Guest post by Lisa Kirch, University of North Alabama

Introduction: Following Women Artists across the Year

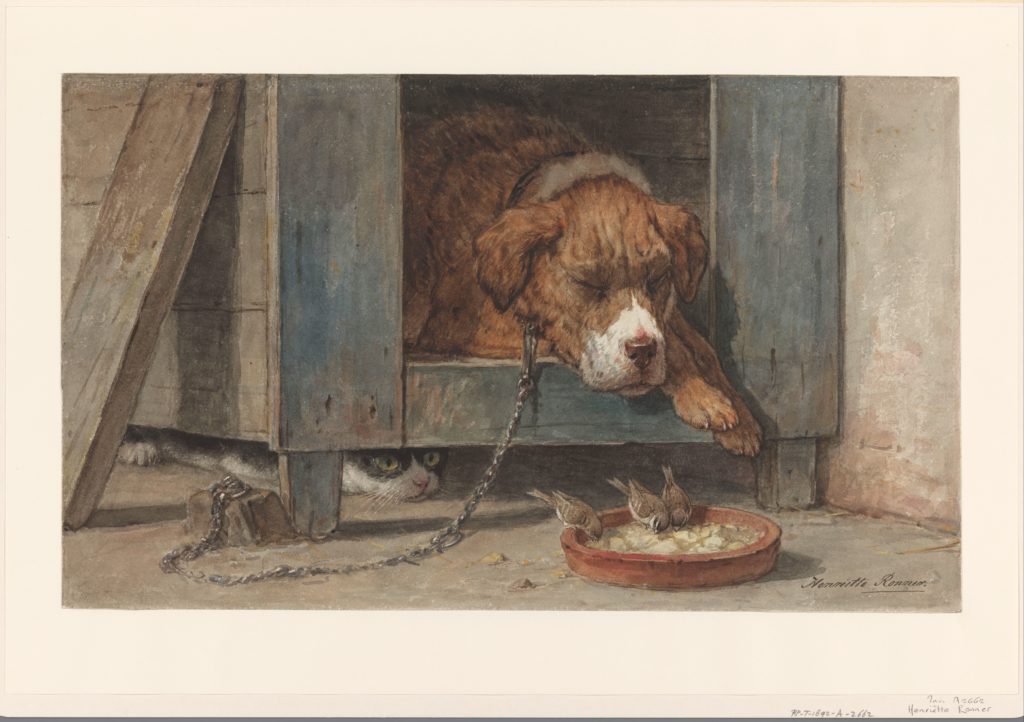

Its tip vermilion, a cigar glows in an ashtray. The smoker has stepped away for a moment, either forgetting or unaware that a kitten is in the room. Naturally, it is now playing with the dominoes strewn across the table-top. The kitten’s whiskers jut forward with excitement, as cat whiskers do, and it clutches its domino prey perilously close to that burning cigar. Domestic disaster is seconds away. The pencil will roll off the table. The dominoes and ashtray will fly. The cigar will burn a hole in whatever it lands on.

The painting is by Henriëtte Ronner-Knip (Dutch, 1821–1909), who piqued my curiosity nearly four years ago. In March 2017 I observed Women’s History Month with daily Facebook posts about women artists. The posts evolved from statements about a woman’s name, country of birth, and dates to a few lines about her life and work. By the time March ended, I knew there were too many artists born in other months for me to stop posting. Then, I envisioned a one-year project, but the 1400th posting day has just passed.

With few exceptions the posts mark a new woman’s date of birth, baptism, or death. The date comes from a list that I regularly add to. It ties each woman to the day when most readers will see the post. Using dates removes randomness and adds objectivity, even if choosing which woman to post hinges on less objective criteria. Centuries-dead or internationally little-known artists are preferable, since posting about them underlines how long and how globally women have been making art. Such posts also explode the common and mistaken notions that women rarely become artists and that we already know every woman artist who deserves attention.

Requiring a date can exclude an artist. Her records may be unpublished or lost; she may come from a culture that finds life dates unimportant. Security considerations cause many contemporary artists not to publicize their date of birth.

Despite drawbacks, the rule imposes few limits in practice. Posts concern women born between the fifteenth and twentieth centuries. The artists come from all continents but Antarctica. They work in every imaginable medium, producing fine art or commercial work; some hope to change the world with social or political messages. They are professionals and amateurs, trained and self-taught, and researching one woman generally leads to others. Families have passed down and fostered artistic talent for centuries. Women artists have taught other women, studied and traveled and lived together, corresponded with one another, and formed and joined professional organizations.

A Short Case Study

Starting with a date, a simple measure, widens perspectives by leading to out-of-the-way artists. Henriëtte Ronner-Knip offers a case in point. She was the best-known Dutch woman painter of her time, but, like me in 2017, readers of this blog may never have heard of her.

On her father’s side she was a third-generation artist. She belonged to the second generation of professional women in her family. Her aunt, Henriëtte Geertruida Knip (Dutch, 1783–1842), was a flower painter. Ronner-Knip’s mother may have been Pauline de Courcelles (French, 1781–1851), a bird painter mentioned in Ann Sylph’s guest post on this blog. Courcelles and Ronner-Knip’s father were married at the time of her birth but soon divorced. Three of Ronner-Knip’s children followed her into the profession and must have received their first lessons from their mother. Her painting supported the family, and when her husband died, their son took over managing her career.

Ronner-Knip probably drew on careful observation for Kitten’s Game (Dominoes). She would have posed her model in a special glass case—call it a catquarium—set up near her easel, but it might be more correct to say that Ronner-Knip’s lifelong study of animals produced the domino-playing kitten. The Rijksmuseum preserves sketches after her father’s work that she made at six years old.

They are good drawings for so young a child, and her father noted that she had made the first four “from memory.” This was a gifted child, and urgency sped her training. Her father was going blind and needed to teach while he still could. The best childhood drawings depict animals, and she finally settled on cats and kittens as her specialty. Stiff early compositions matured into painterly storytelling, its impact dependent on the artist’s accuracy in capturing feline facial expressions. Most paintings bear an unusually large, clear, prominent signature, ensuring their proper identification.

Ronner-Knip enjoyed international fame. Her career began in her teens and lasted nearly 70 prolific years. Contemporaries called her “great” and compared her favorably with Rosa Bonheur and Sir Edwin Landseer. Wealthy cat and dog owners commissioned pet portraits, and on both sides of the Atlantic many people knew her work in reproduction.

She seems to have maintained ties to a New York print publisher and gallerist for decades; his chromolithographs, less expensive than engravings, made her compositions available to a wide audience.

In the 1890s Ronner-Knip was the subject of books in Dutch, English, and French. A Dutch tulip breeder even named new fritillarias for her and a fellow native art luminary, Alma-Tadema. So enormous was Ronner-Knip’s celebrity that an anonymous author in the Detroit museum bulletin gushed about visiting her studio to purchase one of her “gems,” Kittens Musing, in 1904.

Less than 100 years later, the collection deaccessioned the work, now called The Best of Friends. In the Netherlands, the occasional exhibition or book testifies to the enduring pull of her best-known subject. So do the prices her work fetches at auction: £40,000 for a kitten at Sotheby’s in June 2020, €169,000 for a havoc-wreaking cat family at Christie’s in May 2009. While far from the price of a van Gogh, the sums are not exactly small change. However, as far as international art history is concerned, the painter has tumbled from fame into obscurity, a frequent fate for artists, especially women.

Toward a Clearer Overview

Art historians understand that working on forgotten women provides a chance to ask new, meaningful questions. How, for example, did Henriëtte Ronner-Knip’s experiences parallel or differ from those of other nineteenth-century women artists? She came to art in the time-honored way, by birth. For her, in contrast to her better-known contemporaries, the profession was not a choice that set a middle- or upper-class woman on a divergent path. Painting was expected, although Knip women did not specialize in landscape, as the men did. That is also food for thought, and further thought could go into examining the peculiar overlap between still life and Ronner-Knip’s cat paintings.

Such open-endedness characterizes my project. If Ronner-Knip and more than 1000 other women artists have taught me anything, it is that we are missing too much information to draw more than preliminary conclusions about women’s place in art. For all we’ve learned, we still have no real overview. We resist a canon that dictates worthy artists, works, media, and subjects, but then, we are aware of the canon and the problems it causes. We still unconsciously think within another canon, which encompasses only limited regions and periods of time. These do not include the nineteenth-century Netherlands. Indeed, they do not include much.

And so my Facebook readers stress their amazement at the sheer number and variety of women artists. Even art historians feel astonished. “What surprises me is how many Scandinavian women artists you feature—all of them talented and, to me, totally unknown,” wrote one. According to another, “I’ve also felt very chagrined by my own wondering, ‘How many can possibly be left!?’”

Knowledge gaps are closing more quickly than ever. Specialists’ English-language publications and dual-language exhibition catalogues make new research available to a global audience. Major exhibitions of women artists are increasingly international. We see their importance in the excited reception of Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862–1944) and Helene Schjerfbeck (Finnish, 1862–1946), admired at home but not elsewhere until recently. The crowds flocking to those and similar exhibitions further remind us that people in huge numbers already embrace the vibrant art history that work on women artists presents.

And Henriëtte Ronner-Knip? Keep an eye on May 31, 2021. That’s her bicentenary.

Dr. Lisa Kirch is professor of art history in the Department of Visual Arts and Design at the University of North Alabama. Her specialization is in German Renaissance visual and material culture. Patronage, collecting, and display are particular interests. Patrician women in sixteenth-century Frankfurt am Main and noblewomen in the houses of Wittelsbach and Hohenzollern have featured prominently in her recent publications. Her research has received support from the American Philosophical Society, the Renaissance Society of America, and Fulbright. She has taught courses on women artists since 2006. Readers interested in her calendar project may send her a friend request on Facebook.

Other Art Herstory blog posts about Dutch or Flemish women artists:

Anna Ancher’s Vaccination and Scientific Motherhood, by Alice Price

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Dr. Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Dr. Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

Anna Boberg: Artist, Wife, Polar Explorer, by Dr. Isabelle Gapp

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Dr. Katherine Manthorne

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Dr. Suzanne Scanlan

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by novelist Paula Butterfield

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge