by Erika Gaffney, Art Herstory Founder

Two and a half years in the planning, A Room of Her Own: Women Artist-Activists in Britain, 1875–1945 is well worth The Clark team’s considerable time and effort.

According to exhibition curator Alexis Goodin, The Clark’s acquisitions of works by two British women artists were the seed that blossomed into this show. In 2022 the museum acquired The Garden Studio, by Anna Alma-Tadema. And in 2022, The Clark added to its collection Evelyn De Morgan’s drawing Head of a Youth and her painting The Field of the Slain.

Diversity with cohesion

A Room of Her Own features 87 works by 25 British women artists—or more accurately, women artists who worked in Britain. The Clark owns six of the works on view. The remainder are loans. More than half of the loans are from private collections or British collections (and one French collection). Thus the show offers Clark visitors a wonderful opportunity to view objects they’d otherwise see—if at all—only by traveling to and around the UK.

Diversity of mediums and backgrounds

Among the works the curatorial team assembled are paintings, drawings, prints, stained glass, embroidery, and other decorative arts. Books by the artists are also on display. Goodin acknowledges that the representation is not encyclopedic, and that the selection process was organic. She notes that her hope in bringing together such a diversity of objects is “to show the depth, breadth and richness of artistic production by women artists of this period.”

The show succeeds in this goal—the variety of objects does make for a rich and interesting display. Some of the non-frameable works are not only impressive on their merits, but also because of the special challenges that their transport and handling involves.

The organizers further diversify the galleries with the large shadow-box photo-murals throughout. These murals depict the artists at work, whether alone in their studios or in a community context.

Diversity is also apparent in the women’s life experiences. Some artists were traditional wives; some, like Vanessa Bell, rejected traditional family structures. After her widowhood, Helen Allingham supported three children as a single mother. Nan Hudson, Ethel Sands, May Morris, and Mary Lowndes formed lifelong domestic partnerships with women. Gluck rejected gender norms in both appearance and relationships.

Cohesion

Despite the abundant diversity of mediums and life stories, A Room of Her Own never feels scattershot or disjointed. Among the factors that provide a cohesive framework are that all of the featured artists were professionals. Each of the 25 women in the show exhibited and sold her work. And each was born in the nineteenth century, although in some cases only just barely.

And perhaps most important, each was in one way or another an activist, as well as an artist. As The Clark’s press release states, “The activism of these artists went beyond their profession. Through unconventional personal choices, creating community in their neighborhoods, and political advocacy in causes such as women’s suffrage, wartime service, or antiwar protest, the artists of A Room of Her Own enacted meaningful social and political change. These efforts created opportunities that helped these women thrive as artists and claim much-needed space—both physical and psychic—for themselves, their contemporaries, and future generations.”

Thematic organization

Each of the four galleries of A Room of Her Own centers on a space in which the artists operated. These “rooms” include the home; the studio; art schools; and exhibition sites.

There are several benefits to organizing the show according to venues in which British women artists had a presence. It is a useful lens through which to explore different kinds of activism. Also, this structure supports the integration of the different artistic mediums.

And in some cases it allows for the presence of an artist in more than one gallery. Some of the artists—Vanessa Bell, May Morris and Evelyn De Morgan among them—are represented in the exhibit with multiple works. By integrating their art throughout the show, the organizers ensure that they don’t dominate it. And for the viewer, seeing an artist’s name in a subsequent gallery is like running into an old friend.

Highlights

Different artworks will, of course, resonate differently for each visitor. For this viewer, the highlights are:

- The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, by Mary Lowndes. This stained-glass window arrived in Williamstown in three separate crates. The museum collaborated with a (woman) stained-glass artist in North Adams to reassemble the window. It is wall-mounted within one of the galleries, with a lighted cavity behind it so that viewers experience it to best effect.

- Maids of Honour panel, designed and embroidered by May Morris; and Flowerpot panel, embroidered by May Morris. It was a revelation to see that the support for the Maids of Honour panel is transparent; this feature is not readily noticeable in reproductions. One marvels at the skill and patience it must take to work with what seems an unforgiving medium. Likewise the gold thread in Flowerpot inspires awe, not only for the luster it adds, but for the embroiderer’s ability to integrate it with wool to create the picture.

- Mater Triumphalis, by Annie Louisa Swynnerton. This painting is striking for its sheer size, as well as for its Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics and its thought-provoking subject matter.

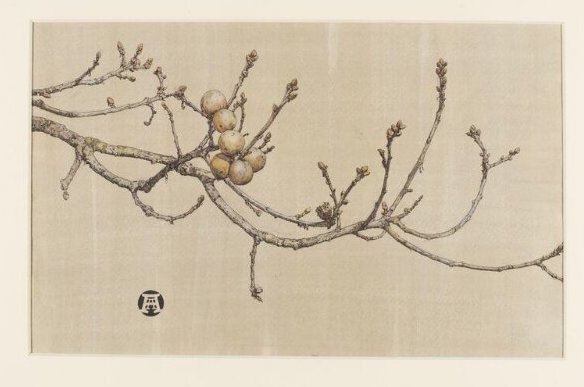

- Oak Apples and Blue Tit’s Breakfast; and The Art of Pastel, by Anna Airy. Your correspondent was vaguely familiar with Airy’s war art, but her botanical art and her status as an author were a surprise. The show includes examples of her war paintings (in oil), as well as the botanical drawings. It is interesting to note the different style of signature for each. In the oil paintings, the artist uses her first initial then spells out her surname in cursive. On the botanical art, she signs with a mark: two stylized white “A”s, one inside the other, within a dark circle.

- Ten plates from The Famous Women Dinner Service, by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. This is a bucket-list item—what a thrill to stand before even a portion of the 48-plate project! One can observe up close the borders the artists used to categorize the featured historic and contemporary subjects as queens, women of letters, beauties, dancers, and actresses.

Collateral

The museum shop has compiled an impressive selection of books about the show’s featured artists. The 288-page exhibition catalog—which technically won’t be published for another month—is available there for purchase.

On August 2 at The Clark, author and art historian Rebecca Birrell delivers the lecture “Corruptive…Destructive:” Women Artists Paint The Nude, 1875–1945. Birrell’s talk will explore how artists including Vanessa Bell, Evelyn de Morgan, Gwen John, and Winifred Knights overcame moral and pedagogical constraints to paint nudes.

Readers interested in British women artists of the period will want to know about the Eiderdown Books series Modern Women Artists. Volumes to do with artists in The Clark’s show include Nina Hamnett and Laura Knight. There is also a relatively recent prize-winning book about Winifred Knights,

Conclusion

With this show, The Clark exposes its visitors to an impressive diversity of Victorian and modern British women artists and their works. At least some of the artists have begun to achieve name recognition with 21st-century art-lovers, but that doesn’t mean their works are easily accessible. And some of the artists are in very early stages of rediscovery. For those of us who missed Now You See Us in the London in 2024, it offers an opportunity to experience at least one chronological segment of that blockbuster exhibition. And amazingly, there are no restrictions—as long as their flash is off, viewers can take all the photos they like!

Past, current and future exhibitions with women artists of the period

For those art lovers who cannot see A Room of Her Own, or for those who would like to see more work by some of the featured artists, luckily there are (or will be) opportunities.

- Elizabeth and Stanhope Forbes: A Marriage of Art is on at Worcester City Art Gallery & Museum through June 29, 2025

- Vanessa Bell: A World of Form and Colour is on at Charleston through September 21, 2025

- May Morris: Art and Advocacy is on at Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum through October 5, 2025

- Evelyn De Morgan: The Modern Painter is on at Guildhall Art Gallery through January 4, 2026

- Winifred Nicholson: Cumbrian Rag Rugs will run at The Hub in Sleaford from July 19–November 16, 2025

- The major international solo exhibition Gwen John: Strange Beauties opens at Amgueddfa Cymru–Museum Wales in February 2026; it travels to National Galleries of Scotland, then the Yale Center for British Art, and finally Washington DC’s National Museum of Women in the Arts

- Starting in November 2026, Tate Britain hosts Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant

Artists included in A Room of Her Own

For readers who may wish to know what artists the show includes, here is the complete list. There are works by Anna Airy; Helen Allingham; Anna Alma-Tadema; Vanessa Bell; Evelyn De Morgan; Elizabeth Adela Armstrong Forbes; Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale; Gluck; Laura Sylvia Gosse; Nina Hamnett; Anna Hope “Nan” Hudson; Gwen John; Louise Jopling; Lucy Kemp-Welch; Dame Laura Knight; Winifred Knights; Clare Leighton; Mary Lowndes; May Morris; Winifred Nicholson; Gwen Raverat; Ethel Sands; Marie Spartali Stillman; Marianne Stokes; and Annie Louisa Swynnerton.

A Room of Her Own: Women Artist-Activists in Britain, 1875–1945 is on at the Clark Art Institute through September 14, 2025.

Erika Gaffney is Founder of Art Herstory. Follow Erika on LinkedIn, Facebook, and/or Bluesky.

More Art Herstory blog posts about Victorian and modern British women artists

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews

Museum exhibitions about historic women artists: 2025

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney