There also have been many experienced women in the field of painting who are still renowned in our time, and who could compete with men. Among them, one excels exceptionally, Judith Leyster, called “the true Leading star in art.”

—Theodore Schrevel, Harlemias, 1648

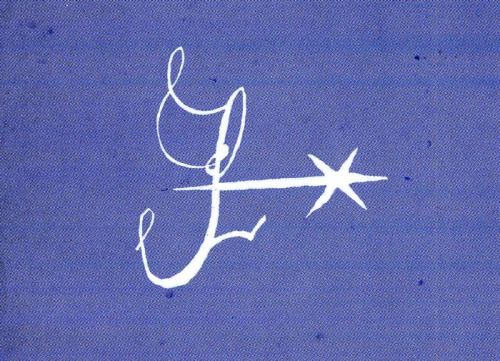

Four hundred ten years ago on this day, July 28, Judith Leyster (or Leijster) was baptized in Haarlem. Judith was the eighth child in her family. She went on to become, as Theodore Schrevel reported, “the true Leading star in art.” The name Leyster, which translates from Dutch as lode star or guide star, is a name the family adopted from the brewery that Judith’s father ran. The artist signed her paintings with a distinctive design that incorporates her initials with a star.

Judith and the Guild

It isn’t clear whether Judith Leyster or Sara van Baalbergen was the first woman to be accepted into the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke as a master painter. (Luke the Evangelist is the patron saint of artists, so his name is commonly associated with early modern European guilds for painters and other artists.) But it is generally accepted that Leyster was one of the first two women painters on canvas to become a member of the Guild.

Applicants were required to submit to a “master work” to the Guild as part of the application process. Scholars believe that Leyster submitted her self-portrait, a painting that for a couple of centuries was assumed to be a portrait by Frans Hals.

Once accepted into the Guild, Judith Leyster took on some male apprentices. When one of them left her, without the knowledge or permission of the Guild, to join the Frans Hals studio, Leyster took the case to court. The resulting settlement involved:

- the student’s mother paying four guilders to Leyster in punitive damages;

- Hals paying a three-guilder fine (he kept the apprentice); and

- Leyster herself paying a fine for not having registered the young man with the Guild in the first place.

Themes of Leyster’s paintings

Of her paintings that survive today, many are genre paintings of one to three figures, sometimes children, often engaged in games, musical performance or revelry of some other kind.

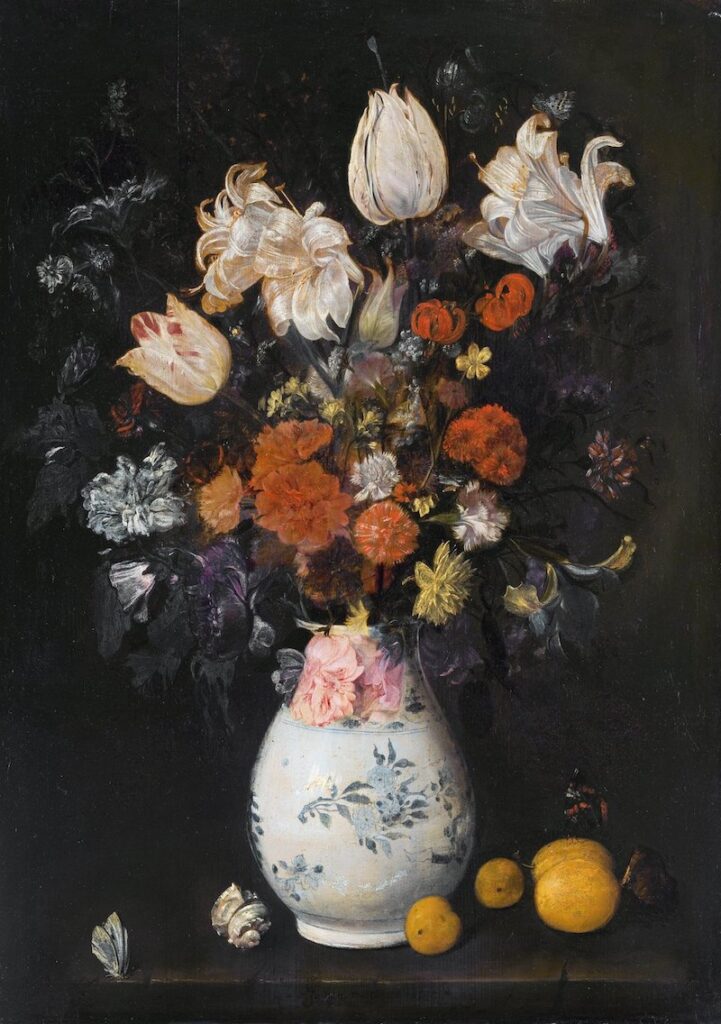

She also painted portraits and still lifes. Until the rediscovery of Blompotje about a decade ago (see below), Still Life with a Basket of Fruit was believed to be the only existing example of a Judith Leyster still life.

Later in her career …

The majority of Leyster’s known works were painted between 1629 and 1635, before she married the painter Jan Miense Molenaer in 1636. They had five children, two of whom survived into adulthood. Once she became a mother, she seems to have devoted much of her time to family and to managing her husband’s studio, rather than to painting. However, some paintings from the years after her marriage have recently come to light.

Leyster died in 1660, at the age of 50. But her story doesn’t end there.

An act of art fraud rescues Leyster from obscurity

For centuries, the artist’s entire oeuvre was misattributed. Some works were credited to Frans Hals. Others were attributed to her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer, possibly because after her death many of her paintings were inventoried as “the wife of Molenaer,” rather than as “Judith Leyster.”

While the initial misattribution of her works may have been largely accidental, there is at least one instance of deliberate deception. In 1893, an expert found Leyster’s distinctive signature mark on a painting sold to the Louvre: it was hidden under a false signature reading “Frans Hals.” The subsequent lawsuit was settled with a reimbursement to the museum of 25% of the purchase price.

Around this time, Cornelis Hofstede de Groot—the Dutch art historian who discovered the deception in the Louvre case—reattributed a half dozen other paintings to Judith Leyster.

New research leads to new discoveries

Fast-forward to the 1970s, when art historian Frima Fox Hofrichter took Leyster’s life and work as the topic of her dissertation. (See her reflections about the experience in her essay from Singular Women: Writing the Artist, edited by Kristen Frederickson and Sarah E. Webb, University of California Press, 2003.) Hofrichter later published the results of her thesis research in a book, Judith Leyster: A Woman Painter in Holland’s Golden Age (Davaco, 1989).

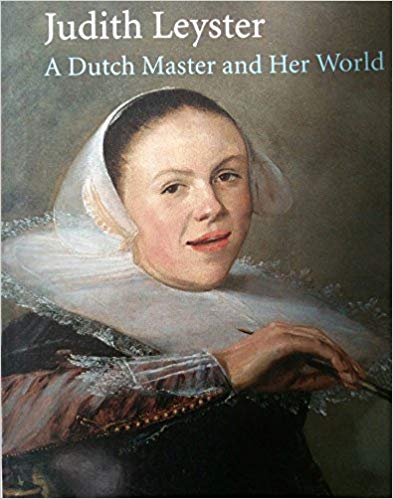

Following on from the groundbreaking work of Hofrichter and other art historians, in 1993 the Frans Hals Museum and the Worcester Art Museum presented the exhibition “Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World.”

In 2009, in honor of the four hundredth anniversary of the birth of the artist, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem hosted “Judith Leyster, 1609-1660.” In the same year, coinciding with the Hals Museum iteration of the exhibition, a Belgian collector alerted the museum to a Leyster work in her possession, which had never before been publicly displayed. Anna Tummers, curator of Old Masters at the museum, authenticated the work as a flower still life signed “Judith. molenaers 1654.” Experts had known of this work, since it is documented in the inventory of possessions of Leyster’s husband when he died in 1668. But it had long been assumed lost.

Just a few years ago, in 2016, a later Leyster self-portrait came to light. Experts from the auction firm Christie’s had been hired to evaluate the contents of an English country estate. There they discovered this long-lost treasure, hiding in plain sight—the owners had no idea of its value and historical significance. According to an article in Artnet News, it sold at auction for nearly $600,000.

In November 2018, Judith Leyster herself turned up in an unexpected place—as a protagonist in a work of historical fiction. A Light of Her Own, by Carrie Callaghan, was deemed by Publishers Weekly to be “a riveting debut,” and the Washington Independent Review of Books selected the novel as one of its “Favorite Books of 2018.” Read Art Herstory’s interview with the author here.

To date, some 35 surviving paintings have been identified as Judith Leyster’s work. It is difficult to present an exact count, since in some cases the attribution is still contested. These works can be found today in museums and private collections in (at least) Holland, the United States, Britain, Italy, Sweden, France, Germany, Norway, and Italy.

With luck, the coming years will bring new discoveries about Leyster, as art historians, dealers, and other cultural professionals continue their work of restoring this female Old Master to her rightful place of honor in the art historical record.

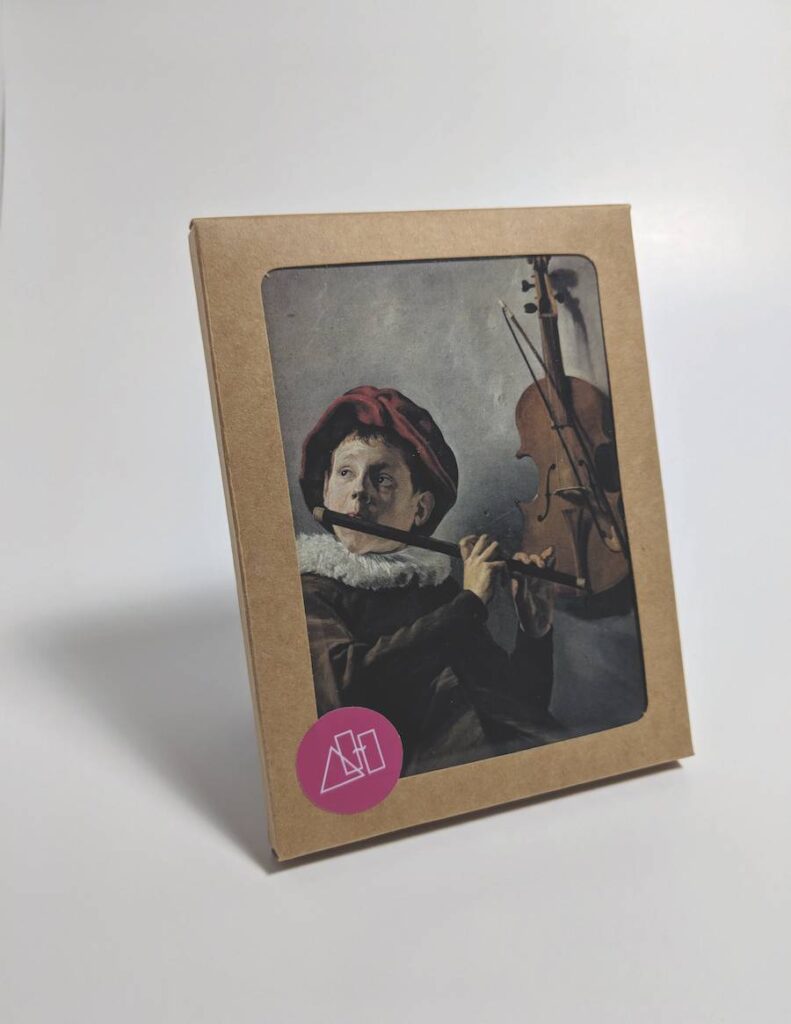

As of December 2019, Judith Leyster’s Boy Playing the Flute, 1630s, is included in the CODART Canon as one of 100 Dutch/Flemish masterpieces (per a vote by CODART curator-members). The original is held at Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, Sweden. The painting is reproduced on an Art Herstory note card. For more information about this card and one other that reproduces a Leyster work, visit the Art Herstory Shop. See also the Art Herstory Judith Leyster resource page.

More about Dutch or Flemish Women Artists:

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist (Guest post by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy)

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis (Guest post by Dr. Quentin Buvelot)

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch (Guest post by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols)

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur (Guest post by Dr. Nicole E. Cook)

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): A Birthday Post

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

More Art Herstory blog posts:

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

An Interview with Carrie Callaghan, Author of “A Light of Her Own”

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists (Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew (Guest post by Dr. Laura Gowing)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

An Interview with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint” (BWP is a novel-in-verse featuring Artemisia Gentileschi as protagonist)

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

Trackbacks/Pingbacks