Guest post by Sarah Hardy, the De Morgan Foundation

Mary Evelyn De Morgan, née Pickering, was born in London on 30 August 1855 to very well-to-do parents. Her mother, Anna, was the daughter of Walter Spencer-Stanhope of Cannon Hall in Yorkshire, and her father was a successful lawyer and QC. They made the 500-mile round trip to Yorkshire to have her christened at the family church in Cawthorne, near Barnsley, welcoming her to a family and a faith that she would spend her whole life questioning through her artwork.

Early years

De Morgan was a precocious child who received an excellent education in languages, mathematics, and classics. From the age of 13 she began to write poetry, plays and short stories which would quite often end abruptly with a note that “the author could not finish due to being call away on more pressing matters.” The poems are truly beautiful, well developed and mature for a young author. In “My Love Lies Deep Below the Ground” she describes the grief of a young lover at her partner’s death, but laces the stanza with hope of reunification in the Spirit world aided by the Angel of Death. De Morgan was taken to church regularly by her father. It seems that the Christian ideals of faith in everlasting life—and charitable giving particularly—resounded with the young artist attempting to reconcile her place in the middle-class world she was born into.

Some twenty years after writing her poem featuring the Angel of Death, De Morgan committed her leitmotif to paint in a picture called Love’s Passing (1883). She painted it in the same year she met her future husband, the potter William De Morgan, who was 16 years her senior and possibly the inspiration for this painting. On the far banks of a river, the hooded Angel of Death leads a lonely elderly woman to her death. In the foreground we see her in her youth with her companion, listening to the music of love. The book the couple have discarded carries prose from Tibullus’s Ellegies, which describes being so in love that one might experience a premature grief: the fear of their love dying and being alone.

Training and Technique

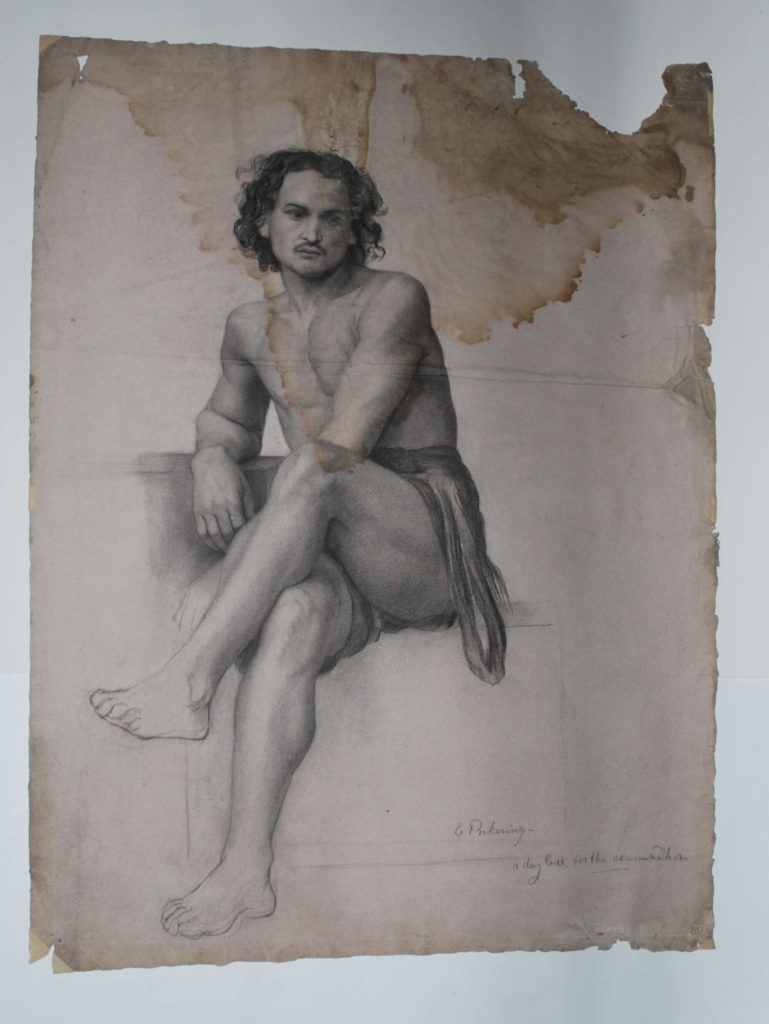

De Morgan’s imagination drove her to become an artist. While her mother was against this unladylike pursuit, her father supported his daughter by employing at least three drawing tutors. Eventually he allowed her to study at the Royal College of Art, which she attended for six months before entering the Slade School of Art in 1873. Arriving at the Slade must have felt like being reborn. Evelyn was finally allowed to study from the life model, something that would have been denied to her at her previous school because she was a woman. But the Slade was radical in its approach to teaching, with male and female art students attending the same classes.

De Morgan dropped “Mary” as a first name at this time, adopting her unisex middle name to protect her from gender prejudice and she went on to succeed. In her first year she won a full scholarship for study. By the time she left in 1876, she had racked up a number of prizes and medals for her skill in copying from the antique, her compositional work and her study from the life model. Through her scholarship, she was permitted to attend classes in other schools at University College, where the Slade was based. She chose the gruesome, physical anatomy lessons usually reserved for men. This improved her grasp of the human form; as a result, her studies from life are robust, believable and lifelike.

Italian Influence

In 1875, her second year at the Slade, De Morgan took her first independent trip to Italy with her first cousin, the sculptor Gertrude Spencer Stanhope. They visited Perugia and Assisi, and stopped in Florence with their uncle, the artist John Roddam Spencer Stanhope. During this time, De Morgan was able to visit sixteenth-century Italian altarpieces and frescoes in their original churches, and to examine the work of Renaissance artists at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

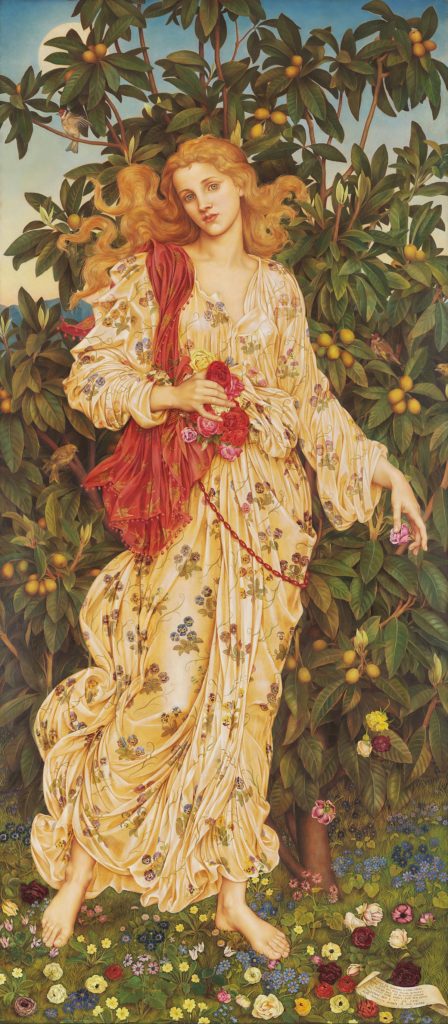

She was intrigued by the work of Botticelli and made watercolour copies of his work. It seems that Primavera and The Birth of Venus were of particular importance to Evelyn, and were certainly the inspiration for her own painting Flora (1894). The Spring goddess in her finery is set in a blooming meadow under an Italian summer sun. De Morgan has painted her in gold, so that she literally radiates and illuminates the world around her. This picture not only shows her debt to Botticelli, but her own mastery of easel painting. The large picture is still in flawless condition today, due to her careful preparation of the canvas and thin paint layers.

Feminism

In 1889, De Morgan signed the Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage, publicly presenting herself as a feminist and advocate for gender equality. Although De Morgan did support the Suffrage movement, she was not an activist, preferring a quiet, subversive protest through her painted moral masterpieces. The Captives (c.1915) shows women overwhelmed by the phallic stalagmites and stalagtites of the dark, dank cave in which they are held. However, they rise above the demons they cannot see or feel. They use their inner power to look for the light at the end of the tunnel. De Morgan understood women were oppressed, but had hope they could rise above it and escape. Unusually for the era, De Morgan’s own marriage was one of equality; William De Morgan was an active campaigner in the Women’s Suffrage Movement.

A Pre-Raphaelite artist?

The revolutionary Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had disbanded by the time Evelyn De Morgan was born in 1855; and yet they were so influential that their artistic ideals continued to permeate art school teaching, exhibitions, and stylistic movements well into the twentieth century. De Morgan’s work is sometimes referred to as later, or second generation, Pre-Raphaelite. De Morgan made a series of pictures at the turn of the century which are stylistically her most Pre-Raphaelite.

With a truth obtained from careful study of nature, luminosity of colour, clear links with Renaissance art and a moral message, De Morgan’s The Hourglass (1904) is a prime example. Moreover, the model for this picture was Jane Morris, the embroiderer and wife of William Morris, the Victorian designer, poet and Socialist. Jane was a favourite model of the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1870s, but came out of retirement to pose for De Morgan, making this picture particularly significant.

War and Peace

De Morgan was born during the Crimean war and lived through the Boer Wars and First World War. She was strongly opposed to fighting and violence, viewing conflict as a tool for eventual peace. Two years into the First World War, she held a benefit exhibition at a studio in Fulham. Here she showcased symbolic pictures that directly opposed the evil and the horrors of war. They feature angels and rainbows as hopeful symbols of a peaceful outcome to the war, which she depicts as hellish demons and dragons. She gave the proceeds from this exhibition to the Red Cross, actively supporting humanity in crisis during this period. The painting The Red Cross was a key work in this exhibition. It depicts Christ collecting the souls of soldiers from unmarks graves, undoubtedly providing comfort in faith for visitors to the 1916 exhibition.

Spiritualism

From the time of her meeting with William De Morgan in 1883, the subject matter of Evelyn De Morgan’s pictures shifts from mythological and biblical to overtly Spiritualist. She painted women in prisons in as a visual metaphor for the soul trapped in the human body awaiting emancipation. The passing of time depicted by personified forms of night and day, or the changing seasons, became favourites of De Morgan’s. She understood the human soul as evolutionary progressing through life and after death. The reason that her interest was piqued when she met William De Morgan was undoubtedly her introduction to his mother Sophia Frend De Morgan, a social reform campaigner and practicing Spiritual medium. The De Morgans were inspired by Sophia’s work to take part in séances. They recorded their conversations with the spirit world in a 1909 publication The Result of an Experiment.

De Morgan’s most overtly Spiritualist picture came towards the end of her life, upon the death of her husband William in 1917. The Passing of the Soul at Death (1917) shows the soul of a dying woman as a rainbow mist being welcomed by a Spirit. Visually, it is similar to the design De Morgan made for the couple’s joint headstone; a fitting tribute to two artists who firmly believed in life after death.

In her diary at the age of 17, De Morgan wrote “art is eternal, life is short.” Just as she believed would be the case with her spirit, her art and reputation have outlived her. Today she is recognised as a ground-breaking and unique artist.

Evelyn De Morgan’s artwork is owned and cared for by the De Morgan Foundation, which was established by Evelyn’s sister in 1965. The Foundation runs an Accredited Museum at Cannon Hall in Barnsley, and works with other museums and galleries to present the collection in exhibitions and displays. Currently the Foundation has loaned works to the Delaware Art Museum for its exhibition A Marriage of Arts & Crafts: Evelyn & William De Morgan, which runs through February 19, 2023. Follow the De Morgan Foundation on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Sarah Hardy is the curator and Director of the De Morgan Foundation.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

The word is ‘elegy’, not ‘ellergy’.

Thank you!!