Historic and contemporary female landscape artists in conversation

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site (TCNHS) in Catskill, New York is an exhibition in two parts. Three curators—Nancy Siegel, Kate Menconeri and Amanda Malmstrom—collaborate to present a transhistoric survey of how American women artists have engaged, and continue to engage, with land.

Celebrating Susie Barstow, and other women of the Hudson River School

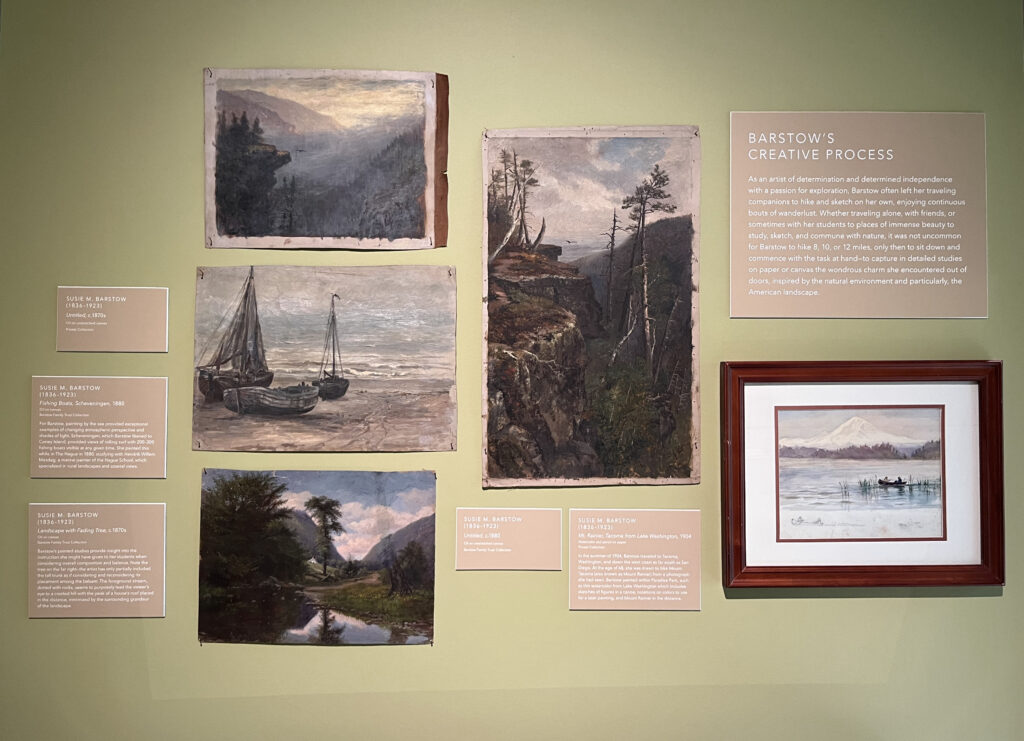

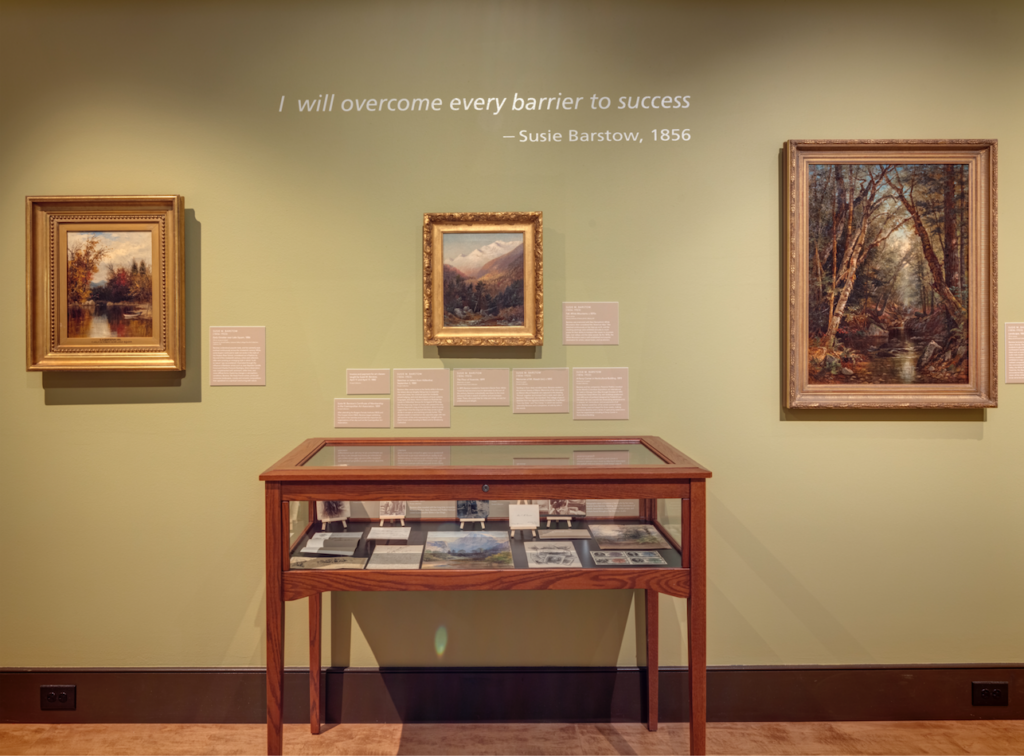

The historic portion of the show, Susie Barstow and Her Circle, is housed in the New Studio building. This segment recognizes the contributions of women painters of the Hudson River School, with a special focus on nineteenth-century American landscape artist Susie Barstow. According to Nancy Siegel’s Art Herstory guest post about this artist, though Barstow maintained a presence in New York City via her Brooklyn studio, she was a lover of the outdoors and an inveterate hiker. Barstow frequented the Catskills, the Adirondacks, the White Mountains, and the lakes and mountains of Maine for inspiration. She made multiple excursions abroad with and without her partner, Florence Nightingale Thallon, a fellow artist with whom she frequently lived and traveled for nearly two decades.

In the TCNHS exhibition, about a dozen of Barstow’s framed landscape oil paintings adorn two of the walls. There are also display cases that present objects of material culture, including Susie’s paintbox.

Also on view are tickets she saved from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, letters, small drawings, a receipt to one of her students for art lessons, and the artist’s calling card.

On the remaining walls within the New Studio segment of the exhibition, visitors find paintings by other women artists of the Hudson River School. These painters include Laura Woodward, Eliza Pratt Greatorex, Julie Hart Beers, Charlotte Buell Coman, Mary Josephine Walters, and Fidelia Bridges.

Public vs. private collections

Though some of the paintings in this room are on loan from public institutions—among them the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, and the Albany Institute of Art and History—most are from private collections. Dismayingly few public collections seem to own works by these artists, so perhaps this is unsurprising. But I was slightly surprised and pleased to notice that the placards identify many of the owners by name.

While both Fidelia Bridges paintings in this exhibit are from private collections, this artist is an exception to the generalization above. More than 30 US museums hold at least one of her works, whether an oil painting, a watercolor, or a chromolithograph. Presumably when the show moves to the New Britain Museum of American Art, and then the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, these institutions will add some of their own Bridges holdings to the historic art segment. (One of the Woodson Art Museum’s current exhibitions is Fidelia Bridges: The Artful Sketch.)

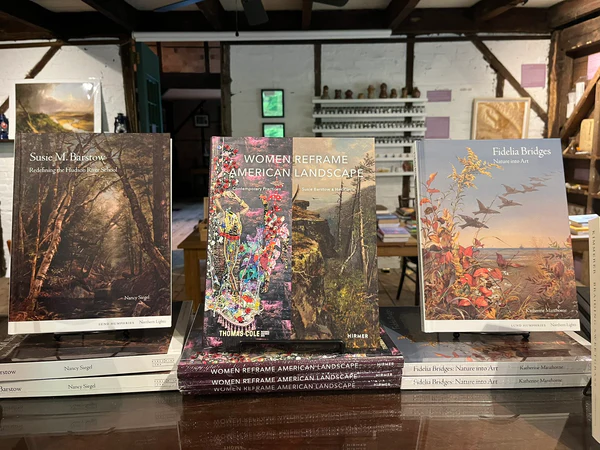

A special anniversary: Barstow and Bridges, one hundred years on

This year marks a significant anniversary for Bridges as well as for Barstow. It is exactly one century since each woman died in 1923. There is a beautifully illustrated, accessibly written new book about each artist to commemorate the anniversary. A copy of each is available in the New Studio for visitors to browse: Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel; and Fidelia Bridges: Nature into Art, by Katherine Manthorne. Other books on women artists by Manthorne include Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex and Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900.

Interlude: Properties and practicalities

Outdoors

Contemporary Practices, the complementary segment of this exhibition, is located in the Main House on the TCNHS grounds. Before moving on to this portion of the show, let me explain the layout of the site. The museum sits on the property where Thomas Cole, the English-born founder of the Hudson River School, lived and worked. But notice I don’t write, “on the property once owned by Thomas Cole.” Interestingly, during his lifetime the owners were first his wife’s uncle, and later his sister-in-law. Eventually, Cole’s wife Maria became the owner, but that was after his death.

There are currently three structures on the grounds. These include the New Studio, which I mention above; it is a reproduction, built in 2015. The original building was torn down in 1973. The ground floor is an exhibit space; upstairs is the museum’s mechanical room. The Old Studio, restored in 2004, is the back room of a former storehouse for crop harvests. It now contains the Visitor’s Center and museum shop, as well as some supplemental exhibit space. (When the new purpose-built Visitor’s Center is complete, this historic building will become a space for meetings and workshops.) And the largest building is the three-story Main House.

Indoors

The temporary display of contemporary artwork in the Main House intermixes with the permanent display. Among the objects are paintings by Thomas Cole, and furnishings and equipment that he and his household used. The focus on the household, as well as the artist, is deliberate, and important. The museum team has set itself an explicit mission to conduct research on all historic figures associated with the site. As I will touch on again later in this review, everyone who contributed to the property’s upkeep and functioning matters, whether their names are known to us or not.

Throughout the house, digital technology discretely complements the historical appointments. There are artworks projected onto screens, informational videos, supplemental texts one can scroll digitally, links to audio commentary by the exhibition’s curators, and QR codes linking to further information online. Less high tech, but also very helpful in certain weather, are the large umbrellas that circulate among the three buildings.

How do women artists engage with land today?

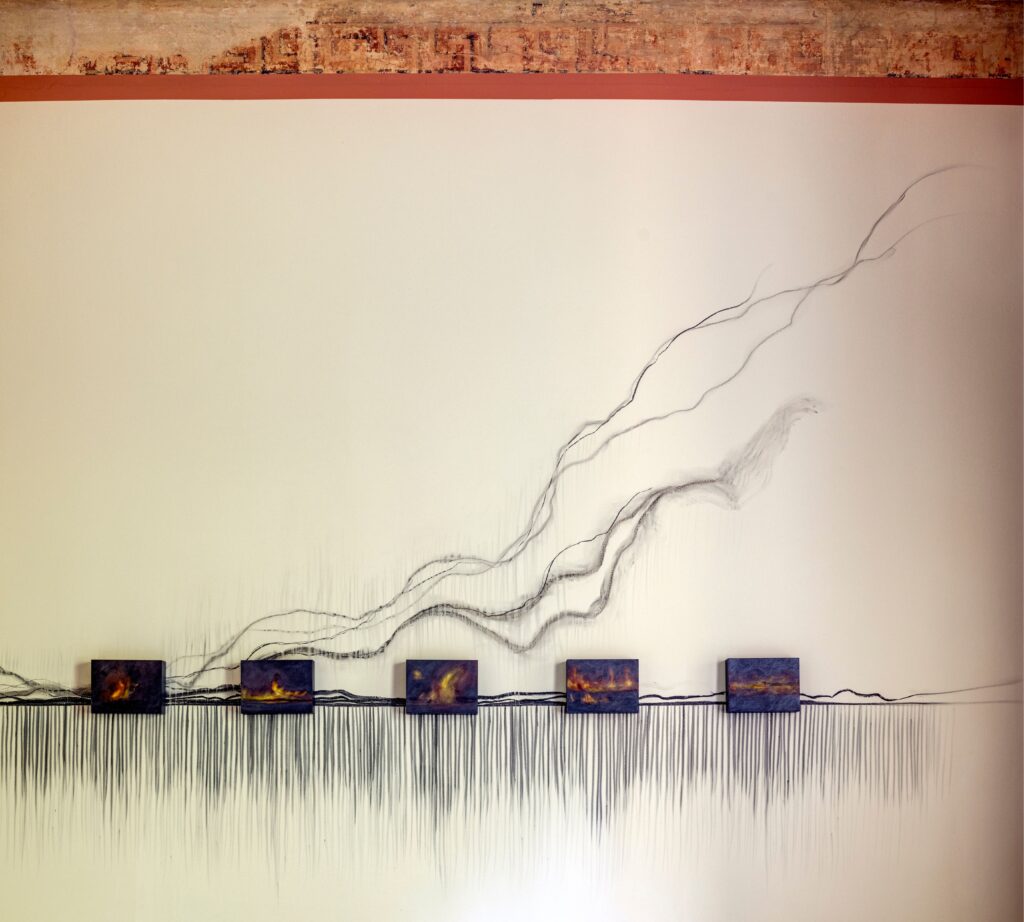

Contemporary Practices features living artists whose work touches—albeit in very different ways—on our relationship with the land. Teresita Fernández‘s thinking about landscape informs the entire enterprise; the artist contributes an essay to the exhibition catalog. I particularly admired her site-specific installation in one of the ground floor rooms, which incorporates only materials found in nature. (And I admit I am quite curious as to how/whether a site-specific installation transfers to the other venues for this show.)

On the same floor, a multi-media (and multi-layered) work by Ebony G. Patterson takes up a considerable portion of one wall. On the stair landing is a characteristically humorous-yet-incisive poster from the Guerrilla Girls, specially composed for this exhibition. Upstairs, visitors will view paintings by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and some of her beadwork, on display here for the first time.

There is also book art by Anna Plesset; sculpture by Jean Shin; a set of “seasons” photographic self-portraits by Wendy Red Star; and a wall-size photograph by Tanya Marcuse of carefully staged objects. A viewer might easily mistake the latter for a mural. Other artists with art on display in the house or in the Old Studio in the Visitor’s Center are Marie Lorenz, Mary Mattingly, Cecilia Vicuña, Kay WalkingStick, and Saya Woolfalk.

The Cole women, and other important members of the household

And for visitors who thought they had left historic women artists behind in the New Studio, there is a pleasant surprise. The Main House display includes oil paintings by Cole’s sister Sarah, and watercolors and decorated china by his daughter Emily! According to the TCNHS website, Emily Cole lived on the property her whole life and made a living selling her art. She was the focus of the 2019 exhibition The Art of Emily Cole. The TCNHS owns some 60 of Emily’s watercolor illustrations; her artistic output constitutes approximately one sixth of the collection. Personal aside: I was gleeful to purchase the Art of Emily Cole Botanical Postcard Set, which I have long coveted.

As I mention above, the permanent display in the House does not focus solely on Thomas Cole. It recognizes not only his sister, painter Sarah Cole, and his artist-daughter Emily, but also Maria Bartow, his wife and indispensable advisor. And importantly, the text around the house acknowledges the work of people—at least some of whom were enslaved, prior to Thomas Cole’s time at the house—who cooked, cleaned, sewed, and provided other essential services. A very small basement bedroom attests that not everyone who lived in the house was as privileged as those who occupied the upstairs bedrooms. It is an ambition of the museum team eventually to restore the house’s original kitchen in a way that honors all persons connected with it.

More venues in which to see, or read about, this exhibition

Women Reframe American Landscape is on at the TCNHS through October 29, 2023. Then, the New Britain Museum of American Art hosts the show from November 18, 2023 to March 31, 2024. And it will be on view at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum from May 4 to August 25, 2024.

Read more reviews of this exhibition from Forbes.com, The Times Union, Cultured Mag, DailyArt Magazine, and Artnet News. The exhibition catalog is available from the TCNHS and Hirmer; it is also available in North America from the University of Chicago Press.

Erika Gaffney is Founder of Art Herstory. Follow Erika on LinkedIn, Facebook, and/or Bluesky,

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

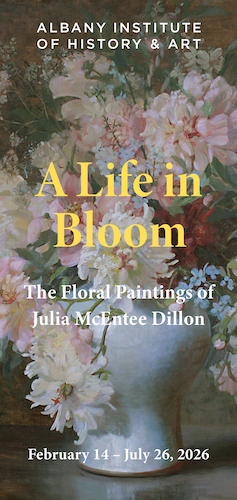

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Science, Nature, and Music in the Art of Alma Thomas, by Erika Gaffney

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely