Thoughts on the marquee event of the Museo del Prado’s 200th-anniversary celebration

Guest post by Natasha Moura, Madrid-based art blogger, educator, writer and cultural manager

The exhibition A Tale of Two Women Painters just opened at the Museo del Prado in Madrid. The show reunites some of the most important works of two great female masters of the Italian Renaissance: Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana.

Two female Old Masters of sixteenth-century Italy

Anguissola and Fontana, both Italian women artists who lived in the sixteenth century, were pioneers in the history of painting. They represent two different models of female creators, whose personalities and accomplishments played decisive roles in blazing new trails for later female artists to follow. They broke down stereotypes assigned to women in relation to the practice of art, and overturned scepticism about women’s artistic abilities.

The exhibition sets out to connect with modern sensibilities by recovering, and bringing close to visitors, two artists who achieved recognition in their time, but who were forgotten for a very long time in art history. It brings together an important corpus of paintings of different subjects and genres, such as self-portraits, portraits, and religious and mythological painting.

Self-portraits

The first room of the show is dedicated to self-portraits. Each artist portrayed herself as a virtuous woman of the Renaissance. Each depicts herself at the easel or playing an instrument, in line with the precepts dictated in books such as Baltasar Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier. In the same section, among the self-portraits of Anguissola and Fontana, is the beautiful Self-portrait by Caterina van Hemessen. This work is the first self-portrait of a woman at an easel—it represents the first time a woman portrayed herself as a professional painter. This portrait was probably the inspiration for Anguissola’s Self-portrait at the Easel (shown above).

Sofonisba Anguissola’s evolution as an artist

The next rooms of the exhibition take visitors on a journey through the lives, art, and the worlds of these two artists. Starting with Sofonisba Anguissola’s years as a pupil of Bernadino Campi and Bernardino Gatti, we see how her paintings of her family and herself evolved until she achieved excellence in drawing and painting. Paintings such as The Chess Game, Family Portrait, which is unfinished, or the wonderful self-portrait in miniature, give us insight into her creative process.

Other works of this time that need to be mentioned are Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1559), in which Sofonisba’s likeness is presented as the ‘work’ of Campi. There is not unanimous agreement about whether Anguissola or Campi painted the picture, but in either case, it is a masterpiece. There is also the beautiful drawing Old Woman Studying the Alphabet with a Laughing Girl, one of two Anguissola drawings sent to Michelangelo. Portraits of the nobility, the humanist circle of Cremona and Bologna, are given prominence the show. Within this section, I want to highlight the amazing Portrait of Pietro Manna by Anguissola’s sister Lucia.

The display of paintings executed by Sofonisba Anguissola in the Spanish court of Philip II, when she served as lady-in-waiting to Isabel de Valois, is one of the most important rooms in this show. The problem of incorrect attributions of several works painted by Anguissola while she worked in Spain is well explained. At that time, Anguissola was not permitted to sign her works, since she was not officially a court painter. Also, royal portraits were always painted according to rules established by court painters such as Alonso Sánchez Coello, the most important portraitist of the court of Philip II. In this section there are paintings by other portraitists of the court, as Sánchez Coello and Juan Pantoja de la Cruz.

Religion and mythology in the work of Lavinia Fontana

The room of religious paintings is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful of the show. It was great to see Anguissola’s religious works—most of them were completed unknown to me—as well as Lavinia Fontana’s version of Judith and Holofernes. I loved seeing some of Fontana’s greatest paintings, such as Noli me tangere, one of my favourite pictures of the whole exhibition.

Uffizi Galleries; source, Wikipedia.

I also loved the display dedicated to Fontana’s mythological paintings, which include some of her most daring works. The section deliberately emphasises her role as a pioneer, since she was the first woman to depict mythological subjects. She was also the first woman to depict nudes and erotic scenes. Mars and Venus, 1595, was one of the best surprises of the exhibition.

Fundación Casa de Alba, Madrid, via Apollo Magazine.

Conclusion

The last room of the exhibition was completely unexpected to me. It presents works by other artists, as a way to contextualize Anguissola and Fontana their own time. I can understand the intention behind it. However, I don’t think it is a good way to close the show, since every other section of the show highlights the importance of both artists as pioneers who achieved recognition among their contemporaries. This section was unnecessary, or should be presented as a curiosity. But in my opinion, the show shouldn’t end with it.

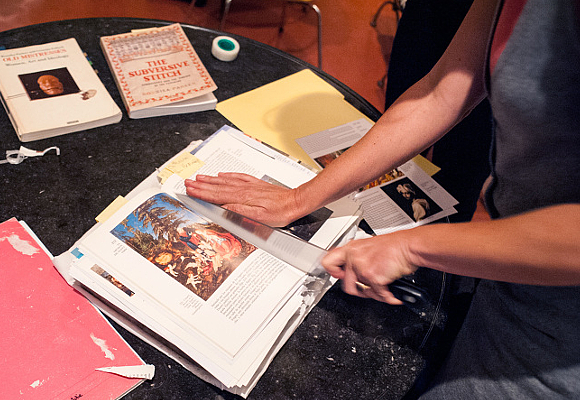

The show’s exit presents a version of Inhabiting Absence, a protest performance by contemporary artist María Gimeno. The project makes space for women artists, positioning them in their rightful place within the history of art. There is a timeline, from the tenth century to 1881, which visually represents the artist’s performance Queridas viejas. In it, she literally slices up Gombrich’s iconic history of art book, in order to augment its entirely male list of artists by adding 78 female artists who were excluded from the official account. This timeline is a metaphor of the low visibility of women artists, and the difficulty of accessing their works.

In my opinion, the exhibition is a great opportunity to introduce the work of both artists, who are not as well-known as some of their contemporaries, to a significant number of people. It is also an amazing opportunity to see some of the best works of Anguissola and Fontana under the same roof. However, I found the exhibition incomplete. To explain further, my impression was that Anguissola’s career is well-detailed and explored, while I found that Fontana’s career and works were treated a bit superficially. I missed some of Fontana’s iconic works, such as the Portrait of the Maselli Family, the Portrait of Antonietta Gonzalez, or the Portrait of the Gozzadini Family, three of the most important portraits by this painter.

This show marks only the second time that the museum has dedicated an exhibition to female creators. (The first such exhibition was The Art of Clara Peeters, in Winter 2016/17.) Despite the shortcomings I found in this current show, I see the Prado to be evolving in a positive direction.

In accordance with Museo del Prado policies, which do not allow photography within exhibitions, this post does not include any photos from the show.

Natasha Moura is a writer, cultural manager and educator based in Madrid. She is the creator of Women’n Art, a blog having to do with the role of women in art history. Follow Natasha on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

**

As of November 2020, Art Herstory offers two note cards that feature the art of Sofonisba Anguissola. Visit the shop for details.

Another Art Herstory blog post about Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana:

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

More exhibition reviews from the Art Herstory blog:

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, Guest post by Dr. Jesse Locker

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi (Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard)

Do We Have Any Great Women Artists Yet? (Guest post by Dr. Sheila ffolliott)

The Politics of Exhibiting Female Old Masters (Guest post by Dr. Sheila Barker)

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596-1676), Convent Artist, by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once-Visible: 18th-century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Dr. Ann Golob

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today?, by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks

Natasha, thank you so much for this fascinating and insightful review of the Prado show. I wish I could see this exhibition in person, but your commentary made it come alive for me. Great work!

Amy, thank you so much for your kind comment! I’m happy that I could make you feel inside the exhibition, though it was only through my words.

Thank you Natasha for this insightful review; I am travelling to Madrid in January especially to see the exhibition and am very excited to see it for myself! While I am looking forward to learning more about Sofonisba Anguissola, my primary interest is in Lavinia Fontana. Having lived in Blois for a time, I met her through the portrait of Antonietta Gonzales. I had not been able to establish whether that portrait was in the exhibition so I am glad to be forewarned that it isn’t (but I travelled to Blois to see her again in the summer so I am not too disappointed!). Thanks for your insights, I’ve followed you on Twitter and look forward to learning more from you.

Ruth, thank you very much for your gentle comment. I am glad that you liked the review so much! Also, it is nice to know that you’re coming to Spain especially to the exhibition. When you’re in Madrid let me know, I would love to meet you.