Guest post by Ien G.M. van der Pol, Fem Art Collection

To mark the bicentenary of the birth of Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux and Musée d’Orsay in Paris collaborated to organize an exhibition in her honor. Bordeaux was too far away but on December 6, 2022 at 7 am I took the fast train “Thalys” from Amsterdam to Paris where I arrived at 10.30 am. An hour later I was at the Musée d’Orsay. Finally I entered the place I had wanted to visit in order to see the great exhibition “Rosa Bonheur.” I was not disappointed.

The first awesome painting that stopped me in my tracks was Two Rabbits, painted in 1840, when the artist was 18 years old.

Two hundred years ago, Marie-Rosalie Bonheur was born in Bordeaux on 16 March (1822). She was a daughter of the painter Raymond Bonheur and Sophie Marquis, and the eldest of four children. The Bonheur family moved to Paris in 1829. Marie-Rosalie entered her father’s studio at the age of 13. She was a studious pupil. In 1833 her mother died, which was a hard blow for her. In memory of her mother she then started to use the pet name that her mother called her: Rosa.

Her father encouraged her to “blaze her own trail” and to challenge the past masters whose work she copied at the Louvre—and that’s what she did.

Rosa Bonheur’s first submission to the Salon in 1841 was Two Rabbits. It attracted attention; and the artist gradually began to distance herself from her father and his influence.

Right from the beginning of her drawing and painting career, she was dedicated to depicting animals, as well as the relationship between animals and people.

First successes

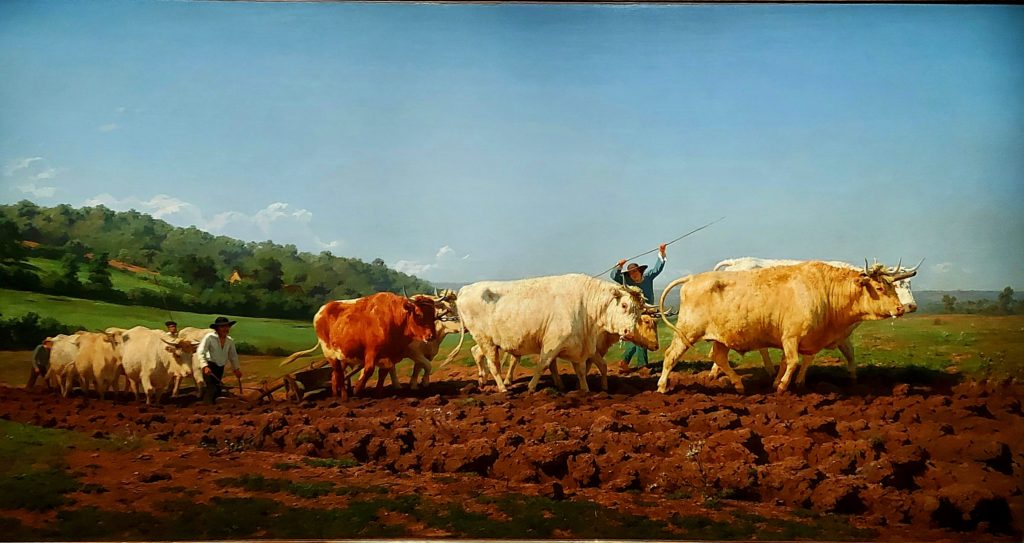

As I walked on in the exhibition hall, there was no missing her famous masterpiece Ploughing in the Nivernais, painted in 1847–1849, which may have been inspired by the opening scene of George Sand’s 1846 novel The Devil’s Pool. With this painting she won first prize at the Salon of 1849.

This is such a well-known painting, but once you stand in front of it, you experience what the viewers at the Salon of 1849 must have experienced: how can anyone paint like this?! How did she convey such dedication to working the land by both the oxen and people? Seeing this picture with my own eyes was something different, which also counts for everything else that followed.

Having established her reputation, she was keen to earn her credentials as an outstanding creative artist by working in a genre traditionally reserved for men and by conferring the large format of history painting on the theme of animals. She succeeded with The Horse Fair, submitted to the Salon in 1853.

The original painting of 1853, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, measures 244 x 506 cm and is too fragile to travel. But the exhibition organizers show on the wall a composition with a full-size sketch on canvas (over two metres high by five metres long), as well as a smaller version from 1852–1855 which she made together with her friend Nathalie Micas (now held by the National Gallery in London). I marvelled at how she managed to convey the power of Percheron draft horses and the violence of men in a realistic manner. Before she started this huge work, Rosa Bonheur made numerous drafts and sketches, many of which could also be seen in these rooms.

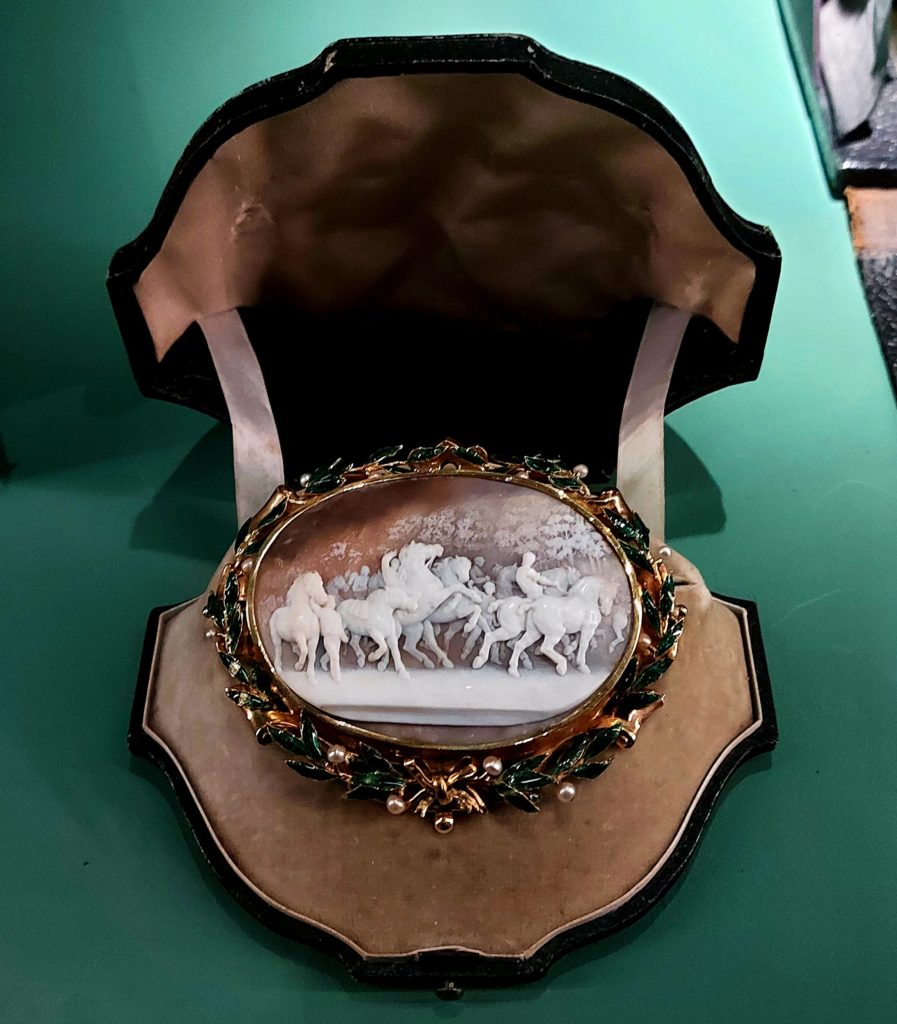

The Horse Fair brought her huge popular acclaim. In 1854 she was awarded this Camée broche from the City of Ghent in Belgium, depicting this painting.

Travelling

Only by seeing animals and men in the countryside and mountains was it possible to observe and discover their lives. How else could she express the essence of different terroirs, and the unique characteristics of specific animals and agricultural practices? Bonheur travelled mainly in France, in the Auvergne, Nivernais, and Les Landes. Later, she would often spend the winter season in Nice. The Pyrenees were also a major destination and there Rosa Bonheur could experience the majestic beauty of the mountains and study donkeys and sheep. She also travelled to Scotland, following in the footsteps of Sir Walter Scott, apparently one of her favourite authors. She enjoyed discovering Scottish breeds, and returned with studies which she would use throughout her life. Beautiful examples are: Highland Shepherd (1859) and Poneys of the Isle of Skye (1861).

Animal muses

After The Horse Fair, Bonheur became very successful and her fame stretched overseas. She was able to buy the Château de By in Thomery, on the edge of Fontainebleau forest. This isolated retreat in a rural setting allowed Rosa Bonheur to escape the countless visitors who sought her out in Paris. She had a large studio constructed next to the main building. In 1860 she moved in with Nathalie Micas and Micas’ mother who both took care of buildings and animals, so Bonheur didn’t have any practical concerns. The château was designed as an “Estate of Perfect Friendship” and “a true Noah’s ark.” Rosa Bonheur studied animals daily; she kept dogs, horses, and sheep as well as wild animals. Deer and boar were among her many models, friends, and muses.

This large painting she called King of the Forest (1878). It is both mysterious and majestic. The eyes of this deer are utterly mesmerizing. The animal gaze …

Around her château Rosa Bonheur could take long walks in the surrounding fields and forest in order to observe animals in their natural habitat. The artist dubbed her studio “the sanctuary.” It was the focal point of the By property, and it was a place of absolute freedom, the artist’s ultimate domain. Here, under the gaze of stuffed animals, she patiently developed large-scale canvases, alongside her work from life, which aspired to capture the vital spark of each animal.

I marvelled not only at the large paintings, but also at many smaller ones. I cannot include them all in this review, but this one from 1885, I cannot leave out: Toutou, the Loved One.

Practice makes perfect

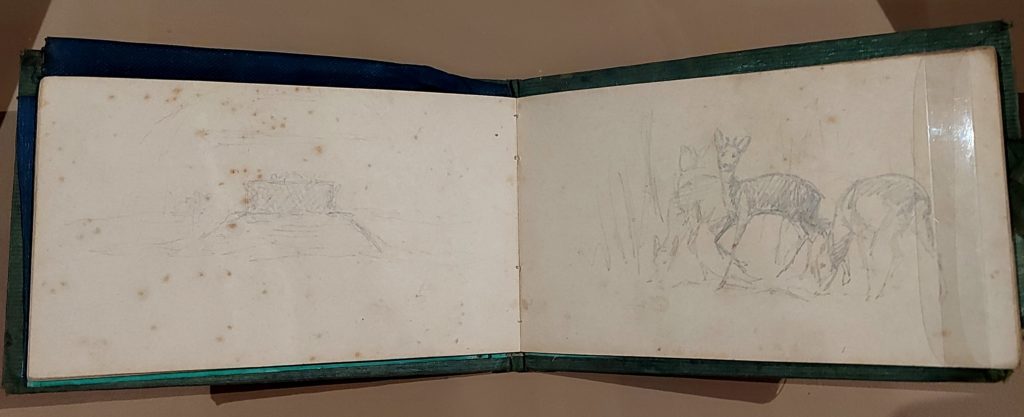

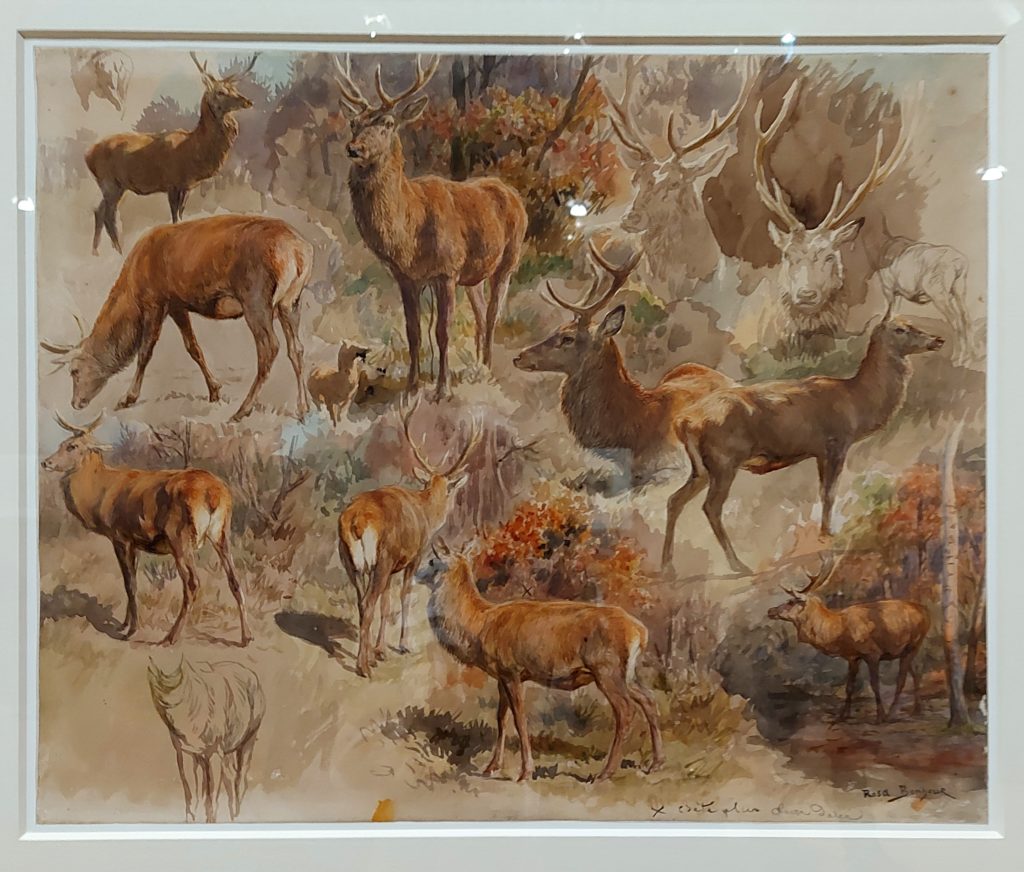

Not a day went by without a meticulous sketch of a deer’s stance, or a dog’s expression. Rosa Bonheur drew tirelessly, accumulating studies of details which she would juxtapose on large sheets of paper. Rosa Bonheur cherished her studies, in pencil, oils and watercolor alike. They formed the “vocabulary” on which she drew throughout her life to create new compositions. The organizers display many drawings and sketchbooks at the exhibition. Seeing them and being at such close distance of such work is beyond words …

At this exhibition I learned that she never painted anything without studying all aspects of the subject—in her case, animals. So look at the posture of this hunting dog: Barbaro After the Hunt (1858), absolutely exhausted after his day’s work.

Into the wild?

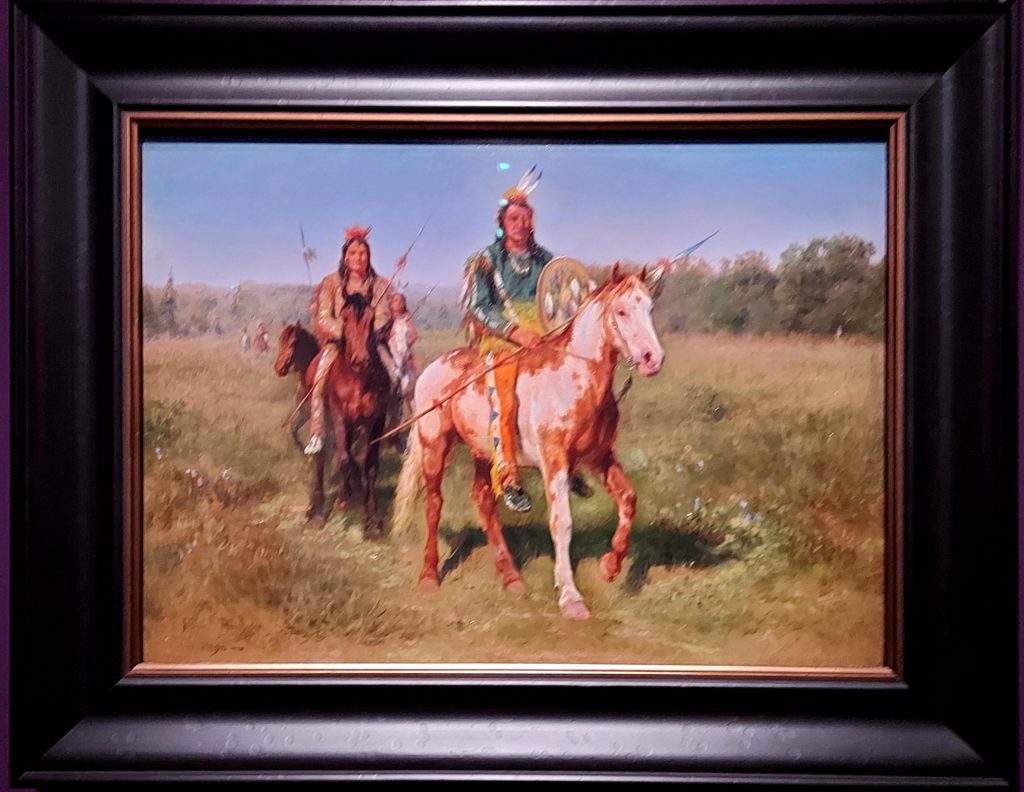

Rosa Bonheur had wanted to visit the USA, but she never did. So when Buffalo Bill came to Paris to put on a show in 1889, she was there to depict him as well as some Indians.

Bonheur never went to Africa either. Yet this painting made me sit and almost miss my

Thalys back to Amsterdam. She lived with lions; she studied their behavior together and dedicated many portraits to them. This (somewhat idealised) family she named The Lion at Home (1881). As far as I’m concerned, she might as well have named it The Royal Family.

I realize that I’m not doing Rosa Bonheur’s work, nor the inspiring exhibition, any justice by choosing only a few examples. Quite a few (well-known) portraits of Bonheur are also on display, including an 1898 portrait of the artist by her friend Anna Klumpke.

The exhibition Rosa Bonheur at the Musée d’Orsay runs until January 15, 2023. So if you have the opportunity—do go to Paris and visit this once-in-a-lifetime exposition. To me, all her exhibited works are masterpieces.

Ien G.M. van der Pol is the chairman of Fem Art Collection (follow on Twitter), a non-profit foundation that aims to collect and put “forgotten” female painters of the nineteenth century in the spotlight. Follow Ien on Twitter and/or connect with her on LinkedIn!

All photographs taken at the exhibition by Ien G.M. van der Pol.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Dr. Suzanne Singletary

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

More Art Herstory guest posts about 19th-century women artists:

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet: An Artist in Her Own Right, by Rebekah Hoke Brown

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Viola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman