Guest post by Kathleen G. Arthur, Professor Emerita, James Madison University

Caterina Vigri (1413–1463) is the best-known Italian convent artist among a half-dozen fifteenth-century examples. On her saint’s day, March 9, we remember her accomplishments as a charismatic teacher, devoted nun, and dedicated artist.

Caterina Vigri’s Background

Because she became a saint, Vigri’s manuscripts and personal breviary are preserved as religious relics in Corpus Domini, Bologna. Although she lived most of her life in Ferrara, Vigri is known as Catherine of Bologna, after the convent she founded there. When she died in 1463, she was buried in the nuns’ cemetery. An unusual smell emanating from her grave caused authorities to exhume her body. They found it incorrupt, a sure sign of holiness. She was beatified c.1526, and later canonized. As her reputation as a religious mystic grew in the sixteenth century, serious consideration of her artwork faded.

Caterina grew up at the court of Niccolo III d’Este as lady-in-waiting to Niccolo’s young wife Parisina Malatesta d’Este. Women’s education at the d’Este court was not advanced, as it was in nearby Mantua. Documents suggest she learned to read and write through tutoring by the d’Este court librarian. In 1425, Niccolo discovered Parisina’s affair with his son and executed them both. This proved to be Caterina’s turning point toward religious life.

Caterina Becomes a Nun

She entered a house of pinzochere, which evolved into an Observant Poor Clare convent. As mistress of novices, she was responsible for molding new entrants to the community into pious obedient nuns. She wrote a little treatise, The Seven Spiritual Weapons, which explains how to fight the devil by following Christ’s example of obedience.

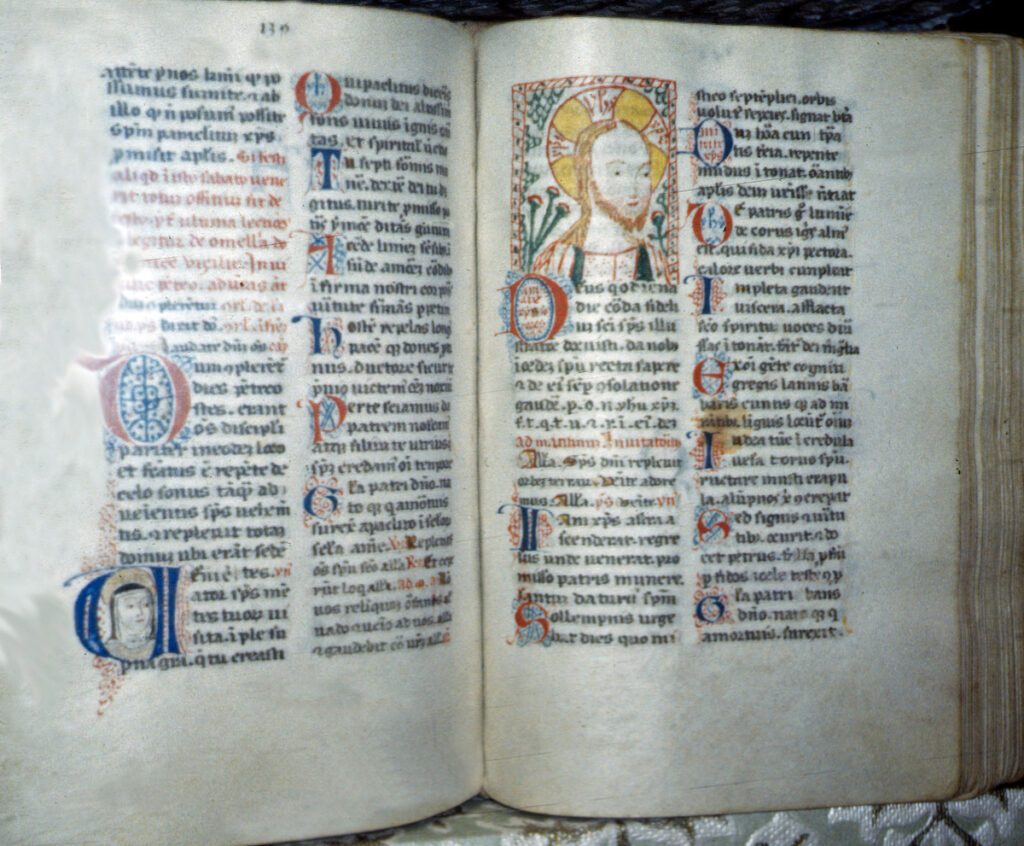

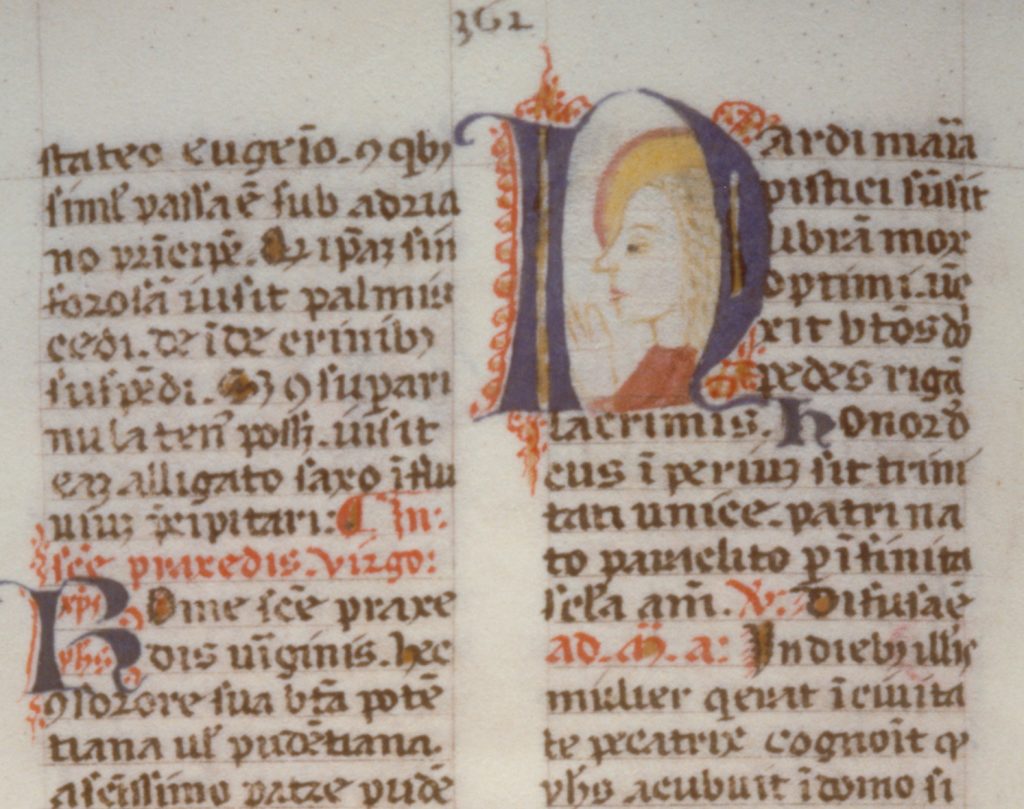

The miniature portrait by Taddeo Crivelli in the Gualenghi d’Este Hours (Image 1) conveys Sister Caterina’s high status as a holy woman. This is virtually unique as a portrait of a contemporary religious woman. It was painted in Ferrara shortly after her death; both the artist and patron, Orsina d’Este, almost certainly knew her. She wears the gray habit of the Franciscan Poor Clares and stands with hands folded in devout prayer. Crivelli depicts light radiating from her head like a beata, but the startling realism of her troubled frowning face show her humanity.

Caterina Vigri as Artist

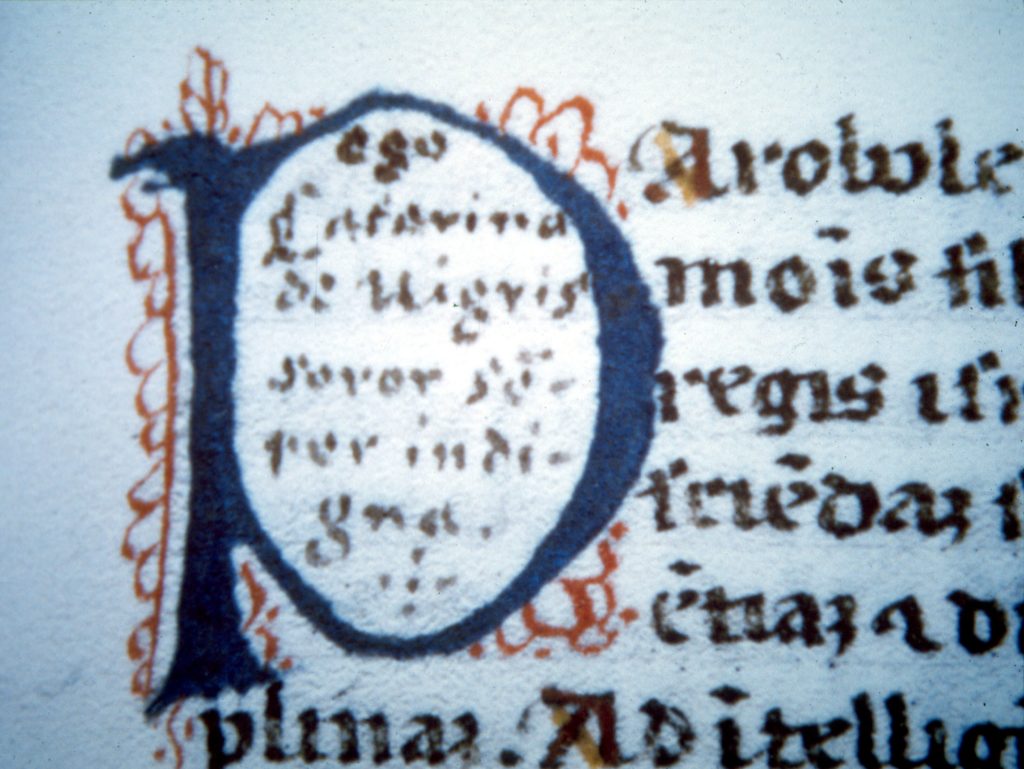

Caterina’s activity as an artist began in the convent of Corpus Christi, Ferrara in the 1430s. According to Sister Illuminata Bembo, her hagiographic biographer who wrote in 1469, she painted images of the Christ Child on the walls of her convent. Her devotion to the infant Christ was expressed in both her writing and drawings. She began to copy and illustrate her own breviary (Image 2) at the same time.

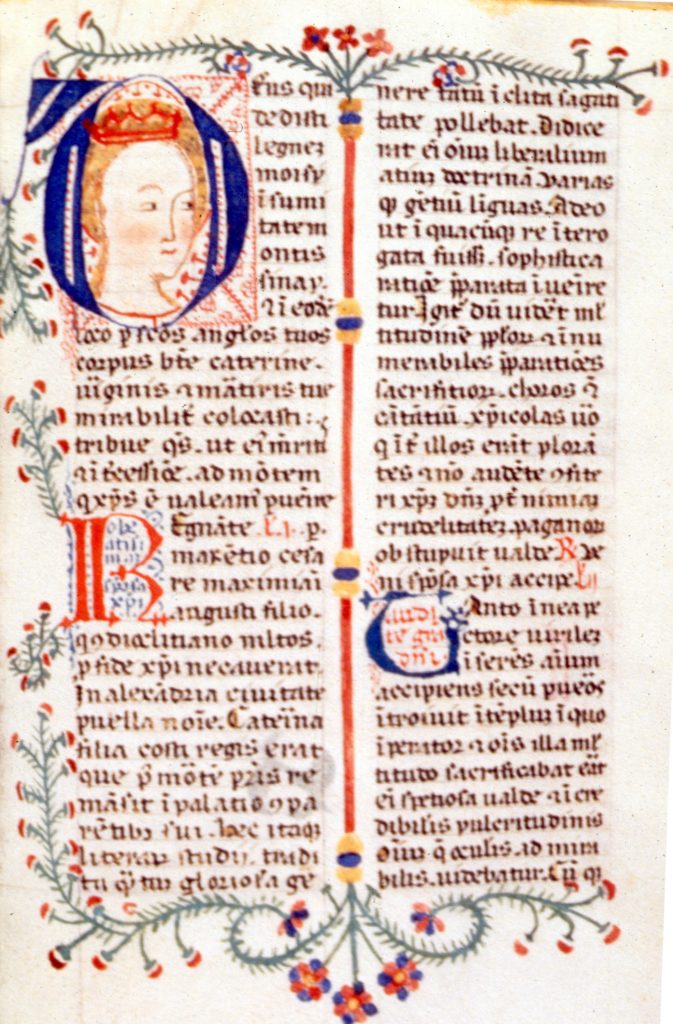

Nuns’ breviaries were small-format liturgical prayer books of about 500 pages, not usually heavily decorated. While it is possible that Caterina saw a few women’s Books of Hours as a child at court, there does not appear to be any specific model for her work. She illuminated her breviary with about fifty simple contour drawings of Christ, the Christ Child, and saints, using red, blue, green, and yellow hues, and signed her name in one of the initials (Image 3). In another text, Vigri herself explained that the purpose of her art was “to increase devotion in herself and others.”

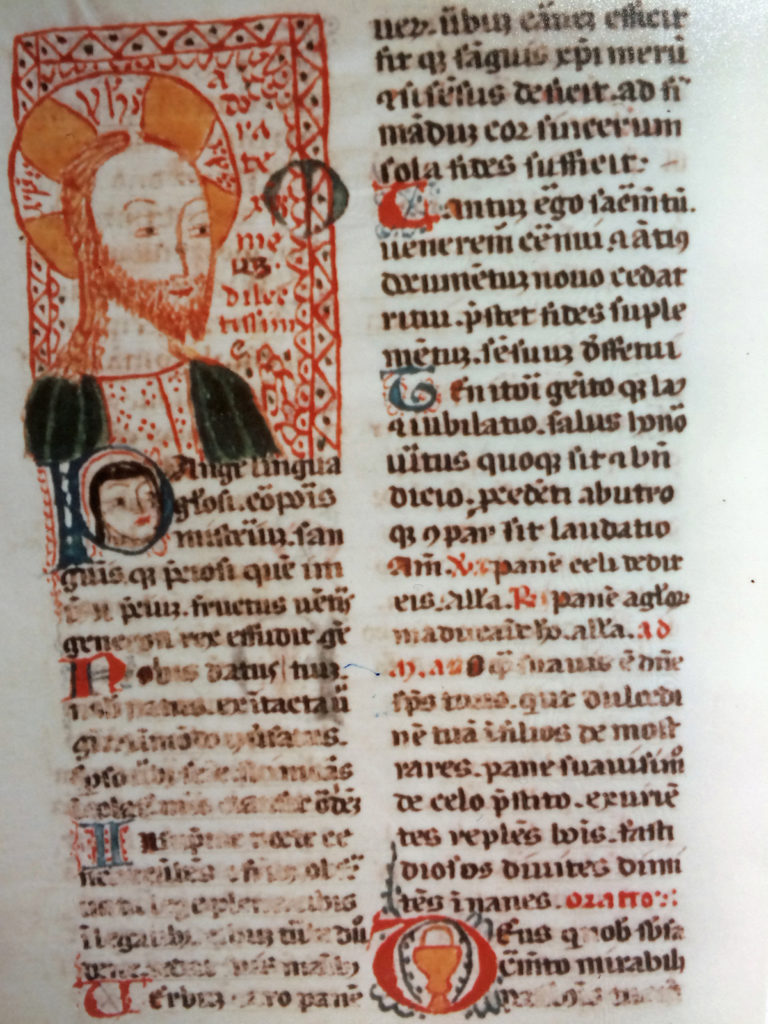

Sister Illuminata Bembo states that Caterina Vigri disdained the animals, birds, and flowers of the North Italian International Gothic style. However, some pages of her breviary display an International Gothic layout and lyrical spirit, like this one with Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Image 4).

Instead of exotic flowers, she used thistles and Marguerite daisies. Instead of monkeys and birds, she incorporates needlework such as scalloped edging, drawn lace, blanket stitches, and handkerchief patterns derived from linen corporals for the Eucharist. Her designs suggest a deliberate humility appropriate for a Poor Clare nun. They also confirm the close relationship between the arts of the needle and the pen.

A second characteristic of her art is the interpolation of personal comments—laudatory titles for saints, poetic prayers to Christ or the Christ child, and exhortative phrases to the nuns. She created a mystical interactive dialogue between herself, the nuns, and Christ. Several times she depicts the faces of nuns adoring Christ (Image 5). Caterina inserted the words “Christus Meus” (My Christ) some 350-375 times! Haloes and capital letters say “Listen,” or “Love Christ, my sisters.” Using words as decorative ciphers is a very modern concept.

Unique Visual Interpretations of the Saints

Caterina was self-taught, but her art should not be considered primitive or naive. She was freer than professional male artists to invent idiosyncratic images outside Renaissance norms. Nor was she trained to follow a master’s formal techniques. Her close reading of the breviary and vernacular texts inspired thoughtful, expressive interpretations of the saints.

The image of Saint Clare, founder of the Poor Clares, is larger than most initials in Caterina’s breviary, and her head and shoulders project outside the frame. (Image 6). The rubric calls her “our mother, humble servant of Christ, and lover of poverty.” Simply drawn, her eyes are downcast, conveying her humility. The ideals of poverty and humility are further expressed in the plaid veil, a textile which, because it was the cheapest kind of cloth at this time, signifies poverty.

Caterina depicts both Mary Magdalen and Francis in profile portraits with their lips parted as if speaking to the reader. The Magdalen is entitled “apostle,” emphasizing her closeness to Christ. Loose blonde hair falls to her shoulders and a lightly drawn hand is raised in salutation (Image 7). The raised hand probably alludes to the Noli Me Tangere, when she recognizes the risen Christ, but cannot touch him because he has not yet ascended to heaven.

Saint Francis appears twice, accompanied by ten rubrics and prayers. For the feast of the Stigmatization on October 4 (Image 8), Caterina alters the traditional iconography, omitting the seraphim and rays of light. She depicts the narrative moment after Francis receives the stigmata, which was described in a popular fourteenth-century text but never previously illustrated. The Fioretti (Little Flowers) of Saint Francis relates how he descended Mount La Verna in a trance, blinded by Divine light. Caterina creates an image of his mystical contemplation of the Divine, symbolized in the gigantic blazing sun.

This reminds us of Francis’ belief in the divine beauty of nature and his poetic words in the Canticle of Brother Sun and Sister Moon, “Praised be You my Lord with all Your creatures/ especially Sir Brother Sun/ Who is the day through whom You give us light./ And he is beautiful and radiant with great splendor/ Of You Most High, he bears the likeness.”

The Artistic Genius of Caterina Vigri

Caterina Vigri’s miniatures fit into our conception of early modern women’s art in several ways. The artist adapted needlework designs and used simple formal means. The initials are single bust-length figures and narrative scenes are lacking. However, Vigri’s art stretches the boundaries of this notion. What scholars and art critics have not realized is the extent to which this convent artist manipulated language and visual images, studied texts, and invented new interpretations. “Ingegno,” meaning genius, creativity and inventiveness, was a highly prized characteristic for fifteenth-century male artists. Perhaps, after six hundred years, we can grant that Caterina Vigri also possessed some of that elusive quality.

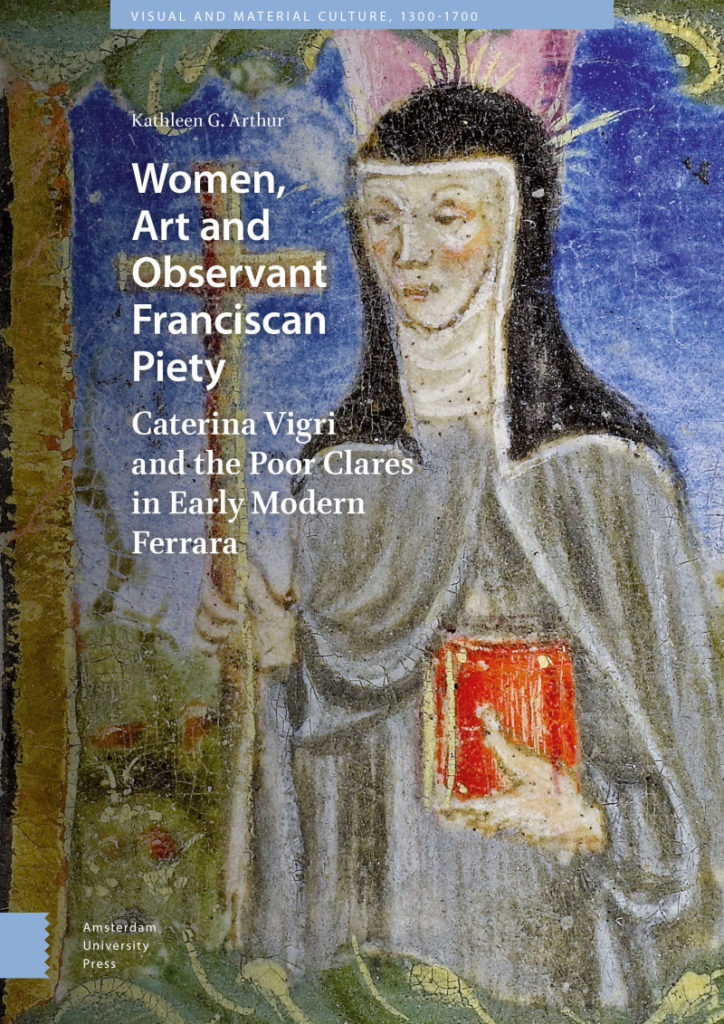

Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur is Professor of Italian Renaissance Art (emerita) at James Madison University. Her book Women, Art and Observant Franciscan Piety: Caterina Vigri and the Poor Clares in Early Modern Ferrara (Amsterdam University Press, 2018) has been reviewed in caa.reviews, Religion and Gender; The Medieval Review, and Renaissance Quarterly. In addition to her work on Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna), she has also published on self-portraitist Sister Maria di Ormanno degli Albizzi. In addition, Kathleen has an article forthcoming on a third fifteenth-century convent artist and scribe, Sister Veronica of Verona.

More Art Herstory blog posts about artist-nuns:

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Portrayals of Mary Magdalene by Early Modern Women Artists, by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Angela Ghirardi

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Plautilla Nelli and the Workshop of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, by Alessia Motti

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Patricia Rocco

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Elisabetta Sirani: Self-Portraits, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Babette Bohn

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Elizabeth Lev

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Consuelo Lollobrigida

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, Guest post by Anastazja Buttitta

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Ann Golob

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian,Guest post by Emma Steinkraus

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Judith W. Mann

Thank you for this wonderful blog post about St. Catherine. She is my daughter’s patron saint chosen because she is also an artist prone do creating similar drawings along the margins of her notes. I can’t wait to show her this post and the images.

Do you know where I can find an image of her St. Ursula painting?

Thank you-

Thank you for the interesting article and excellent magazine!

Earlier it was believed that the painting “Saint Ursula with four Saints and St Catherine da Bologna” was painted by Catherine Vigri.

І. GALLERIE DELL’ACCADEMIA DI VENEZIA:

https://www.gallerieaccademia.it/santorsola-e-quattro-sante-vergini

Autore

Giovanni Bellini (attr.)

Venezia, 1435 circa – 1516

Titolo

Sant’Orsola e quattro sante vergini.

Catalogo 54

Datazione 1450-1455 circa

Supporto

Tavola, cm 64 x 45

Provenienza

Acquisizione 1816 da Legato Girolamo Molin

Sala XXIII

Home Collezioni on line Collezione.

ІІ. Fondazione Giorgio Cini onlus Isola di S. Giorgio Maggiore Venezia:

http://arte.cini.it/Opere/196693

ІІІ. More interesting information about Katerina Vigri is in the book:

Ragg, Laura Marie Roberts. The Women Artists of Bologna. London : Methuen&Co, 1907. 320 p.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924020692624

Thank you, dear authors!

Thank you so much for this wonderful article. St. Catherine is such an underrated saint who I feel should be more appreciated. It was a wonderful accident coming across this article. Thank you!