by Erika Gaffney, Art Herstory Founder

Under any circumstance, it is a rare treat to encounter the art of American painter Emily Cole (1843–1913). To view it on the very grounds where the artist lived and worked is especially poignant. In this context, Cole’s ceramics and drawings do not merely mirror the beauty of nature. They also inspire the viewer to reflect on nature’s ongoing cycle, and its resilience.

This season, the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in Catskill, New York presents Emily Cole: Ceramics, Flora & Contemporary Responses. Within the historic home and studio, curators Kate Menconeri and Amanda Malmstrom mount the largest exhibition of Cole’s work since the artist’s lifetime. They also place Cole’s creative output in conversation with that of eight contemporary women artists.

Layers of depth

Not just a feast for the eyes, the show is thoughtful and informative. Its goals, which the curators achieve, are admirable and multi-layered.

- Perhaps most obvious, it highlights a significant, but up to now overlooked, historic American artist.

- In the past, cultural commentators have ignored—or dismissed as “craft”—creative output in forms that traditionally only women practiced. In contrast, this show subjects Cole’s flower studies on paper and her ceramic paintings to serious art historical consideration.

- The organizers weave the theme of the “cycle of life” through the exhibition in various and imaginative ways. Thomas Cole’s art addressed human life cycles; Emily’s art addresses the seasonal cycle of plants. The responses of contemporary artists to her work represent generational continuity and renewal. And the flowers visitors walk by on the property are descendants of the plants Emily Cole once painted.

Who was Emily Cole?

One of the five children of Maria and Thomas Cole, Emily Cole grew up in the Hudson River Valley. She lived and worked on the property that is now the Thomas Cole National Historic Site (TCNHS). Cole emulated her famous father in that she forged a career for herself as a professional artist. She painted botanicals on paper (in watercolor) and also on porcelain.

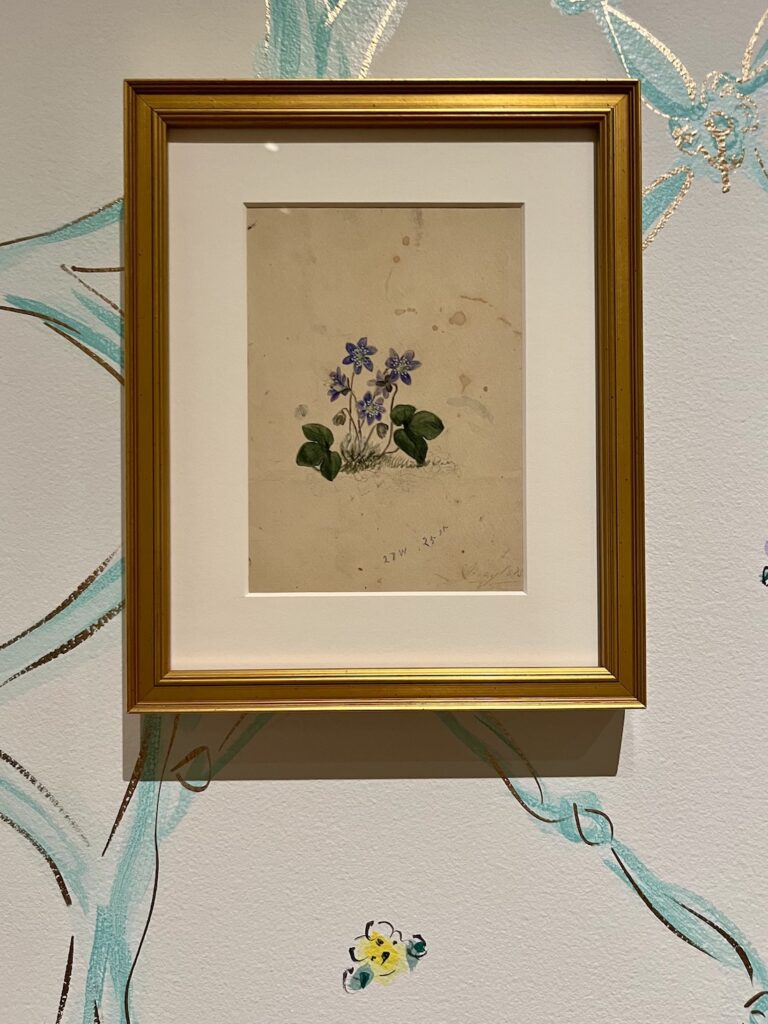

According to curator Amanda Malmstrom, whose research on the artist is extensive, Cole did not display her works on paper. In the book The Art of Emily Cole, Malmstrom notes that at least some of Cole’s watercolors served as preparatory sketches for her ceramic art.

Accomplishments and legacy

Emily Cole did exhibit—to positive reviews—her paintings on porcelain. The New Studio, where some of her work is on view now, is a reconstruction of the building in which she created it. The original structure, demolished in 1973, was one of the sites at which she displayed and sold her work. She produced not only plates, cups, and saucers, but also whole tea sets, including teapots, creamers and sugar bowls. Maintaining at least one kiln on site for her own work, Cole also offered firing services for other artists.

Cole was an active, ambitious and accomplished woman. She traveled internationally and studied at the National Academy of Design. She was a founding member of the New York Society of Ceramic Arts. Upon her death in 1913 at the age of “about 70,” The Columbia Republican published Emily Cole’s obituary. The reporter mentions her “exclusive reputation in this and other states.” The text goes on to read “Miss Cole’s work has found its way to many of the big collections of China [sic] painting in New York and other cities.”

In the New Studio

By the numbers, Emily Cole is the single best-represented artist at the TCNHS. The museum holds about 100 of her drawings and ceramics, which comprises a sixth of its entire collection. Of this cache, about 60 objects appear in the show, including all of the Emily Cole ceramics the TCNHS owns. Also on display are some of the more charismatic of her watercolors, freshly conserved and newly framed.

The New Studio building houses the vast majority of the Emily Cole art in this show. But her work, and therefore her presence, is also sprinkled through the exhibits in the Main House.

The installation in the single room on the lower floor of the New Studio juxtaposes Emily Cole’s art with that of contemporary artist Francesca DiMattio. About 20 of Cole’s watercolor floral studies adorn the wall to visitors’ right as they enter the space. Across the room, DiMattio has painted her own original designs and floral sketches directly on the gallery walls.

DiMattio made paper-mache furniture for the show, basing the designs on elements in Emily’s home. Atop a DiMattio table, the organizers display a full tea service that Emily created. The set is harmonious in that yellow roses adorn every component, but in no two pieces are the flowers painted in exactly the same way.

In this space the visitor also encounters a dynamic installation of DiMattio’s life-size ceramic caryatids.

More contemporary artists respond to Emily Cole

The organizers invited seven other internationally celebrated contemporary artists to engage in a dialogue across time with the nineteenth-century painter. Cole’s work inspired not only DiMattio, but also Ann Agee and Valerie Hegarty, to create new works. And Jacqueline Bishop, Courtney M. Leonard, Jiha Moon, Michelle Sound and Stephanie Syjuco contribute site-responsive installations. The creative responses of these seven artists are on display in the Main House.

On the ground floor

Ann Agee’s room-sized installation of porcelain vases and flower garlands ties directly to Emily’s fascination with flora. Simultaneously, it reflects on the relationships between fine art and craft, and public and private space.

Valerie Hegarty presents two new sculptural installations in the Sitting Room of the artist’s 1815 historic home. These works resonate with the intersection of familial, as well as artistic, commonalities in the experience of the two women.

In the West Parlor, Jacqueline Bishop’s site-responsive installation of ceramics both celebrates the healing power of plants and challenges the colonial narratives often found on fine china tea and dinnerware sets. The artist recently made art news when the Toronto’s Gardiner Museum became the first public collection in Canada to purchase her work (Keeper of All The Secrets, 2023).

On the second floor

Michelle Sound prints cyanotypes of medicinal plants onto elkhide that are assembled with sinew into heads of wooden drums. Sound’s works on display in the hallway at the top of the stairs highlight uses of certain plants and flora as medicine. They illuminate a deeper relationship between plants and animals within the context of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Photographs from Stephanie Syjuco’s Neutral Orchids series engage a critical lens around flowers and their ties to global extraction and movement. The artist focuses on flowers to explore the entrenched history of exoticism and colonialism associated with certain plant and flower species.

Courtney M. Leonard’s art, like that of Emily Cole and Thomas Cole, focuses on our relationship to place, environmental stewardship, and the natural world. Here, her site-responsive installation of ceramic works responds to the rising pollution and water lines of the Hudson River.

Jiha Moon worked with the curators to present a select group of Moon’s jubilant and thought-provoking porcelain teapots, vases, and plates that illuminate global histories of ceramics and bring together Eastern and Western art histories, and popular culture.

Collateral

The shop in the new (since Fall 2023) Visitor Center offers Emily Cole fans the opportunity to learn more about the artist, and to bring home her work. There’s a gorgeous 6-card Art of Emily Cole Botanical Postcard Set. Visitors may also purchase individual postcards, note cards, and reproduction prints of the artist’s botanical studies. The 2024 monograph The Art of Emily Cole is available now. The exhibition catalog Emily Cole: Ceramics, Flora & Contemporary Responses is available as of mid-July 2025. Keep an eye on Art Herstory’s social media channels and newsletter for the publication announcement.

Conclusion

Alongside Emily Cole’s botanical studies in the New Studio hangs Untitled (Cedar Grove), an 1868 oil painting by Charles Herbert Moore. Cedar Grove was the original name of the Cole family’s home. From a distance, the painting portrays the Main House and its garden, which was planted and tended by Harriet Bartow, Emily’s aunt. On the steps sit two women in long gowns and hats—they may be working, conversing, or reading.

Elizabeth Vazquez, a Cole 2024—25 Fellow, kindly pointed out a honey locust tree in the artwork that continues to thrive on the property today. The tree was 40 years old when Moore painted it; now, it is 208. The painting Untitled (Cedar Grove) neatly encapsulates central themes of this beautiful and inspiring show, including the presence and importance of women in the Cole household; the interconnection of nature and art; and the resilience and endurance of the natural world.

Emily Cole: Ceramics, Flora & Contemporary Responses is on at the TCNHS through November 2, 2025.

Erika Gaffney is Founder of Art Herstory. Follow Erika on LinkedIn, Facebook, and/or Bluesky.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Historic Women Artists and Still Life at The Hyde Collection, by Erika Gaffney

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney

Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2025

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely