A Multi-faceted Illuminator within Artistic and Religious Reforms

Guest post by Loretta Vandi, Independent Scholar

The Eventful Foundation

On April 5th, 1502, at 2 a.m., a group of nine sisters, accompanied by three “wise men,” left San Nicolao Novello convent in Lucca “and their dowries” to found in the same town, with Pope Alexander VI’s approval, a new one, San Domenico “to live the strictest observance.” Only two sisters—also biological sisters, Gabriella, forty years old, and Eufrasia, twenty-four years old—though previously assured to be in the selected group, were left in the courtyard of the convent. After recovering from their disappointment, hand in hand, they escaped from San Nicolao and reached the house of their parents, Costanza Trenta and Giovanni Burlamacchi, one of the town’s wealthiest merchants (Image 1). Since a noble cause justified Gabriella’s and Eufrasia’s escape, at 4 a.m. the two sisters, accompanied by their father and three brothers, joined the group. From that moment onward, they lived according to Savonarola’s monastic reform, first in a house and later in the newly built convent of San Domenico (Image 2).

This eventful occurrence changed Eufrasia’s life. Around 1505, with the help of Sister Benedetta Arnolfini, a consummate miniaturist from San Domenico convent in Pisa, she undertook the first of her artistic enterprises. She wrote, notated, and illuminated five anthem books, MSS 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, now in the Archbishop Alemany Library at San Rafael, in the Dominican University of California. In an autograph note in MS 5, Sister Eufrasia, then thirty-seven years old, declares that she completed the book in 1515 (Image 3). In addition, instead of a feeling of elation for her accomplishment, she refers to the Last Judgment, expressing the wish to deserve a place among the elects to honor the Lord eternally by singing a specific chant. She was also the convent’s cantrix so that her desire to sing that beautiful and solemn chant she quoted from St. John (Revelation, 7.12) was justified: Blessing, and glory, and wisdom, and thanksgiving, and honor, and power, and might, be unto our God for ever and ever. Amen.

Eufrasia had to wait for more than three decades before her wish was fulfilled. In fact, after the five anthem books, by 1523 Eufrasia completed a small Ritual, MS 1984 (Lucca, Biblioteca Statale), around 1527 Antiphonary MS 14 (Lucca, Archivio Storico Diocesano) and eventually, around 1532, the large size two-volume Gradual for the Dominican monastery of San Romano in Lucca, now MSS 2649 and 2650 (Lucca, Biblioteca Statale). Two images from this Gradual brought Eufrasia international recognition as one of the seventeen Italian Women Artists from Renaissance to Baroque, when they were included in the 2007 exhibition in the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., curated by Vera Fortunati.

Devotional Subject or Devotional Style?

Sister Eufrasia’s art belongs to a rich and lively chapter of sixteenth-century Italian illumination. In a convent as San Domenico, grounded on renewed devotion, illumination played an important role in qualifying piety through images of God, Christ, the Virgin Mary, and several saints. But what then was devotional painting? In the second half of the fifteenth century, devotional painting was an expression of content, strictly concerned with the needs of the everyday religious practice and with the direct relation a visual representation bore to a text. But at the beginning of the sixteenth century, it became manifestation of style—that is a cultural fact. In the San Domenico convent, Sister Eufrasia contributed to renew devotional painting, insisting on content expressed in a retrospective, as well as original, style.

The best representative of the “devotional” trend is the so-called “School of San Marco” and its derivations. It was at this Florentine monastery that in the first decade of the sixteenth century the rediscovery of the “sacred” value of Fra Giovanni Angelico’s painting occurred, featuring simplification of forms, limited chromatic gamut, and intelligibility of the religious message. Within the “School of San Marco,” one can distinguish two groups of artists. The first, closer to the rarefied formal and chromatic atmosphere of Fra Angelico, comprises Fra Bartolommeo (Image 4), Lorenzo di Credi, Giovanni Antonio Sogliani, Fra Paolino da Pistoia, Antonio del Ceraiolo, Mariotto Albertinelli, and Cosimo Rosselli. The second, represented by Bachiacca and Franciabigio, presents more popular and neo-primitive accents.

Sister Eufrasia deserves a place in the first group, not so much for her proximity to Fra Bartolommeo, but for her original re-elaboration of subjects depicted by Fra Paolino da Pistoia (Image 5) and Antonio del Ceraiolo.

Saintly Gentleness and Simplicity

Sister Eufrasia focused on “portraits” of saints and sacred episodes, often reproduced twice with subtle stylistic modifications as Nativity, first in c.1515, MS 5, fol. 7v (Image 6), and then in c.1532, MS 2649, fol. 49v (Image 7), or Pentecost, in MS 5, fol. 67v (Image 8) and in MS 2650, fol. 99r (Image 9).

As a rule, she conjugates simplicity and virtuous atmosphere, delicacy, and sentimental purity, as in St. Lawrence, MS 5, fol. 155r (Image 10), rendered with a variety of bright colors. This image reminds us of Antonio del Ceraiolo, who represented the same subject in the predella with nine saints, once in the convent of Santa Caterina in Florence and now in the Accademia Etrusca at Cortona (Image 11).

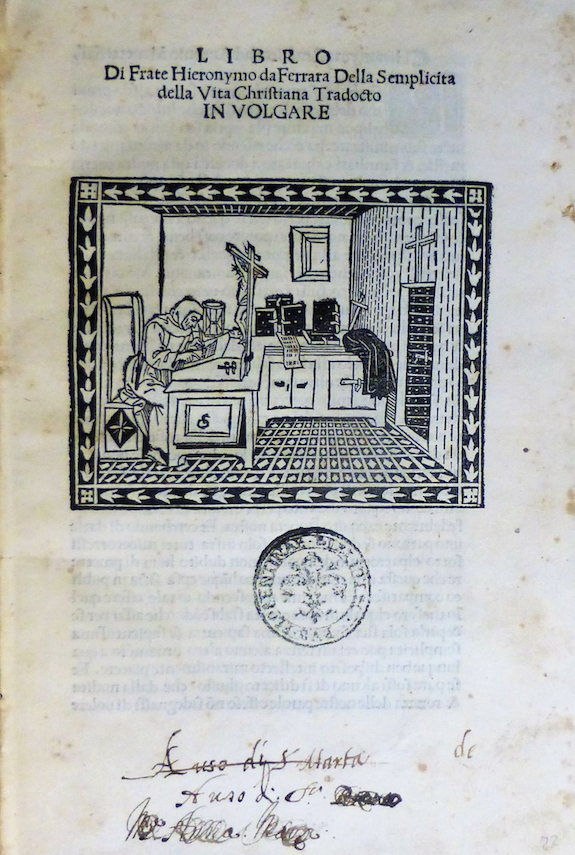

Girolamo Savonarola expressed a clear interest in simplicity in his treatise On the Simplicity of Christian Life, published in Florence in 1496 and read by the sisters of San Domenico in Lucca (Image 12).

He states that root and foundation of Christian life is God’s grace manifested by the true Christian through simplicity in both mind and soul. However, he claims that nature alone is truly and utterly simple, while man’s productions, art included, though imitating nature’s simplicity, are destined to be artificial. Expanding Savonarola’s thought, one may conclude that only ornament was free from any comparison with nature, so that its artificiality never elicited strictures. Many features in Eufrasia’s illumination make clear that she reflected on this resource, successfully combining simplicity of countenance and gestures in the figural images with artificiality of decorative combinations in the initial letters.

From Simple Nature to Grotesque Architecture

Florentine illuminators of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries often depicted complex scenes within complex cityscapes. Eufrasia, apart from her interpretation of Nativity (Image 7, above) and David kneeling before God the Father in MS 2649, fol. 1r (Lucca, Biblioteca Statale) as scenes unfolding in a natural setting (Image 13), always preferred initial letters containing figures with no naturalistic or architectural background.

This compositional choice allowed her to highlight figures and ornament, with a special preference for all’antica patterns. In the five afore-mentioned anthem books, one witnesses her piecemeal exploration of the grotesques.

In MS 1, the first of the series, only acanthus leaves are employed, holding cherries or strawberries (fol. 193v) (Image 14).

In MSS 2, 3, 4, and 5, acanthus ornament is enriched by cornucopias, fruit, dragons, and snakes forming a series of chalice-like shapes (MS 2, fol. 293r; MS 3, ff. 1r, 8r, 147v, 206v; MS 4, ff. 1r, 132r; MS 5, fol. 142v) (Image 15). Chalices, cornucopias, and fruit, along with dragons and snakes organized in symmetrical patterns are the most typical elements of grotesques. However, though typical, they do not exhaust their entire repertory, made of frightening and capricious forms. Sister Eufrasia’s grotesques make us suspect that she feared in some way to draw freely on the multifarious patterns, so that she made only sparing use of masks and zoomorphic and phytomorphic hybrids.

It is in MS 5 that Eufrasia’s most original contribution to Renaissance ornament can be seen, balancing selection and control. As to the former, she employed just a few figural motifs as masks and dragons; as to the latter, she endowed architectural elements, depicted as if they were grotesques, with the potential ambiguity of hybrids. In such a way, the most frightening and capricious grotesque motifs interact unharmfully with the sacred subjects within the letters, as in the initial S framing Pentecost (fol. 67v) and N with St. Peter (fol. 139r) (Image 16).

Geometrical Microcosms

With what competitors did Eufrasia engage? Neither with painters, nor with sculptors or illuminators but with language and music, the sacred language expressed by sacred music. To this aim, she also created pen-drawn initials, carefully outlined, a real tour de force, making visible the tension between the visual and the aural. Even though this choice had been already made in the middle of the fifteenth century by some Dominican illuminators in San Marco in Florence (Image 17), their pen-drawn letters, rendered by extremely thin and elegant lines, neither oppose the heavy notation nor are integral parts of the page.

Eufrasia’s pen-drawn initials (Image 18) are, on the contrary, solid entities that challenge both script and notation, pointing at the visual appreciation of the ornament seen in parallel with the auditory appreciation of the chant. Moreover, the pen-drawn initials, which, with their complexity, challenge the pure orality of the chant, were, in the end, a visual tribute to the chant itself. In such a way, the chant could become visible and lead to a more personal and sustained involvement in the vocal performance, a move in which only a cantrix, also expert in forms and colors, would have succeeded.

Loretta Vandi, Ph.D. Université de Lausanne, has been Professor of Art History at the Scuola del Libro in Urbino. She authored La trasformazione del motivo dell’acanto dall’antichità al XV secolo. Ricerche di teoria e storia dell’ornamento (Bern, 2002), Il Manoscritto Oliveriano 1. Storia di un codice boemo del XV secolo (Pesaro, 2004), Four Essays (Umeå, 2007), Paolo Grossi. L’arte della copia (Fermignano, 2011), and the forthcoming Images on Trial. Three Tuscan Abbesses, Countess Matilda of Canossa, and the Hidden Side of the Gregorian Reform. She edited the essay collection Ornament and European Modernism. From Art Practice to Art History (New York, 2018), reviewed in Leonardo, The Burlington Magazine, The Journal of Art Historiography, and Journal of Design History. She has published articles and reviews in international magazines. She has also contributed to essay collections on medieval illumination, prints and illumination, architecture and spolia, ancient and medieval ornament, popular art and devotion in early modern Europe, psychology of perception and art, women as artists, writers, and art historians. She is currently working on two books, the first on Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi and the second on the reception of preaching within female religious houses of the early modern period.

More Art Herstory blog posts about artist-nuns:

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Plautilla Nelli and the Workshop of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, by Alessia Motti

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Maddalena Corvina’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Kali Schliewenz

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Dr. Patricia Rocco

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Dr. Jitske Jasperse

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Dr. Emma Steinkraus

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

I have been to Lucca and have the Nuns there. I dont remember if they were part of this order