Women Artists and Their Contended Place in Public History

Guest post by Sheila Barker, The Medici Archive Project

This essay is a pendant post of Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet?, by Sheila ffolliott.

Exhibitions as Feminist Activism

There is a long history of women artists around the world organizing their own exhibitions in response to exclusion from the institutional Academies and Salons. However, something new was afoot in the United States in the 1970s, when advocates of women’s art began to adopt the tools of activism, from public protests to high-profile lawsuits. Although the power structures that marginalized women were still in place, women in the art world were beginning to radicalize. In 1970, Lucy Lippard organized the “Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists.” The “Women in the Arts Foundation” formed in 1971, the same year that Linda Nochlin published her landmark article “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

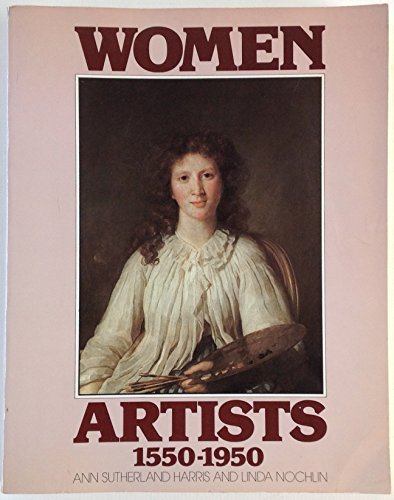

Inspired by Nochlin’s article, two curators at the Walters Art Museum, Ann Gabhart and Elizabeth Broun, expeditiously drew up a checklist of 35 female artists in their museum’s own collection. Their exhibition, “Old Mistresses: Women Artists of the Past,” opened and closed in 1971. Although it achieved a milestone, it left little trace other than a brief essay in the museum’s journal, followed by a checklist. Five years later, a breakthrough exhibition of ponderous dimensions nearly obliterated the memory of “Old Mistresses.” Curated by Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris, “Women Artists, 1550–1950” opened in 1976 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with 150 artworks by 83 women artists, including six major works by Artemisia Gentileschi. It was a mediatic and financial success. More than 140,000 people saw it before it continued to Austin, Pittsburgh, and Brooklyn.

In the introduction to the hefty, richly illustrated exhibition catalog for “Women Artists, 1550–1950,” the curators explained their goals carefully, not only to neutralize their misogynist opponents, but also to reconcile their position with a widely divergent range of feminist thinkers. According to Linda Nochlin, “the purpose of the exhibition was to show that women have participated significantly in Western art, and to establish at the same time, that there is no perceptible difference in style, subject or technique between the male and the female artist…no mysterious essence of femininity.” In a 2012 interview, Nochlin said she and Harris were not seeking to prove that women artists had achieved greatness, but just to show “what women as artists had done.”

Feminist Opposition to an Exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi

The success of “Women Artists, 1550–1950” belied the fact that it was born from bitter legal battles between feminist activists and the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art. In 1970, exasperated by the exclusion of contemporary women artists from LACMA’s exhibitions, the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists threatened to file a lawsuit with the Civil Rights Commission and brought in an all-female legal team from the American Civil Liberties Union. A truce was reached when Museum Director Kenneth Donahue offered to allow a monographic show on an Old Master woman artist he admired: Artemisia Gentileschi. Donahue’s colleague Ann Sutherland Harris instead recommended a large all-woman exhibition. When Donahue made her the curator, Harris called on Linda Nochlin to oversee the modern material.

For some of the activist members of Los Angeles’ Feminist Art movement, Harris’ and Nochlin’s exhibition represented a disheartening compromise with LACMA and a failure to achieve their long-term goals. This sentiment is understandable. But what comes as a surprise, perhaps, is that both the activists and Ann Sutherland Harris alike strongly objected to Donahue’s original suggestion of a focus show on Artemisia Gentileschi.

For many feminists of that period, the problem with Artemisia was that conservatives such as Kenneth Donahue liked her art. As a widely respected Old Master, Artemisia fit in all too well with the masculinist patriarchy’s narrowly defined category of great art, and thus Artemisia wasn’t radical enough for some feminists. In their view, a celebration of Artemisia’s art didn’t call into question the paradigms by which most women artists had been excluded from the conversation. Freighting matters all the more, Artemisia’s success as an Old Master threatened to undermine the efforts of some women artists and feminist critics in the 1970s to define the style of women’s art against the style of men’s art, and to define male aesthetics as separate from female aesthetics.

All-Woman Exhibitions: Ghettoization or Globalization?

Already at the time of the “Women Artists, 1550–1950” exhibition, some feminist art historians doubted the benefits of an all-woman exhibition. Mary Garrard was one of them. Her review of “Women Artists, 1550–1950,” published in the July 1977 issue of The Burlington Magazine, concluded: “Now that [these artists] have been displayed as women, it is time to shift the emphasis and to examine their achievement as artists, shaped by a variety of personal experiences, not the least nor the most of which was being born female.” Ann Sutherland Harris in fact agreed with Garrard about the problem of all-woman exhibitions. In her 1976 catalog she wrote that the exhibition was not a model to be repeated over and over, but rather a means of turning the page so as to “remove once and for all the justification for any future exhibitions with this theme” (Harris and Nochlin 1976, p. 44). Yet Harris’ expectation that this exhibition could serve as a definitive watershed overlooked the fact that it had excluded women who practiced outside the Western tradition.

Those geographic blinders came off in 1988 thanks to two exhibitions dedicated to the early women artists of Asia. At the University of Kansas’ Spencer Museum, the exhibition “Japanese Women Artists 1600–1900” opened in the spring, curated by Patricia Fister. The Indianapolis Museum of Art’s “Views from the Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists 1300–1912,” which opened that autumn, counts as the world’s first exhibition on Chinese women artists. Both exhibition catalogues attended to the social history of women as well as to traditional connoisseurship practices, with Fister arguing against the theory of an inherent feminine style.

It’s Becoming Okay to Have an Agenda

Many exhibitions on individual and collective female Old Masters followed. The first of a long line of exhibitions dedicated to Artemisia Gentileschi took place in 1991 at Florence’s Casa Buonarroti Museum. Two art historians specialized in the connoisseurship of Italian seventeenth-century painting, Roberto Contini and Gianni Papi, curated this show, entitled simply “Artemisia.” Their attributions proceeded without regard to Artemisia’s gender; however, the exhibition itself was not a gender-neutral event. It came about because of the determination of the Director of Casa Buonarroti: Pina Ragionieri, one of Italy’s first female museum directors.

More recently, curators of exhibitions dedicated to female Old Masters have begun to wear their feminism on their sleeve. They have discovered that supporting a larger social agenda can be a potent vehicle for connecting with wider publics and making Old Master art relevant to younger generations. Curated by Alejandro Vergara, the Prado Museum’s 2016–2017 exhibition on Clara Peeters gained worldwide attention as the first large-scale monographic show dedicated to this artist, as well as the Prado Museum’s first exhibition dedicated to a woman. The show observed the highest scholarly standards, yet at the same time it firmly aligned itself with the goals of equality and social justice, just as the Me Too movement exploded on social media sites.

The Uffizi had dedicated its first show to women artists several years earlier, in 2010, with Giovanna Giusti’s “Autoritratte. Artiste di Capriccioso e Destrissimo Ingegno.” The exhibition treated the gender element rather gingerly, embedding it within the history of Medici collecting. In her foreword to the catalogue, Cristina Acidini, Superintendent of Florence’s Polo Museale, echoed this ambivalence towards feminist art history, indicating that she took pride in seeing the collection of women’s self-portraits despite her “scant sympathy for issues of gender” (“a dispeto della mia poca simpatia per ‘questioni di genere’”). Appointed Director of the Uffizi in 2015, Eike Schmidt ushered in a new era. Inspired by a visit from Frida Kahlo of the Guerilla Girls, he pledged to mount two shows on women artists annually. Jane Fortune (1942–2018), founder of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation, helped Schmidt fulfil his goals by underwriting the restoration of women’s works in the museum’s collections.

Thinking Outside the Box About Women’s Art Inside the Museum

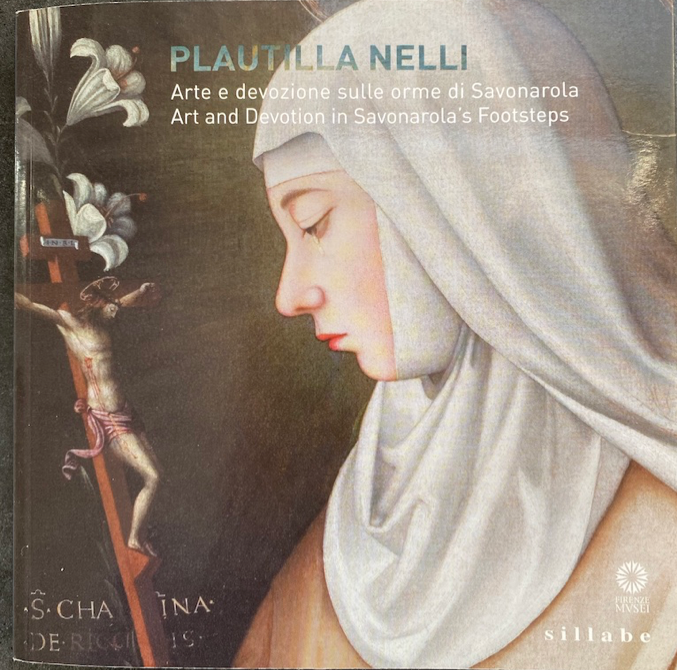

The first fruits of Eike Schmidt’s commitment to women artists appeared in 2017 with an exhibition dedicated to a nun artist: “Plautilla Nelli. Art and Devotion in Savonarola’s Footsteps,” curated by Fausta Navarro. Navarro’s exhibition took a radical step forward. Rather than taking the traditional connoisseurship approach with comparisons to other Old Masters, or even the straightforward monographic approach, Navarro instead enveloped Plautilla in religious and social history, and brought out all the contradictions of evaluating a nun artist according to a conventional art historical framework.

Navarro installed Plautilla’s works among many humbler ones made by anonymous convent collectives. These included a textile altar frontal; painted copies; a devotional seal made with a needle, paper, and blood; a Christ doll; and a small rustic devotional image with papier-mâche flowers. In its exquisite weirdness, this small exhibition set off a quiet revolution with its total rejection of the aesthetic values of patriarchal art history.

Conclusion

What can we take away from this brief overview? First of all, while there is no single right way to design exhibitions around early modern women artists, there are certain pitfalls that should always be avoided. One of them is the museum’s institutionalizing effect upon women’s art. In 2016, Ruth Iskin warned that exhibitions neutralize the power of women’s art when they focus solely on connoisseurship, sidestepping the issue of gender. Navarro’s innovative exhibition of the works of a nun artist among those of her anonymous sisters pointed to one way out of this impasse. The Prado’s 2019/2020 exhibition A Tale of Two Women Painters: Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, curated by Letizia Ruiz Gómez, offered another solution by situating the show’s two protagonists in the broader context of gifted women artists whose paintings document their own emergent self-awareness.

Just as early modern women artists broke away from the conventions of their times, so can the exhibitions we dedicate to them. Perhaps a sense of disjunction will always linger when women are put on display in hoary institutions largely designed to celebrate a patriarchal view of art history, but that should not dissuade us. Every time we hang the work of a female Old Master on a museum wall, we give women and girls a greater knowledge of their own history, as well as a chance to write it anew.

Dr. Sheila Barker is the Founding Director of the Jane Fortune Research Program at the Medici Archive Project in Florence. She has published numerous articles, two books (Artemisia Gentileschi in a Changing Light and Women Artists in Early Modern Italy), as well as an edited journal issue for Memorie Domenicane (Women Artists in the Cloister / Artiste nel chiostro). Among her forthcoming publications is a volume about Artemisia Gentileschi, which will appear in the book series Illuminating Women Artists, published by Lund Humphries (Barker also serves on the series editorial board). Her spring 2020 exhibition, ‘The Immensity of the Universe’ in the Art of Giovanna Garzoni at Palazzo Pitti in Florence, has been postponed due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? (Guest post by Dr. Sheila ffolliott)

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration (Guest post by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque