Guest post by Rowena Loverance, independent scholar, London

Sylvia Shaw Judson was a professional sculptor who specialized in depicting children and animals. In midlife, however, she became a Quaker, and her career took a dramatic turn.

Quaker women artists: the context

Readers of the Art Herstory blog have already been alerted to the existence of Quaker women artists, through Erika Piola’s post on African American educator, civil rights activist, essayist, and artist Sarah Mapps Douglass (1806–1882). However, Douglass’ known extant work comprises just eight drawings. Perhaps being a Quaker woman artist, let alone a Black Quaker woman artist, has always been a difficult business.

Quakerism, an offshoot of seventeenth-century Puritanism, originated in northern England in the 1650s and spread rapidly in North America. From the start it had a troubled relationship with the arts, seeing them as vanity and distraction. The only voice recorded as speaking out in favor of a more creative approach was that of Margaret Fell, one of the few women among the founding group. But her words of caution, “We must be all in one dress and one colour: this is a silly poor Gospel,” went largely unheeded. Quakers continued to refrain from decorating their meeting houses or commissioning family portraits for their homes. In the absence of this basic patronage from their community, even if a Quaker artist overcame his or her own moral scruples about the making of art, it was an uphill struggle to make a living.

A privileged life

Sylvia Shaw Judson (1897–1978) did not start out as a Quaker. Born in Chicago, the second of three daughters of architect Howard Van Doren Shaw and Frances Wells Shaw, a poet and playwright, she soon identified her future career, writing in 1914 in her school magazine that she wanted to be a sculptor and that “my specialty is going to be garden sculptures.” Given her privileged background, this was an eminently achievable ambition. The grounds of her family home at Ragdale, Lake Forest, were adorned with prime examples of European, Asian and American sculpture, while at Chicago’s Art Institute, sculptor Lorado Taft was renowned for helping to advance the status of his female students. And even before starting her formal studies, Sylvia had the inspiration of a summer’s internship with one of the foremost female sculptors of the day, Anna Hyatt Huntington. This was at the very time when Hyatt was in the process of installing the first public monument by a woman in New York—her massive equestrian statue of Joan of Arc on Riverside Drive. So Sylvia was encouraged from the start to aim high.

At the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, from 1915 to 1918, she studied with the new head of department, Czech-American sculptor Albin Polášek. In 1920 she spent a year in Paris at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, taught by Antoine Bourdelle, who had worked for many years with Rodin. The Academy, in contrast to the stricter École des Beaux-Arts, prided itself on its creative freedom: its sculpture students in the 1920s would include Alberto Giacometti, Alexander Calder and Josefina de Vasconcellos. Sylvia prospered there, exhibiting two pieces at the Paris Spring Salon in 1921.

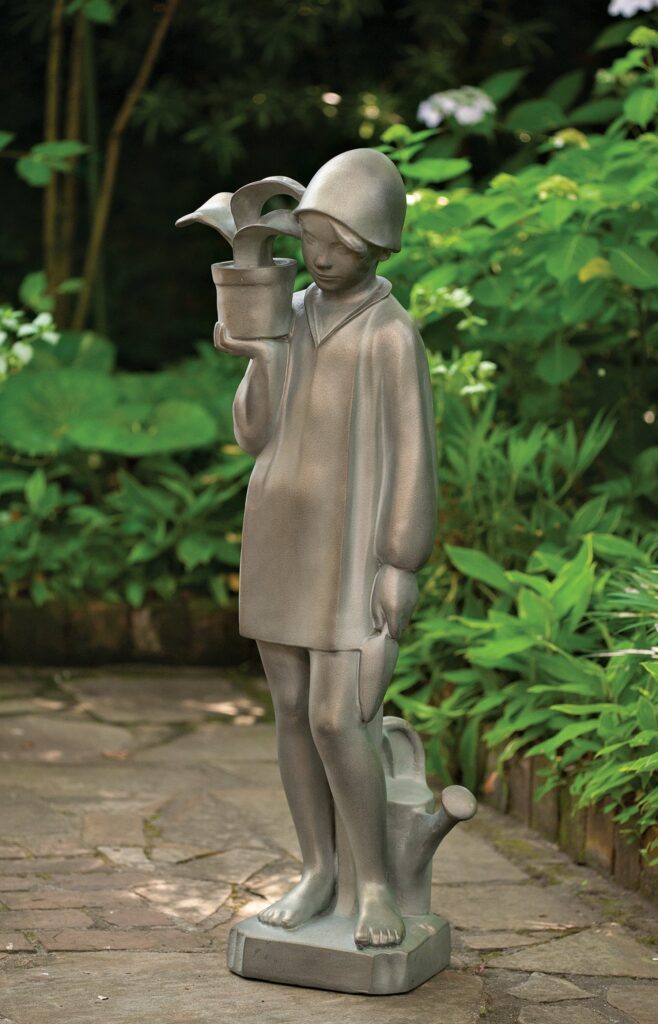

Little Gardener and Bird Girl

On her return to the US, Sylvia married Clay Judson, a law graduate from Chicago, and set up a studio in a basement laundry room below their apartment. Her early work drew on her life as a young mother: she used her children as models for several of her works. Little Gardener (bronze, 1929), in which her daughter Alice is depicted barefoot, holding a trowel and a potted plant, won her the Logan Prize from the Art Institute in 1929. She was the only woman sculptor to receive this award in its 70-year history.

Little Gardener was to bring her added fame later in life when it was acquired for the redesigned Jacqueline Kennedy Garden at the White House in 1964; it has remained there ever since. This was as nothing, however, to the posthumous fame she was to acquire through a similar work made a few years later in 1936. Commissioned by the Ryerson family in Chicago, and originally entitled Fountain Figure, it depicts a young girl, plainly dressed, holding two bowls in either hand, in a gesture which could be interpreted either as balancing or weighing. Four castings were made, one of which stood anonymously in Bonaventure Cemetery, Savannah, Georgia, until an evocative photograph of it taken at dusk by Jack Leigh (Midnight, Bonaventure Cemetery, 1993) was featured on the cover of John Berendt’s bestseller Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994) and on the poster of the film adaptation (1997), directed by Clint Eastwood. Popularly known as Bird Girl, this is now far and away Sylvia Shaw Judson’s best-known work.

Quaker convincement

Little is known of Sylvia’s early religious life. The experience of the Second World War must have provoked doubts about the rightness of war in both her and her husband. Clay Judson came from a military family, but prior to the outbreak of war served on the America First Committee, which was dedicated to keeping the United States out of the war. It may have been these pacifist instincts, which Sylvia clearly shared, which drew her to the Religious Society of Friends. She became a Quaker in 1949. She soon established regular Quaker meetings for worship at Ragdale, making available the space she had been using as a studio. The group grew in size and in 1952 Lake Forest was formally established as a Quaker Meeting.

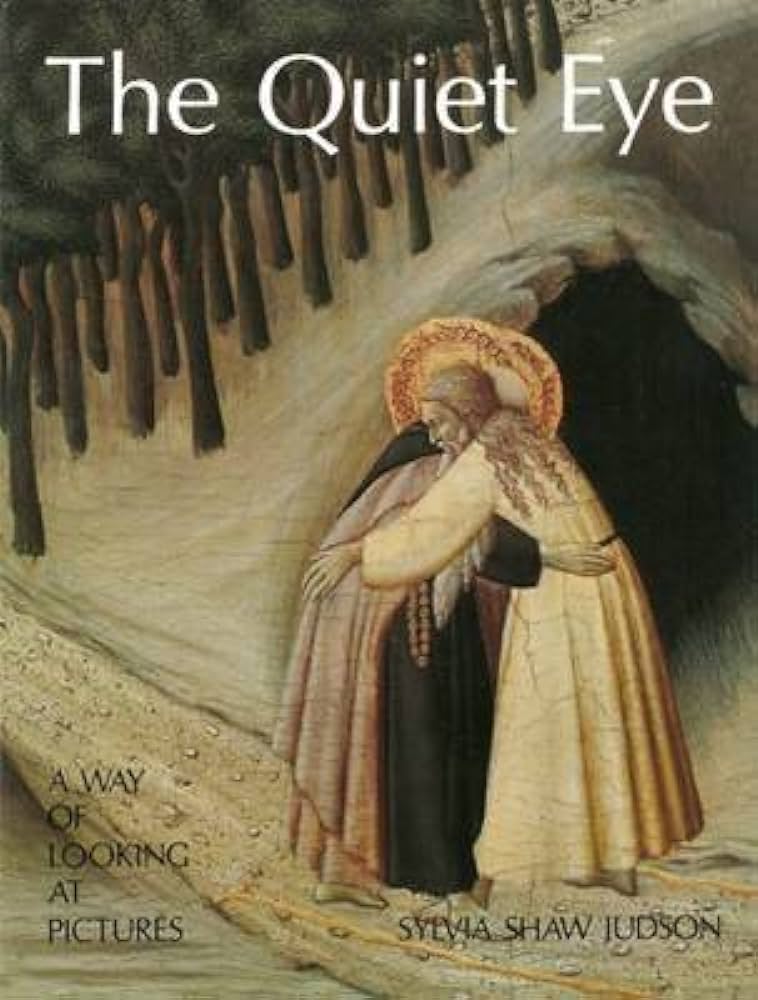

It seems that it was the tension between her new faith and her identity as an artist which prompted Sylvia Shaw Judson to publish her first book, The Quiet Eye: A Way of Looking at Pictures, in 1954. This unassuming little book features 33 artworks by artists from the seventh century to the modern day which Sylvia believed displayed Quaker ideals. In making her selection, she emphasized the term “divine ordinariness,” defined as the “delicate balance between the outward and the inward, with freshness and a serene wholeness and respect for all simple first-rate things, which are for all times and all people.”

Ironically, however, the sculpture she was about to make represented the very opposite of ordinariness.

Mary Dyer, Quaker martyr

In the very early days of Quakerism in North America, an English settler in Boston, Mary Dyer, became one of its first preachers. She had already reached her own insight that God speaks to people directly, not through priests, the liturgy or the Bible. Visiting England in 1652, she discovered that this insight was the kernel of the new Quaker movement. By 1657, however, when she returned to Boston, the Puritan authorities had banned Quakers from entering the colony. Determined to preach her new faith, Mary defied the ban again and again, even when it carried the death penalty. On one occasion she was reprieved only minutes from execution. On her fourth return, however, there was to be no reprieve, and Mary Dyer was hanged on Boston Common on 1 June 1660.

As the tercentenary of the event approached, the state of Massachusetts launched an art competition to design a statue of Mary Dyer. Sylvia Shaw Judson was awarded the commission in 1957. She was not previously known as a portrait sculptor but this did not greatly matter, since no contemporary image of Mary Dyer exists. Nor was there any tradition of Quaker three-dimensional portraiture for Sylvia to draw on, beyond some generic images of William Penn, founding father of Philadelphia.

Courage, compassion and peace

Sylvia chose to depict Mary Dyer seated on a meeting house bench, her head bowed and her hands folded in her lap. She wears Quaker plain dress, her hair is tucked up under her cap and her dress wraps across her chest and almost covers her feet. The sculpture conveys its power through its sheer simplicity: it is an image of meekness which somehow manages to convey resolve. Sylvia has given the bronze a weathered feel which adds to the effect of endurance under pressure. She wanted the figure to depict “courage, compassion and peace. I also wanted her quite simply to exist—solitary and exposed, as though the only safety was within.” Mary Dyer looks down on the viewer from a high plinth, on which are inscribed words which she wrote to the court after her 1659 reprieve, “My life not availeth me in comparison to the liberty of truth.”

At seven feet high, Monument to Mary Dyer was the largest sculpture Sylvia Shaw Judson ever made. It took her two years to sculpt it, and supervise its casting and installation. Most of her works were cast by the Roman Bronze Company of Corona, Long Island, New York but she had Monument to Mary Dyer cast at the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry in Florence, Italy.

In addition to the statue in Boston, two other castings were made. The second was housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until 1975 when it was set up at the Friends Center in Philadelphia. The third, a shortened version, was placed in front of the Stout Meeting House at Earlham College, (Richmond, Indiana) in 1962.

After Mary Dyer

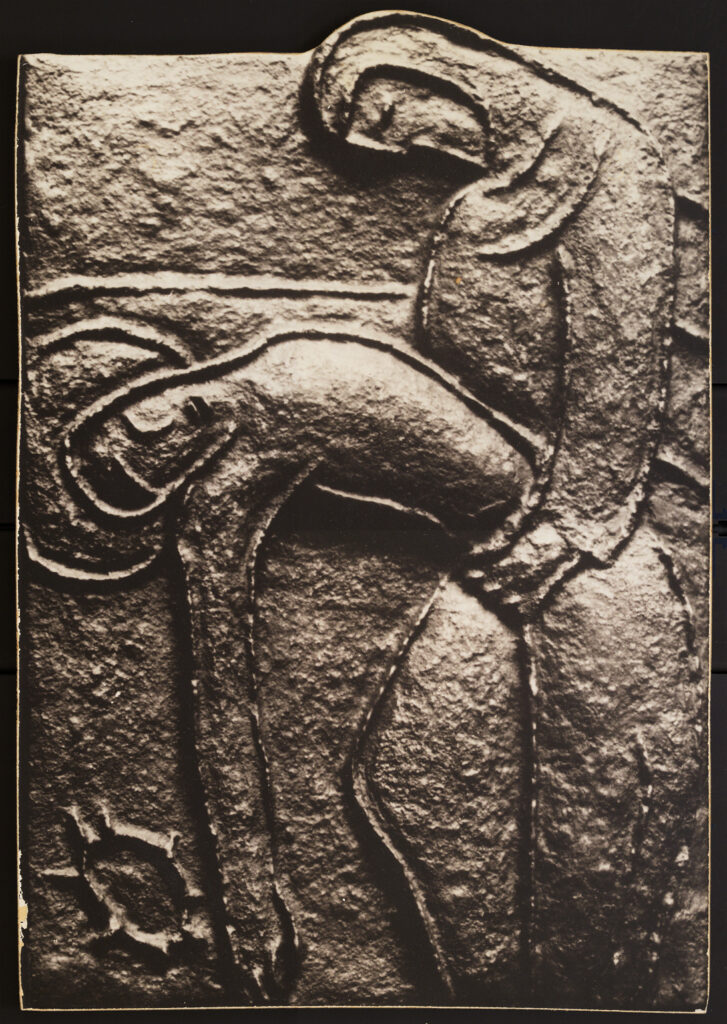

Monument to Mary Dyer did not immediately lead to any change of direction for the artist. She resumed her regular output of depictions of children and animals, often in the form of fountains. However, in 1961–62, Sylvia Shaw Judson made a second foray into religious art, creating a set of Stations of the Cross for a Catholic church, the Church of the Sacred Heart, Winnetka, Illinois, south of Lake Forest in the northern suburbs of Chicago.

Her low-relief rectangular Stations follow traditional iconography but the figures are pared back to almost geometric forms. She later revealed that each of the fourteen plaques represented an emotion, words which she “held in my mind as I worked and are unrelated to any liturgy.” To the courage and compassion she had associated with Mary Dyer, she now added acceptance, discouragement, agony and forgiveness. Quakers, when challenged about their relationship with the Biblical texts, often speak about the need to get behind the text, so as to be inspired by the same Spirit which inspired the Gospel writers. This was clearly Sylvia’s approach to the Stations, to encourage the viewer to reflect on the universal emotions which the Passion stories evoke.

Final years

Clay Judson died in 1960 and in 1963 Sylvia married Sidney Gatter Haskins, a British-born Quaker. In the same year she had the opportunity to teach sculpture at the American University of Cairo. This led to further years of travel—to the Mediterranean, to Hawaii and Japan, and even in the last year of her life, to the West Indies. She died at Ragdale in 1978.

Sylvia Shaw Judson was modest about her achievements, recognising that “Mine has not been a life calculated to produce an art of protest.” But in her emphasis on “the quiet eye,” as well as on animals as “the creature companions of our pilgrimage,” she speaks strongly to modern concerns. And in the development of Quaker art, her Monument to Mary Dyer remains a unique achievement.

Rowena Loverance is a Byzantine archaeologist and art historian. She has published sculpture finds from Byzantine excavations in Cyprus and Jordan, and her illustrated history, Byzantium (British Museum Press 1988), is in its fourth edition. Rowena worked for over twenty years at the British Museum, where she was Head of e-learning. She has wide interests in Christian art: (Christ, British Museum Press 2004 and Christian Art, British Museum Press 2007). She is the arts editor for The Friend, the UK Quaker journal. Her chapter on Quaker art has just been published in Variations in Christian Art: Mennonite, Mormon, Quaker and Swedenborgian.

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Sculpture or Suffrage: Alice Morgan Wright, by Jennifer Dasal

Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real Review, by Olivia Turner

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattler

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Science, Nature, and Music in the Art of Alma Thomas, by Erika Gaffney

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd