Guest post by Julie Nash

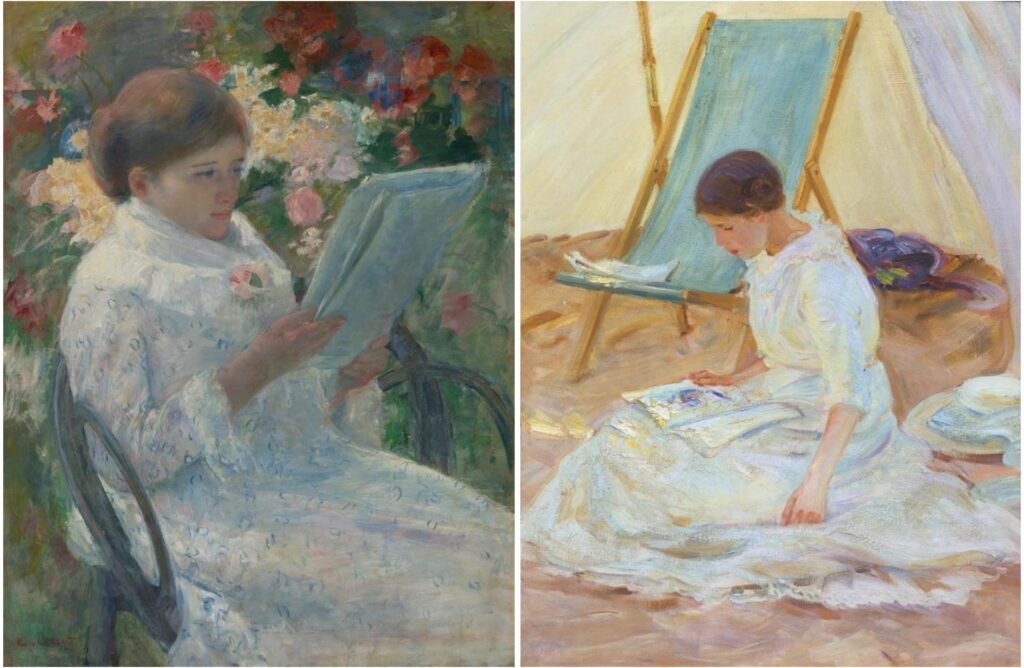

The Art Gallery of Ontario’s groundbreaking exhibition Cassatt – McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds explores the lives and work of two germinal artists at the turn of the twentieth century. American Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926) and Canadian Helen Galloway McNicoll (1879–1915) both radically chose to pursue professional careers outside their countries of birth. Though the two artists never met, they worked in a parallel Impressionist manner and were compared in their lifetimes in the press. As Henri Fabien of Montreal’s Le Devoir wrote: “Miss McNichol [sic] especially shines in her small picture of a young girl and a baby, where the richness of her color and the mastery of her brushwork make one think of Mary Cassatt.” Fabien’s November 1913 comparison of McNicoll’s painting with the works of Cassatt on the occasion of the Thirty-fifth Annual Exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts capped a significant year for both artists.

Cassatt’s Cachet

By 1913, Cassatt had long been a key figure within the European and North American art worlds. Her paintings were accepted to the Paris Salon in the early 1870s, but she cemented her status as a leading modern artist by participating in four of the original Impressionist exhibitions from 1879 to 1886. From 1890 to 1891 she experienced a period of intense innovation in printmaking, resulting in her celebrated “Set of Ten” color prints. She was soon commissioned to paint a mural titled Modern Woman for the Women’s Building at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The proceeds allowed her to purchase an estate on the outskirts of Paris. In the ensuing years she built a successful and profitable professional network, exhibiting and selling her work abroad and at home.

The year 1913 precipitated a major gain to Cassatt’s professional status. Though she had been the subject of a number of articles and exhibition reviews by this time, the first monographic book about the artist, Achille Segard’s Mary Cassatt: A Painter of Children and Mothers, was published in Paris in French. A history of Cassatt’s life and work up to that time, it also included a brief interview with the artist herself in which she recounted her family history and early years. The author charted Cassatt’s oeuvre alongside a detailed discussion and reproductions of many works. He concluded: “She is the painter of mothers and children. She has created almost countless variations of this infinite and inexhaustible motif. None of them are repeats. This is not insignificant. Some stand out as a reasoned opinion on what is essential in humanity.” Segard’s text would serve as the definitive resource on Cassatt for decades to come.

Text Meets Paintbrush

Among the works that feature in Segard’s text is Cassatt’s Maternal Caress. At the centre of this painting, gripping hands convey a charged interconnection between woman and child. While the painting’s title suggests an affectionate embrace, the caretaker’s firm grasp on the child’s arm may suggest a struggle. Cassatt’s works frequently feature highly tactile interactions that call attention to the demanding labor of childcare. Cassatt—and later McNicoll—subtly pushed against societal expectations of the period that required a woman to paint perfectly content mothers. Their work thus allows viewers to find their own experiences reflected in the art. While Cassatt’s paintings of caregivers are far more complex than Segard allowed, she likely understood that these scenes were more marketable and would promote the sale of her work.

The book was released just as cataracts began to affect Cassatt’s eyesight. She was soon unable to practice her art, but she continued to work with dealers and collectors. She played a significant role in helping build collections of European art—particularly French Impressionism. Some would later form the foundations of major museum collections, including the Havemeyer Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

McNicoll’s Professional Honors

While Cassatt built her professional network in Europe before turning her attention to the American scene, McNicoll gained recognition in Canada long before she was accepted abroad. Having studied at home then trained in London and St. Ives for several years, she permanently settled in England and sent paintings back to Canada for exhibition. She had works accepted to the annual Salons of the main Canadian institutions as of 1906. In 1908 she was awarded the Art Association of Montreal’s inaugural Jessie Dow Prize, heralding her skill as a professional painter after nearly ten years of study. By 1913 she was well-established as one of Canada’s greatest Impressionist painters. A Canadian press clipping from April 12 summarized: “her style is broad and simple, and she follows the modern school of sun-lit effects without any affection, but absolute sincerity.”

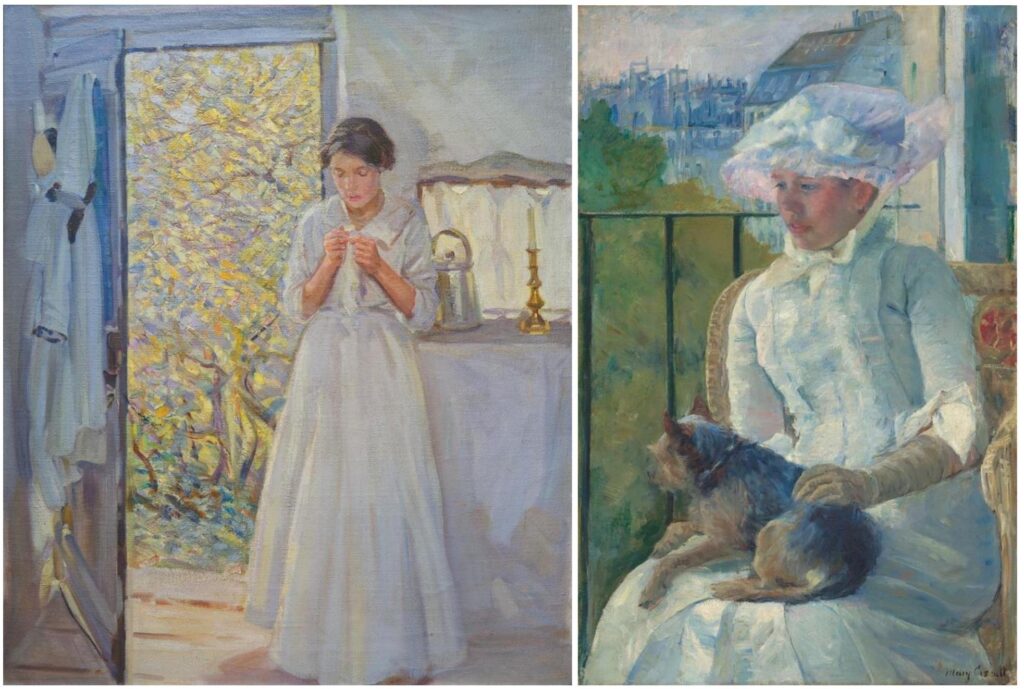

Though England was initially slow to recognize McNicoll, 1913 witnessed her election as an associate of the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA), an honor conferred by what she described as a group of “many angry and helpless looking men” in a letter to her father on March 28. Canadian press notices reporting her election included photographs of the artist and her studio. They observed: “considering that there have been only eight elections this year it is particularly gratifying to Canadians that Miss McNicoll should be one of the chosen.” This was a major accomplishment for an artist who was both a woman and not English-born. McNicoll was awarded the maximum number of three paintings hung in the associated exhibition. Among these was the first in a series set in her London studio, paintings of women engaged with their own thoughts. The series marked a monumental change to her subject matter just as she was on the cusp of international professional recognition.

Transatlantic Accolades

McNicoll soon after travelled to France with friends and artist colleagues Dorothea Sharp and Marcella Smith. She painted both women engaged in their work on a beach in the south of France, which she exhibited in the autumn iteration of the RBA. It was shown alongside a work titled A Bedroom, which could possibly be the intimate setting represented in the AGO’s own Interior. McNicoll’s deliberate decision to show works highlighting the lives of women within such a venerable exhibiting body counters sentiments she expressed to her father earlier in the year: “It was the older members who didn’t like my things, one old man said … ‘If that picture is right then the National Gallery is all wrong.’ … I must send some of my older ones there I guess.” Instead, she shifted her approach and depicted women as intellectual, engaged, and contemporary.

McNicoll continued to send her most recent and ambitious works to the RBA’s biannual exhibitions, increasing the scale of her figures positioned in both exterior and interior worlds. Not to be outdone, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts soon after conferred official recognition on McNicoll by electing her an associate member, the highest attainable level for a woman at this time. She was shortly after awarded a major prize for Under the Shadow of the Tent when it was brought to Canada and exhibited in Montreal. This honor further signalled the recognition she was now garnering on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Right to Vote

On March 3, 1913, the Woman Suffrage Procession of 5,000 delegates marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. in support of women’s enfranchisement. This march was mirrored by events in France, England, and Canada, of which Cassatt and McNicoll were certainly aware. In fact, Cassatt lent a number of paintings to the Exhibition in Support of Woman Suffrage at New York’s Knoedler Gallery organized by her friend Louisine Havemeyer, the American activist and collector. As Cassatt wrote to Havemeyer in July 1915: “Do you think if I have to stop work on account of my eyes I could use my last years as a propagandist? It wont [sic] be necessary if the war goes on, as it must. Women are now doing most of the work.” For her part, McNicoll joined the London electoral register in 1915. It has also been suggested that her canvases from 1913 to her sudden death in 1915 contain political allusions, though the degree of her activism is the subject of ongoing research.

In Between Worlds

In works such as Young Girl at a Window and The Open Door, Cassatt and McNicoll present women in white dresses near an opening to the outside world, yet neither looks out. They turn instead to the mental space of their inner worlds. These paintings speak to the experiences of in-betweenness that both artists shared throughout their lives. Professional status was central to Cassatt’s and McNicoll’s personal definitions of success. As foreigners in Europe and as women fighting to gain access to a male-dominated field—which was the case for women in most professions during the period—this was a bold ambition. In an era when women were expected to marry then raise children, Cassatt and McNicoll defied these expectations. The events of 1913 demonstrate that both artists successfully gained professional recognition, while radically putting the full lives and complex thoughts of women and children on display.

Julie Nash is an art historian whose areas of study include turn of the twentieth-century connections between Canadian and international art. She was the Curatorial Assistant for the exhibition Cassatt – McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and has also worked at the National Gallery of Canada.

Cassatt – McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds is on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario until September 4, 2023.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2024

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely