Guest post by Sheila ffolliott, Professor Emerita of Art History, George Mason University

This post follows upon Merry Wiesner-Hanks’ guest piece Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? posted here on 21 April 2019. It is also a pendant post of The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters, by Sheila Barker.

Dropping the gauntlet

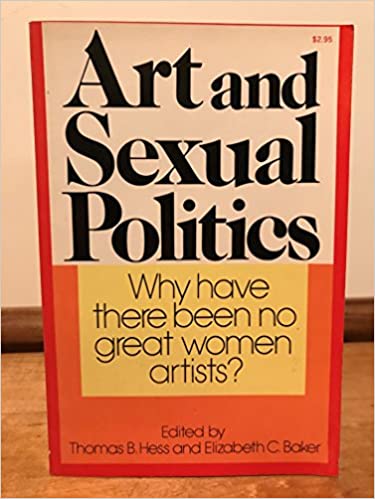

Linda Nochlin published “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” almost fifty years ago, in 1971.

Nochlin admonished against arguments for including women artists who deserve to be called “great” within the existing historical and critical framework. Instead, she queried the determinants informing the definition of “greatness,” concluding that conditions affecting women’s lives and training—compounded by the priorities and practices of art history, art criticism, the art market, and many museums—have kept women at the margins.

In a talk delivered at the Prado as part of a conference held January 27–28, 2020 in conjunction with the exhibition on Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana, I tried to reassess the issue of “greatness” with regard to women by applying Nochlin’s thesis to the Renaissance-Baroque period. My talk could not address them all, so I chose some topics that inform how greatness was and is defined as it pertains to early modern women artists by pointing out some avenues to explore

- the selection of works that populate museums and art history books;

- the art market: how much people will pay as an index of value in broader terms;

- the purposes that what we now gather together within the term “art” served in different historic eras; and

- the gendered language prevalent in art criticism.

To start, I asked, how did Nochlin come to this question? She graduated in 1951 from, and later taught Art History at, Vassar, then a women’s college. (Full disclosure: I had the good fortune to be her student as an undergraduate.) In this 1959 photograph she leads a discussion as part of the introductory survey course.

From the classroom to the museum

In 1969 Nochlin offered a seminar, The Image of Women in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Her description of the topics to be covered acknowledged how this was new territory, and how it would involve working from disciplines outside art history (Nochlin “Starting from Scratch: The Beginnings of a Feminist Art History,” in Broude and Garrard, The Power of Feminist Art, New York 1994, 130-139). The setting at Vassar was significant: there was no éminence grise to tell her she couldn’t offer something this radical, and it led to her pathbreaking essay.

Linda’s bold new assertions led a French university to highlight her and her approach on a licence exam.

Which aspects of Nochlin’s essay help us ponder the question of “greatness” for females of the early modern era? We know about the social norms regulating women’s behavior, but how have art history, art criticism, the art market, and institutional practices affected women artists’ production and reception?

Getting to the point

The issue of greatness starts with the definition of art. Nochlin’s characterization of the Romantic myth that “art is the direct, personal expression of individual emotional experience, a translation of personal life into visual terms” was never the purpose of art in the early modern era. Martin Warnke (The Court Artist: On the Ancestry of the Modern Artist) argued that such a notion does not mesh with those who worked under the patronage system: many actually sought court appointments for relief from financial worries.

Theories and genres

Self-interested artists, assisted by scholarly associates, established hierarchies of subject matter. Treatise writers placed history painting, the istoria, the counterpart of literary epic, on top. In both forms, heroic human actions express high ideals—and thus, depicting the male body was essential. Women, however, were excluded from training that involved drawing male nude models. The theoretical project to distinguish artist from artisan, moreover, linked the fine arts to the liberal arts, thereby insisting that true art required an intellect. Writers had long argued that women lacked this capacity and thus could never be real artists. Portraiture was key in the patronage system, but the hierarchy assigned it a subsidiary position to the istoria. Artists admitted their displeasure at having to produce portraits, as they had to please a sitter. Theorized as merely requiring the ability to imitate, portraiture seemed ideally suited to women. Aristocratic portraiture, moreover, has suffered in scholarship from lack of interest, even criticism, for its lack of immediacy and emotion.

If such portraits appear formal, it is not for lack of talent or intellect: the genre presented its own challenges in the representation of dignity. Appearance ruled in the Renaissance and for women, whether in person or as portrayed, outward appearance signaled inner virtue, i.e. honor. The stakes could not have been higher, and sitters sought artists with the ability to produce the appropriate image and accoutrements.

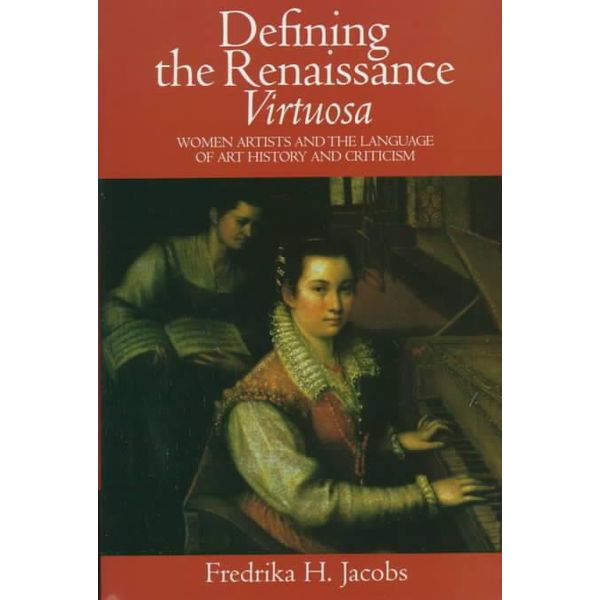

Fredrika Jacobs wrote an important book, Defining the Renaissance Virtuosa: Women Artists and the Language of Art History and Criticism, about the critical language applied to early modern women artists.

From her perusal of a range of texts from antiquity to the Renaissance, Jacobs concluded that writings also applied masculine terms to describe the best artistic styles, as noted by Wiesner-Hanks in her analysis of Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock’s Old Mistresses: Women, Art, and Ideology (Bloomsbury, 1981; republished 2013).

Opinions on quality

There is a reported interchange between Michelangelo and his close confidante Vittoria Colonna that is is well-covered in scholarship. When she praised Flemish painting as being particularly devout, he contrasted the surfeit of details in Northern painting negatively with the boldness and vigor of Italian art. He concluded that the former appealed to “the devout and to women, especially the very old and the very young, and to certain monks and nuns, and even to gentlemen who had no sense of true harmony.” Renaissance Florence was a “math culture” where numbers modeled the world. True harmony, as Michelangelo and his contemporaries understood it, depended upon proportions based on ancient architecture and sculpture, and the male body.

Taste is developed, not innate. We are acculturated by what we read, what we hear, what we see on display. Statements such as Michelangelo’s, echoed by others, have been very influential. Jacobs noted how words like ardito, furioso, virile appear in positive stylistic descriptions, while arrendevole (pliable), tenero, femminile, gentile, are negative designations. Diligenza (attention, diligence, care, painstaking), applied primarily to females, was somewhat ambivalent, but it carried mostly negative meanings. On occasion these descriptors were applied to style irrespective of the gender of the artist. Jacobs notes that Guido Reni’s work was occasionally described as da donna, fiamminga, and senza forza, while his Bolognese contemporary Elisabetta Sirani received virile and grande.

What Michelangelo failed to recognize, and excoriated here, was actually an alternative style very much in demand. Art was a business, and in the Counter-Reformation era, many patrons and collectors sought devotional images that were tenero and gentile, and portraits that displayed details. Both Sofonisba and Lavinia produced artworks that were strong in these qualities.

The purpose of copying

For all artists, training involved copying, but not as an end in itself. The idealized imitation of nature, made possible by the artist’s intellect, was the goal for an artist to be considered great. Typically, women artists are praised for their ability to copy others, full stop. Vasari, the fountainhead for much of this critical vocabulary, found a way to praise the Florentine nun painter Plautilla Nelli by noting that she had been able to copy drawings by her fellow Dominican, Fra Bartolommeo, who practiced the High Renaissance style he most admired. He considered her copy of a Bronzino work, moreover, to be her best.

And Vasari admitted that her work graced the homes of gentiluomini throughout Florence, the social status of a patron or collector being a key indicator for him of an artist’s worth.

Seek and ye shall find

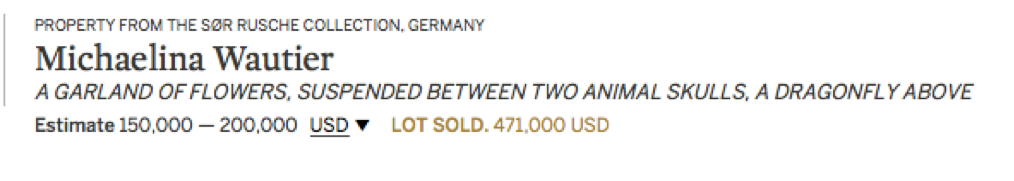

Because she felt that it maintained the assumptions of canonicity intact, Nochlin warned against believing that if we look hard enough, we’ll inevitably find some women artists equal to those great male artists endowed with genius. In the intervening decades, archival research has revealed a greater number of women artists from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and more information about those we already knew of. Still, there remains a frustratingly low correlation between names and artworks that can be attributed. A 2018 exhibition held in Antwerp featured the career of an artist previously unknown to most (Michaelina Wautier: Glorifying a Forgotten Talent, curated by Katlijne Van der Stighelen, Antwerp 2018). Significantly, the Fleming Michaelina Wautier (1604–89) worked in multiple genres, even the prized narrative/istoria. Her oeuvre includes a large-scale Bacchus replete with many nudes.

As often happens in such instances, the owners of works profiled in this exhibition offered them for sale, hoping to capitalize on new recognition. Wautier’s case brought one huge commercial success, wherein the painting sold at over twice its high estimate. But it also brought a failure, in the instance of a portrait. Works in this genre lag in the art market unless the sitter or the artist is famous, or at least known.

Somewhat ironically, considering earlier academic hierarchies that assigned portraits and still lifes a lower rank, the latter category today fetches the highest prices for women artists. Fede Galizia, a contemporary of Sofonisba and Lavinia, worked in multiple genres, but it is her still life compositions that now garner top prices.

It seems as though the high price ($2,415,000) realized at recent sale of one of Galizia’s still lifes inspired the city of Trent, in Northern Italy, to consider her worthy of a one-woman show scheduled to open this summer.

Greatness vs. Fame?

If the market is the key indicator of greatness, then most would agree, based on the prices her paintings command in the sale room, that Artemisia Gentileschi has achieved it. Museums in Hartford and London have recently purchased her works, the latter for a high price. At the same time, the London National Gallery launched a public campaign to raise the final two million pounds to “save Orazio Gentileschi’s Finding of Moses for the Nation.” This headline ironically gives the daughter primacy in identifying who Orazio was, and the daughter is probably the more famous now.

Artemisia, therefore, seems to have achieved “fame”: as Ariosto and Vasari claimed all women artists could do, if they only worked hard enough. Nevertheless, many still question whether she is worthy of the label “great.” Note, furthermore, that the National Gallery paid five times as much money to buy Orazio’s piece as they spent on Artemisia’s self-portrait. Of course, his is an istoria, the most highly valued narrative genre, in excellent condition, and with a royal provenance connected directly to his time spent in London, while hers is an allegorical portrait. Although, as a probable self-portrait it surely generated more interest because of her “fame” than if it had been another subject.

On whose authority?

What about art-historical scholarship? Many scholars of both sexes have produced groundbreaking scholarship on Renaissance and Baroque women artists, but are those artists taken more seriously when male scholars write about them? Do they become greater when “mansplained” (e.g. Ward Bissell, Michael Cole, or Jesse Locker)? Nochlin argued—and it has been a mainstay of the feminist critique of the discipline of art history—that white male subjectivity has been normalized as natural, an unquestioned acceptance that this is the way things are. Linda challenged this mindset in her seminar syllabus from 1969. But the grand narrative of art history that some scholars and institutions fiercely protect still struggles with how to insert women into this pre-existing formula without changing its parameters. In her Art Herstory blog post, Sheila Barker pointed out the problem, and the concomitant objections by earlier scholars, that Artemisia’s acceptance into the traditional canon created for other women artists.

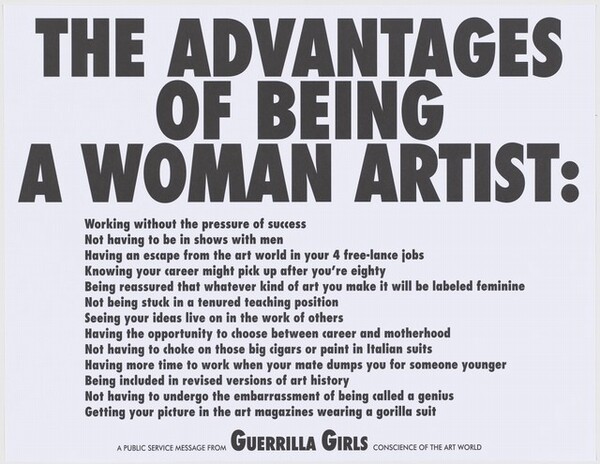

Among their campaigns, the activist Guerrilla Girls produced this poster to point out the obvious regarding attitudes towards women artists in the 1980s:

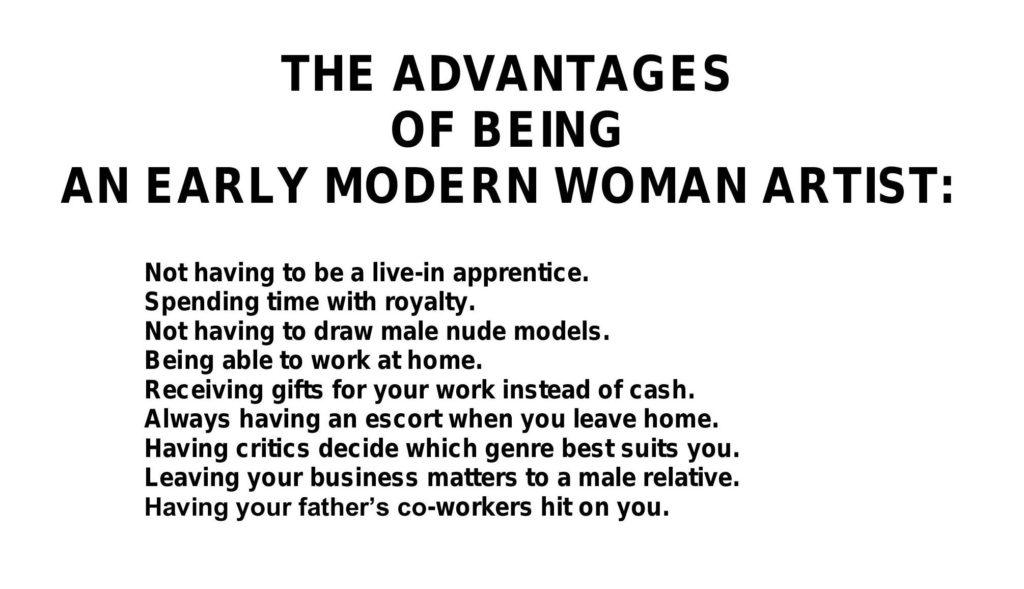

Because we still have a way to go, to provide context for those encountering the works of Renaissance and Baroque women artists for the first time, perhaps an update of the Guerrilla Girls’ manifesto would help?

Dr. Sheila ffolliott is Professor Emerita in the Department of History and Art History at George Mason University. She has spoken and published widely on Renaissance women (Catherine de’ Medici in particular) as patrons and collectors, and on Renaissance and Baroque women artists. Professor ffolliott has helped curate exhibitions at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. She is a Past President of the Society for the Study of Early Modern Women and Gender, the Sixteenth Century Society and Conference, and the American Friends of Attingham. Her recent and forthcoming publications include, among others, “La Miniatrice di Madama: Giovanna Garzoni in Savoia,” in La Grandezza dell’Universo nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni (Florence: Sillabe and Palazzo Pitti, 2020) and “The Agency of Portrayal: The Active Portrait in the Early Modern Period,” with Saskia Beranek, in Agency and Early Modern Women, edited by Merry Wiesner-Hanks (Amsterdam University Press, forthcoming 2021).

If you liked this Art Herstory guest blog post, you might also enjoy:

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Dr. Sheila Barker)

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration (Guest post by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London)

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque