Guest post by Maryse Dekker, student of art history, the University of Amsterdam

As the first female student of the Netherlands, Anna Maria van Schurman built quite a reputation as an intellectual in the seventeenth century. She knew multiple ancient and modern languages and published her own poems, essays and works of theology. Her work was recognized and praised by famous Dutch scholars. Eventually, her reputation expanded internationally. These intellectual achievements alone made her a remarkable woman. On top of that, she created art from all kinds of media. These artistic talents were admired by many, including queens. Anna Maria was an incredible all-rounder.

Education and Erudition

Anna Maria van Schurman was born in 1607 into a wealthy family. Because of her family’s financial security she could remain unmarried and devote her entire life to education and arts. Van Schurman’s education started early at home. She was able to read when she was only three. Through the classical education her father gave her, she learned Latin at the age of eleven. Since Latin was the “lingua franca” of science and education in Europe at the time, this language was essential to her further education. Her father also taught her other languages like German, English, Spanish, French and Hebrew. She continued her studies, mainly self-taught, after her father’s death in 1623. Anna Maria knew at least fourteen languages, which made her a phenomenal polyglot. Aside from learning languages, she had a great interest in theology, mathematics, and geography; and she studied the Bible intensively.

Through her family, Van Schurman became acquainted with the intellectual circles in the Netherlands, which stimulated her erudition even further. Famous scholars Constantijn Huygens and Jacob Cats, among other Dutch intellectuals, sent her books. They also sent letters in which they discussed a variety of topics, including history, scientific research, and political matters.

“The most learned woman of her time”

Between 1626 and 1636 she was member of “de Republiek der Letteren,” a European community of intellectuals. It was through this network that the impressive Van Schurman gained international fame and became known as “the most learned woman of her time.” Women were excluded from universities, but in 1636 something ground-breaking happened. With help from her neighbour, Professor Gisbertus Voetius, Van Schurman was permitted to attend lectures in literature, medicine and theology. She had to sit behind a curtain to avoid distracting the male students. This made her the first female student of the Netherlands and possibly even of Europe.

Feminist avant la lettre

In 1636 Anna Maria, as best Latinist in town, was asked to write a poem in honour of the opening of the University of Utrecht. She decided she would use this opportunity to point out the exclusion of women from universities.

But, you may ask, what is bothering you?

Well, these sacred halls are inaccessible to women!

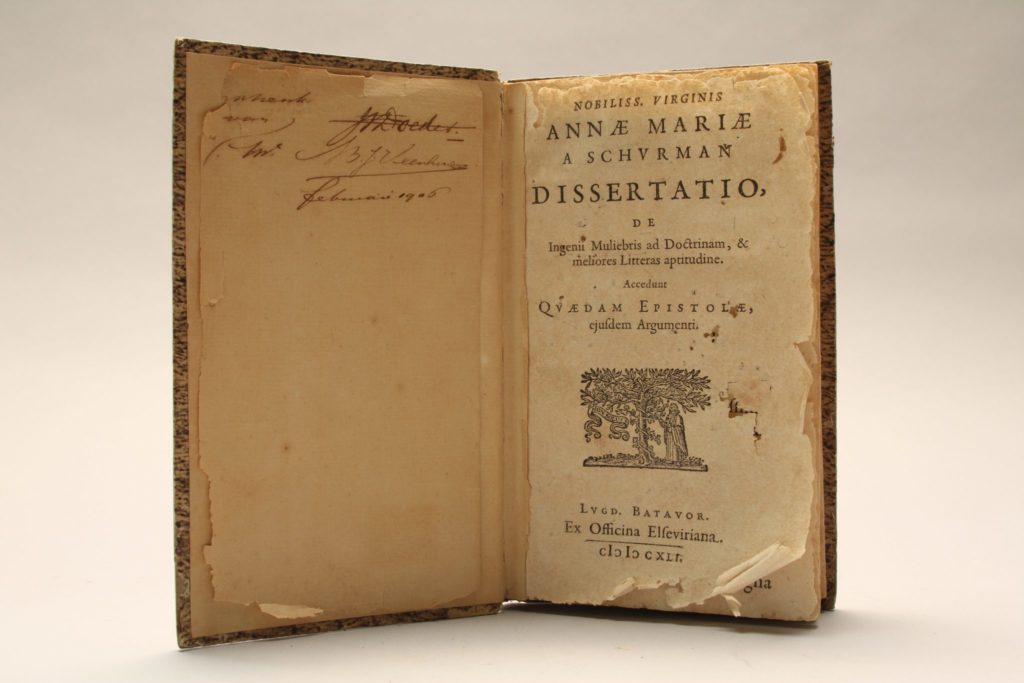

She strongly believed that women should have the opportunity to study, as long as it did not interfere with domestic duties. In her work Dissertatio de ingenii muliebris, published in 1641, she elaborated that it is appropriate for Christian women to study (Fig. 2). She radically challenged the belief that women are unfit for education.

The woman learns because she has the mental capacity.

This publication elicited many reactions and increased her fame considerably. Various educated women from Europe sought contact. They communicated by letter with Van Schurman as she encouraged them to study. Marie Jars du Gournay, Dorothea Moore, and Marie du Moulin are a few examples of the learned ladies she corresponded with. Van Schurman really was a “Feminist avant la letter,” and became inspiration for female learners. Simply by being a well-known female scholar, Van Schurman broke stereotypes of her sex.

“Virginum eruditarum decus”

Clearly, Van Schurman’s epistolary acquaintance and linguistic talent did not go unnoticed. People called her “the Dutch Minerva,” “the Star of Utrecht,” “the Tenth Muse,” etc. Many literary works were dedicated to her. Dutch scholar Jacob Cats also referred to her as “Virginum eruditarum decus” (Jewel of learned women). She constantly received flattering letters about her skills from around the globe. English poet James Martin called her a “miracle in the gentler sex.” French Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac, at the time the most influential epistolary writer, wrote: “One must admit that Mademoiselle de Schurman is a marvellous Girl, and that her Verses are not the least of her wonders.” It must have been her international fame that stimulated the demand for reprints and multiple translations of her work.

Trial and error: a self-taught artist

When she was not busy studying, Van Schurman practised the visual arts. Even though she never aspired to become a professional artist, her creations were unprecedented. Her artistic talent showed through at an early age.

Papercutting

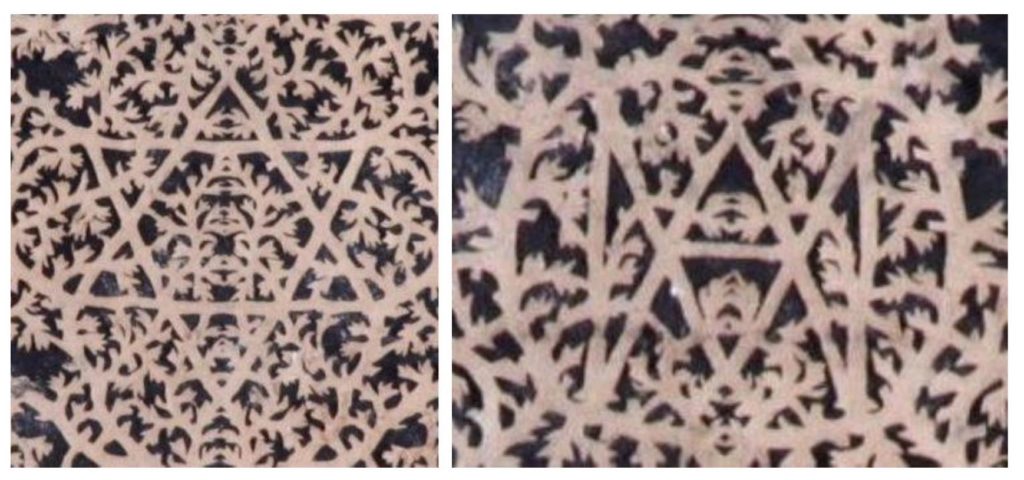

Barely six years old, she created incredible detailed paper cut-outs, which were sold for high prices. Unfortunately, not many of these cut-outs still remain. Fig. 3 shows one complex cut-out that did survive the test of time.

At the centre the Star of David is displayed. Integrated at the top and bottom is a monogram with the letters “AM. “

Embroidery

She did not stop at paper cutting. At the age of seven she taught herself embroidery, an elite woman’s activity. Many patterns used in the seventeenth-century were motifs of flowers, plants and animals, which Van Schurman also used in her work (Fig.4). Her enthusiasm for learning and experimenting only increased with age. In her book Dissertatio Van Schurman writes that she is mainly an autodidact.

Engraving on paper

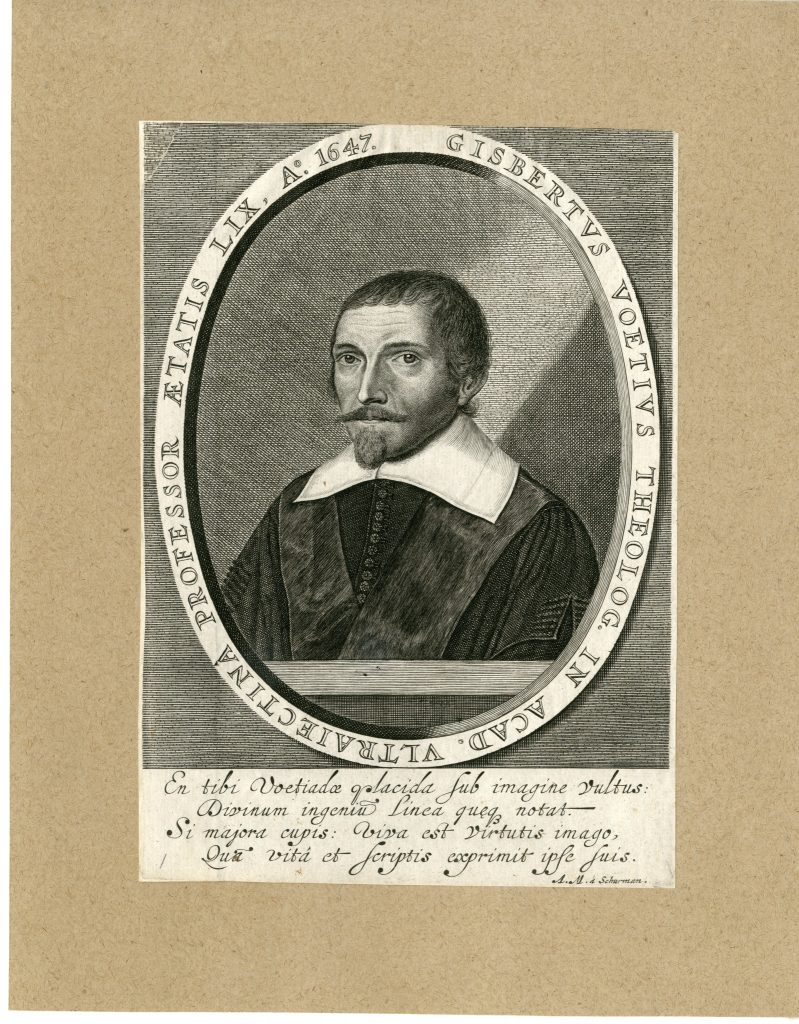

The only exception is the instruction in engraving she received in 1630s from Magdalena van de Passe, the daughter of the famous engraver Crispijn van de Passe. During her lifetime Van Schurman made portraits using a variety of mediums. Fig 5 shows an etching portrait of Professor Gisbertus Voetius. She often combined the techniques of engraving and etching, and she frequently included a Latin inscription at the bottom. Anna Maria created the illusion of spatial depth by shading and adding an oval frame, which pushes the figure to the back.

Pastel, oil painting, and other artistic mediums

Because of her constant experimenting, she became the first known artist in the Netherlands who made pastel portraits. In the image below Van Schurman depicted herself at the age of 33 (Fig. 6). She conveys liveliness in her face by using different chalks.

Van Schurman became skilled in other practices such as: oil painting (Fig. 7), painting in watercolors, wax modelling, and boxwood carving. Sadly, over the centuries most of her works have been lost. If the texts that discuss her artwork are to be believed, these lost works were of incredible value. For example, artist Gerard Honthorst estimated the value of a palmwood carving she made at a thousand guilders.

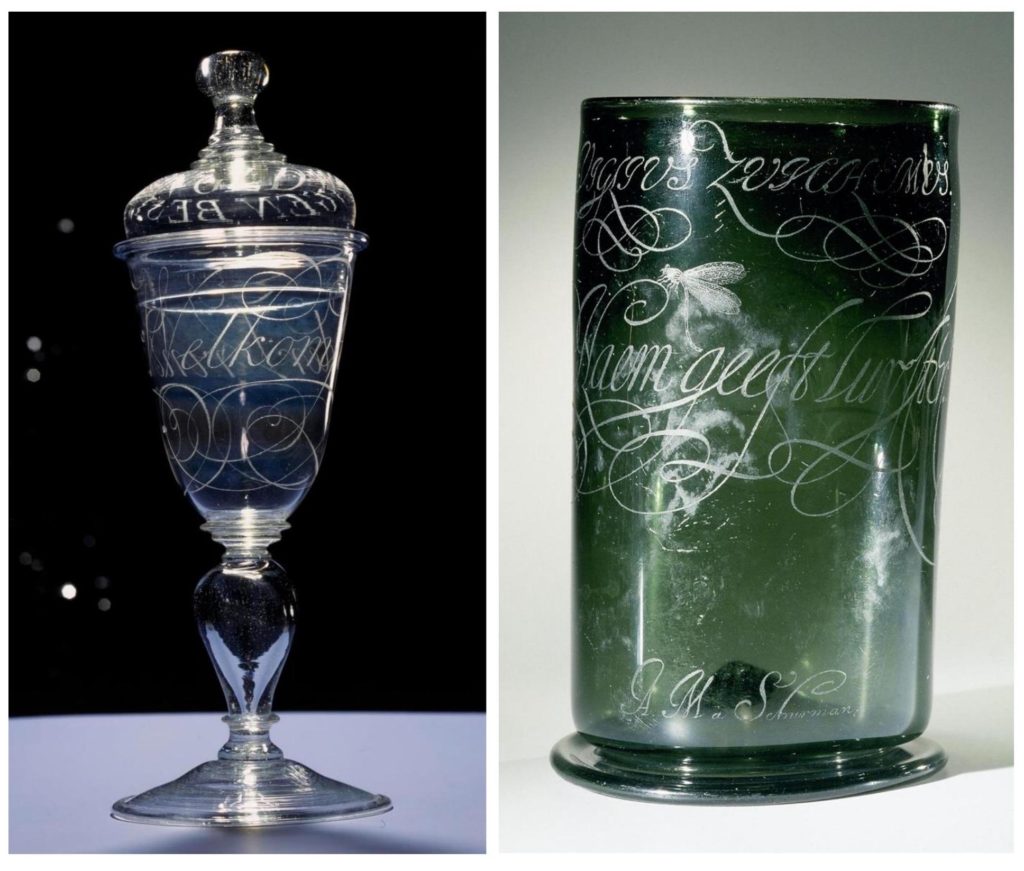

Engraving on glass

Another technique Van Schurman used is the diamond-on-glass technique. She created sophisticated calligraphy engravings, which often contained religious convention and moral sentiment. One goblet has the inscription “Welcome friends” on the glass and on the lid “Unforced best” (Fig. 8), meaning friendship should be simple and honest, rather than artificial. Another engraved beaker is inscribed with “Even though I shine darkly, / the Name gives luster” (Fig. 9). It is not clear what she means by this phrase.

Fig. 9. Anna Maria van Schurman, Glass engraving, ca. 1630–ca. 1670, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Even queens were impressed

In 1642 Van Schurman was admitted to the Utrecht’s St. Luke Guild of painters, which shows public recognition of her art. Aside from her contemporaries, who acknowledged her artistic talents and even called her “pearl of the canvas,” she also impressed several queens, for example Queen Christina of Sweden. In 1654 a group of men knocked on Van Schurman’s door, among them Christina, disguised in men’s clothing. Christina had heard about Van Schurman’s name [fame?] and decided to see for herself. The queen was astonished by how well-read Van Schurman was, and by her artistic talent. Polish Queen Ludwika Maria also paid her a visit. Given that even queens were impressed, it is clear that Anna Maria van Schurman was an extraordinary woman who left her mark on the world.

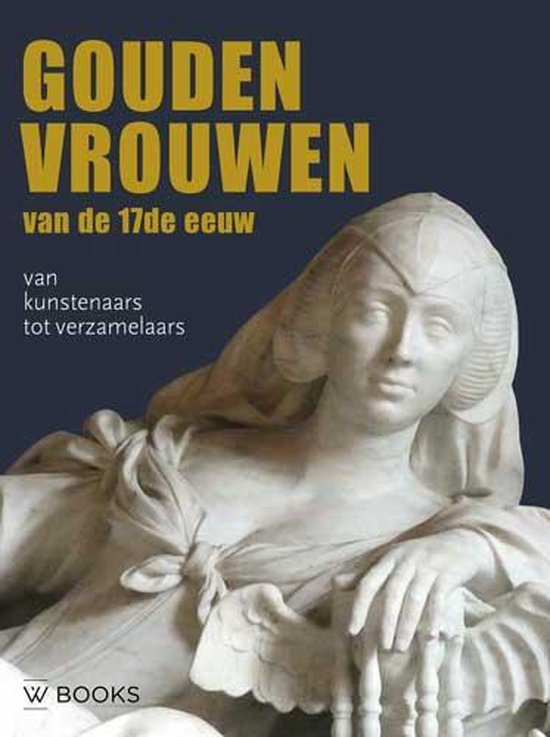

Maryse Dekker is an Art History bachelor student at the University of Amsterdam. She is one of the 34 bachelor students who contributed to the Dutch book Gouden vrouwen van de 17de eeuw: van kunstenaars tot verzamelaars (Golden Women of the 17th century: From Artists to Collectors), edited by Judith Noorman. The book tells the stories of 34 women in the Dutch 17th century who played an important role in the artworld. For a long time, they did not get the attention they deserve. This book aims to change the existing image of the art market as a male dominated world, by showing the significant role women played in the artworld as artists, dealers, collectors and patrons. Maryse contributed the chapter on Anna Maria van Schurman.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

The Rijksmuseum Opens Its “Gallery of Honor” to Women Artists

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Lisa Kirch

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur, by Nicole E. Cook

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

Trackbacks/Pingbacks