Guest post by Alessandra Masu, author, journalist and art historian

After the inauguration of the new Sala delle Pittrici (Hall of Women Painters) at Palazzo Braschi in Rome, I spent part of the holidays visiting three pioneering exhibitions on women artists in Modern Age Italy: one in Lombardy; one in the Capital; and another one in the capital of the South: Naples. The result is a small but indicative review of the state of the studies in this field of art history. I therefore share with you just a few thoughts on these shows at the beginning of a new year that I truly hope will be a turning point in Italy’s Art Herstory.

Naples

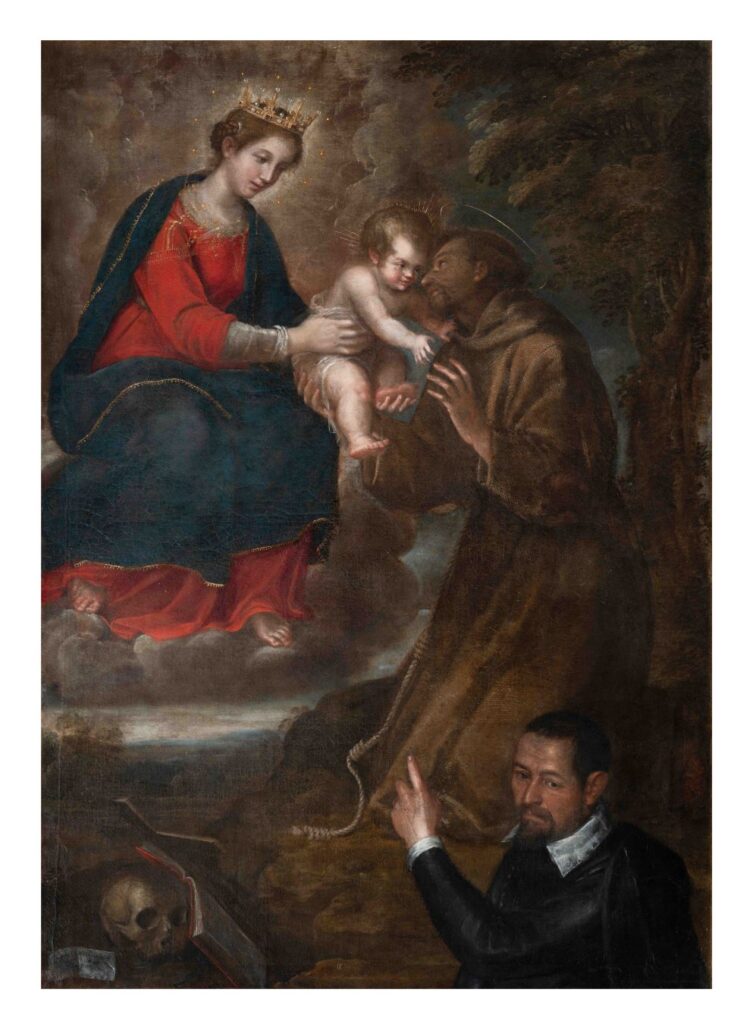

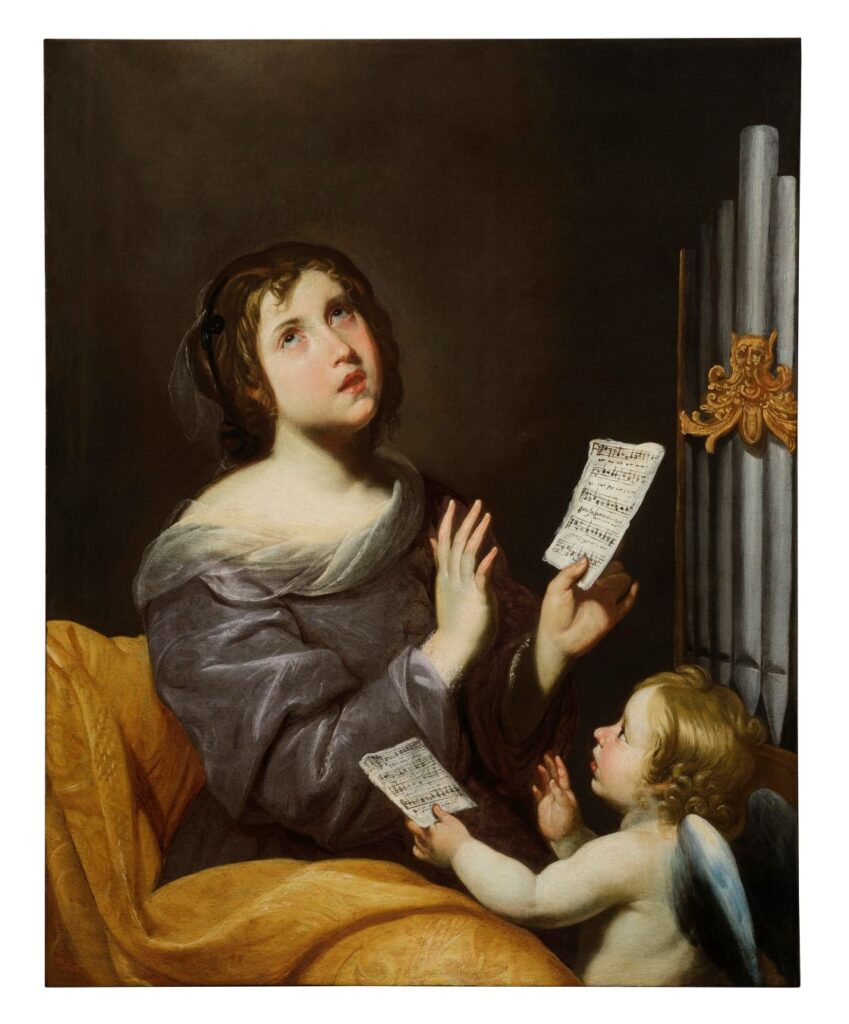

First, I headed South. Destination: Naples. Not the nativity scene market at San Gregorio Armeno (a must, at Christmas, for Neapolitans and tourists), but Women in Spanish Naples: Another Seventeenth Century at the Gallerie d’Italia (through March 22, 2026). This show is the first dedicated entirely to the role of women in 17th-century Neapolitan arts. Arts in the plural, because the exhibition showcases also wax sculptor Caterina De Julianis (Naples, circa 1670–1742), presented alongside the Andalusian Baroque sculptor Luisa Roldán. And a thematic section is dedicated to a pair of eclectic Neapolitan “divas”: the composer, musician and singer Adriana Basile, and the actress, virtuosa and theater impresario Giulia De Caro.

Another peculiarity of the exhibition is its narrative structure, rather than simply chronological and by genre. If the first professional painter active in Rome at the beginning of the seventeenth century—Lavinia Fontana—was not from Rome and reached the peak of her career there, the beginnings of Art Herstory in Naples were more complex, with the arrival of works by Northern Italian artists (Lavinia Fontana, Fede Galizia), and of Artemisia Gentileschi and Giovanna Garzoni in flesh, in 1630. The occasion was the long Neapolitan stopover of the younger sister of the King of Spain Philip IV, the infanta Maria, on her way to marry Ferdinand of Habsburg, king of Hungary and future emperor. Garzoni’s stay in the city was brief, while Artemisia settled in Naples with her daughter, Prudenzia Palmira, and died there during the 1656 plague. Thus, the birth of Art Herstory in Naples had several mothers but only one maestra: Artemisia. She ran a highly successful studio while Caravaggio’s naturalism was in fashion. And in the waning phase of her career, she took on a male collaborator, Onofrio Palumbo, and moved in with another artist’s daughter: Vittoria, daughter of Belisario Corenzio.

The exhibition also highlights lesser-known figures, such as painter and miniaturist Teresa Del Po, and the first professional and successful Neapolitan painter by birth and education: Diana Di Rosa. Unfortunately, the reconstruction of her personality in the show is a puzzle of the influences of the men in her life (father, stepfather, master, brother, husband), rather than being based on the research and identification of the unfortunately few documented works. Personally, I would have also appreciated more space both in the exhibition and—at least—in the catalogue for a broader and more in-depth survey on the history of women in Naples, only sketched in the introductory essay by Elisa Novi Chavarria.

Mantua

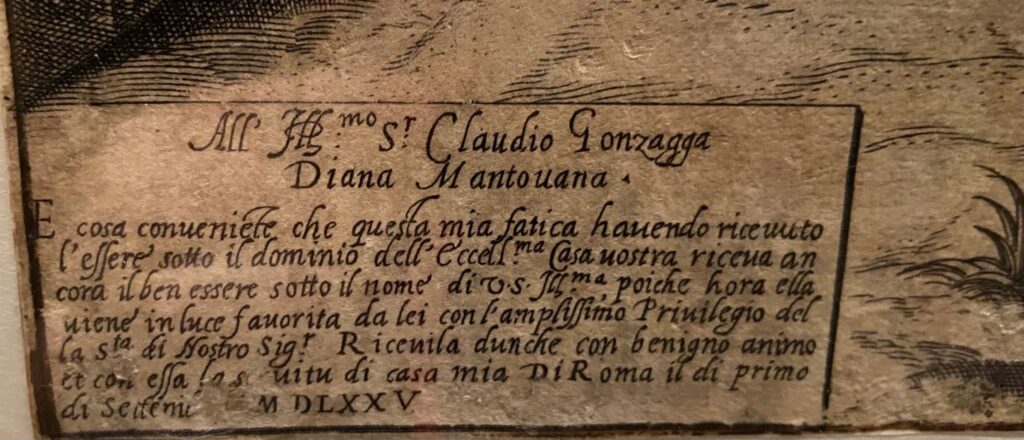

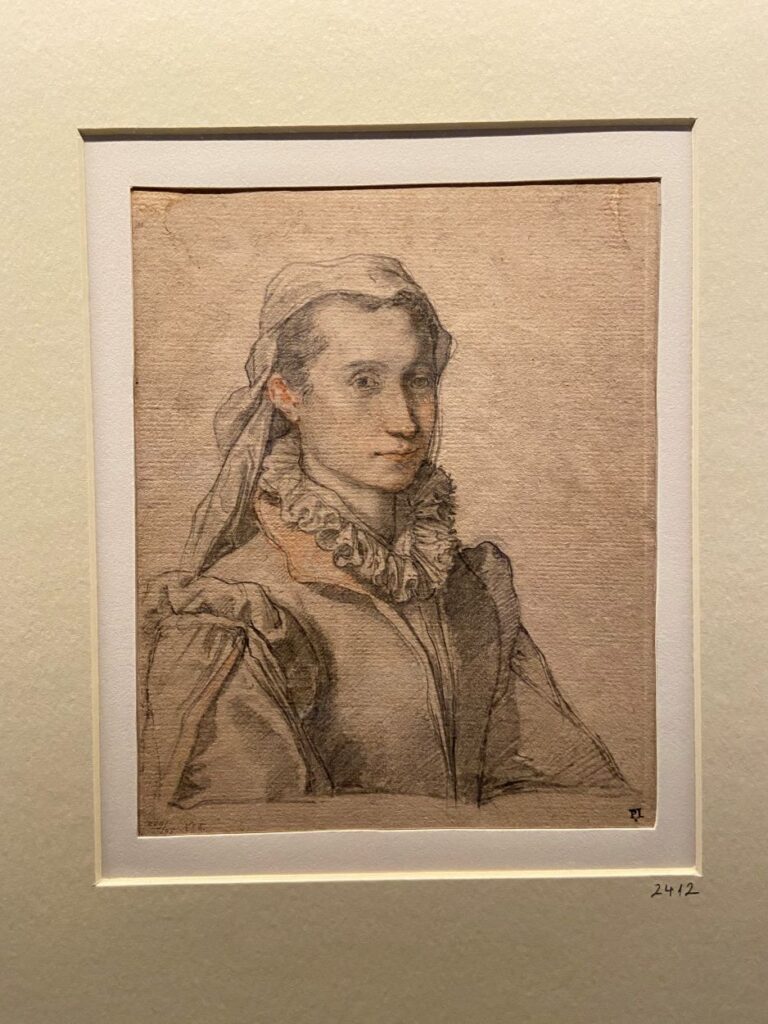

In the early days of the New Year I ventured from Milan to Mantua, defying the seasonal fogs in the Padana Plains and the freezing cold Palazzo Ducale where the exhibition Diana Scultori, “intagliatrice rara” Un’artista tra Mantova e Roma nel Cinquecento was hosted (closed on January 11, 2026). The exhibition was another big first: the first monographic show of the first woman to earn a special privilege to sign, print and market her engravings, in 1575. It was granted to her by Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni, patron of Lavinia Fontana, who portrayed him and members of his family. The license made her the first woman in history to claim exclusive creative ownership of her work.

Born and educated in Mantua, Diana was not yet twenty years old in 1566, when Vasari met her during a visit to Mantua, one of the most splendid courts of the Italian Renaissance. In fact Vasari mentioned her in the second edition of his Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects (1550 and 1568), appreciating her technical prowess, as well as her grace. Sometime in the late 1560s Diana met the architect Francesco Capriani, known as Francesco da Volterra, active in Mantua for Cesare Gonzaga. By 1575 they were married and she joined him in Rome, to become a distinguished member of the city’s cultural and artistic scene. In 1575 Diana obtained the papal privilege which allowed her to transpose into engravings her husband’s drawings, and those of other artists of their circle, with her signature, and distribute the prints for the next ten years on an exclusive basis.

Their only documented child, Giovanni Battista, was born in Rome in 1577. In 1580 Diana was the first woman to be admitted to the Accademia (in reality it was more of a “confraternity”) dei Virtuosi del Pantheon. When her husband died in 1594, Diana stayed in the same house-atelier with her son, her elderly mother Osanna and sister Ippolita. In 1596 she married again, to another architect: the Roman Giulio Pelosi. Diana died in 1612.

The exhibition comprehensively and enjoyably covered Scultori’s entire life and artistic production, between Mantua and Rome. So I was shocked by the lack of a printed catalog. To commemorate an historically important exhibition, and to create a point of reference for future studies, the organizers produced only a digital brochure (downloadable from the Palazzo Ducale website)?! Moreover, given that in 2024 the exhibition on Diana’s father—the sculptor, painter and engraver Giovan Battista Scultori—in the same venue, was obviously accompanied by a proper catalog. I just hope a way is found to fix this. As soon as possible.

Back to Rome

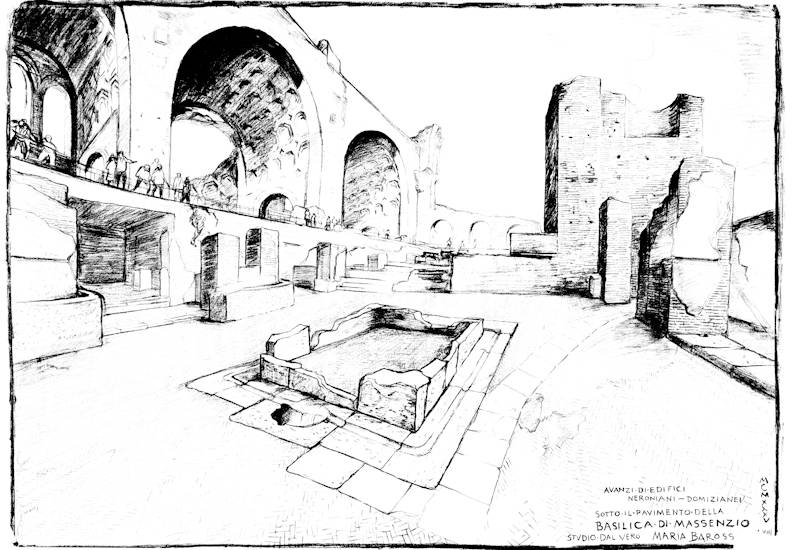

In one of the city’s most fascinating museums, the Centrale Montemartini, a former power plant turned into Rome’s civic archeological museum, has been extended until February 22, 2026 the exhibition of an authentic discovery: the archeo-painter Maria Barosso (Turin, 1879–Rome, 1960). Maria Barosso, artista e archeologa nella Roma in trasformazione is the first monographic exhibition dedicated to the first female official at the Directorate General of Antiquities and Fine Arts in Rome, where she was employed in 1905. She had attended the Accademia Albertina in Turin and had some teaching experience. Working with Giacomo Boni, then director of the Roman Forum excavations, she embarked on a professional journey that led her to witness the capital’s major urban transformations for half a century.

Through accurate graphic reproductions and lively watercolors, she witnessed the most important demolitions and excavation sites of the Superintendency of Rome and Lazio, embodying a unique role of archeologist-artist. Her specific talent is a combination of philological rigor and aesthetic sensitivity in documenting the historical and archaeological heritage.

Of the 137 works on display, including approximately 100 prints, drawings, watercolors, and paintings by Maria Barosso, a significant number come from the storages of the Capitoline Superintendency, and in particular from the Museum of Rome at Palazzo Braschi. The show is very well documented in a beautiful catalogue published by De Luca Editori d’Arte.

Author, journalist and art historian Alessandra Masu loves to unearth the stories of overlooked women. She collects art created by women from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century. Alessandra’s writing has appeared in many places in print including D, la Repubblica’s weekly style magazine. As an art historian, Alessandra has contributed to several exhibitions and art publications. She is the author of the historical novel Lena, che è donna di Caravaggio. In 2025 Ginevra Bentivoglio Editoria published a second edition of her book Perchè io non voglio star più a questa vita. La voce di Beatrice Cenci dai documenti conservati negli archivi romani (originally published in 2020). In 2016 Alessandra, in collaboration with art historians Consuelo Lollobrigida and Beatrice De Ruggieri, founded the cultural association Artemisia Gentileschi, which is based in Rome. On March 8, International Women’s Day 2022, the association launched the Artemisie Museum project. It is the first virtual museum-database of women in the arts.

More posts by Alessandra Masu

A Home for Women Artists in Rome

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day”

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome

More Art Herstory posts about exhibitions

Museum exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2026

Historic Women Artists and Still Life at The Hyde Collection, by Erika Gaffney

Rachel Ruysch: The Art of Nature, by Stephanie Dickey

Dutch and Flemish Women Artists—A Major Exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, by Erika Gaffney

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney