Guest post by Sheila McTighe, The Courtauld Institute of Art

Threatened by pandemic closure but rescued to great acclaim, this exhibition of Artemisia Gentileschi’s work promises to be a turning point in the appreciation of early modern women artists. How will it deliver on its promise?

In one sense, the answer is easy. This is the National Gallery’s first major exhibition devoted to a woman in its nearly 200-year history. You have to start somewhere. The show also welcomes into the National Gallery’s permanent collection a very beautiful early painting of the artist herself in the guise of a martyred saint, one of the recent discoveries that change our view of her career. The Self-Portrait as St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1613–14; Fig. 1) is only the twenty-first painting by a woman in the National Gallery’s collection, in contrast to 2800 paintings by men.

Simply by displaying thirty of Artemisia Gentileschi’s works, albeit temporarily, you could claim some progress toward understanding the significance of women’s careers in the early modern arts.

Life and Art

The curator of the exhibition, Letizia Treves, states the show’s aim more precisely. She hopes it will clarify the oeuvre of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1656) by displaying the best-documented, most securely attributed paintings. The general theme governing the choice of exhibits and the catalogue is the relation of Artemisia’s life to her art. Recent scholarship has uncovered much of the artist’s peripatetic career at the greatest European courts: Rome, Florence, Naples, Venice, London.

However, accounts of her life always begin with the same event. Rome’s Archivio di Stato has lent its document transcribing the 1612 trial of Artemisia’s rapist, the artist Agostino Tassi. In the exhibition, it is open to the page that records Artemisia’s torture under oath, and her cry in response to questioning: “È vero, è vero, è vero” (“It’s true, it’s true, it’s true”).

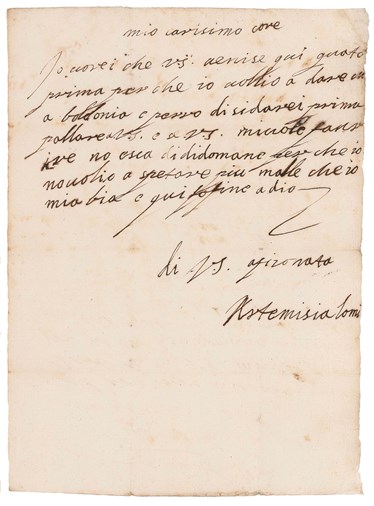

As if that weren’t dramatic enough, six of her passionate love letters to a Florentine nobleman are also on view. These documents may thrill the show’s visitors. They seem to give us unmediated access to her experience.

The catalogue’s essay on these letters by Francesco Solinas, who discovered and published them in 2011, is compelling on the subject of how they shed light on Artemisia’s circumstances in Rome. The letters on display not only reveal her strong, spiky signature (Fig. 2), they are scrawled in her own hand, with phonetic spelling and shaky grammar.

But what do the letters tell us about her art? Mary Garrard, in a 2017 essay, cautioned against the tendency to read them through gendered assumptions about emotionality. Their very accessibility can lead us astray when it comes to understanding Artemisia’s artistry. Paintings such as the two versions of Judith Beheading Holofernes, displayed side by side here, may perhaps express Artemisia’s passionate response to Tassi’s sexual assault (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). They are also cunningly crafted, balancing between lush painted surfaces, elegant compositions and the brutal violence that they depict.

Painting dal naturale or “from life,” and Artemisia as a model

The other achievement of the exhibition, in addition to clarifying the core of Artemisia’s oeuvre, is to show us much more about her working process. Larry Keith’s essay in the catalogue is typically readable and illuminating on the technical study of her canvases. This essay clarifies Artemisia’s relationship to Caravaggio’s art, as well as her departure from the technique of her father Orazio Gentileschi. What brings her closer to Caravaggio is her continued reliance on the live, posed model, the type of painting known as working dal vivo or dal naturale, from life. In particular, she repeatedly used one model: herself.

One wall of the show displays four canvases that are all based on Artemisia’s depiction of her own features. Three of them also bear an underlying relation to one another. Artemisia traced the contours of the figure from one, to transfer the composition to a second and third canvas. Which was the originating work remains unclear, but it is possible to superimpose their outlines on one another. The National Gallery’s own Self-Portrait as St. Catherine (see Fig. 1 above) is perhaps closest to the c. 1612–1615 Self-Portrait as Lute Player (Fig. 5).

Caravaggio duplicated some of his works by tracing their compositions. His friend Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia’s father, also frequently replicated his works in this way. Elsewhere I’ve written about how Seicento artists who worked dal naturale or “from life” adopted—almost paradoxically—this practice of mechanically replicating their art. The work made “from life” had the property of generating new works, emulating the way that nature reproduces itself.

The technique of working dal naturale is an important bridge between the careers of various women artists of the period, particularly linking Artemisia to her contemporary Giovanna Garzoni. (Garzoni’s oeuvre was also the subject of an exhibition this Spring in Florence, organized by Sheila Barker, which I would have given much to be able to see.) The two women seem to have known one another and worked in close proximity in Venice, Florence and London. [See Mary Garrard’s Art Herstory guest post Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi; and Sara Matthews-Grieco’s review of the Uffizi’s Garzoni exhibition.]

Despite Garzoni’s primary focus on still life painting, and the techniques of a miniature painter working in gouache on parchment rather than oil on canvas, the two women shared the traits of close observation and replication of models from one work to another.

There is a larger story to tell about women and painting dal naturale that will wait for another time. When women practiced painting dal naturale or dal vivo, it was portrayed in writing on the arts as femminil pazienza and as that least-appreciated artistic trait, diligenza, a dutiful but uninspired copying of appearances. When men practiced it, the critics portrayed it as the critic Giovan Pietro Bellori described Caravaggio, “making art, miraculously, without art.”

Repetition and Invention: Artemisia’s Depiction of Inward Experience

Artemisia’s depictions of herself extend far beyond this one wall of canvases, however. Versions of her broad face, golden hair, and distinctive nose reappear throughout her oeuvre, in the guise not only of saints but classical nymphs and queens. The show’s curator suggests this is a pragmatic choice governed by the high cost of hiring models. Catalogue entries acknowledge that there is frequently an element of playful role-playing as well. The Self-Portrait as Lute Player (Fig. 5, above), for example, in which Artemisia seems to wear gypsy costume, may derive from a gypsy dance performance at court in Florence. The exhibition brought out another element of Artemisia’s self-portrayal, however. She uses her own body to experiment with that most Baroque of artistic tropes, the inward experience of extreme pain and pleasure, reflected in the outward appearance of faces and bodies.

Her tiny image of Danae of c. 1612 (Fig. 7) is one of several works she composed around a reclining female nude. It is derived from the famous classical sculpture known to seventeenth-century viewers as Sleeping Ariadne, but also recalls the great Venetian precedents like Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Here in this jewel-like painting on copper, Artemisia takes a slightly angled viewpoint on Danae’s body, which heightens our proximity to her. It is the expression of inward rapture on the face and in the recumbent body that is so striking here. She may not have much of the appearance of Artemisia herself—the face is simplified, not portrait-like.

But her much larger painting of Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy of c. 1620–1625 (Fig. 8), though the figure is clothed, explores similar territory with features that recall her own appearance. A large composition, it places the body of the converted prostitute close to the viewer and extending beyond the bounds of the painting. A reversal of the lost painting of this subject by Caravaggio, Artemisia’s Magdalene puts the viewer in physical proximity to the saint but at subjective distance. Her head flung back—golden hair, distinctive nose—is the key to an experience we are invited to contemplate, charged with denoting the extreme of feeling that lies beyond the painted surface.

In recalling her own body, Artemisia may be responding to the Horatian dictum to poets, taken up by early modern artists: “If you would move me, you must first move yourself.” Her repetitions of figures and her use of herself as model show us an essential contradiction in her art, made visible by this fascinating show. In repetition, she achieved that originality that she boasted of when writing to a patron about her powers of imagination: “never has anyone found in my pictures any repetition of invention, not even a single hand.” And in repeating her own singular looks throughout her oeuvre, she may have sought the universality of human emotion that was so central an aim of Seicento arts.

“Artemisia” opened at London’s National Gallery on October 3. It runs until January 24, 2021.

Dr. Sheila McTighe is Senior Lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. She has written about Nicolas Poussin, Annibale Carracci, caricature, and genre painting and prints, focusing on seventeenth-century Italy and France. Her most recent book is Representing from Life in Seventeenth-century Italy (Amsterdam University Press, 2020). Follow Sheila on Twitter at @SheilaMcTighe.

Interested in learning more about Artemisia? Visit the Art Herstory Artemisia Gentileschi resource page!

More Art Herstory posts about Artemisia Gentileschi:

Exhibiting Artemisia Gentileschi; From the Connoisseur’s Collection to the Global Museum Blockbuster, by Christopher R. Marshall

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

More Art Herstory reviews of museum exhibitions featuring women artists:

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Nelleke de Vries

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Dr. Jitske Jasperse

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver