Guest post by Nelleke de Vries, Rijksmuseum Twenthe

From 11 February until 11 June 2023, Rijksmuseum Twenthe hosts the exhibition Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance, on the noblewoman and artist Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532–1625). This is the first monographic exhibition on the Italian woman artist North of the Alps, organized together with the Danish Nivaagaard Collection, and features more than half of her currently known oeuvre. This post presents images of paintings included in the show, as well as an overview of the artist’s life and accomplishments.

Sofonisba Anguissola is one of the most successful artists of the Italian Renaissance, praised by her contemporaries for her talent and creativity. During the initial years after her death, the admiration for Anguissola remained undiminished. For example, in 1674 the historian Raffaele Soprani described her as “la più illustre Pittrice d’Europa”: the most glorious woman painter in Europe.

For the exhibition in Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Anguissola’s personal history forms the guiding principle. Her life is marked by three important moments: her childhood and education in Cremona, her time as a lady-in-waiting at the Spanish court in Madrid, and her later years in Sicily, Genoa, and then Sicily again. Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance traces her artistic development, starting with the early family portraits and ending with the more restrained religious images that Anguissola created during her last years of life.

The Family Portraits

“[…] but most excellent in painting […] has been Sofonisba Anguisciuola of Cremona, with her three sisters, which most gifted maidens are the daughters of Signor Amilcare Anguisciuola and Signora Bianca Punzona, both of whom belong to the most noble families in Cremona. Speaking, then, of Signora Sofonisba […] I must relate that I saw this year in the house of her father at Cremona, in a picture executed with great diligence by her hand, portraits of her three sisters in the act of playing chess, and with them an old woman of the household, all done with such care and such spirit, that they have all the appearance of life, and are wanting in nothing save speech.”

This quote, by the famous Italian artist, architect, and biographer Giorgio Vasari, appears in the second edition (1568) of his Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architetti. He refers to The Chess Game, a uniquely composed portrait of three of Anguissola’s sisters, namely Lucia, Minerva and Europa, and a servant or chaperone. They are playing chess on a table with a tablecloth, surrounded by trees and with a typical Italian landscape in the background. This is probably the first group portrait in history that shows only women.

In addition to this painting, Vasari is also impressed by Anguissola’s unusual Family Portrait, showing her father Amilcare Anguissola, her brother Asdrubale, and again her sister Minerva in the background. Vasari writes that the figures were painted with such skill that they seemed to breathe and to be absolutely alive.

The subjects of Vasari’s influential biographies are almost exclusively men, and as such the kind of praise he gives Anguissola’s family portraits was reserved almost exclusively for the great male artists of the past. But he makes an exception for Anguissola because she had “worked with more grace and diligence […] than any other woman of our time.”

Sofonisba Anguissola grew up in a big family, consisting of her father Amilcare, mother Bianca Ponzoni, sisters Elena, Lucia, Minerva, Europa, and Anna Maria, and brother Asdrubale. Sofonisba and Elena were sent to study the art of painting with the Cremonese artist Bernardino Campi. They lived with him and his wife between 1546 and 1549. They were kept separate from the male pupils working in Campi’s studio, because female pupils were subject to many restrictions at the time.

For example, contrary to her male colleagues, Sofonisba was not allowed to study the male nude or attend anatomy lessons, nor was she allowed to travel on her own, not even to study the landscape surrounding Cremona. Sofonisba turned this limitation into her strength. She focused on the genre of portraiture, and it is no surprise that Sofonisba’s early portraits often show family members—models she could easily study and paint at home.

After her studies with Campi and subsequently Bernardino Gatti, Sofonisba herself became an educator, teaching her sisters the art of drawing and painting. Works by Europa and Lucia have survived. Recent research by Michael Cole in connection with this exhibition resulted in a new attribution to Europa. It concerns another painting from the Nivaagaard Collection. There used to be an inscription on the back of the painting, though it’s now no longer legible. It read: “BLANCA. ORPHEA P. IO. / SCHING VX ~ / DI. BENBO. ~.”

The first two lines seem to indicate that the subject’s first name was Bianca, or Blanca in Latin. SCHING refers to the last name of the woman, which is probably an abbreviated version of the last name Schinchinelli. Europa Anguissola married Carlo Schinchinelli in 1569. His father was named Pietro (or Piero) Giovanni, which corresponds exactly with the P.IO in the inscription. Pietro Giovanni married a woman named Bianca, and although we don’t know her last name, the painting must depict the woman who became Europa Anguissola’s mother-in-law. Considering these clues together with stylistic similarities, Cole was able to add another work to the oeuvre of Europa.

The Self-Portraits

Sofonisba grew up during a period in which new ideas about women and their role in society arose. Various books on modern rules of conduct and desirable characteristics were published during the sixteenth century. One of the most well-known examples is Baldassare Castiglione’s Il libro del cortegiano, first published in Venice in 1528. This book lists all the requirements applying to courtiers and the nobility: the education they should receive, the skills they should possess, the clothes they should wear, the attitudes they should display, and desirable and undesirable forms of behaviour.

In the third chapter, Castiglione focuses on the standards that women must meet. He writes: “No court, however large, can be beautiful, stately, or merry without the presence of women.” Additionally, he writes that they should have a knowledge of literature, music, painting and dancing, among other things.

Sofonisba’s education clearly met these requirements, and her self-portraits show her awareness of them. As a young woman, she learned a series of important humanistic and artistic values and incorporated these into her everyday activities. Several of the self-portraits include attributes emphasizing her talents, such as an easel and a spinet or clavichord. Each portrait shows a different virtue, often combined with the inscription of “virgo,” emphasizing her honorable nature. The connection becomes apparent when you look at this series of portraits side by side. The Self-Portrait at the Easel is also one of the earliest portraits showing a woman painting. With her portraits, Sofonisba plays with the expectations imposed by her gender, and uses these ideals—or this straitjacket, depending on how you see it—to present herself as a confident and masterful painter.

At the Spanish Court

When Sofonisba arrived in Spain in 1559 to serve as a lady-in-waiting to Elisabeth of Valois, the Queen of Spain, Elisabeth was fourteen years old. Sofonisba was approximately twenty-seven. Elisabeth was interested in art, and took an instant liking to Sofonisba, enjoying her drawing lessons. At this time, Sofonisba already had some teaching experience, having taught her younger sisters in Cremona. We know from historical sources that the relationship between the Queen and Sofonisba was close. Moreover, Sofonisba was praised at the court for her beauty, talent, manners, and dancing skills.

Life at the court constituted many social obligations, masked balls, hunts, and performances. Despite her busy life, Sofonisba continued to paint portraits in Madrid. At the time, portraiture was the most important genre in Spanish art. She adopted the official courtly style and like the official court painters, she left her portraits unsigned. As a result, she moved away from the distinctive and innovative style of her early years in Cremona during this period.

After Elisabeth’s death in 1568, Sofonisba became a governess to Elisabeth’s daughters Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catalina Micaela, and remained in Madrid for another five years. Isabella would later become sovereign of the Southern Netherlands from 1621 until her death in 1633. Catalina Micaela would become the duchess of Savoy. The two little princesses became very attached to Sofonisba, and both would meet her again later in life.

Sofonisba’s portraits of the two princesses were painted shortly before she left Spain. The younger one, Catalina Micaela, had just turned six; in her portrait she holds her beloved pet marmoset, which also serves as a reference to the Spanish colonies. Sofonisba’s portraits of both little girls are tender and loving, while according them the adult dignity required by their position.

Back in Italy

In 1573, when Sofonisba expressed her wish to return to Italy, King Philip II arranged for Sofonisba to marry a Sicilian nobleman, Fabrizio de Moncada, Count of Caltanissetta and Paternò. She returned to Italy after fourteen years in Spain. Sadly, the marriage was short-lived: after less than five years, Fabrizio drowned during a pirate attack off Capri. During her subsequent trip back to her parents’ home in Cremona, at the age of 47, Sofonisba fell in love with the captain of the ship she traveled on: Orazio Lomellino of Genoa.

In remarrying, Sofonisba casts aside the conventions that would normally apply to a widow of the Spanish court. She asked permission neither from her brother Asdrubale, who was her legal guardian after Moncada and her father had died, nor from Philip II. After a short stay in Pisa, Sofonisba and Orazio first moved to Genoa in 1581. Throughout her life, Sofonisba continuously painted religious subjects. Some of these paintings date from her early years, but it was in Genoa that she most of them, taking inspiration from a famous local artist, Luca Cambiaso.

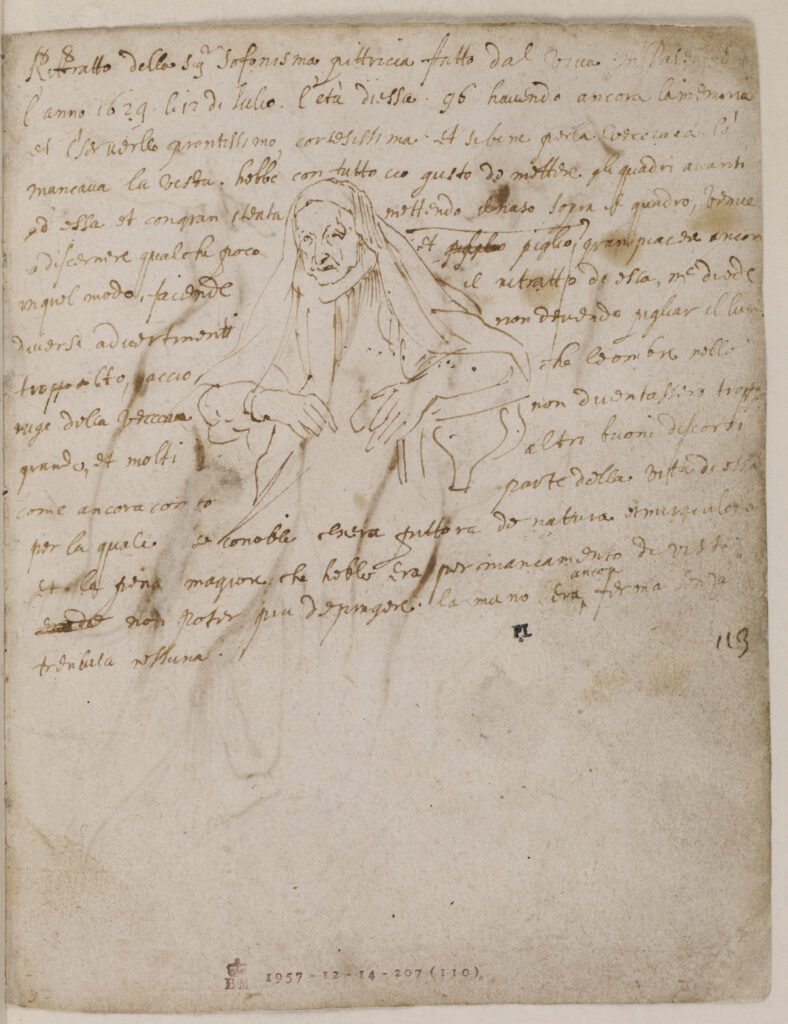

In 1615, the couple moved to Palermo. She died there at the age of 93, after forty-five years of marriage. The year before her death, in 1624, she received a visit from the famous Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck. In his diary entries, he describes Sofonisba as being clear of mind, and mentions how she was an extraordinary painter of human nature. Later on, he would recall how he had learned more from her than from any other colleague.

In 1632, some seven years after her death, Orazio Lomellino ordered a memorial plaque for the church of St. Giorgio dei Genovesi in Palermo, bearing the following inscription: “To Sofonisba, my wife, whose parents are the noble Anguissola, for beauty and extraordinary gifts of nature, who is recorded among the illustrious women of the world, outstanding in portraying the images of man, so excellent that there was no equal in her age. Orazio Lomellino, in sorrow for the loss of his great love, in 1632, dedicated this little tribute to such a great woman.”

Nelleke de Vries is Curator of Old Masters and Modern Art at Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede, the Netherlands. Previously, she has worked at Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar, the RKD-Netherlands Institute for Art History and the Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen in Berlin. Between 2018 and 2021, she was a doctoral researcher at the Institut für Kunstgeschichte of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich and member of the ERC-funded project SACRIMA: The Normativity of Sacred Images in Early Modern Europe. Her dissertation examined the migration and adaptation of iconographical and visual motifs between Northern and Southern Europe between 1470 and 1530. Her research focuses on the artistic connections between different geographic regions and the impact of emerging art markets and trans-European networks of patronage on the artistic production of the period, as well as the role of materiality and the phenomenon of the early modern copy.

Be sure to visit Art Herstory’s Sofonisba Anguissola resource page!

More Art Herstory exhibition-related posts:

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

More Art Herstory posts about Italian women artists:

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Danielle Carrabino

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Elizabeth Lev

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Adelina Modesti

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Alexandra Letvin

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Katherine McIver

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Kathleen G. Arthur

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Judith W. Mann

Thank you for this post! May the exhibition receive the praise and many visitors it deserves.