Guest post by Jitske Jasperse, the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Artemisia Gentileschi in the Netherlands

Artemisia: Woman & Power (Artemisia. Vrouw & Macht) is the title of the exhibition at Rijksmuseum Twenthe. The show presents 15 paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–after 1654) together with artworks made by her contemporaries. Several rooms take us through Gentileschi’s life and work, starting with her self-portrait (fig. 1). Then follows motherhood, with a painting of the Virgin breastfeeding her son. The wall text explains that Artemisia had five children, of which only a daughter (Artemisia Prudenzia) survived. Although not stated explicitly, the text suggests that her motherhood shaped her intimate depiction of Virgin and Child (fig. 2). This prompts the question, why are such observations rarely made when men’s work is exhibited?

Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence.

Did men not engage with, or were they not affected by, family life? After motherhood, the visitor continues with viewing other representations of women, including Susanna and Cleopatra. In a smaller room one sees Artemisia’s Bathsheba, which connects the portrayal of women and men with the final room, which focuses on powerful women.

According to the accompanying brochure, Gentileschi deservingly is one of the most important artists of the Italian Baroque: not despite her being a woman, but because she was one. Indeed, her skill in representing lifelike figures and in capturing the moments just before the dramatic event takes place, such as the snake biting Cleopatra’s breast, is undeniable. In other instances, our attention is focused on the events shortly after the climax, such as Judith and Abra with Holofernes’ head.

Perhaps Gentileschi portrayed her Cleopatra, Judith, Susanna, Bathsheba, Jael, and Mary Magdalene in such captivating ways, because as a woman she could identify with them. In these paintings she shows her ability to portray woman as active, independent, and fearless, even in precarious situations (fig. 3).

The exhibition also addresses the challenges Gentileschi faced because she was a woman. The story of her rape by Agostino Tassi, a colleague of her father’s, is well known: the trial was a public affair and after it Artemisia went to Florence. Throughout her life she had to prove herself artistically and intellectually to men. And her patrons tried to negotiate the prices of her artworks or delayed their payments; clearly Artemisia had to fight harder for her earnings than her male contemporaries. If this sounds familiar, it is largely because the same mechanisms are still at play.

Women and Art

Feminist art historians have long debated—and are still discussing—how women artists should be represented in art history. One way is to create “women exhibitions.” This started with Women Artists: 1550–1950 in 1976, which was curated by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin (fig. 4).

Here, the curators highlighted women’s contributions to art history. Also, they discussed the societal mechanisms that limited women in their development as artists. For example, women weren’t allowed to study and draw nude models, which was crucial for creating history paintings. And rarely did they have access to academic institutions responsible for artists’ training, their promotion at exhibitions, and the creation of networks. Importantly, Harris and Nochlin questioned art history as a male dominated discipline. The Artemisia Gentileschi exhibitions—including the Dutch one—are part of this “women exhibition” tradition.

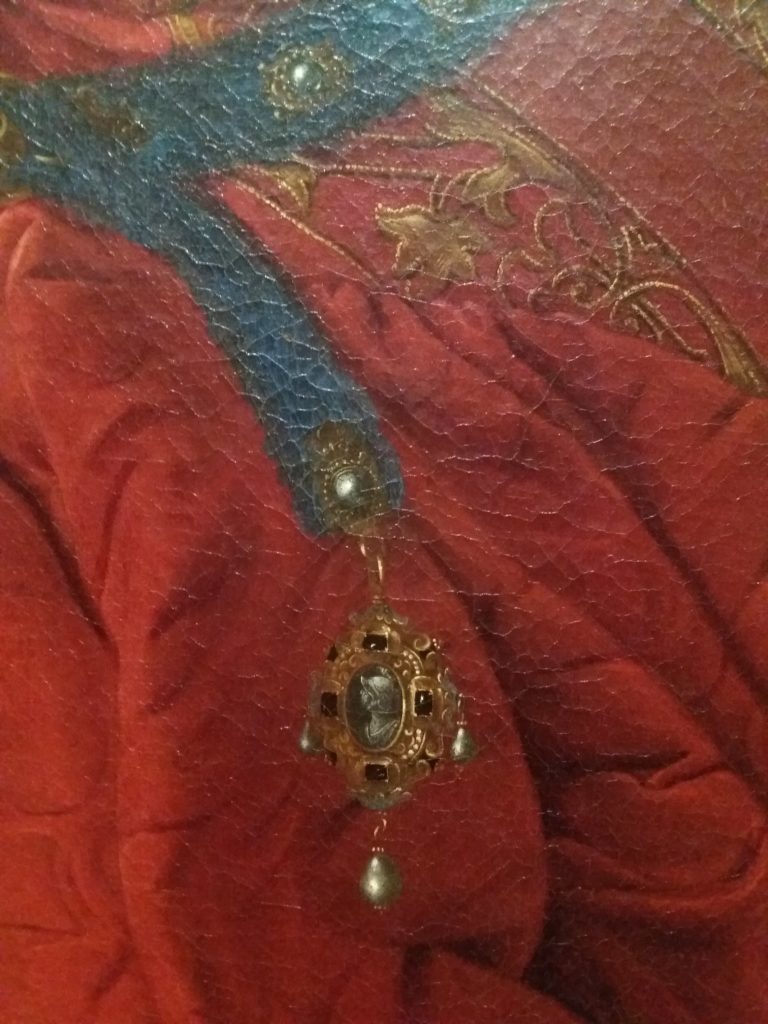

My recent Dutch book The Female Eye: Women as Patrons, Collectors and Artists addresses some of the issues raised by feminist scholarship (fig. 5). While Artemisia Gentileschi does not appear in the book, her contemporary, the Flemish painter Clara Peeters, does. Even though they worked in different genres and styles and accommodated a different clientele, both displayed an artistic self-awareness in their works. This can be seen, for example, in the signatures they added to their paintings. In Clara Peeters’ painting at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, she left her mark behind on the richly carved silver handle of the knife: CLARA PEETERS (fig. 6).

Two signed works in the exhibition, among them her Minerva, reveal Artemisia Gentileschi’s full name, inscribed in this form: ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI FACIEBAT, that is, “was being made by Artemisia Gentileschi” (fig. 7). This signature is not without meaning. First, it indicates that Gentileschi herself deemed her last name just as important as her first name. This made me wonder why the exhibition, like its predecessor exhibition at London, is titled Artemisia. Clearly, both museums want to underscore that her forename had—and has—an enormous resonance (just like Michelangelo’s or Rembrandt’s). Second, the past imperfect tense (“faciebat”) suggests that the painter knew the work of Pliny, who considered “faciebat” as an expression of ongoing artistic creation.

Women’s Agency, not just as Artists

Like the Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition, my book argues that a more inclusive narrative emerges when we acknowledge that women have always shaped the production, collection, and reception of art, and often did so with enormous self-awareness. I show that women were not just artists, but also patrons and collectors. Like a medieval triptych, the scenes on the side panels—patrons and collectors—make the most sense when studied together with the middle panel—artists and artefacts. Without artists there is no art to commission, display, gift, collect, and treasure. The already multi-layered narrative of women and art becomes even more dynamic when we unfold the triptych to include women as patrons and collectors.

This also allows us to see that medieval women’s engagement with artefacts was not necessarily different from (early) modern women’s. To give just one example, I view Subh’s ivory container from tenth-century Cordoba, Margaret of Austria’s bird of paradise from the “New World,” and Joséphine de Beauharnais’s collection of exotic flowers, in terms of their foreign origin and how this impacted their social value. While each object, together with its owner, has its unique story to tell, as a group they show that travel and exploration (and exploitation) shaped women’s lives and determined the social life of artefacts.

Women on the Move

Artemisia Gentileschi was well acquainted with the physical and social movement of women. Trained in her father’s workshop in Rome, she did not stay there, but moved to Florence, Venice, and Naples. There, she died, possibly in 1654.

How these travels and new environments exactly impacted her life is beyond the scope of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe exhibition. The show does, however, make clear that the artist’s movement allowed her to engage with a range of artists, artworks, and patrons. This network of people and art works inspired her to paint women in impressive and intimate ways. Many of the subjects she depicted, moved by personal and political circumstances, took matters into their own hands. With her vibrant use of colors and eye for detail (fig. 8), which helped her to shape her powerful figures, so did their creator, Artemisia.

Artemisia: Woman & Power (Artemisia. Vrouw & Macht) is on at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, the Netherlands, through February 23, 2022. [Update: according to ArtsTalkMagazine.nl, the show has been extended, and is now on through March 27, 2022.]

Dr. Jitske Jasperse is an art historian specialized in medieval art and women. Her recent publications include Medieval Women, Material Culture, and Power: Matilda Plantagenet and Her Sisters (2020) and Het vrouwelijk oog wil ook wat: vrouwen als opdrachtgevers, verzamelaars en kunstenaars (2021). Together with Dr. Karen Dempsey she edited “Getting the Senses of Small Things / Sinn und Sinnlichkeit kleiner Dinge,” a special issue of Das Mittelalter (2020). She is the series editor for CARMEN Visual and Material Cultures. Follow Jitske on LinkedIn and Academia.edu.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Sofonisba Anguissola: Portraitist of the Renaissance at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Nelleke de Vries

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A Tale of Two Women Painters, by Natasha Moura

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Dr. Laura Gowing

More posts about Italian women artists:

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Dr. Angela Oberer

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Trackbacks/Pingbacks