, the city lacked a dedicated space where women artists could gather and exhibit their work. In 1897, Bradley played a key role in founding The Plastic Club, an art organization devoted to supporting women artists across all disciplines—painting, sculpture, illustration, architecture, and education. The name “Plastic” refers to the state of an unfinished work of art. Blanche Dillaye (1851–1931) was elected president, with Bradley and Emily Sartain (1841–1927) as co–vice presidents. Notable members included Margarette Lippincott (1862–1910), Cecilia Beaux, Violet Oakley (1874–1961), Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871–1954), and Jessie Willcox Smith (1863–1935).

With approximately 130 artists listed in its first pamphlet, The Plastic Club’s rented space at 10 South 18th Street quickly became a vibrant hub for exhibitions, lectures, and artistic exchange. Though Bradley’s time with The Plastic Club was brief—cut short when Leverett’s work took them to Europe—her role as a founding member and vice president was pivotal. Her influence helped shape the club’s early years and remains a lasting part of its history.

The Philadelphia Water Color Club

At the turn of the 20th century, PAFA’s crowded annual exhibitions often pushed watercolor works into poorly placed “leftover spaces,” as one critic observed. Frustrated by this, Bradley hosted a meeting in her home in 1900 to establish the Philadelphia Water Color Club. Its leadership drew from institutions like PAFA and the University of Pennsylvania, with Bradley serving on the executive board. Women made up half the founding members—many of them artists who had participated in the early years of The Plastic Club. With honorary members like Sargent, Beaux, and Chase, the club quickly gained prestige. After several successful annual exhibitions, the club was invited in 1904 to partner with PAFA on a new, large-scale annual watercolor exhibition dedicated to works on paper—a monumental achievement for watercolorists and a triumph for Bradley and her peers, who had long championed the medium as a serious art form.

A New Chapter

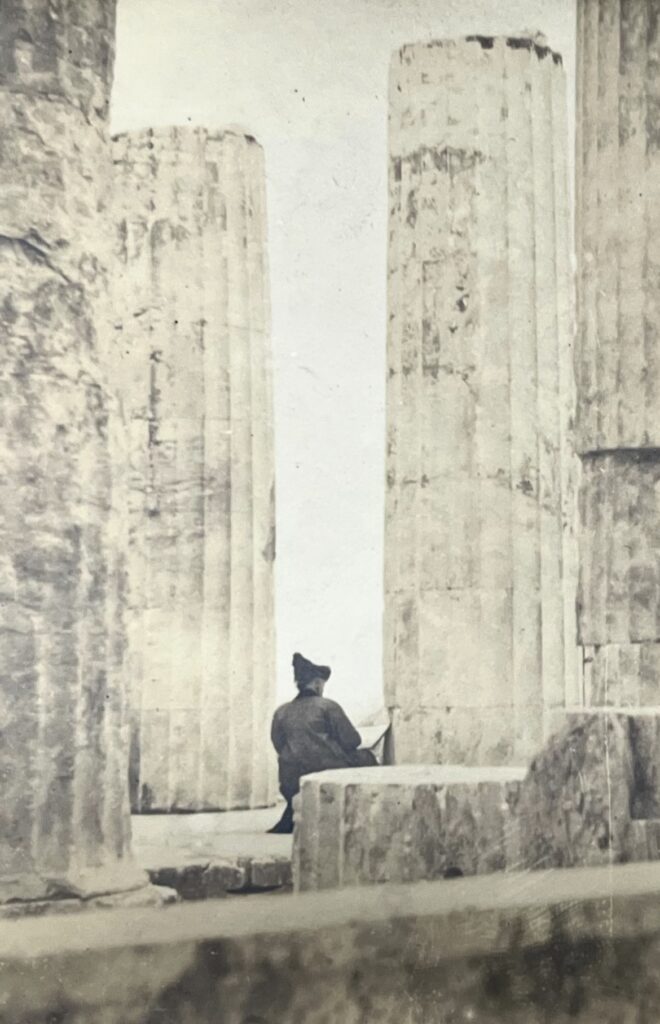

While the Philadelphia Water Color Club flourished, Bradley soon faced a heartbreaking shift in her personal life. Leverett died of heart complications, leaving her a widow at age 51. She moved back to Boston and found that travel offered both a welcome distraction from her grief and on-going inspiration for her art. In the years that followed, she journeyed across Europe and northern Africa. She even visited China and Japan in her seventies. Bradley often spent time with friends and family along the way, and took in the latest exhibitions in the cities she visited.

In addition to her artistic talent, one of Bradley’s greatest gifts was her ability to bring people together. Many of the organizations she supported benefited from Bradley’s strong social skills and wide network of personal contacts. Upon her death at age 78, her close friend Laura Richards wrote to her son Walter, “What a wonderful power of enjoyment she had, what courage, what gaiety! I used to compare her in my mind to a northwest breeze, which came sweeping through the room, bringing freshness and delight with it.”

Lasting Impressions

Susan H. Bradley’s life and work offer a compelling portrait of a woman who refused to be confined by the limits society placed on her gender. She defied societal norms by pursuing a career in art while being married and raising a family. In addition to cultivating her own career, she created organizations that supported and promoted women artists who were struggling to make their mark in the male-dominated art world. She organized groups and participated in exhibitions that helped elevate watercolor from a genteel pastime to a powerful medium for serious artistic expression. She demonstrated a kind of steady, thoughtful leadership that continues to inspire. Her legacy lives on in the lasting beauty of her artwork, the art organizations she helped shape, and the generations of women for whose artistic dreams she helped to forge a path.

Andrea Sluder West holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting and a Bachelor of Arts in Art History from Boston University, as well as a Master of Arts in Teaching in Museum Education from The George Washington University. Passionate about sharing her love of history, she has served as Curator of Education at Gadsby’s Tavern Museum and as Education Coordinator at the USS Constitution Museum. With over 18 years of experience teaching art to both school-aged children and senior adults, her lessons often reference works and themes in art history. As Susan H. Bradley’s direct descendant, West has completed a manuscript chronicling her life and work and is actively seeking a publisher. Follow Andrea on Instagram.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Trackbacks/Pingbacks