Thoughts on the MIA’s Exhibition of Native American Women Artists

Guest post by Elizabeth Sutton, Associate Professor of Art History, University of Northern Iowa

A Nation is not conquered until the hearts of its women are on the ground. Then it is finished, no matter how brave its warriors or how strong its weapons.

—Cheyenne proverb

Source, First American Art Magazine.

This proverb accompanies the piece Hearts of Our Women (2015). Shan Goshorn (Cherokee, 1957–2018) placed historical photos of Native women onto small woven baskets. These faces surround a larger basket whose fibers extend upward like flames, reminiscent of the fires of home and tradition that women sustain. Goshorn added names of more than seven hundred women (historical and contemporary) to the basket interiors to recognize and give voice to the legacy of historical Indigenous women, and women today. Through hundreds of women, archived in and on woven baskets, a new history is written.

Women are the heart of a people, and the “Hearts of Our People” exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art clearly conveys this concept. The works on display show that the hearts of women—made manifest visually and in song, poem, action, and leadership—are, indeed, the hearts of a people. The curators sought to answer the question “why do Native women make art?” through exploring the themes of Legacy, Relationships, and Power. This exhibition answers: women are the pulse that keeps communities, ecosystems, earth—all of us together—alive.

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Women have always been creators

The exhibition is a complex narrative of female Indigenous life and its interwoven threads of trauma, generosity, and survivance.[1]At the entrance to the show, Juanita Espinosa, a local community organizer, artist, and advocate for Native people and art, greets visitors in English and Dakota via video projection. She introduces visitors to the concepts that women have always been creators, and that “art” is a European idea; there is no word for art in Dakota (or in many non-European cultures) because creating is part of life. Mona M. Smith, the Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota Oyate artist who made the video, reminds viewers that to make art is one way “to honor those who do the work that makes our lives possible … thank you.”

Dakota Oyate artist) video greeting, featuring Juanita Espinosa, at the Hearts of Our People exhibition. Photo by author (Elizabeth Sutton).

Invoking tradition through art might be expected, but Espinosa reminds visitors, too, that we are on Dakota land. Meanwhile, a virtual Mississippi River babbles below our feet and the wind rustles conifer trees playing across the adjacent wall. In effect, the walls of the MIA’s European Beaux-Arts building are reclaimed as Indigenous land. Each transition between the galleries’ themes is a time lapse video projection of Indigenous land—from the mixed forests and flowing fresh waters of Northern Minnesota to the eroding mesas of Arizona—the videos show the vastness, variety, and living breath of the landscapes that Indigenous women continue to honor and sustain through their creations.

“Legacy” demonstrates the ever-present engagement with tradition—the ineffable and continuous blending of past and present. Many older pieces—probably by women[2]—are carefully juxtaposed with work by contemporary artists. Most striking to me was the photograph Kaa (2017) by Cara Romero (Chemehuevi, born 1977).

Source, Gerald Peters Projects website.

Kaa Folwell is the granddaughter in a dynasty of potters from Santa Clara Pueblo. Romero collaborated with Folwell to personify the spirit Clay Lady. Folwell’s body is covered in Pueblo designs from an ancient Mesa Verde vessel, similar to the ancient Pueblo olla on display adjacent. Romero explained that this is a piece about empowerment—a necessary piece at a time when one in three Native women are missing or murdered. Here, Folwell’s body is not an object, but full of life, caught in a dynamic moment of transformation, a human body malleable yet durable like the malleability and durability of earth and fired clay.

Irony is a form of survivance…

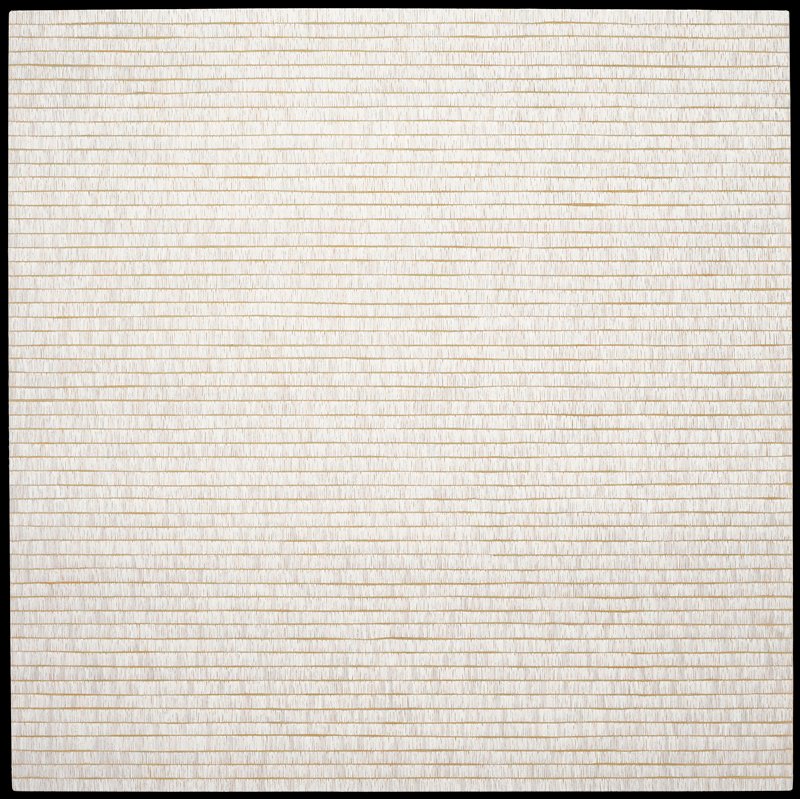

Another work contrasting the power of Native tradition to the norms of settler-colonial institutions, is the painting Untitled (Quiet Strength) by Dyani White Hawk (Siĉháŋğu Lahkóta (Brulé) born 1976). Shimmering lines of white and gold recall quills—and minimalism—and open a space for close looking and contemplation.

As Juanita Espinosa told visitors upon entering, we are on Dakota land. If you are reading this in the Americas or Australia, you are on land taken from Indigenous people. And as in US politics, the art world has been slow to reckon with the legacy of settler colonialism.

Minnesota artist Julie Buffalohead (Ponca, born 1972) references the power and ignorance of white people, especially in the context of the so-called art world, with her work The Garden (2017). The drawing references Sam Durant’s sculpture of a gallows meant for the Walker Art Center’s Sculpture Garden. The work was supposed to be about the largest mass execution in US history: thirty-eight Dakota and two Ho-Chunk men hung by order of Abraham Lincoln in 1862 in New Ulm, Minnesota. The Walker Art Center and the artist received widespread criticism for co-opting Indigenous voice on Indigenous land.

Source, Bockley Gallery.

Here, Buffalohead references not only Durant, but the iconic (and perhaps, facile) “LOVE” sculptures of Robert Indiana, sketched here amidst the trickster coyote, who holds a blue rooster in its maw (the Durant sculpture initially was installed next to a whimsical blue rooster) and a rabbit who offers a kneeling woman a cherry on a spoon (referencing Claes Oldenberg’s Spoonbridge and Cherry). The rabbit distracts her from another rabbit with a noose around its neck. Irony is a form of survivance, and love is power. Buffalohead empowers herself and her people, on her terms.

A step toward healing

While many works convey heartache, not all works in the show evoke the trauma of settler colonialism—many pieces are joyful and full of love and its concomitant power. What white people often want to put into false dichotomies are aspects of the complexity and richness of human life in balance. Humans have the ability to hold the material alongside the ethereal and understand both as animate, living forces; we can hold pain at the same time as joy, we can recognize power and voice, in silence.

Objects, poems, and songs have long been media used by women to heal. They continue to heal, if we spend time with them. This show is an important step in decolonizing spaces that are inherently unequal and have long benefited a few through the dynamics of power that have summarily and systematically eradicated and oppressed brown and female voices. An exhibition such as this is integral to the process of healing these historical traumas. It speaks truth and requires viewers to look, listen, and engage, to understand. The galleries are made small and intimate. Many of the wall labels include the artist’s native language alongside English. The audioguides mostly are comprised of interviews with the artists.

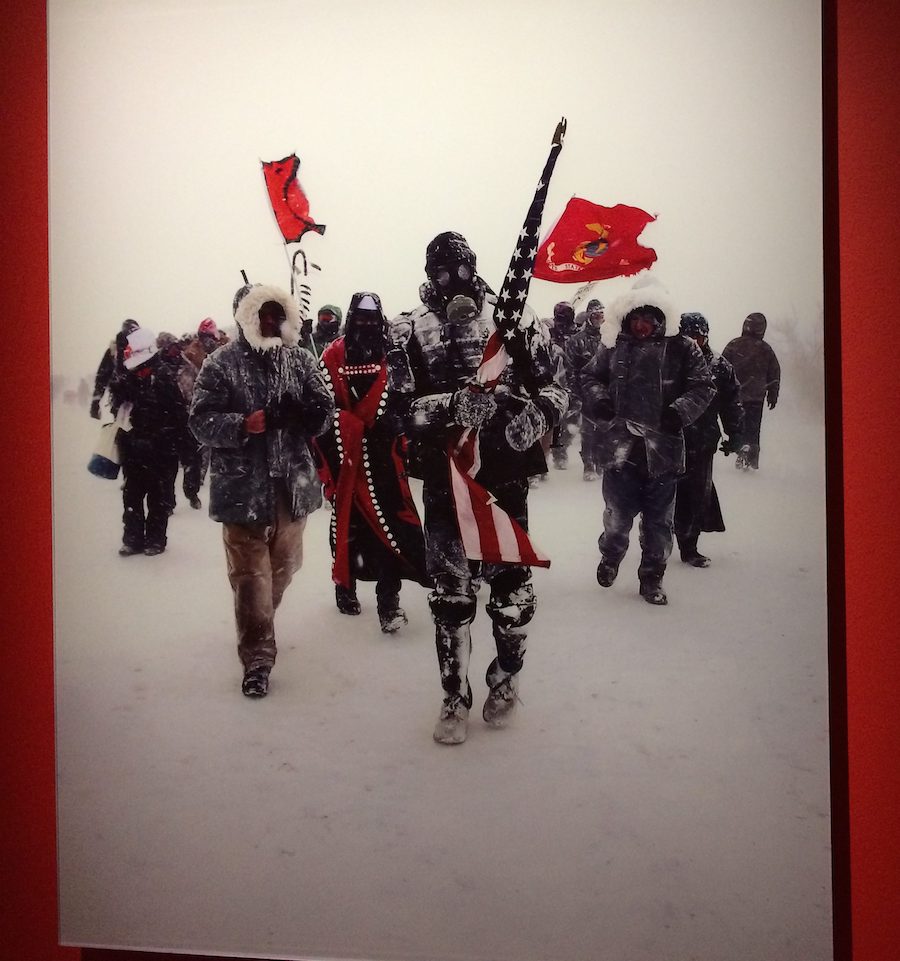

Photo by author (Elizabeth Sutton).

It is appalling, if not surprising, that it has taken until 2019 to have a show that acknowledges Indigenous women as creators of material things, of history, community, and life itself. It is important that this listening and decolonizing process doesn’t stop at the MIA, but that it is woven throughout the landscapes we all now share—both physical and political landscapes (cultural landscapes are, of course, political). The image December 5, 2016: No Spiritual Surrender by Zoe Urness (Tlingit, born 1984) of water protectors at Standing Rock is poignant in its visual power and its continued resonance with contemporary politics. The protectors wear blankets, parkas, and gas masks, and carry tribal, state, and American flags as they march forward in blowing snow.

Now, water protectors in Carlton County, Minnesota continue to combat Enbridge as that corporation and its cronies attempt to build a new oil pipeline through the sacred rice and fishing lakes of the Anishinaabe. Indigenous women, are, as ever, playing leading roles speaking truth, organizing, and thereby empowering communities to sustain and honor creation.

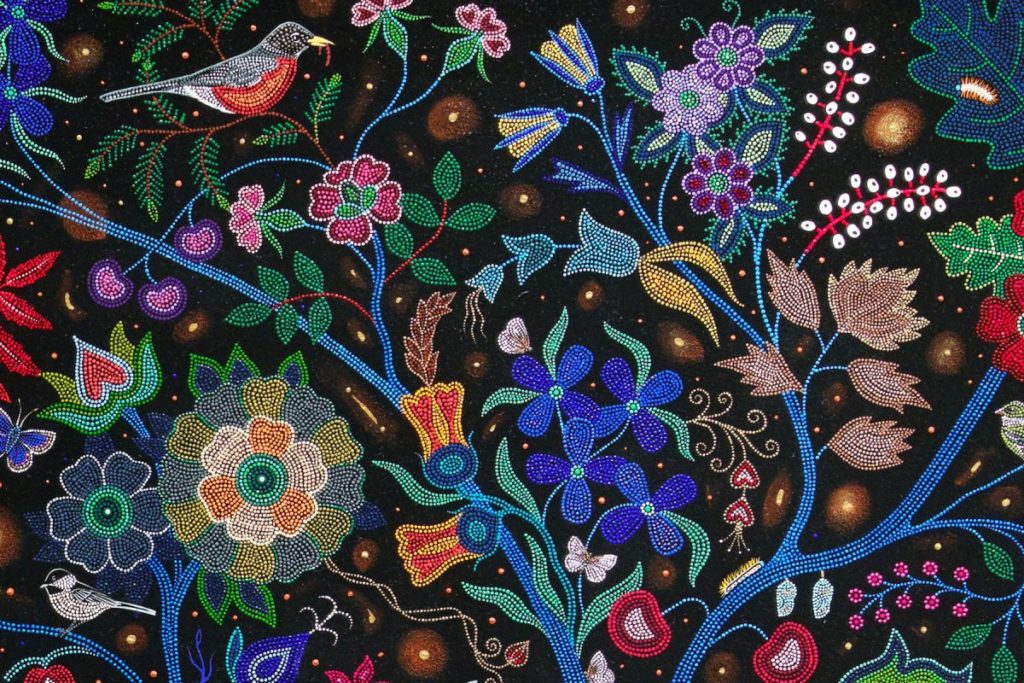

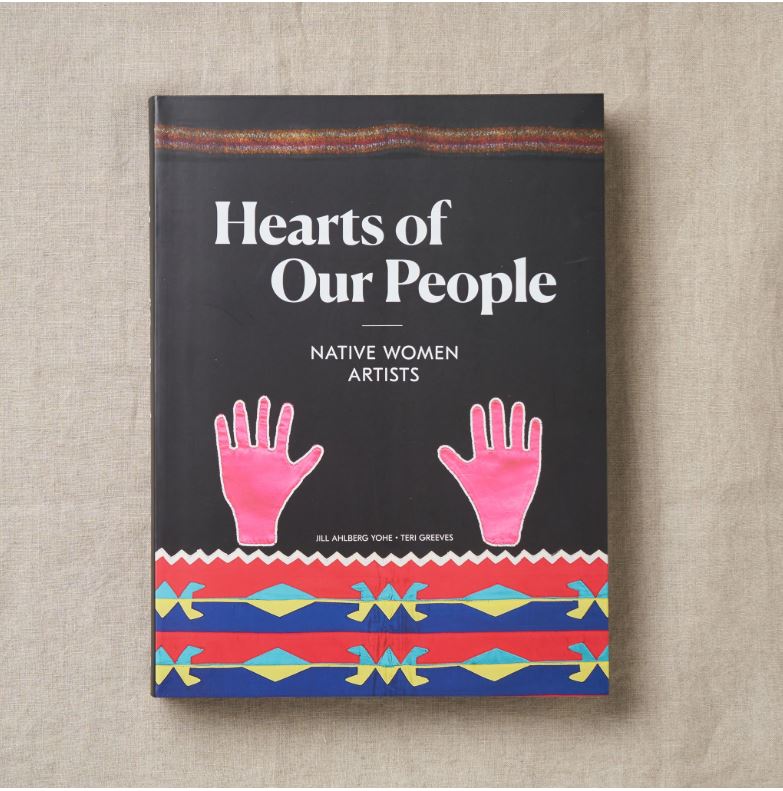

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, presented by the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, opened at the Minneapolis Institute of Art on June 2, and runs through August 18, 2019. Also of interest is Waasamoo-Beshizi (Power-Lines), a group exhibition (closing August 30) at the Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota. The Fargo show features work by 25 contemporary Ojibwe, Dakota, Lakota, Nakota, Eastern Band Cherokee, Seneca, Cree/Flathead, and Ponca women artists.

Dr. Elizabeth Sutton is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Northern Iowa. Her scholarship, while specializing in issues of globalization and power in art and in art history, also has included active pedagogical research. She is author or editor of five books, including Women Artists and Patrons in the Netherlands, 1400-1700, forthcoming Summer 2019. Her current interests include various interdisciplinary projects that seek to amplify feminist research, methodology, and pedagogy.

Following its debut at MIA, “Hearts of Our People” will travel to the Frist Museum in Nashville September 27, 2019–January 12, 2020; to the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. February 21, 2020–May 17, 2020; and to Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa June 28, 2020–September 20, 2020.

[1]Survivance, coined by Gerald Vizenor, is “an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories. . . renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry.” Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), vii.

[2]See Jill Ahlberg Yohe, “Animate Matters: Thoughts on Native American Art Theory, Curation, and Practice,” in Hearts of Our People (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, in association with the University of Washington Press, 2019), 178.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post by Natasha Moura)

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew (Guest post by Dr. Laura Gowing)

More Art Herstory blog posts:

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest Post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): A Birthday Post

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest Post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)