Guest post by Hannah Lyons, Curator of the Art Collection, the University of Reading

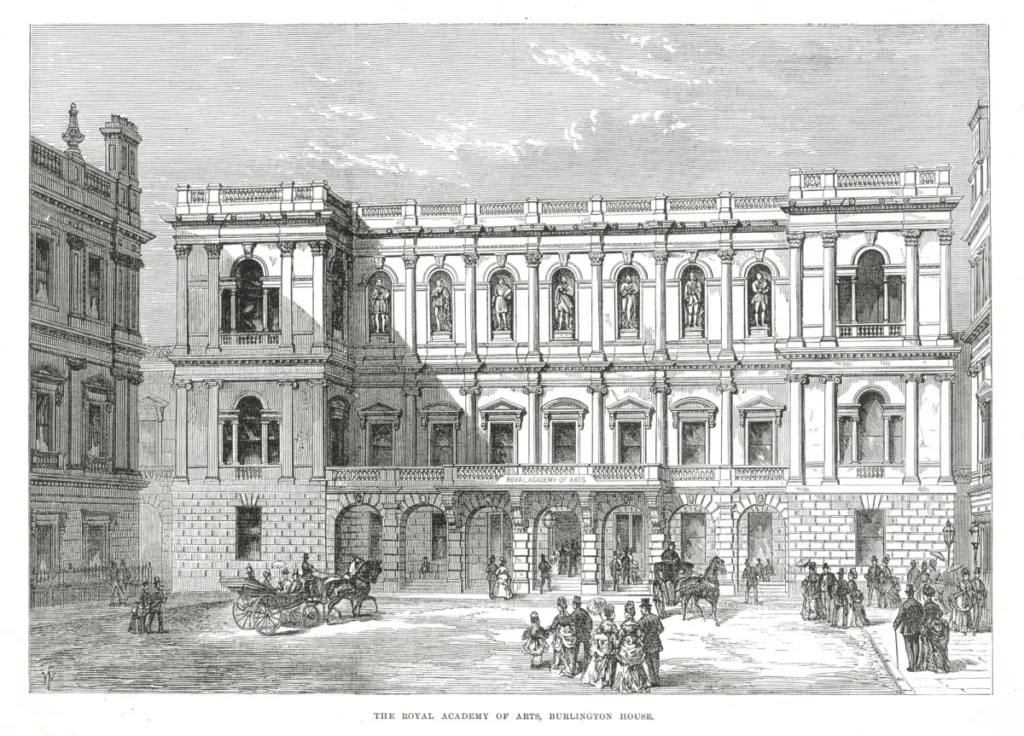

On 13 March 1883, the twenty-year-old Minnie Jane Hardman (née Shubrook; 1862–1952) formally enrolled at the Royal Academy (RA) Schools in London (Fig. 1). Ascending the steps to Burlington House, Piccadilly, where the RA Schools remain to this day, Hardman must have felt a twinge of pride mixed with nervous excitement. She was about to begin a free, six-year course at London’s oldest and most prestigious art school—a school that had only begun admitting female students a generation earlier, in 1860.

In 2023, 140 years after Minnie Jane Hardman first enrolled at the RA Schools, I started my job as Curator of the Art Collection at the University of Reading. It was during my first few weeks of sifting through prints and drawings in our Art Study Room that I encountered Hardman’s work for the first time.

Having researched the lives and output of eighteenth-century women printmakers for my doctoral research, I was broadly familiar with the names of many historic women artists working in London in this period. But when I came across Hardman’s drawings—some of which she signed “Minnie Jane Shubrook”—her name didn’t ring any bells. Who was this remarkable artist? After carefully working through the University’s collection of 125 Hardman drawings, I was astonished and keen to know more. How did this artist come to make such technically sophisticated works? And why was this collection here, in rather remarkable condition, at the University of Reading?

The Hardman Collection, University of Reading

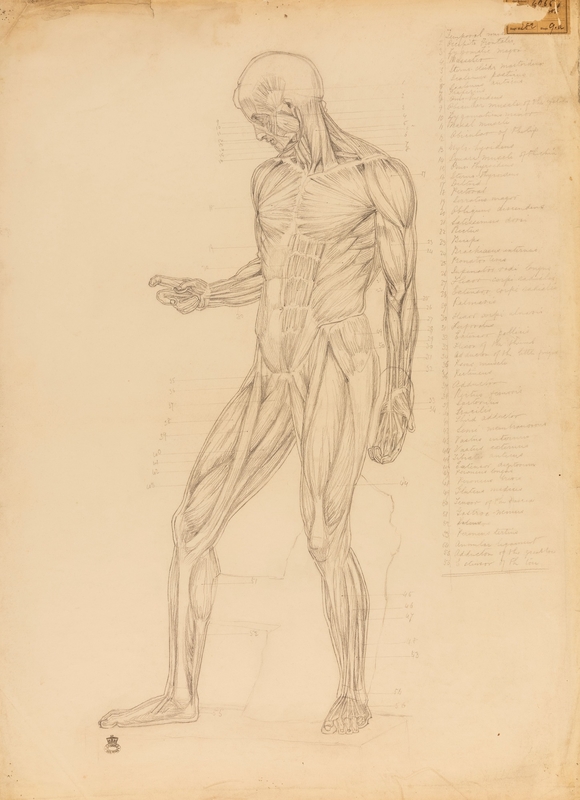

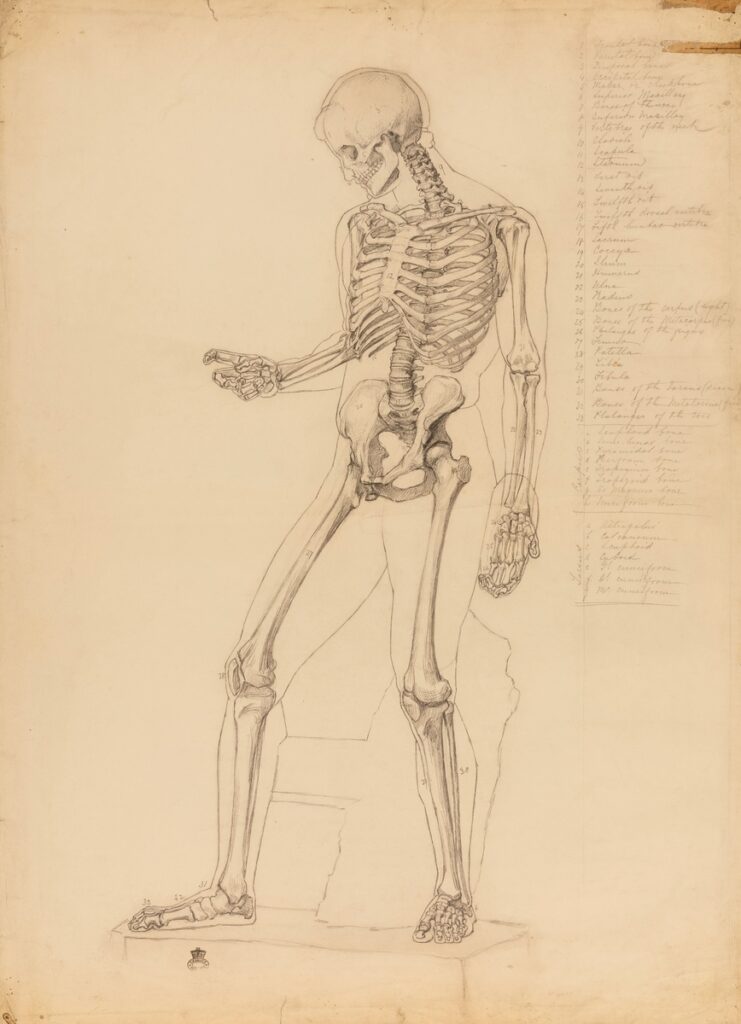

Constituting drawings after the antique, anatomical and life drawings, studies in perspective and landscape sketches, the University of Reading’s Hardman Collection demonstrates the hand of an astonishing gifted young student (Fig. 2).

Unusually, many of the drawings have labels and prize-winning stamps that identify Hardman’s training at the RA Schools, where she studied from 1883 to 1889. I shall admit that I did let out a little cry of delight when I came across a small book alongside her drawings. “Writing Album” contains 18 pages of press cuttings compiled by the artist throughout her career (Fig. 3). The Royal Academy did not usually collect student work, so the Hardman Collection provides important insight into the school’s teaching practices. It is also a window into the experience of female students at a time when the school taught some classes to women and men separately.

But how did these works arrive in Reading? Unfortunately, the origins of the Hardman Collection are not fully documented. The family made the donation to the University’s History of Art Department around 1992. The school’s leadership thought they would sit very well alongside the University’s Master Drawings collections, which was primarily used for teaching. The complete drawings collection became part of the University of Reading’s Art Collection in 2015. Thanks to generous support from the Tavolozza Foundation, the drawings were conserved and rehoused in 2018–19.

In December 2019, my wonderful predecessor, Dr. Naomi Lebens, organized for the display of a selection of the drawings at Hardman’s Alma Mater, in the Schools Corridor. And this month, three of Hardman’s drawings in graphite and charcoal are on display at Tate Britain’s Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain, 1520–1920 exhibition (Fig. 4). As the Curators of that show agree, Hardman’s rare and remarkable drawings deserve the attention of a wider public.

Applying to the RA Schools

Recent scholarly research has emphasized that large numbers of historic women artists were born into an artistic family or trained by male relatives. This is the case with Minnie Jane Hardman. Her father was the wood-engraver Lewis Charles Shubrook (1834–1913). About her mother, Jane Shubrook (née Wilson), unfortunately we do not at present have much information. A newspaper article of March 1890—preserved by Minnie Jane in her book of press cuttings—reveals that her father “taught her how to engrave upon wood when she was still quite a child.”

Prior to her admission at the RA Schools in 1883, Hardman had studied at the Islington School of Art under the tutelage of RA alum Henry Thomas Bosdet (1856–1934). Primarily known today for his designs for stained glass, Bosdet went on to become Curator of the Life School at the RA in 1883, the same year that Hardman enrolled. Bosdet likely encouraged and supported Hardman through the multi-stage application process, which can be unravelled through an examination of some of her drawings.

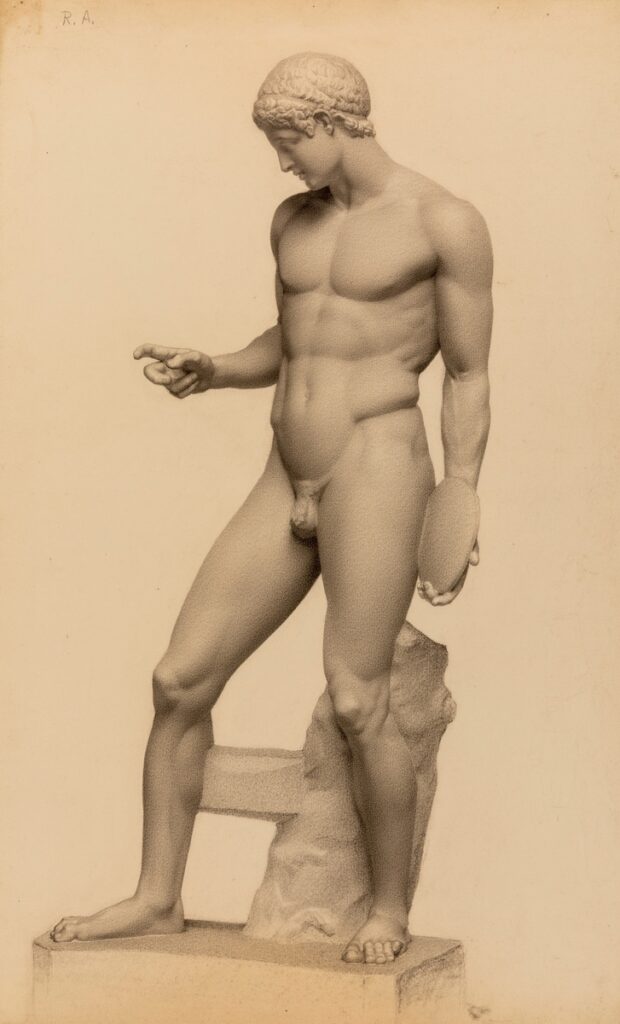

Application to the RA Schools was understandably thorough. First, Hardman had to submit a finished drawing “about two feet high of an undraped Antique statue” for the approval of the Keeper of the RA Schools, then Frederick Pickersgill (1820–1900). Pickersgill’s endorsement led to the “Probationary” stage. Then on 30 December 1882, Hardman had three months to produce a set of drawings from the Academy’s collections of the “Undraped Antique Statue, together with an Outline Drawing or Drawings of the same figure anatomized, showing the bones and muscles.” For this important part of her application, Hardman chose the cast of the Discobolus as her model (Fig. 5–7). Her drawings are clearly labelled “EXAMINED / SCH. WORKS,” revealing that they were approved by the RA Council.

The Antique School and The Ladies Painting School

With the preliminary stages over, Hardman’s formal tutelage began by copying casts in the Antique School. During this first year, she completed The Wrestlers, choosing the cast that John Flaxman, in his Lectures on Sculpture (1838), praised as “the greatest muscular display in violent action” (Fig. 8).

In 1883, Hardman signed the petition calling for the right of women students to study the partially-draped nude. The signers sent the petition to each of the forty Academicians, and The Athenaeum reproduced it. The document is on view alongside Hardman’s drawings in Tate Britain’s Now You See Us exhibition.

The Life School continued to exclude women until 1893. And even after their eventual admission, classes were still divided between men and women. Rather than proceed to the Life School with her male peers, Hardman spent the ensuing five years at the RA (from 1884 to 1889) in the Ladies Painting School. There she produced highly finished portraits, often of women, all fully dressed. In 1884, she won a silver medal for a sharply defined head and shoulders portrait of a young woman, drawn “from life.” Her surviving sketches of nude male figures are on a cheaper, lighter-weight paper than her academic drawings. These works reveal that she supplemented her formal training with extra-curricular instruction outside of the RA.

Life after the RA

Minnie Jane Hardman’s inclusion in Tate Britain’s exhibition is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for audiences beyond the University of Reading to engage with her work. Ideally the exhibition will encourage further research on her life and oeuvre, including the years after she graduated from the RA in 1889. Was she able to continue earning a living as a professional painter? Did she publicly exhibit her work? Did she run her own studio? What genres and media did she specialize in? Perhaps I’ll be able to return to this Art Herstory Blog in a few years’ time to update you on what I have uncovered. But for now, I urge you to visit the Tate Britain exhibition to see her astonishing drawings, alongside those of her female contemporaries, in the flesh.

Hannah Lyons is Curator of Art Collections at the University of Reading. Her PhD, undertaken with the V&A and Birkbeck, University of London, focused on the role, status and output of professional women printmakers, 1760–1830.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed