Guest Post by Isabelle Gapp, Incoming Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Toronto

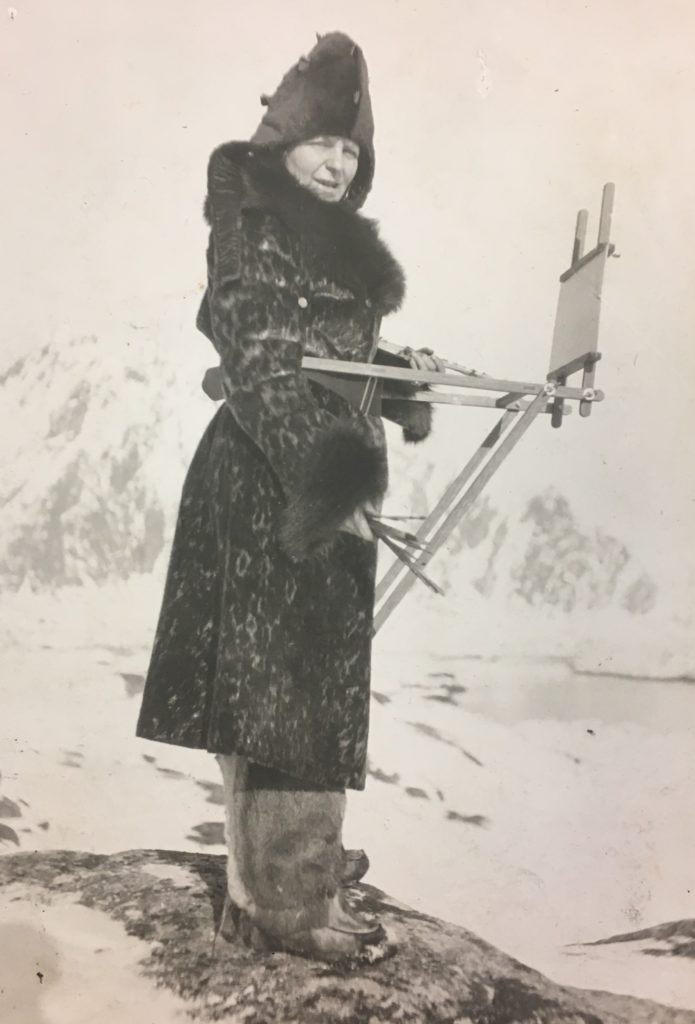

Imagine for a moment a woman clad in reindeer-fur breeches, the coarse hair of the animal hide layered above nutukas (traditional Sámi footwear), while a fur coat, with the mottled pattern of sealskin, extends down to the knees. A lavish fur collar, sleeves and hat are distinctly extravagant, yet warming, against the bleached-white of the Lofoten landscape beyond. A peculiar easel is strapped to the artist’s thighs and waist, and appears to allow her to paint with increased movability. A canvas board, perhaps that of an oil sketch in progress, is mounted to the easel, while paint brushes and a palette occupy either un-dressed hand. This image taken from a holiday photo album is that of the Swedish painter Anna Boberg (1864–1935), a self-described “polar researcher” and Arctic artist.

For over thirty years, from 1901 until 1934, Boberg frequently visited the Arctic, specifically the Lofoten Islands off the Norwegian north-west coast. Here, she and her husband constructed their own home and studio overlooking the Svolvær harbour, a prominent village in the Norwegian cod-fishing industry. This lifestyle is also documented in Boberg’s Swedish-language autobiography Envar sitt ödes lekboll (1934).

Here, I briefly introduce Boberg’s life, travels and artwork and her place in a history of white, Western women in the Arctic.

An Architect’s Artist

The sixth of seven children, Boberg was the daughter of Carin Nyström and the architect Fredrik Wilhelm Scholander. Her father was responsible for buildings such as the Stockholm Synagogue and the now former Royal Institute of Technology building in Stockholm. One of her sisters, Ellen, later married the Swedish painter Julius Kronberg. Little is otherwise known of Boberg’s childhood and upbringing.

In 1884, despite her mother’s initial hesitations (her father died in 1881), Boberg became engaged to, and later married, the architect Ferdinand Boberg. The latter was to become one of Sweden’s leading architects, responsible for a number of state-buildings, and private villas on Stockholm’s prestigious Djurgården. These included homes for artists, collectors, and members of the royal family, including Prince Eugen and Prince Carl, brothers to the then Crown Prince Gustaf. An infinite web of social and professional connections reveals itself in the Bobergs’ lives.

Married for over fifty years, the Bobergs never had any children. But a handwritten note added to Anna’s unpublished diaries, in the Royal Library of Sweden archives, recognised the importance of their marriage:

“You! My beloved, my enchanting, my adorable wife […] An infinite thank you for all you have been to me for nearly fifty years of unshakable unity.”

However, I digress. Enough about the men and society figures that appeared throughout Boberg’s life and who have arguably, although perhaps inadvertently, prevented her from attaining her own place in history.

Decorative Artist or Impressionist Painter

Without any formal artistic training, Boberg was only briefly enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris in 1884. Her exposure to the academy lifestyle popular among her colleagues was short-lived. A contemporary of the Swedish impressionist painters Eva Bonnier and Emma Löwstädt-Chadwick, who similarly attended the Académie Julian during the 1870s and early 1880s, Boberg was undoubtedly exposed to stylistic trends prevalent among her peers. We might assume from this that Boberg was at least familiar with the work of the impressionist painters, adopting an en plein air technique in her landscape paintings.

Boberg, alongside Bonnier and Löwstädt-Chadwick, among others, was also included in the Swedish display at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, a resounding success according the eminent art critic Royal Cortissoz. Here, Boberg had four works on display, including watercolours of Venice and a decorative folding screen. This penchant for the decorative continued throughout her life, and included tapestries, textiles, costume design, murals, and ceramics. By the time of the touring Exhibition of Contemporary Scandinavian Art held in the U.S. in 1912–13, Boberg’s art reflected the inspiration of the Lofoten landscape. Although she was the only woman whose work was on display, all seven exhibits were inspired by this Arctic environment and the Lofoten fishing community.

Postcards from around the World

The Bobergs travelled extensively throughout their marriage. In addition to a number of visits around the Mediterranean, including France, Spain, Italy, Greece, and Turkey, they also travelled to Jerusalem and Egypt in 1921. In 1926–27, the couple accompanied Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf (later Gustaf VI Adolf) and Lady Louise Mountbatten on a state visit to India. Boberg published an account of their experiences with Indian culture, religion, and architecture in Genom Indien i kronprinsparets fotspår (1928). Boberg also documented these travels visually, with paintings depicting the villas of Sorrento, Spoleto and Lake Como, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, views over Gethsemane and Palestine, the Dead Sea, and feluccas on the Nile.

Many of these paintings suggest a similar en plein air approach and climatically inspired palette as found in her Norwegian landscapes. Much remains to be said on these travels.

These visits all took place alongside a nationwide road-trip made by the Bobergs to document and visually record traditional Swedish architecture at risk of disappearing. Driving themselves around Sweden, travelling from south to north, they began their fragmented journey in 1916. They spread this journey over ten years. It resulted in a total of 3,050 graphite drawings, made primarily by Ferdinand. Boberg herself seems to have created very few drawings and sketches. Paintings of Sweden in her oeuvre are notably absent.

In Search of the Midnight Sun

The landscape of the Lofoten archipelago on the other hand, only 2,420 km south of the North Pole, offered Boberg a kaleidoscope of colour, light, and climates. Evoking the changes of the Arctic climate and seasons, Boberg found that a certain sense of freedom came from her visits to the Lofoten Islands. Frequently sending her husband back to Stockholm alone, she was so taken with this coastal environment that she sought to be left simply to paint, paint, paint.

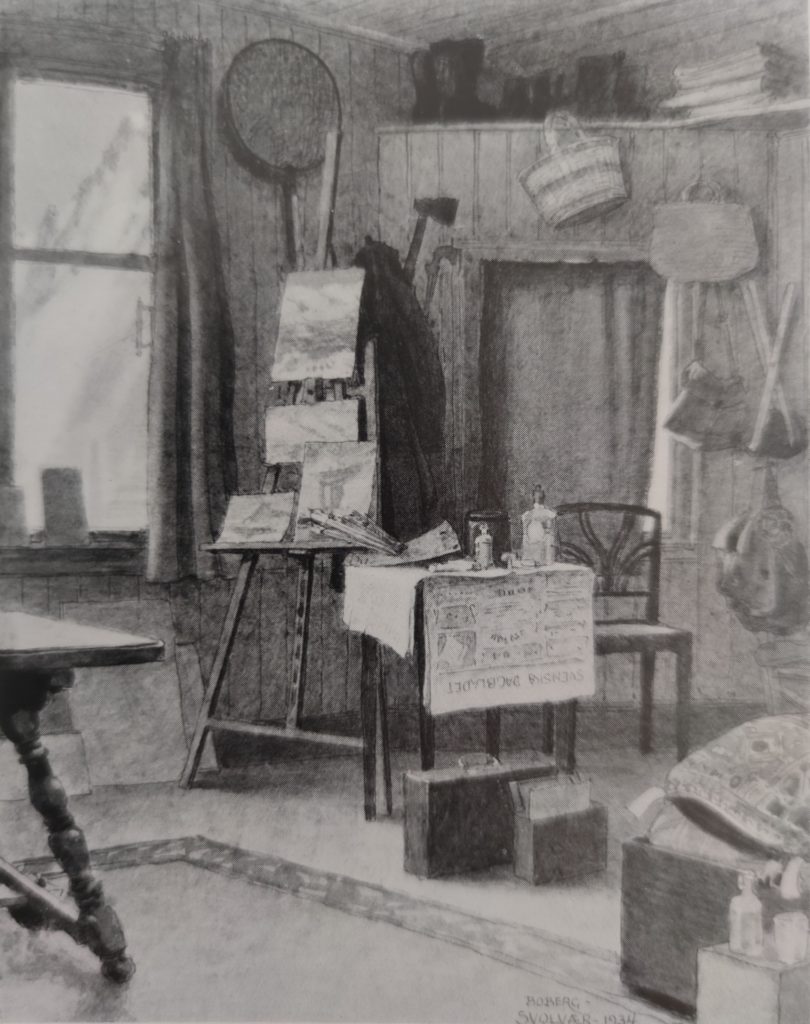

Insight into Boberg’s life on Svolvær might be found in a series of watercolour illustrations of their home on Fyrön (Kjeøya), carried out by Ferdinand in 1934, and included within Boberg’s autobiography. Of the exterior, descriptions provided by Boberg illustrate a little wooden house on a precipitous cliff, overlooking the mountainous harbour to one side and open sea to the other. Ferdinand’s studies give us an intimate insight into the home and lives the Bobergs created for themselves.

The husband assumes the domestic role. Throughout, artistic paraphernalia adorns the surfaces, and small sketches hang on the walls, while the Lofoten landscape remains a constant presence through the windows. The house was subsequently destroyed and replaced by a munitions bunker during the Second World War, later used for target practice by German soldiers.

Although Boberg’s studio lent itself to the creation of larger scale compositions of the surrounding landscape, many of her paintings are instead small, impasto sketches. Intimate studies such as Lofoten in Violet grapple with the effects of twilight and the processes of the Lofoten fisheries.

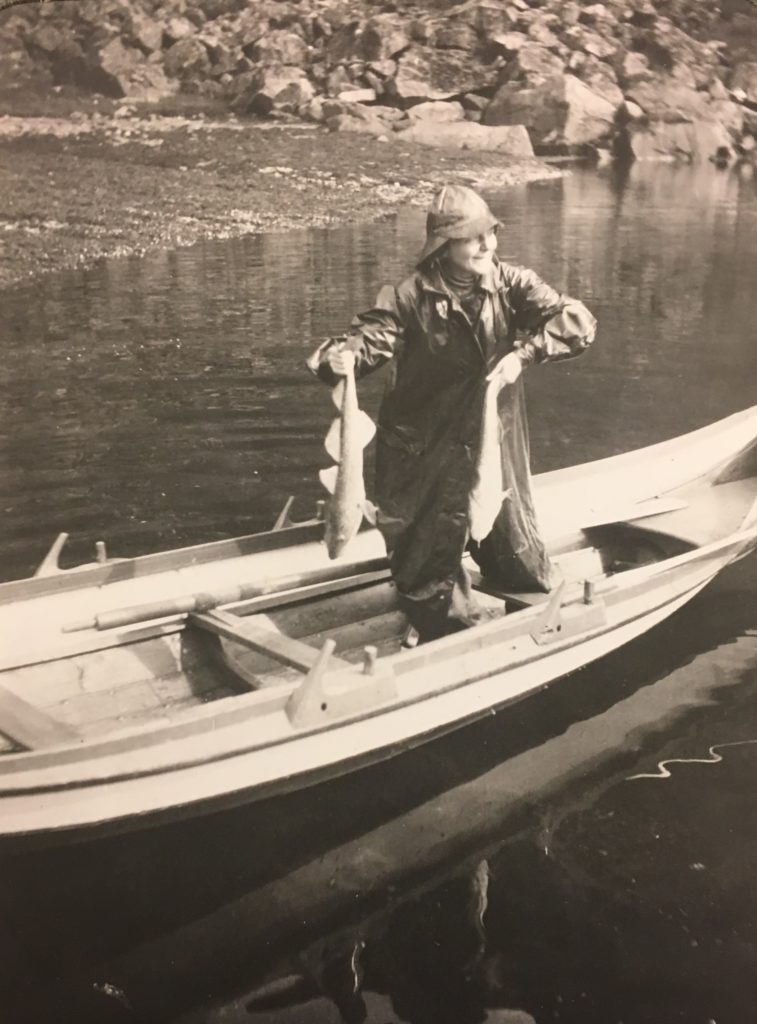

Often devoid of any human presence, they instead provide a method of engaging with the history, culture, and topography of the Arctic landscape. Boberg’s commitment to the Lofoten lifestyle and landscape also manifested itself in the purchasing of her own little boat, the Puttan. She managed this dinky vessel herself, which necessitated the invention of the portable easel seen in her fur-clad portrait.

A Frozen Fashion Faux-Pas?

As a white, Western woman working and living in the Arctic during the time of heightened interest in polar exploration and record making, Boberg offers an antidote to a male-focused Arctic narrative. The prevailing focus has been on the exploratory successes and failures of white settler colonial men from the Anglosphere. There is growing interest now in women and Indigenous communities around the Arctic. The staging of Boberg within the landscape dressed in her furs, conjures up the image of the intrepid explorer, akin to that of the Brit Robert Falcon Scott and Norwegian Roald Amundsen in their race to the South Pole in 1911–12. Contemporary photographs of Amundsen, for example, show the Norwegian explorer similarly dressed in his polar furs, and might inspire direct parallels between Boberg and contemporaneous polar exploration. Yet, despite the appearance of nutukas in Boberg’s polar wardrobe, the Sámi are notably absent from her photography and artwork.

Her seemingly radical independence appears to have raised eyebrows among some of her close friends, who in writing to her expressed their concern and apparent dismay over her chosen lifestyle and wardrobe. In letters from the French painter Georges Clairin and in another from the Parisian socialite Louise Garnier (wife of Charles Garnier, architect of the Paris Opera House), they both reference Boberg’s penchant for dressing in a fashion suited to the Arctic climate.

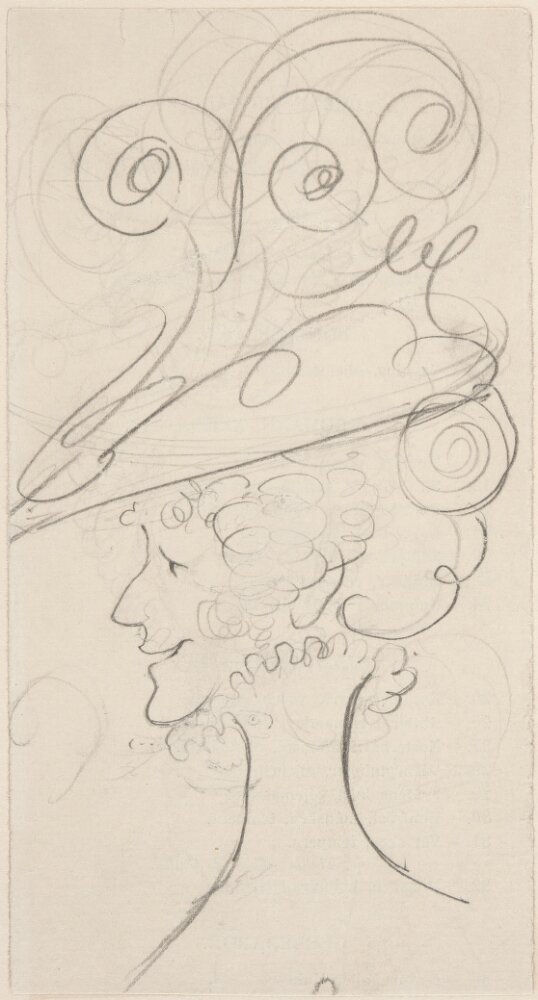

Drawing parallels between Boberg’s furs and those of the Inuit, they paint Boberg as a reckless woman far removed from civilisation. By contrast, an earlier caricature of Boberg made by the Swedish artist Carl Larsson in 1900 evokes a more Parisian fashion, resplendent with tightly bound curls and an elaborate hat. This is noticeably at odds with how Boberg fashioned herself while in the Arctic.

As we draw attention to the seemingly outlandish and radical character of Anna Boberg we might begin to rethink Nordic art history and help contribute to the growing scholarly interest in women artists, scientists, mountaineers, and explorers more broadly.

Dr Isabelle Gapp is an incoming Arts & Science Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto, starting October 2021. She holds a PhD in History of Art from the University of York. Her research considers the intersections between nineteenth- and twentieth-century landscape painting, gender and environmental history around the Circumpolar North. Follow her on Twitter.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattley

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Eunice Golden: Making Space for Female Eroticism in the Art Institution, by Isabel Gilmour

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by novelist Paula Butterfield

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

This is my first time looking at Anna Boberg’s oil paintings. They are magnetic and majestic. I can’t stop looking at such gorgeous art.

I also like her paintings, just been in Svolvaer today, but I just dont see, what living in a Lofoten fishing village has to do with polar exploration? “Only 2420 km south from the north pole” is not really around the corner. Even in 1920 I wouldn’t count the Lofoten Islands for “arctic”. Even though she is dressed for higher latitudes …