Guest post by Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks,

Distinguished Professor Emerita of History and Women’s and Gender Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

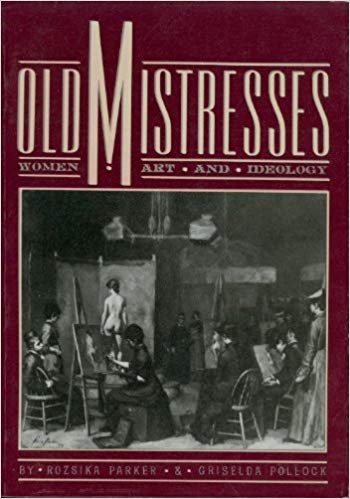

A decade after Linda Nochlin posed her irreverent and provocative question, “Why are there no great women artists?” (Art News [January, 1971]) Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock published Old Mistresses: Women, Art, and Ideology (New York, 1981), addressing the processes through which women’s art came to be separated from the category of “art” and seen as an expression of femininity. Picking up on Nochlin’s key idea, they looked at the masculinization of the category “artist,” and the ways in which everything that detracted from “greatness” in art was coded feminine.

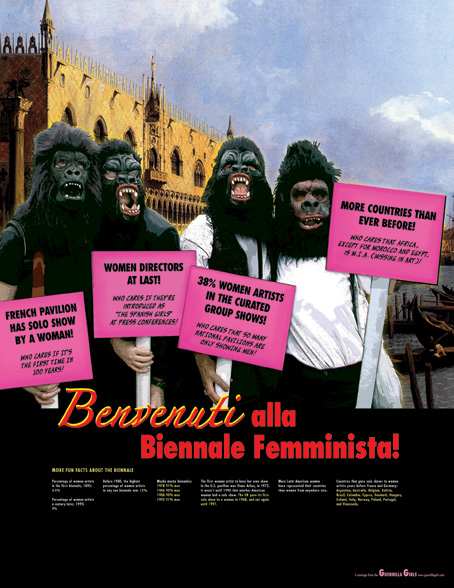

Their book was part of a huge effort on the part of feminist art historians that began in the 1970s to uncover, document, and analyze the lives and work of ignored or forgotten women artists, and to examine (and critique) gendered artistic production and visual representation more broadly. The result was a series of exhibitions, exhibition catalogues, articles, and books, parallel to the explosion of work by contemporary artists engaged in feminist inquiry. (Which then itself became the subject of analysis.) By every standard of measurement—solo exhibits in commercial galleries, major exhibits in museums, curated group shows, monographs—the work of historical and contemporary women artists was receiving increasing recognition. According to Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, and Nancy Pricenthal in After the Revolution: The Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art (2007), the number of women with solo exhibitions at commercial galleries rose steadily into the 1990s, reaching about 24 percent. Even H.W. Janson’s History of Art was forced to change; the 1986 edition added nineteen women along with its 2,300 male artists. (Though by that point H.W. Janson himself was dead and the additions were made by his son.) The 2005 Venice Biennale was headed by two women directors, Maria de Corral and Rosa Martinez, and 38 percent of curated group shows in it were works by women artists. Unsurprisingly, this was dubbed “the feminist Biennale.”

“Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: Portfolio 2”).

National Museum of Women in the Arts, ©Guerrilla Girls.

“A Feminist Consummation That Did Not Happen”

Well, you can guess what I’m going to say next, because you know what happens with triumphant trajectories like this one. Post-2016 we all live, as Penelope Anderson and Whitney Sperrazza put it, “in the wake…of a feminist consummation that did not happen,” a feminist future did not come to pass. (Penelope Anderson and Whitney Sperrazza, “Feminist Queer Temporalities in Amelia Lanyer and Lucy Hutchinson,” in Gendered Temporalities in the Early Modern World [Amsterdam, 2018]). Often in the same article praising the 2005 Venice Biennale for its inclusion of women, the two directors were described as the “Spanish girls.” In the first decade of the twenty-first century women’s share of solo exhibitions at commercial galleries dropped to 21.5 percent, though women earned more than half of MFAs. The number of monographs about women artists, past and present, remains much lower than those about men, as is the price for their work. Now there is a National Museum for Women in the Arts, but other than special exhibitions, the other major art museums remain Museums for Men in the Arts. At the 2005 Venice Biennale, the indefatigable Guerrilla Girls counted all the works at six of Venice’s major museums; they found that of the roughly 1240 works, 40 were by women. A bit better than Janson in 1986, but not much.

That count is one of the reasons that Old Mistresses matter today. Despite decades of fabulous feminist art history and fabulous work by contemporary women artists, the categories of “great” and “major” art, and of “eminent” and “excellent” artists defined by Giorgio Vasari back before the Old Masters were old still structure how art is displayed and valued. Women artists have almost no name recognition, even for periods in which at least a few men artists are household names. Vasari did include a handful of women in Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550; 1568), for as Pollock and Parker explain, only in the twentieth century did women artists disappear from art history. But most museum goers today have no idea that one of the women Vasari included—Sofonisba Anguissola—was a painter in the court of Philip II of Spain for fourteen years, and on returning to Italy, received commissions and taught younger artists throughout her long life. She painted one of her last self-portraits when she was nearly 80, and when she was 92, the Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck came to talk with her about painting.

Held at the Gottfried Keller Foundation, Bern;

image source, Wikimedia Commons.

Fans of the Ninja Turtles (now often parents of young children themselves) have no idea that when their creator decided to introduce a female character to go along with Donatello, Raphael, Leonardo, and Michaelangelo (sic), he COULD have named her Sofonisba, but instead chose the only familiar female name in Renaissance art, Mona Lisa. (She was a lizard; she didn’t last long.) So we need to keep saying (loudly and often), yes, there were female Old Masters, more than we knew of in the 70s and 80s, and we should keep looking for and looking at their work, because it’s wonderful. Their contemporaries recognized this, and we benighted moderns should, too.

Held at the National Gallery, London.

But there’s another reason. In re-reading Old Mistresses recently—which was re-published in 2013, BTW, with a new preface by Griselda Pollock—I was struck by how much the issues the authors raise apply to women’s art in any period and are still with us. To give just one: if a female artist uses conventional or stereotypical imagery, is she reinforcing sexist and hierarchical cultural attititudes or could she be subverting them? You can ask that about any self-portrait of a woman artist, from those in medieval manuscripts to ones made yesterday. You can ask that about women who painted flowers, whether she was Rachel Ruysch or Georgia O’Keeffe. You can ask that about women whose figures are delicate or pretty, whether she was a Ming court artist, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, or Kara Walker. You can ask that about women who painted religious figures, whether she was Sister Plautilla Nelli or Alma Lopez. The answer won’t be the same, of course, and we won’t all agree. (Nochlin’s answer was different, in fact, than Parker and Pollock’s.) But a failure to take female Old Masters into account leaves us with a short view, which impoverishes the question and limits our understanding.

Renaissancesociety.org.

Professor Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks is Distinguished Professor Emerita of History and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is an author or editor of more than thirty books and more than 100 articles that have appeared in English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Chinese, Turkish, and Korean. Her books include Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe (now in its 4th edition), Gender in History: Global Perspectives (now in its 2nd edition), and A Companion to Gender History (co-editor with Teresa A. Meade; 2nd edition forthcoming in 2020). Her research has been supported by grants from the Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, among others.

More Art Herstory blog posts:

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? (Guest post by Dr. Sheila ffolliott)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Dr. Sheila Barker)

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur (Guest post by Dr. Nicole E. Cook)

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest Post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): A Birthday Post

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Thank you! Much needed–and I may just assign this to my students…

Thanks so much for this great article. You’re helping shine a light on the true history of art, which includes so many talented women. I write a historical fiction series about a Renaissance-era female artist and the scholar on her trail, so I’ve done a lot of research on the topic, but I haven’t yet read Old Mistresses—it’s on my list now!

It’s been a long time coming ( as the song goes I own and love my old mistress painting. Will decide on which American museum to loan it to soon