Guest post by Jun Dong, independent curator

Entering quietude

The first impression on entering Ethel Stein: Master of the Loom at Sapar Contemporary is quietude. The room feels weightless, filled with works that seem to absorb sound rather than reflect it. On the walls, Stein’s weavings shimmer faintly, the light sliding across their surfaces as though over water. Nothing insists on itself; the power of the exhibition lies in restraint.

Her textiles—composed of cotton, linen, and damask, a reversible patterned fabric defined by the contrast between matte and lustrous threads—hold warmth as if touched by time. They feel like objects that remember: threads carrying traces of care, patience, and domestic rhythm. The material itself has a temperature, the warmth of home. One thinks of garments once woven by mothers or grandmothers, of patterns that live on in memory. All of this is reflected in her latest solo exhibition, which gathers works spanning decades of disciplined experimentation, from the geometric abstractions of the 1990s to the tender figural weavings of her final years.

From Geometry to Gesture

The exhibition traces Stein’s evolution from the disciplined geometry of her mid-career to the quiet affection of her later work, revealing how technical rigor became inseparable from emotional clarity. Rust Abstract (2005), placed near the gallery’s center, announces her mature language: an austere grid in slate and ivory that flickers as light moves across its mercerized cotton surface. What first appears static turns atmospheric—the warp tightening and loosening like breath. The sense of architecture dissolving into air recalls the Bauhaus precision she absorbed from Josef Albers, yet the warmth of the material roots the work in lived experience rather than theory.

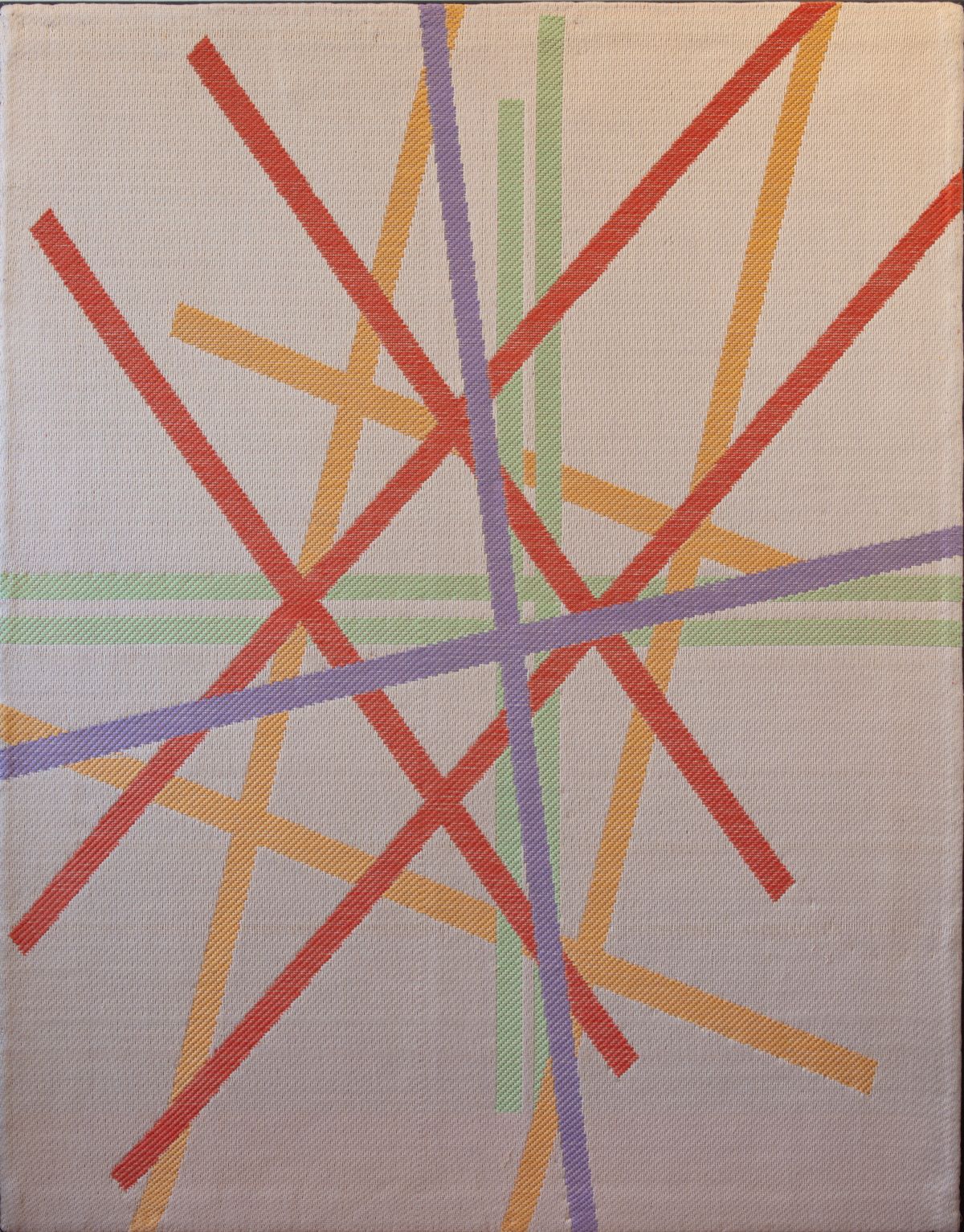

Across from it, Jack Straws (2008) picks up that rhythm with brighter inflection: red, lavender, and yellow lines, shaped rather like straws on top of each other, crisscross in a lattice that feels spontaneous yet perfectly controlled. The interplay of chance and calculation—a reminder of Russian avant-garde artists—mirrors Stein’s larger dialogue between emotion and order; her threads behave like gestures held gently in place.

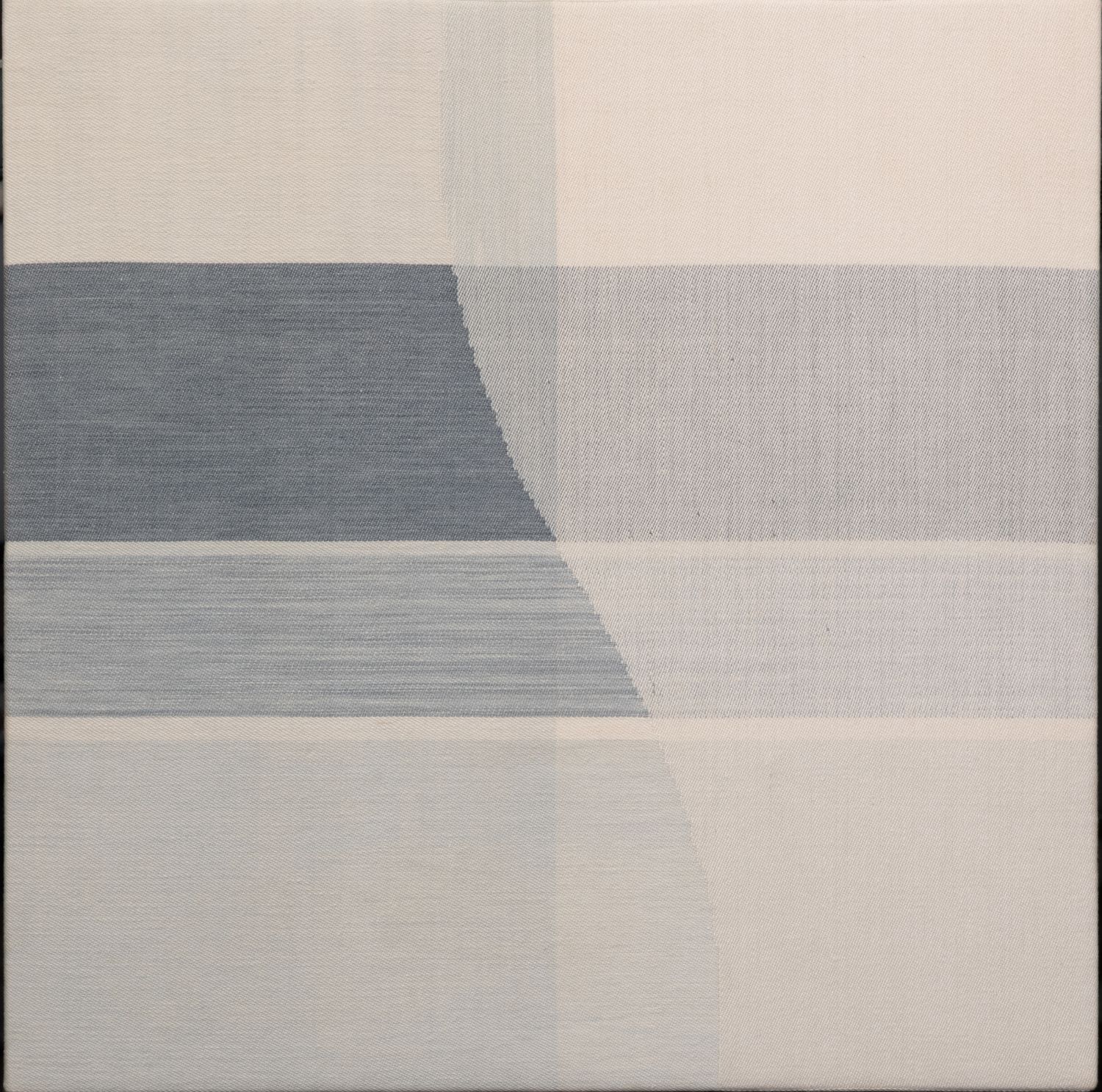

This conversation continues in Indigo Curve, woven in shades of grey and blue. What looks like a flat monochrome gradually separates into two planes—a double-cloth construction that trades light between its surfaces. Certain threads appear to hover above the rest, catching illumination and releasing it in pulses. The effect is not optical illusion but genuine depth: the fabric seems to breathe. Standing before it, one feels both the precision of the technique and the serenity of its result. These works, viewed together, articulate the tension that defines Stein’s art—the pull between structure and softness, intellect and warmth, modernist rigor and domestic tactility.

Abstraction Becomes Affection

Across the gallery, her later pieces transform that discipline into tenderness. In Polly (Portrait of a Dog) (2012), Stein translates her abstract logic into quiet affection. The black dog, woven from interlacing tones of grey, charcoal, and blue, rests against a pale linen ground that shimmers with the same luminosity found in her earlier grids; his tongue playfully sticks out from the otherwise monotone composition. What seems playful at first reveals the same rigor of structure: each thread calibrated to hold both form and emotion. The dog’s dark, ochre eyes catch the light like a flicker of recognition, breaking the symmetry of the composition and animating it with the faintest pulse of life. Even at ninety-five, Stein treated the loom as an instrument of perception—turning the familiar into geometry, emotion into pattern, and touch into thought.

Her smaller works from the 1990s bring this intimacy even closer. Untitled (Red-Headed Woman) and Untitled (Leaves), displayed side by side, seem to converse in silence—the human and the natural, warmth and stillness, presence and reflection. In Red-Headed Woman, the rounded figure, seen from behind, glows with a childlike softness. Woven from linen and velvet, the red fibers catch the light as if warmed from within, evoking the tenderness of a memory rather than a portrait. In Leaves, velvet absorbs and releases light in ripples of green, like wind moving through branches. Here, nature becomes texture, and perception becomes touch. Together, these works distill Stein’s central pursuit: to translate fleeting sensations—breath, gesture, light—into structure. She replaces brushstroke with thread, gesture with patience, preserving the traces of life within the weave.

The Architecture of Light

Technically, Stein’s mastery is absolute but never ostentatious. Lampas and damask structures allow light to travel through her surfaces, while the balance of matte and sheen creates an internal glow that feels almost alive. Nothing is ornamental; every decision carries weight. She understood that weaving, unlike painting, builds from within—the image is not applied but incarnated, the pattern living in the structure itself. Time is folded into the fabric: hours condensed into the density of fiber, memory made tangible through rhythm.

Sapar Contemporary’s presentation honors this meditative intensity. The works are spaced with generosity, their colors resonating softly against one another. In her world, vision begins with touch, and this exhibition—organized with the artist’s family—channels part of its proceeds to The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Textile Conservation Department and its programs for blind and low-vision audiences, a tribute made more poignant by the fact that Stein continued to weave even after losing much of her sight.

Threads of Continuity

Seen together, the selection underscores a consistent emotional temperature: muted colors that radiate warmth, abstraction that carries the intimacy of domestic life. The curatorial decision to interlace early and late works across the gallery rather than follow chronology reinforces this continuity. What might have been a survey instead reads as a conversation—between grid and gesture, discipline and tenderness, modernism and memory. Stein’s art reminds us that thought can take form through touch. The density of her threads recalls worn fabric; the rhythm of her weaving mirrors the body’s pulse. She turns associations of home and care into abstraction without erasing their softness, bridging the world of the hand and the mind, transforming craft into cognition.

Simplicity becomes depth, patience becomes power, and warmth becomes thought.

Ethel Stein: Master of the Loom is on view at Sapar Contemporary, 9 North Moore Street, New York, through November 17, 2025.

Jun Dong is a New York–based independent curator and writer. Her research focuses on materiality, perception, and the sensory language of contemporary art. She holds a BA in Exhibition Economics and Management and is pursuing her MA in Art Business at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. Her work explores how artists translate structure and emotion through material processes, particularly in works on paper and textile-based practices.

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy

Eunice Golden: Making Space for Female Eroticism in the Art Institution, by Isabel Gilmour

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by Paula Butterfield

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattley

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Isabelle Gapp

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers