Guest post by Angela Oberer

Art historians have documented the growing market of eager art lovers and collectors seeking to buy sensually and erotically charged images by the end of the seventeenth century. Still, it remains a somewhat puzzling fact that, as a woman artist and a respectable single lady, Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) indulged in what was a potentially dangerous theme for her public reputation.

Erotic art without a whiff of scandal

Considering the difficulties and obstacles she had to face and overcome in one way or another simply to become a female painter, the care with which she had to move in professional circles and the sly strategies she had to use to succeed, this choice to depict subjects that carried certain risks—on a private just as much as on a public level—should by no means be taken lightly.

Thus, it is all the more remarkable that Carriera appears to be the first professional female artist of international renown who dared to regularly depict pieces of erotic art. And—even more surprising—we do not have any clear indications of any kind of scandal regarding the eroticism in her works. None of her contemporaries seemed to have stirred up malicious gossip of any consequence. Instead, within the artist’s personal correspondence we find references by clients who praised her works and did not feel at all uncomfortable talking about an erotic piece of art she made. Here I present just two fascinating examples of these rare and revealing documents.

Giorgio Maria Rapparini’s response

Giorgio Maria Rapparini (1660–1727), the poet and secretary of Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm (1658–1716) in Düsseldorf, openly acknowledged his pleasure when he looked at the pastel he had just received. On 17 February 1718 he wrote:

Healthy and rubicund and with a mien from Paradise, this most delicate pastel has arrived—not in any way fatigued by the trip and without suffering in the least. Nor has any harm come to the bouquet of flowers in her hand, nor even to the beautiful nudity of her breast from the vigorous cold of the season.

His enthusiasm regarding the image, which he treated like a real human being, led him to describe the rejuvenating effects of the painting. And he revealed his physical reactions while admiring her.

Oh what a beautiful Virgin. This appearance has made me—a man over forty—feel again the sting of love’s arrow. I was expecting a beautiful thing, yes, but not a miracle, a marvel, a Paradise. I am sure that when our little son sees her and runs desirous to that teat, far fresher than the one he has just left, why then will I acknowledge my son! This has to be his heritage and his legitimacy when he will be grown-up.

No words seem to be enough to express the frenzy that elevated not only his spirits but also his desires:

Oh, what a taste! Oh what touches! Oh what harmony! Oh what hues of colour! Oh what outlines not outlined! Oh what features! Oh what purity! What nobility, what mastery! I could make a hundred living ones and still not be able to make something like this, that has life and blood running through her veins.

The use of the accentuating anaphora and the numerous exclamation marks highlight his alleged difficulty putting into words the sensations Carriera’s miniature evoked. The rhetorical tone of his lines reflects his awareness of the general notion held until at least the first half of the eighteenth century: To be aroused and transported by art (or literature) was a sign of superior sophistication. This intense experience typically led to a blurring of the boundaries between life and art, body and mind. To own this painting was not only to possess a piece of art, but for that piece of art to possess a life of its own.

The passion awakened in Rapparini culminates in the wish to come together with his wife as soon as possible, first to make her look at the painting and then, with her remembering every part of it, to produce their next child. And the child’s beauty would be influenced by the glorious piece of art. It was common belief since antiquity that if pregnant women looked at beautiful things or edifying art, the fetus in their womb had a better chance of being of a gentle nature, and beautiful as well. In this understanding, he wrote to Carriera that he had decided to hang it in the bedroom, right “next to the bed, that she [his wife] may grasp this form in her mind, now that we are imminently about to undertake the manufacture of our tenth puppet.”

Rapparini’s remarks reflect not only a fascinating openness towards Carriera as far as his reaction to one of her pieces is concerned, but also a popular belief that had survived since antiquity. It was generally held that a pregnant woman’s or a mother’s imagination was entangled with art and desire, that the imagery she looked at influenced the outcome of the child. Allegedly, Empedocles (495–444 BCE) in a lost text had formulated that “progeny can be modified by statues and paintings that the mother gazes upon during her pregnancy.” And more specifically, he maintained, like Rapparini himself, that it was through the woman’s imagination during conception that children were formed.

The reaction from Louis Vatin

Another fascinating example of a buyer’s intense reaction to Carriera’s art is found in a letter from French art collector Louis Vatin, in which he mingled personal physical longing with references to ancient mythology. On 10 September 1701, he wrote to the artist to remind her to consign a miniature depicting a figure of Venus to her colleague Antonio Balestra (1666–1740), who would personally deliver the piece to Vatin. [Note: in both cases discussed in this post, we do not know which exact artwork is described in the correspondence.]

To express his admiration for Carriera and her expertise, he included a poem that reads as if from an enamoured Pygmalion. In front of a voiceless but irresistible piece, the work of art comes alive in the imagination of literally an “amateur.” The mythic sculptor and the French art collector both enhance their desire by the touch of their beloved piece. Both awaken this lifeless piece of art to turn her into a living creature.

This letter also takes notice of the common debate since the Renaissance regarding the relationship between nature and art. In stating that the painted Venus surpasses la belle nature,Vatin begins with a minute description of the goddess’s face, using metaphors and vocabulary to emphasize the exciting sensuality that Venus emanates, only to collapse into a confession of his strong reactions. They can be read on both an emotional as well as a physical level. The climax of the poem states that the epitome of the author’s fantasy and desire, which he promises will extinguish any other craving and need, is to literally possess her. At the same time Vatin makes sure that his praise of the goddess corresponds in intensity to his praise of the artist, for it was she, virtuous lady, who made Venus after herself, a perfect work of art.

I feel again the violence of a curious desire, my charming mute with coral lips, on the shore of a stream, of a liquid crystal, your divine attractions I will enjoy and, even if you can neither see nor hear me, Venus, oh beautiful Venus, from the bottom of my heart I tell you, she who formed you, being a woman of virtue, a perfect masterpiece, she made you after her wish and mine, and when upon my return, I can possess you, I could never, oh beauty, ever desire else.

Apart from the canonical comparison between art and nature, which presumed that the epitome of artistry was to surpass nature, and apart from the equally topical, even if indirect and personalized reference to the Pygmalion myth, Vatin’s lines, written from a man to a woman, are striking for two other reasons. First of all, he gives a female artist a godlike role as creator, a role generally reserved to men. And second, Vatin expresses a surprisingly direct and personal accolade.

Conclusion

It is because Carriera decided (in 1700) to collect her correspondence that we have access to these significant documents. They provide a unique window into the relationship between male clients and a woman artist. And they might be the earliest extant examples of clients celebrating erotic art by a female painter.

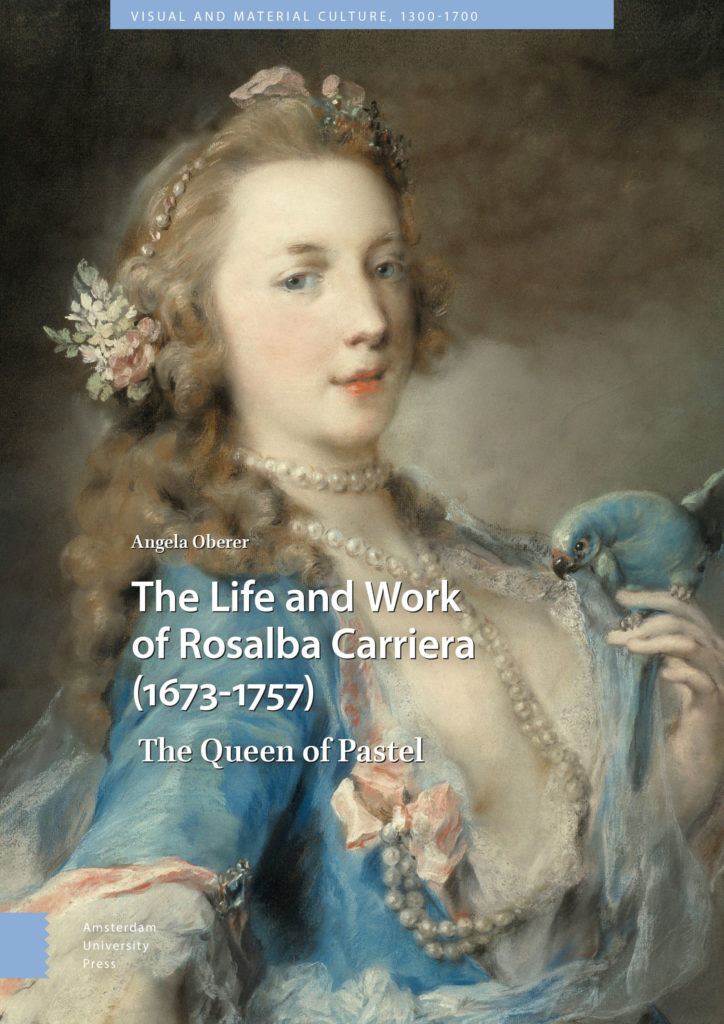

Dr. Angela Oberer has taught art history at Georgetown University, Florence; American Institute of Foreign Studies; CEA Florence; CET (associated with Vanderbilt University); and other programs that work with US colleges and universities. Her recent book The Life and Work of Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757): The Queen of Pastel, published by Amsterdam University Press, has been reviewed in Royal Academy Magazine and Hyperallergic. This blog post is distilled from two of the book’s chapters.

Visit Art Herstory’s Rosalba Carriera resource page, here.

More Art Herstory blog posts about Italian women artists:

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi, by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Dr. Xavier F. Salomon

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), Guest post by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion”, Guest post by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, Guest post by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, Guest post by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, Guest post by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Warp and Weft: Women as Custodians of Jewish Heritage in Italy, Guest post by Dr. Anastazja Buttitta

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus

A Tale of Two Women Painters, Guest post / exhibition review by Natasha Moura

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, Guest post by Dr. Katherine McIver

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann

Thank you! Considering the subject, I hesitate to say how much I enjoyed reading this.