Guest post by Jesse Locker, Portland State University

Though plagued with delays, lockdowns, and closures, the Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition at the National Gallery in London, which closed in January 2021, marked a transformation in the general public’s understanding of—and appreciation for—the artist. Thanks to the capable organization of curator Letizia Treves, the general public finally received a proper introduction to Artemisia. Featuring thirty-six high quality and largely uncontroversial works by the artist, the exhibition justifiably earned rave reviews from critics. Artemisia was particularly in need of such a tightly focused exhibition because some previous shows have been marred by the inclusion of dubious attributions, works in very poor condition, or “test cases” that made it difficult to perceive a unified body of work.

But the interests of art historians are not always the same as those of curators. Despite its undeniable success, a wrinkle-free exhibition can give the impression that there are not still areas of controversy, uncertainty, and debate in an artist’s work. Exhibitions are limited to the most characteristic and highest quality works in the best condition. This means by definition that they won’t include many works that are atypical, in less-than-perfect condition, unable to be lent, or simply don’t fit a particular story. In the case of Artemisia, there have been so many new works discovered in past decades—some even since the exhibition was first announced—that her oeuvre keeps expanding.

In this post I showcase some recently discovered works that for one reason or another were not in the London show, but which I believe nevertheless shape our understanding of the artist.

Artemisia as Religious Painter

We tend to associate Artemisia with portrayals of powerful ancient heroines. So it is easy to forget that many of her works, even if not the most celebrated ones today, are religious paintings. In 1968, R. Ward Bissell even went so far as to suggest that the libertine Artemisia preferred to paint “scenes that did not require her to acknowledge the presence of Divinity.” But a significant number of the new discoveries suggest that she was famous in her own time to a large extent because of her treatment of traditional religious subjects.

Christ Blessing the Children

One of the most interesting rediscovered works is Christ Blessing the Children (Fig. 1; San Carlo al Corso, Rome). In 2001, based on an old black-and-white photograph from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Riccardo Lattuada attributed it to Artemisia. But it had been deaccessioned in 1979, under an attribution to Carlo Rosa, and no one knew where it had ended up. However, in 2012, Gianni Papi came across it in the church of San Carlo al Corso in Rome—though exactly how it got there remains a puzzle. Recent restoration revealed the artist’s signature on the back, and a date of 1626.

It is now clear that this is the painting, known from documentary sources, that Spanish noble the Duke of Alcalá commissioned from Artemisia in Rome for the charterhouse of Santa María de las Cuevas in his native Seville. The painting was made for an “Apostolado”—portraits of the 12 disciples painted by “the most renowned [painters] that were to be found in Italy”—with Artemisia’s Christ Blessing the Children at the center. With its devout and traditional subject matter, this painting does not fit out usual expectations of Artemisia’s oeuvre. Further, it was clumsily restored at some point (what appears to be wool in the bottom of the picture was originally a dove). In its day, however, the painting was famous throughout Spain, and copies made for the cathedrals of Granada and Zamora are still in situ.

Christ and the Woman of Samaria

Another painting with a biblical subject that was previously known only from documentary sources is Christ and the Woman of Samaria (Fig. 2; private collection). In a letter she wrote from Naples on November 24, 1637, Artemisia told her patron, the papal secretary Cassiano dal Pozzo, that she was working on a painting of “the Woman of Samaria with Christ and the twelve apostles in a distant landscape.” Rediscovered in a private collection in 2007, the painting is a large and ambitious one, portraying Jesus and the Samaritan woman seated on opposite sides of the well, absorbed in conversation. The tiny disciples mentioned in her letter can be seen over Christ’s shoulder, emerging from the walled city in the background. With its ochres, purples, blues, and reds, the painting shows the boldness of color, monumental scale, and use of landscape that become characteristic of her works in Naples in the later 1630s.

David with the Head of Goliath

One of the new discoveries that has garnered the most publicity is a monumental David with the Head of Goliath (Fig. 3). This painting shows the young David at rest, looking defiantly at the viewer with legs crossed and his arm resting on a sword. Under him sits the large, bloodied head of Goliath. The work originally went up for auction as an anonymous Caravaggist—perhaps Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri—but the auction house changed the attribution to Artemisia at the last moment (though too late for the bidding to build up any momentum).

Upon cleaning, the artist’s signature was revealed, painted in a dramatic red on David’s sword. Inventory references tell us that Artemisia painted this subject at least three times: in Rome, Naples, and London. Stylistically, it shares a great deal with Christ and the Woman of Samaria. But its composition seems to depend on a Domenico Fetti painting of the same subject in the collection of Charles I of England (Fig. 4). Therefore, it seems likely the artist painted it during her sojourn in London ca. 1638-39, though this dating is by no means secure. Nevertheless, like the other newly discovered works, it shows her range went well beyond the typical representations of vengeful or victimized women.

More Roman Heroines

In addition to these new works with religious subjects, a few of the paintings that have come to light recently, though closer to what we might expect from Artemisia in terms of subject matter, still raise questions about her artistic development and the chronology of her oeuvre.

Lucretia in Venice

Perhaps the most exciting is the beautifully preserved Lucretia (Fig. 5; Matthiesen Gallery, London), which sold for the record price of $5.2 million. It portrays the ancient heroine amidst a swirl of drapery, eyes turned upward, a dagger pointed to her breast. The painting has such close stylistic and compositional affinities with the figure of Esther from Artemisia’s Esther Before Ahasuerus (Fig. 6) that it seems likely that this work too was painting during the artist’s time in Venice (c. 1626–30).

On March 30, 2021, the J. Paul Getty Museum announced that it has acquired the Artemisia Gentileschi painting of Lucretia shown above.

It may in fact be the famous work praised by an anonymous Venetian poet, recorded in a 1627 manuscript as “Lucretia Romana, Opera della Sig. Artemisia Gentileschi Pittrice Romana in Venetia” (“the Roman Lucretia, work by Sig. Artemisia Gentileschi, Roman painter in Venice”). In one poem, the author chastises the painter for cruelly bringing Lucretia back to life only to let her die again, writing, “Pinge il caso Artemisia, e lo rinova…Hor più del ferro il suo pennel t’uccide” (“Artemisia paints the event and brings it back to life… Now more than the knife, it is her brush that kills you”).

Lucretia in Naples

Lucretia was a subject that Artemisia returned to with some frequency. A later variation (Fig. 7) sold in 2018 for over $2 million. Compared to the Matthiesen painting, this one is more idealized, and features a more expansive, three-quarter length composition. Likely painted in Naples, some parts of it seem to indicate the hand of Onofrio Palumbo, the assistant she sometimes employed in her later years, which would suggest a date in the 1640s. However, other areas, such as the beautifully embroidered hem of Lucretia’s garment, seem to be fully by Artemisia. Unfortunately, since the auction there has been no sign of the painting. It is not clear whether it ended up in a public or private collection.

Roman Charity

Finally, one of the most shocking pictures for modern audiences may be the so-called Roman Charity (Fig. 8). The painting, likely from the 1640s, illustrates the peculiar ancient Roman story of Cimon and Pero. According to Valerius Maxiumus and other sources, the elderly Pero was sentenced to death by starvation in prison; but, while visiting him, his daughter Cimon secretly breastfed him to keep him alive. Although in the artistic tradition the story often bordered on the pornographic, it was intended to be understood as a model of filial piety and Christian charity. For example, Caravaggio included it in his Seven Acts of Mercy to illustrate two charitable acts: feeding the hungry and visiting prisoners. Artemisia’s version, likewise, buried in deep black shadows evocative of Giambattista Caracciolo, is modest in its treatment. The artist communicates Cimon’s tentativeness as she keeps an eye out for a guard. She likely painted the work for Giangirolamo II Acquaviva d’Aragona, Count of Conversano, as it appeared in the 1666 inventory of his Norman-era castle in the southern Italian region of Bari.

As we can see from just this small selection, unlike established “Old Masters” such as Raphael, Caravaggio, or Rembrandt, Artemisia’s works are still being rediscovered with astonishing frequency. And this is not to mention the abundance of new archival and documentary findings. On the basis of these continuing discoveries, it is likely that in another decade we will have an entirely different understanding of the artist.

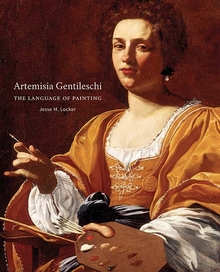

Dr. Jesse Locker is an Associate Professor of Art History at Portland State University who has written widely on early modern Italian art. He is a member of the editorial board for the Lund Humphries book series Illuminating Women Artists. His book Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting (Yale University Press, 2015) is now out in paperback. Follow Jesse on Facebook and Twitter.

Interested in learning more about Artemisia? Visit the Art Herstory Artemisia Gentileschi resource page!

More about Artemisia Gentileschi:

Exhibiting Artemisia Gentileschi; From the Connoisseur’s Collection to the Global Museum Blockbuster, by Christopher R. Marshall

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on Feminist Art History in the Wake of Artemisia: Vrouw & Macht at Rijksmuseum Twenthe, by Dr. Jitske Jasperse

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

“Artemisia” at the National Gallery: A Review, by Dr. Sheila McTighe

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Talking Artemisia Gentileschi with Joy McCullough, Author of “Blood Water Paint”

New from Art Herstory: The Artemisia Gentileschi Christmas Card

Art Herstory Resource Page: Artemisia Gentileschi

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome, by Alessandra Masu

The Restoration of Royalty: Lavinia Fontana’s Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, by Dr. Aoife Brady

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Dr. Loretta Vandi

Giovanna Garzoni’s Portrait of Zaga Christ (Ṣägga Krǝstos), by Dr. Alexandra Letvin

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Dr. Cecilia Gamberini

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Dr. Babette Bohn

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

A Tale of Two Women Painters (Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura)

Trackbacks/Pingbacks