Guest post by Stephanie Pearson, museums.love

In two of the smaller rooms in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, some thirty paintings have been assembled into a stimulating special exhibition about the artist Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), celebrating the 300th anniversary of the painter’s birth.

Like many women artists, her name is not as well known as that of her male contemporaries. This exhibition goes some way toward spanning the gap, presenting Therbusch as an astonishingly successful eighteenth-century artist despite many obstacles. It situates Therbusch in her social and artistic context, highlighting a few key moments and themes in her rich career. Ultimately it also leaves one wanting to know more—perhaps presenting an opportunity to expand on this remarkable Berlin figure in other media after the exhibition closes.

A slow start

The central concern of the exhibition is Therbusch’s artistic development. From humble beginnings as an innkeeper’s wife and mother of five, Therbusch could begin her artistic career in earnest only at age forty. But she did so with astounding success, considering the circumstances, and painted in numerous courts and academies across Western Europe.

The first three paintings (Figures 2, 3 and 4) that greet the visitor to the exhibition illustrate two aspects of Therbusch’s artistic progress. First, she learned in part by copying works by the Prussian court painter Antoine Pesne—the sort of painting she too would make into a career. Second, her paintings improved immensely over her lifetime. Although her 1745 copy of Pesne’s portrait of his daughter shows promise, her own original portrait (of a different sitter) from 1778 shows the fulfillment of that promise.

The marble-white but somewhat flat décolleté of 1745 has become by 1778 unquestionably living, breathing flesh. The studied creases and shimmers of fabric have become effortless and flowing. Pesne might have been proud to have his daughter portrayed by Therbusch’s mature hand. This set of paintings is a good introduction to the idea that Therbusch had talent early on, but could cultivate it to perfection only later in life.

Three further paintings flanking the entrance make clear that Therbusch’s artistic career didn’t spring from purely personal interest. Her family was in the business of painting. Her father, Georg Lisiewsky, painted portraits for the “Soldier King” of Prussia, Frederick William I—as did her older sister, Barbara Rosina, and her brother, Christoph Friedrich Reinhold.

The Lisiewsky family was talented in portraying just what members of the elite class were keen on showing off: symbols of their valor, wealth, and social status. As painters, they pay careful attention to medals and luxurious fabrics. With attributes and still lifes, they provide the layer of symbolism desired in such self-representations.

Shall I compare thee to…

Situating Therbusch in her artistic milieu, the exhibition compares her work to other great painters of the eighteenth century. She is said to paint silk like Gerard ter Borch, still life like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and the Dutch genre painters, flesh like Peter Paul Rubens. That Therbusch knew and studied such works is a reasonable assumption. The exhibition is right to point this out, and generally does not to go too far by trying to draw a direct line from certain works or artists to Therbusch’s own works. The link between ter Borch’s rendering of silk and Therbusch’s own in her self-portrait (Figure 10) is perhaps overstated, but succeeds at least in drawing attention to the process of learning by careful looking and copying. Therbusch’s artistic education—within her family, over her many travels, and especially during her time in Paris—is enough to account for her own techniques and talents.

A Berliner in Paris

Therbusch’s travels to Paris and acceptance into the Parisian Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture form one focus of the exhibition. Her first application to the Academy was rejected on the grounds that the submitted painting could not have been painted by a woman. In 1767, however, she was accepted (the meeting minutes are available online).

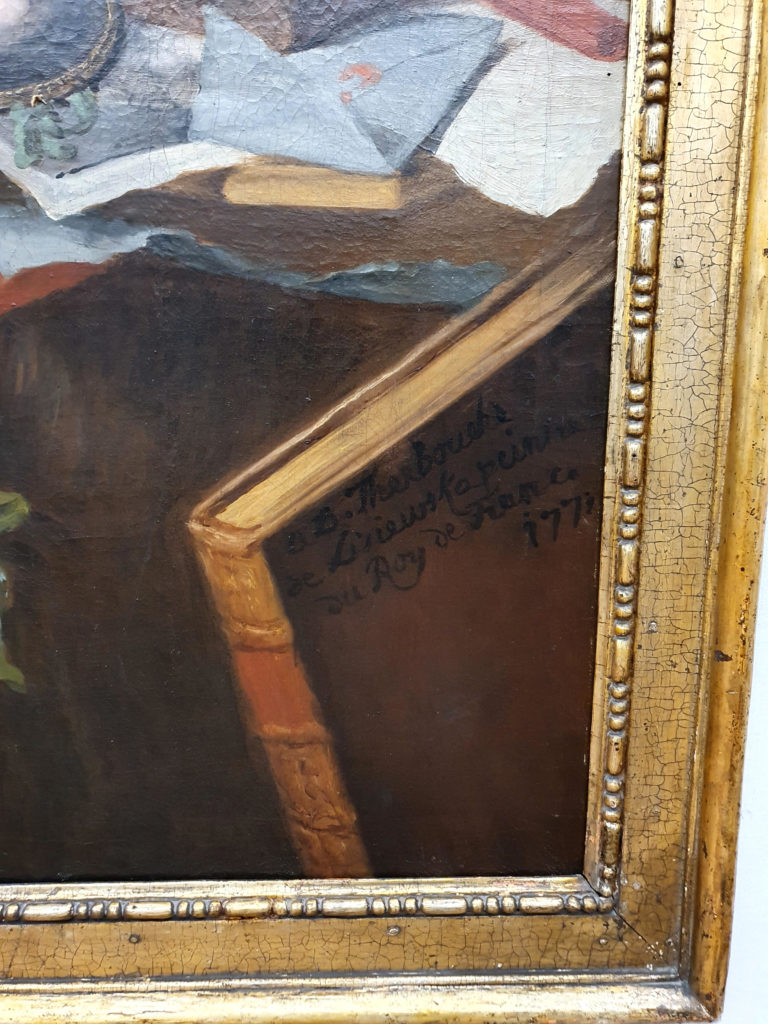

Being admitted was a feather in the cap of any artist of the day—but especially of a woman, as the Paris Academy set a cap of four female members (but did not strive to admit four if so many deserving talents were not to be found, as the meeting minutes record). Two of Therbusch’s portraits from 1771 in this exhibition include her signature as “painter of the king,” a designation accorded only to members of the Academy.

Not unique, but few

For comparison, the exhibition shows work by other women painters. Angelica Kauffman co-founded the London Academy around the same time that Therbusch entered the Parisian Academy. Anne Vallayer-Coster painted still lifes rivalling Chardin’s in Paris around the time that Therbusch was there. Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun painted family portraits for European courts around the same time. These comparisons are useful for showing us that women artists of this period could paint tremendously well, and even achieve accolades. But the assemblage also underscores how rare these successful women were compared to their many male contemporaries.

An Enlightenment woman?

Such a series of travels and achievements in academies across Europe is extraordinary, doubly so for a woman at that time. In some ways, it might be refreshing to see an exhibition that does not focus at every turn on the gender of a female artist.

Yet gender is one of the greatest obstacles that Therbusch overcame, as most evident in the Parisian Academy’s cap on women. Emphasizing this would seem fitting to her story, particularly because the Enlightenment of the show’s title was a largely male phenomenon. Fundamental Enlightenment values like rationality and liberty, developed through practices like writing lengthy texts and debating in coffeehouses during one’s leisure time, clearly corresponded more closely to a male reality than a female one. The exhibition’s subtitle, “A Berlin Woman Artist of the Age of Enlightenment,” prompts the question: To what extent can a woman be “of” the Enlightenment? That Therbusch’s career at all resembles that of a typical male Enlightenment artist is nearly incredible precisely because of her gender.

Hungry for more

While this exhibition offers an inspiring introduction to a remarkable woman, it leaves many questions unanswered. (A larger exhibition might not have been possible for logistical or financial reasons, but would have been a treat!) It is a shame that the exhibition has no accompanying publication. One might turn to the historical novel of Therbusch’s life that is cannily sold in the museum shop: Die Portraitmalerin, by Cornelia Naumann. Although embellished in the way of historical fiction, the book can offer some answer to the lingering questions about how Therbusch may have orchestrated her career trajectory, and how we can imagine her lived experience of it.

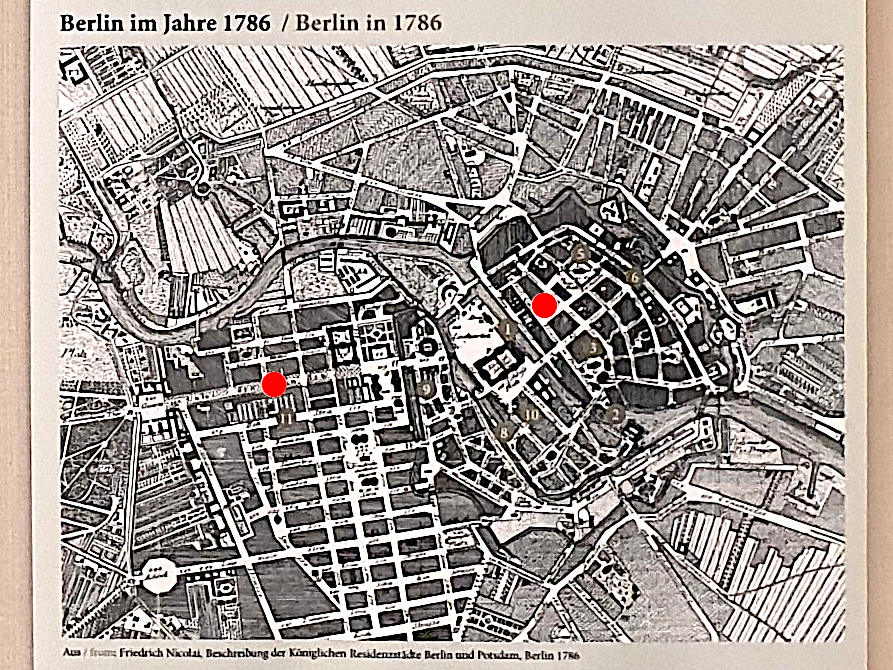

The Berlin-born Therbusch is a talent worth canonizing alongside Berlin’s other renowned scientific and cultural figures. Because the men in that canon are still more visible than the women, I would like to see this exhibition further instrumentalized to expand beyond that traditional view. One way to do this, even after the exhibition closes, would be to use the local geography to develop a short walking tour of Therbusch’s Berlin. Indeed, she lived and worked in what is now a very popular tourist area (shown on a small map in the exhibition): her studio was on the main street, Unter den Linden, and her husband’s inn was near the now-iconic TV tower. Therbusch’s impressive story deserves to be made visible in the central spaces of her city.

Dr. Stephanie Pearson has been teaching, researching, translating, and leading tours in the museums of Berlin for nearly ten years. She founded the project museums.love in order to share stories about museums and their collections in a way that’s as inclusive and vivacious as possible.

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Berlin Woman Artist of the Age of Enlightenment is on at Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie through April 10, 2022.

More Art Herstory posts to do with 18th-century women artists:

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Xavier F. Salomon

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Ann Golob

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Early Modern European Women Artists at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, by Erika Gaffney

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Jitske Jasperse

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Sheila McTighe

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni, by Sara Matthews-Grieco

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura