Guest post by Julia Dabbs, Associate Professor of Art History, University of Minnesota, Morris

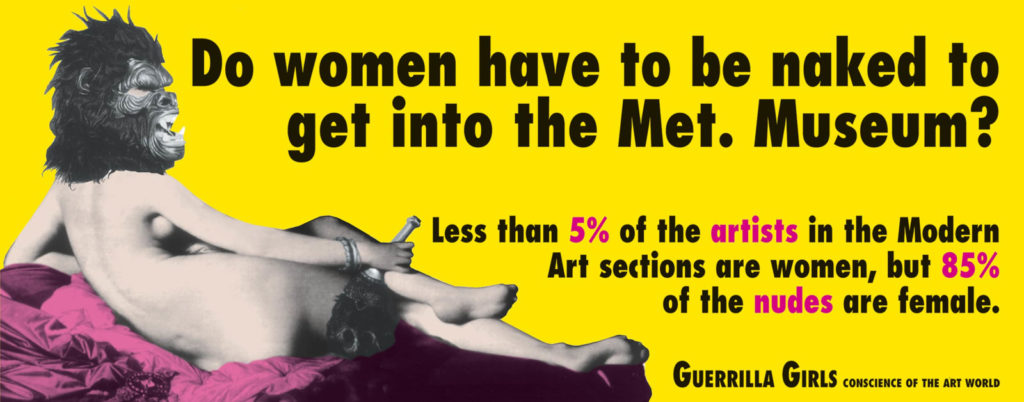

A very laudable goal of Erika Gaffney’s wonderful Art Herstory note cards is to help inform a broader audience about the achievements of historical women artists. But how else might we scholars, teachers, and students help “spread the word” about the contributions of women, whether past or present?

Every two years I teach an upper-level course on “Women & Art,” which covers some of the achievements of women artists from prehistory to the present. The course regularly fully enrolls with art history, studio art, gender studies, and even some biology majors. I first try to impress on students why such a course is needed, and ask them to name some women artists, any women artists. The composite list rarely extends beyond ten names.

We then begin to consider the inclusion of women artists in history as passed down to us via art or art history textbooks or exhibition catalogues. Students randomly choose one of these sources from the past or present; then they count the number of women artists included versus male artists, based on names in the index. After compiling the woefully disproportionate statistics in the next class, students invariably become perplexed and mad. Such inequity, even in twenty-first century publications, was not what they expected! So then, what do we do about it?

Source, Art Institute of Chicago.

In addition to learning about women artists from prehistory to the twentieth century through lectures, discussions, and readings, students in the course take on a research project in which they “teach” the class about a particular woman artist of their choice. However, in recent years I have sought out ways in which they might share that research more broadly, so as to bring the stories and accomplishments of women artists out of the darkness of our art history classrooms and literally into the light. This past year that happened in a number of ways which challenged both me and my students, but thankfully with positive outcomes.

Working with Wikipedia

First, after having attended an “Art+FeminismWikipedia Edit-A-Thon” at our local public library the previous spring, I decided to no longer curse Wikipedia as that resource that “wouldn’t count” on student research bibliographies. I decided to do something about it instead, involving students along the way. With the help of our tech-savvy librarians and a useful pedagogical framework that Wikipedia makes available, we dove into the project last Fall. We had students either substantially add to, or create from scratch, a Wikipedia article on a woman artist of the past or present.

Most of the students chose to research modern or contemporary women artists. Some are relatively well-known and others not so much, but students deemed them all worthy of a Wikipedia article, based on their exhibition record or their contributions to art history. Some examples of artists they selected who, surprisingly, did not have a Wikipedia page yet included New Yorker cartoonist Stephanie Skalisky; Chinese-American artist and curator Baulu Kuan OSB; and Native American beadwork artist extraordinaire Jackie Larson Bread.

Students had little difficulty finding these “gaps” in the coverage of women artists. If they needed assistance, they could turn to Wikipedia’s “Wishlist of Visual Artists” that users have helped compile (although it would be great to see the list include more early modern women artists). We encouraged students new to art history or having difficulty deciding to choose an artist that they could “connect” to in some way, based on such things as personal interests (such as animal portraitists), artistic medium (such as fiber artists), or ethnicity.

But that was the “easy” part. Students then had to find reliable information on their artist, rather than taking the reverse Wikipedia-thon process of using a reference book and then adding that ready-made information to an entry. We talked about what were “reliable” sources of information (and what Wikipedia would accept as “reliable”), and the great responsibility that comes with writing for a reference source that’s so widely consulted. I believe this latter element, so different than the usual context of writing a paper for your instructor, helped raise the students’ commitment to and pursuit of doing excellent work.

For my part, as an historian of early modern women artists who has had her share of digging through rare sources in various languages, I thought that researching modern or contemporary, and predominantly American, women artists, would not be too problematic for undergraduate students—and was I wrong! As one very capable student exclaimed during a research workshop session, “This is the hardest paper I’ve ever had to work on”—and I’m sure she was not alone in that sentiment.

Frustrating, to be sure. But learning resilience and perseverance are key traits for any successful researcher, as well as learning to “dig deep” and be creative in one’s investigative thinking. Students learned to use less-familiar tools such as newspaper indexes, and to cull information from CVs posted to the web. They realized that they needed to be proactive and reach out to museums, galleries, and even living artists for information (students were especially reluctant to do the latter). And were thrilled when they received a helpful reply (oh, if we could only do that with Artemisia Gentileschi!). They also had to learn about the peculiarities of image copyrights to determine whether an illustration of an artwork could be uploaded to Wikimedia Commons (more frustration here, too).

But at the end of the semester, as their articles were made public on the Wikipedia website, they could say that they had helped make this reference source a better place for women artists. And in the process, they learned a good bit about the difficult work of writing history.

Channeling Judy Chicago: A “Women & Art” Tea Party

However, what about making their peers or the broader campus community more aware of the research they had done? For the second time in which I’ve taught the “Women & Art” course, we creatively shared this work in our modest but still meaningful variation of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party installation.

As you may know, The Dinner Party pays tribute, in the form of 39 place-settings and 999 floor tiles, to 1,038 women in history for whom there was typically not a place at the table of historical discourse or recognition. Yet of the 39 prominent women who were the subject of place-settings in Chicago’s installation, only three (Hildegarde of Bingen, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Georgia O’Keeffe) were visual artists (I have yet to go through the other 999 names, but one can find the list here).

For our variation, each student re-purposed and decorated a teacup, obtained from a thrift store, following the stylistic inclinations of the artist they researched. Towards the end of the semester, when we were able to secure some time and space in the university’s art gallery, we set up our three-table installation of the “Women & Art Tea Party” for a one-week period:

Edward J. and Helen Jane Morrison Gallery, Univ. of Minnesota, Morris, December 2018. Author photo.

As can be seen in the photo above, a central “table text” provides an overview of the class project and goals, in addition to describing the artistic source of inspiration. Each place-setting then consisted of the re-designed teacup, and a thrift store napkin of the student’s choice. Most importantly, each student wrote a museum “blurb” providing background on the work and significance of the artist, an explanation of the teacup design, and some key information resources about the artist. A few overachieving students also included a placemat that they had designed or made to coordinate with the teacup. In this second iteration of the tea party installation project, I was again very impressed by the craftsmanship and creativity that went into the teacup designs, especially given that only a few of the students were studio art majors. Knowing that one’s work will be “on display” can be a strong motivator!

Immediately following the installation of the project during a class period, students gathered around the table. Each was asked to briefly comment on the artist they had chosen and how their teacup reflected that artist’s style (see photo below).

This offered a helpful opportunity to ask questions about the medium, technique (how did you do that?) or subject matter. What I hope students also took away was the physicality of being in that important public space, and of being part of something larger than themselves. They too had a place at the table, a vital concept for younger people who may feel that they can’t make a difference. I encouraged the students to post photos of their work, and the project in general, to their social media outlets, which they happily did (see photo below). Some even sent a photo of their teacup creation to their featured artist.

And then, with our invited campus guests, we had some tea, of course (but using disposal cups, not these works of art!). It’s my hope that these public projects on women artists will lead to further recognition of the achievements of individuals who have been marginalized by society. There is still so much more work to be done!

If anyone has questions about the project, feel free to email me at dabbsj@morris.umn.edu.

Dr. Julia Dabbs is an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Minnesota, Morris. She has been researching the lives and accomplishments of historical women artists for nearly two decades, with her major work to date being Life Stories of Women Artists, 1550–1800: An Anthology (Ashgate, 2009). Dabbs has published a number of essays and articles related to historical women artists’ life stories and art, including “Making the Invisible Visible: The Presence of Older Women Artists in Early Modern Artistic Biography” in Ageing Women in Literature and Visual Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) and “Empowering American Women Artists: The Travel Writings of May Alcott Nieriker” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 15 no.3 (Autumn 2016). Her most recent work, an essay on early modern women artists, will appear in the Routledge History of Women in Early Modern Europe (forthcoming Dec. 2019).

More Art Herstory blog posts:

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? (Guest post by Dr. Sheila ffolliott)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Dr. Sheila Barker)

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

Gesina ter Borch: Artist, not Amateur (Guest post by Dr. Nicole E. Cook)

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists (Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton)

An Interview with Carrie Callaghan, Author of “A Light of Her Own”

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew (Guest post by Dr. Laura Gowing)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest Post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): A Birthday Post

An Interview with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Another Dozen Great Women Artists from Long Ago

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest Post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

I’m stealing the Dinner Party idea! It’s brilliant. I teach a similar course, also every two years. Sometimes I start by hauling in a pile of old survey textbooks and asking students to find the women in the index. I’ve also provoked discussion of stereotypes by pairing similar images, one by a woman and one by a man, and asking students to say who made which object. Students like both exercises. My students–no art historians; we don’t offer that major–can choose their own artist from the list I’ve been compiling, but the artist has to be one who was born or died on the student’s birthday. Some of the best papers I’ve seen have come from students choosing a woman on whom almost nothing was available, and you report similar results.

Thanks so much Lisa for your comments, and I’m glad you’re borrowing the teaparty idea! Having the students choose an artist who was born or died on their birthdate is a wonderful idea — you must have quite a list!

Anyone else doing special projects with their students in Women & Art courses? Any challenges you’re facing?

Awesome! We also did a Wikipedia Edit-A-Thon at University of Northern Iowa! And wrote about it! 🙂 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/radicalteacher/article/view/517