Guest post by Xavier F. Salomon, The Frick Collection

An Anniversary

April 15 marks the 264th anniversary of the death of the Venetian painter Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757). Rosalba lived her entire life in a house on the Grand Canal, near the parish church of San Vio—a home that would also become the workshop where she produced miniatures and pastels. Her last ten years, by which time most of her immediate family had died, were spent in isolation and darkness in the house. In the mid-1740s, she had begun to lose her sight, and a number of painful surgical operations did not manage to spare her from an artist’s worst fear: complete blindness. Her life before that, however, had been a successful one and an extraordinary one for a woman artist.

A Celebrated Artist

Little is known about Rosalba’s childhood and training. Her father was a lawyer and her mother, Alba Foresti, a celebrated lace maker. She had two siblings, her sisters Giovanna and Angela. By the time Rosalba was in her mid-twenties—in the early 1700s—she was so well known for her small miniatures on ivory that they reached foreign markets. Venice was an international center for merchants, as well as for visitors on Grand Tours—primarily from Germany, France, and Britain—and Rosalba produced miniatures for these foreign visitors. While the technique she used was much admired in the north, it was not common in Italy. Rosalba managed to capture a corner of the market that was of little interest to male painters at the time.

In 1705, at age thirty-two, she was elected to join the most prestigious artistic academy in Italy—the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. The British diplomat Christian Cole, a friend who had actively supported her nomination, wrote to her in March 1705 to tell her that she was to join as an academician. This was an exalted rank that had previously been occupied by a number of women artists, many of whom are famous today, others hardly known: Caterina Ginnasi, Laura Marescotti, Anna Maria Vaiani, Elisabetta Sirani, Lavinia Fontana, Giovanna Garzoni, Giustiniana Guidotti, Isabella Parasole, Plautilla Brini, Ippolita de Biagi, Maddalena Corvini, Lucia Neri, Teresa del Pò, Virginia di Verro, and Teresa Raimondi Velli. A few years later, in 1708–9, Rosalba’s self-portrait was included in the collection of renowned artists’ portraits assembled by the Medici family in Florence. There she appears as a pastel portraitist, probably in the act of portraying her sister Giovanna (1675–1738), who was also her main assistant.

A Pastel Painter

In the first decade of the 1700s, Rosalba started to move from painting in miniature to a new medium, one she would advance to new heights: pastel. She portrayed rulers and aristocrats who passed through Venice and sent her works to the courts of Europe. In 1720, she spent a year in Paris, where she met Jean-Antoine Watteau, and in 1723 she worked at the court of Modena. In 1731, she visited the imperial court in Vienna. A number of foreign rulers, beginning with the elector Palatine in Düsseldorf, tried to tempt her to move abroad, but Rosalba’s home remained firmly in Venice. She spent all her life in her birthplace but remained in contact with colleagues, patrons, and friends across Europe.

In 1985, Bernardina Sani, the Italian art historian who has most attentively studied the work of Rosalba, published two volumes of almost seven hundred letters to and from Rosalba, spanning the period between 1700 and her death. Rosalba’s diary of the 1720–21 trip to France also survives, together with a number of other documentary sources that allow us to understand the artist in a comprehensive way. Given this, it is all the more surprising that there has been no English language book devoted to the artist before Angela Oberer’s 2020 book The Life and Work of Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757): The Queen of Pastel. In one of Rosalba’s late self-portraits, now in the British Royal Collection, the artist appears as the “Queen of Pastel,” as she was known during her lifetime. She wears fur and jewels, and her clothing and hair are decorated with Venetian lace, which she was probably trained by her mother to make as a young woman.

Rosalba’s Works

Rosalba’s pastels are particularly fragile, and she constantly worried about their transportation and survival. Today, more than four hundred works by her survive in museums and private collections around the world.

The electors of Saxony (and kings of Poland) were among Rosalba’s most ardent admirers, and one hundred fifty-seven works attributed to her (both pastels and miniatures) were gathered in the so-called “Kabinett der Rosalba” in Dresden in the eighteenth century. Sadly, forty of them were lost (destroyed or gone missing during World War II), and another group was de-accessioned in the 1920s. However, with their collection of seventy-five pastels and a few miniatures, the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden is still the most important institution at which to marvel at—and study—Rosalba. Among their Rosalba masterpieces are her portraits of the singer Faustina Bordoni and of the mysterious blond man dressed in Turkish attire and holding a small porcelain cup.

The second largest number of pastels by Rosalba is in Venice, divided between the Gallerie dell’Accademia and Ca’ Rezzonico, for a total of about twenty works. Examples of her pastels can also be seen at the National Gallery in London, the Royal Collection, The National Gallery of Ireland, the Louvre, and the Hermitage. Not all Rosalba’s pastels are portraits. She was also well known for her allegorical paintings and often produced sets of Seasons, Elements, and Continents. When she joined the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris, on October 26, 1720, her reception piece depicted a mythological subject: a Nymph from Apollo’s Retinue.

Some of her most elegant allegorical and mythological pastels are, yet again, in Dresden, in particular, her 1746 series of the Elements.

(Left) Rosalba Carriera, Allegory of Air, 1746. Pastel on paper. Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. (Right) Rosalba Carriera, Allegory of Water, 1746. Pastel on paper. Gemäldegalerie, Dresden.

A few museums in the United States—both on the East Coast (in New York, Boston, and Washington) and West Coast (Los Angeles and San Francisco)—have pastels by Rosalba. The most spectacular one, and one of the artist’s masterpieces, is A Young Lady with a Parrot at the Art Institute in Chicago. It is unclear if this is a portrait of a specific individual—possibly an English sitter—or, instead, a fantasy figure. A Young Lady with a Parrot encapsulates the brilliance and sophistication of Rosalba’s work in her rendering of textures.

New Acquisitions for The Frick Collection

The collector Alexis Gregory, who died in 2020, bequeathed to The Frick Collection two pastels by Rosalba as part of a group of twenty-eight artworks. The Frick previously had no works by this artist, so it is particularly thrilling to be able to display her work through these two spectacular examples. The portraits depict an unidentified man and a woman. It is unclear whether they were Venetian or foreign patrons or whether they were in any way related. Rosalba did not often portray couples in pendant portraits, so it is likely that the sitters are unrelated.

The female portrait is typical of Rosalba’s work. The woman is elegantly dressed and sports jewels and flowers. The man, on the other hand, wears a pilgrim’s black cape and has a pilgrim’s staff next to him—an unusual costume that appears in one other portrait by Rosalba (in a private collection). Why is the man dressed as a pilgrim? Did he travel to a site of pilgrimage? Or is the costume a pun on the sitter’s surname (Pellegrini, Pilgrim, Pèlerin, Pilger)? The attire may be related to many figures in Watteau’s paintings, who appear as “pilgrims of love.” The inclusion of the typical black tricorn hat, however, suggests it is more likely that this was simply a costume for Venetian carnival.

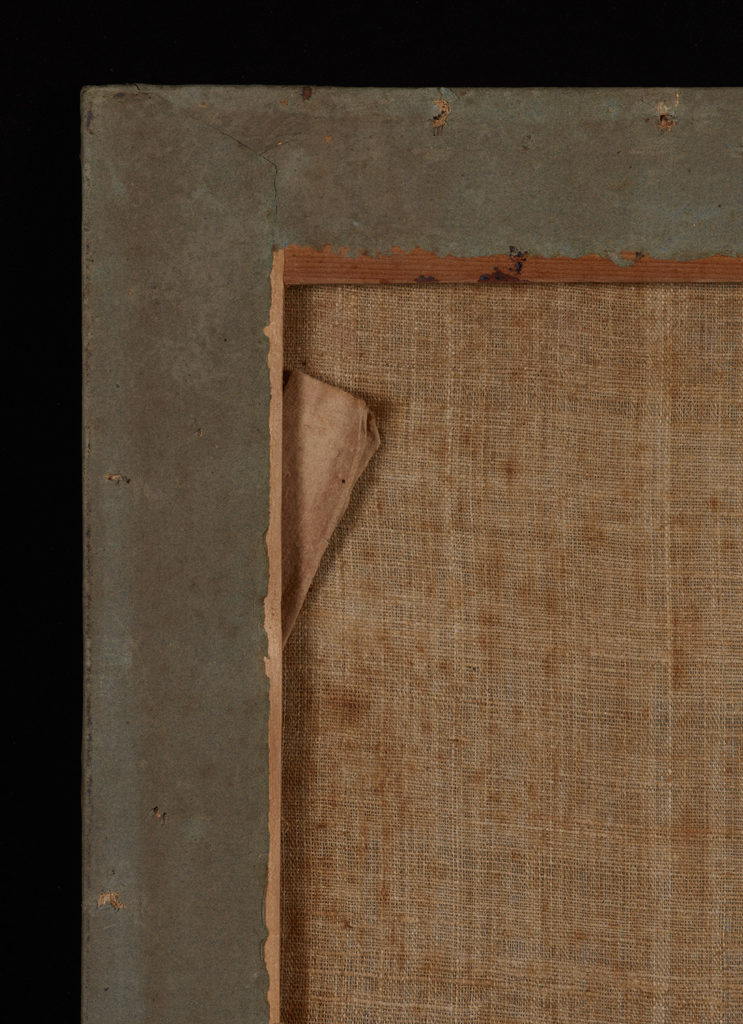

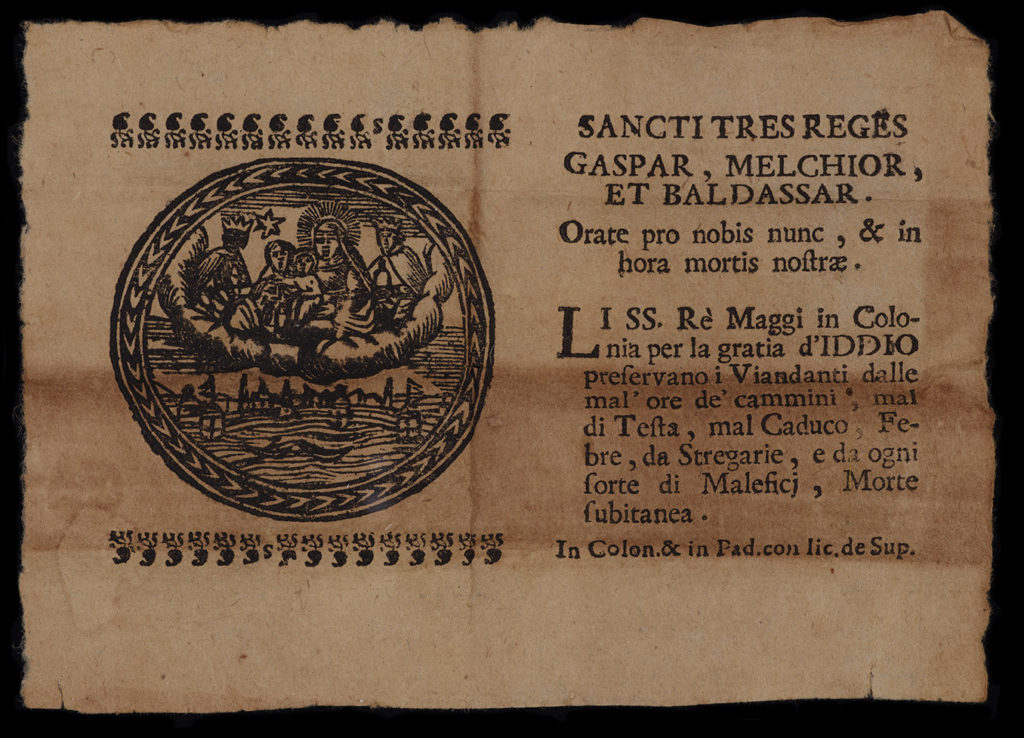

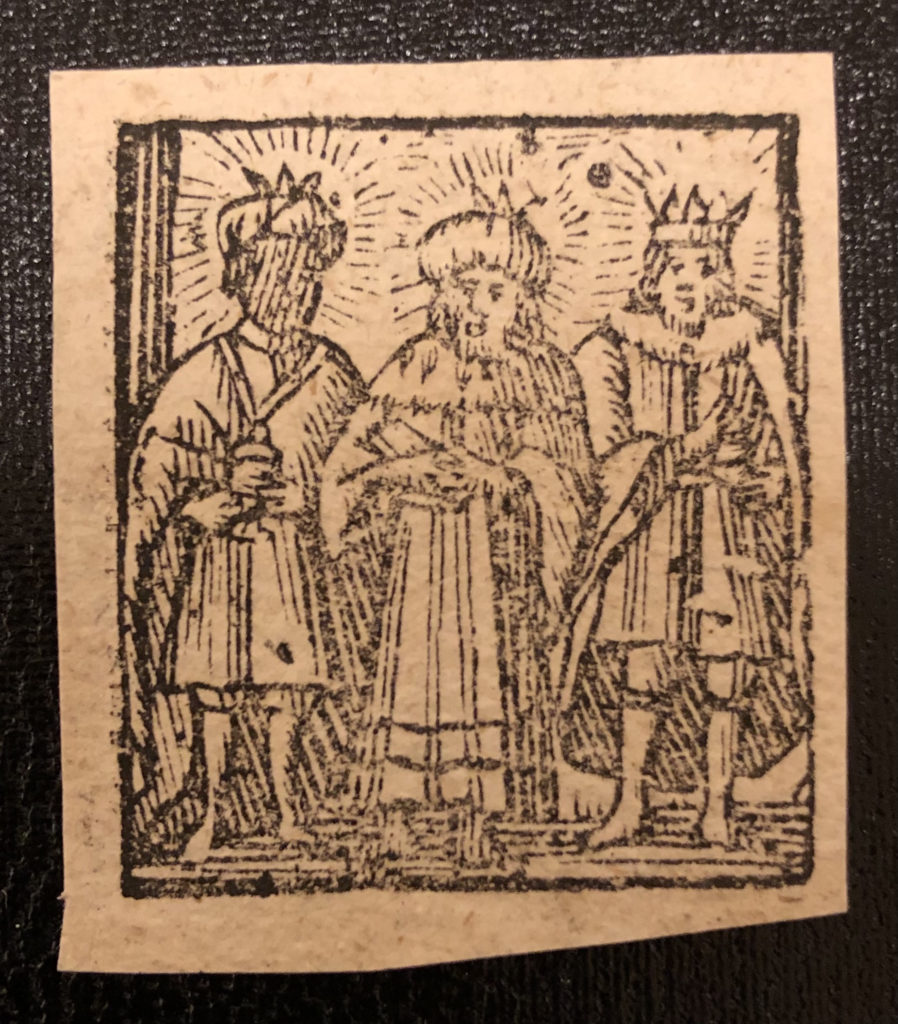

The Protection of the Three Magi

During the examination of the two pastels at The Frick Collection, a small religious image was discovered behind the strainer on which the paper of the work is laid over a canvas. It is a printed piece of paper showing the Three Magi together with the Virgin Mary over the city of Cologne, where the relics of the Magi are preserved. The accompanying text declares that the Magi (and this printed image) are meant to protect travelers against “bad times of travel, headaches, epilepsy, fever, witchcraft, any type of malefice, and sudden death.”

Rosalba is known to have had a particular devotion to the Magi, and she regularly included these images in her pastels. Examples of them have been found in Dresden, Venice, Paris, and at the Royal Collection. On December 3, 1729, Anton Francesco Marmi wrote to Pier Caterino Zeno of Rosalba’s devotion to the Magi, saying that Rosalba “is particularly devoted, and dedicated to charitable acts; and she has a distinct devotion for the Saint Magi… once she entrusted me with a certain portrait to send to my brother in Vienna; and she gave me a little sheet of paper (cartuccia) of the three aforementioned Magi in adoration; and she told me that she recommends the safe travels of that portrait to them; adding that whenever those little images accompanied her paintings, they always arrived safely.”

I have become very interested in these small devotional images (santini in Italian and Dreikönigszettel in German) and am currently studying their use by Rosalba. I have been able to examine a number of pastels by Rosalba in museums and private collections and will soon be traveling to Venice and Dresden to gather more information. Shortly after examining the Frick’s Portrait of a Man in a Pilgrim’s Costume, I asked the Metropolitan Museum if I could study their Gustavus Hamilton, Second Viscount Boyne, in Masquerade Costume. Marjorie Shelley (head of the Paper Conservation Department), Associate Curator David Pullins and I found another santino hiding under the strainer. In the next few months, I hope to study more pastels by Rosalba with a view toward publishing an article on this unusual and fascinating practice.

Death in Venice

On December 19, 1756, four months before her death, Rosalba drafted her final will. She intended to “distribute the little wealth that Our Lord allowed me to gain through my work in painting.”

Her fortune was, in fact, considerable. She left almost ten times more money than Canaletto was to leave at his death a decade later. She left funds for her funeral and asked to be buried in the same tomb as her sister Giovanna, in the church of San Vio, near her house. Her younger sister, Angela, widow of the painter Antonio Pellegrini, was to be her main heir, after a number of personal bequests and charitable donations. The church of San Vio was demolished in 1813, and no trace remains of the Carriera family tomb. Rosalba’s pastels and miniatures bear witness to the extraordinary talent of a successful and brilliant artist, who was an international celebrity during her lifetime.

Dr. Xavier F. Salomon is Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator at The Frick Collection, New York. He was previously Curator of Southern Baroque in the Department of European Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Arturo and Holly Melosi Chief Curator at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London. He is an expert on Italian art from the 16th to the 18th centuries, and especially of the artist Paolo Veronese (1528–1588). He curated the monographic exhibition on the artist at the National Gallery, London (2014), as well a number of other exhibitions on artists such as Bertoldo di Giovanni, Salvator Rosa, Cagnacci, Van Dyck, Murillo, Tiepolo, Goya, Valadier, and Canova. In 2018, he was nominated Cavaliere dell’Ordine della Stella d’Italia by the Italian President of the Republic. He is currently preparing the catalogue raisonné of Veronese’s drawings and a catalogue of the Frick’s Spanish paintings.

Visit Art Herstory’s Rosalba Carriera resource page, here.

More Art Herstory guest posts about eighteenth-century women artists:

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Dr. Christina K. Lindeman

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, Guest post by Dr. Angela Oberer

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, Guest post by Dr. Jessica L. Fripp

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, Guest post by Dr. Anita V. Sganzerla

More Art Herstory posts about Italian women artists:

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, Guest post by Jacqueline Thalmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, Guest post by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, Guest post by Dr. Babette Bohn

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, Guest post by Dr. Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Truly amazing post. R. David Weaver