Guest post by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Senior Curator and Department Head of Prints, Drawings & Photographs, Baltimore Museum of Art

In 2020, as part of a year-long institutional initiative to purchase only art made by women, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) acquired two delicately rendered opaque watercolor paintings of flowers on parchment by the German artist Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706–1783): Blue Morning Glory and Narcissus (ca. 1760, BMA 2020.3 and 2020.4, figs. 1 and 2).

Like many of her female contemporaries, Dietzsch remains relatively overlooked in the mainstream narrative of European art, despite the recognition she enjoyed in her own lifetime as a flower painter and the presence of her works in museums throughout the United States and Europe. Significant caches of Dietzsch’s depictions of both flowers and fauna can be found primarily in German museum collections—such as the Staatliche Museum zu Berlin, Germanisches National Museum in Nuremberg, Städel Museum in Frankfurt, and the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München—but stand-out examples are also found within the collections of the British Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, the Rijksmuseum, and a handful of American institutions, including those referenced below.

On the occasion of Dietzsch’s birthday (September 22), this post offers an opportunity to celebrate her work and share some insights on their technique and historical context.

Barbara Regina Dietzsch for the BMA

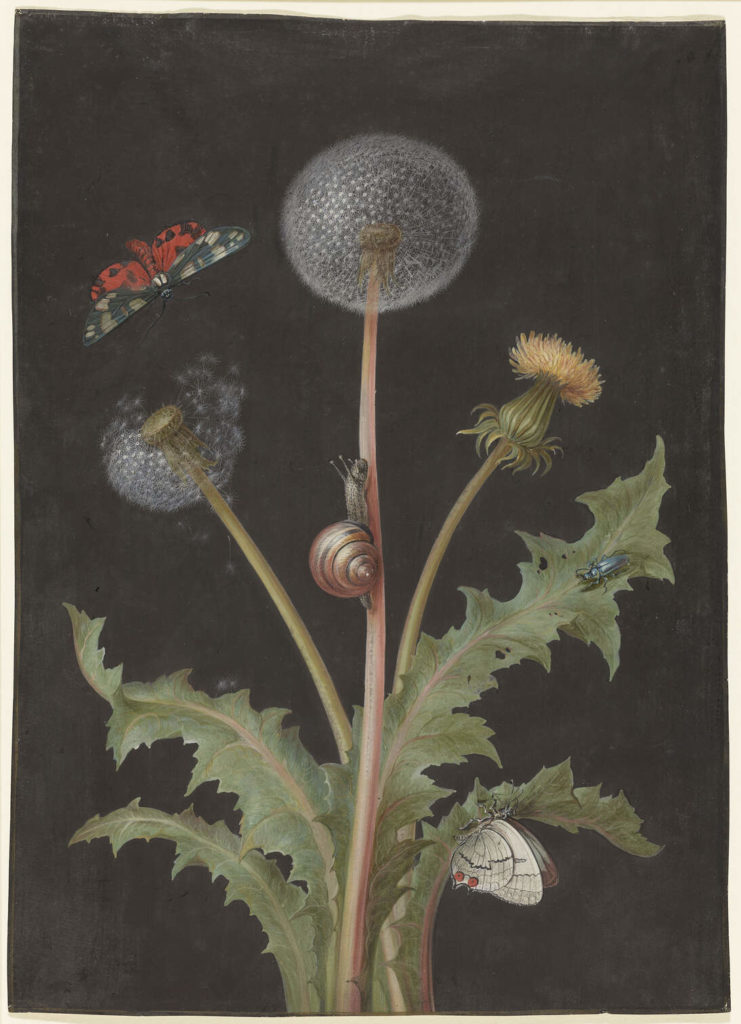

The two recently acquired watercolors—the first examples of Dietzsch’s work to enter the BMA’s collection—demonstrate the careful observation and delicate manipulation of opaque watercolor (gouache) typical of her mature work. The artist poses individual flowers against a solid black background, with each aspect of their petals, leaves, stems, and accompanying insects portrayed in extraordinary detail. Insects enliven the flowers: a red checkered beetle and a blue butterfly create a triad of primary colors with the yellow center of the Narcissus, and a golden orange moth alights onto the very edge of the Blue Morning Glory’s lower leaf, trailing barely perceptible wisps of web (or air?) still in motion (fig. 3).

The devotion to detail and the absence of any identifying inscriptions suggest that these drawings were intended for private contemplation and enjoyment, rather than to satisfy solely analytical aims. Smaller than a sheet of notebook paper, these flower portraits likely were kept in an album of collected drawings that would protect them from fading due to light exposure. A gold border—less assuredly applied at the edge of the sheets, probably not by the artist herself—further supports the assumption that they were collector items, valued both for their beauty and their reflection of the artist’s reputation as an accomplished flower painter.

The Dietzsch Family of Artists

Like generations of successful artists before her, Dietzsch grew up in an artistic family. Her father Johann Israel Dietzsch (1681–1754) was a landscape painter and engraver active in Nuremberg, who taught Barbara Regina the skills she needed to become a professional artist. Her six siblings also participated in the family workshop, including her sister Margaretha Barbara (1726–95), who Barbara Regina taught to paint natural subjects (fig. 4). In this regard, Dietzsch’s artistic formation and practice are not particularly remarkable. Generally speaking, women trained and working within a family structure were able to navigate more easily through the societal restrictions imposed upon them.

Dietzsch remained with her family in Nuremberg throughout her life, declining an invitation to become a painter at the archducal court of Bavaria. Alongside her siblings, several of whom were known to create similar works, Dietzsch worked as the principle flower painter and enjoyed the broadest reputation and accolades [Eyke Greiser, “Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706-1783) und ihre Familie “Gemälde auf Pergament”—Präsentationsformen und Markt,” in Maria Sibylla Merian und die Tradition des Blumenbildes von der Renaissance bis zur Romantik. Munich, 2017, pp. 205–219]. Christoph Jakob Trew (1695–1769), a physician and major figure in the botanical community of Nuremberg, referred to Dietzsch in the preface to his publication Plantae Selectae (1750) as “our countrywoman, Miss Barbara Regina Dietzsch, now quite famous everywhere.”

Dietzsch was born the year before Nuremberg established its first art academy, eventually abandoning the centuries-long tradition of artists training within an apprenticeship and guild system. Officially, women continued to be excluded from these formal arenas of education and exchange (since 1596 the Painter’s Code expressly prohibited women from producing paintings [Heidrun Ludwig, “Nürnberger Blumenmalerinnen un 1700 zwischen Dilettantismus und Professionalität,” Kritische Berichte 4 (1996): 21-29]). But domestic commercial activity—such as the workshop in the Dietzsch home—allowed for greater latitude in female members’ involvement.

Nuremberg and Natural History

A nexus of the printing industry, commerce, and learning, eighteenth-century Nuremberg long had been the site of robust investigation into the natural world, continuing a tradition that had been established during the Renaissance in both artistic and scientific circles. The profoundly detailed depiction of The Large Piece of Turf by Albrecht Dürer (1503) straddled both of these worlds, framing careful empirical observation within an aesthetically engaging composition. Hans Hoffmann’s irresistible watercolors of fauna, such as his Red Squirrel (1578), further popularized this hyper-veristic approach to capturing the likeness of nature rather than simply documenting it.

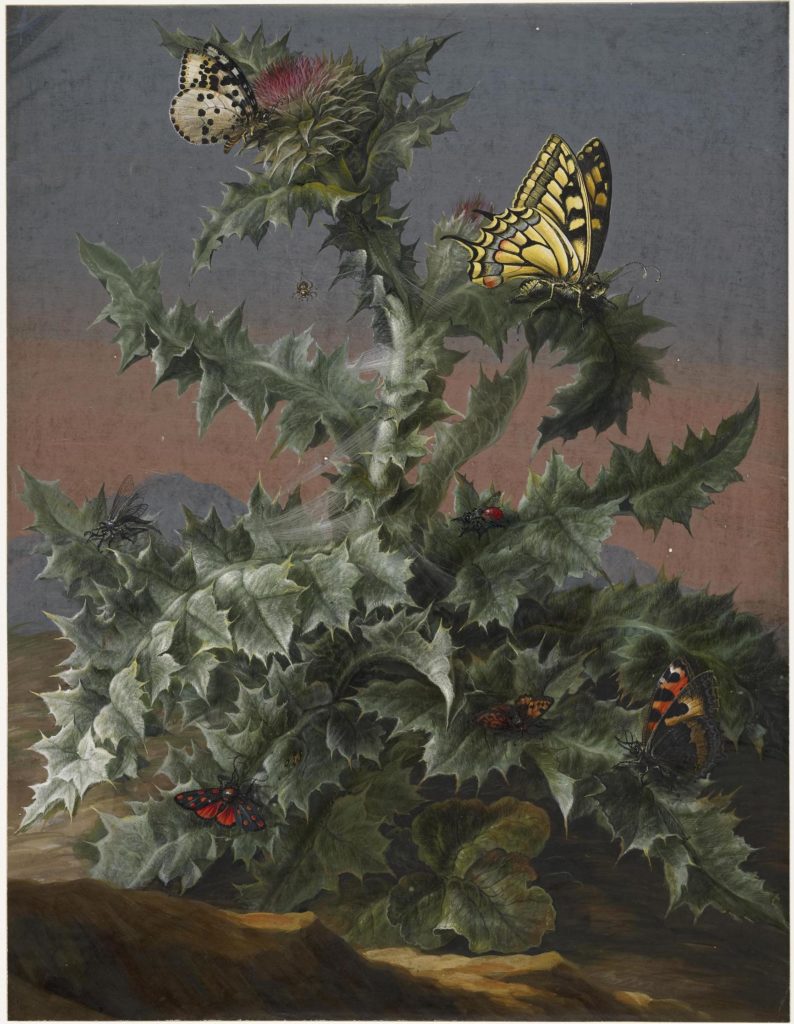

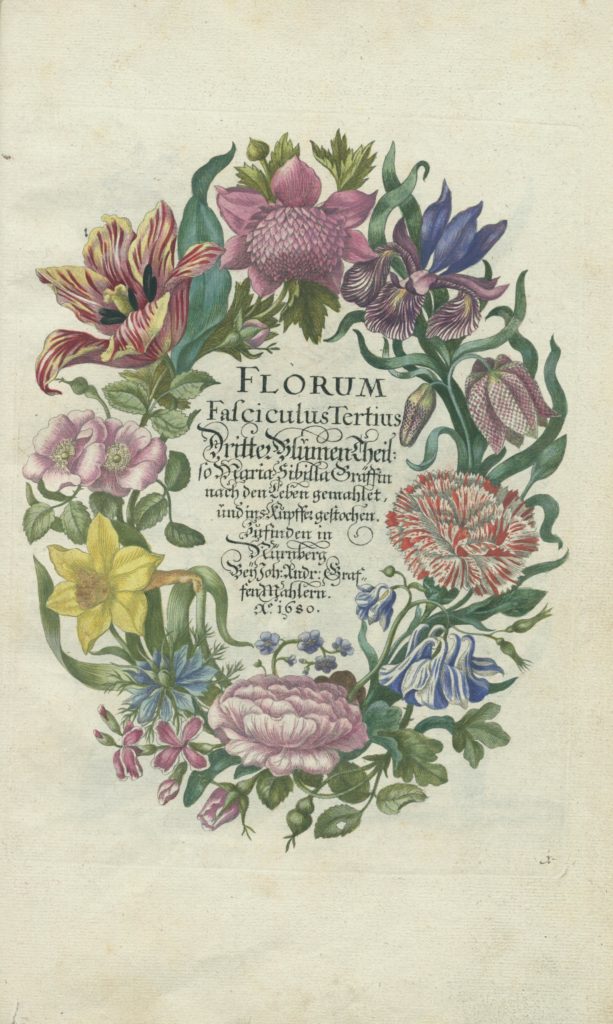

Dietzsch’s flower paintings grow directly out of this tradition. Even her use of parchment, or vellum—the preferred working surface for delicately controlled applications of gouache, or opaque watercolor—continued the techniques used by Dürer and Hoffmann, who in turn had adopted them from the earlier traditions of manuscript illumination. Dietzsch and her sister Margaretha Barbara were not the first female artists in Nuremberg to explore the world of naturalist subjects. The celebrated entomologist and naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) spent several years in the city, producing flower studies and teaching other women painters from 1670 until 1681 (fig. 5). The engraver and flower painter Amalia Pachelbel Beer (1688–1724), daughter of the famous composer Johann Pachelbel, was included in a 1730 encyclopedia of important mathematicians and artists of Nuremberg.

Women and Flower Painting in Enlightenment Europe

Dietzsch’s career as a flower painter flourished within the context of the historical development of empirical investigation, a foundation of the Enlightenment movement in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Like their counterparts in France and England, Germany’s intellectual class embraced purportedly dispassionate reason and systematic observation to de-mythologize the mysteries of nature, documenting and categorizing it on micro- and macrocosmic scale. Such goals informed the creation of visual compendia of botanical specimens as illustrations for reference texts and commissions for documentation of royal gardens.

Women artists often played an active role in these efforts. In seventeenth-century Rome, the engraver Anna Maria Vaiani’s name appears on an illustration of a vase of cut flowers in Giovanni Batista Ferrari’s De florum cultura (1633), dedicated to Cardinal Francesco Barberini (fig. 6). The Dutch Mennonite horticulturist Agnes Block engaged many artists, the still life painter Alida Withoos among them, to paint images of her garden of exotic plants at her estate Vijverhof. In eighteenth-century France, Madeleine Francoise Basseporte (1701–1780), official painter of King Louis XV’s garden, was also commissioned by Madame de Pompadour, the king’s confidante and mistress, to create visual records of the blooms in her garden, as well. Trew, the Nuremberg physician mentioned above, invited Dietzsch and her sister Margaretha to contribute their illustrations to be engraved for inclusion in his Hortus Nitidissimis (1750).

A Contemplative Approach

These intellectual pursuits offered a view of the world outside of the religious frameworks that traditionally had dominated social priorities and mindsets. But this did not mean that artistic investigations into nature during this period necessarily abandoned spiritualized interpretation. As Charlotte Brooks has pointed out, Dietzsch’s flower paintings—portraying the perfection and beauty found in nature—could have been understood as evidence of God’s role in creating them. The mesmerizing degree of detail with which Dietzsch portrayed the plants, heightened by their dramatic presentation against a dark background, encourages sustained focused viewing akin to contemporary religious meditative practices.

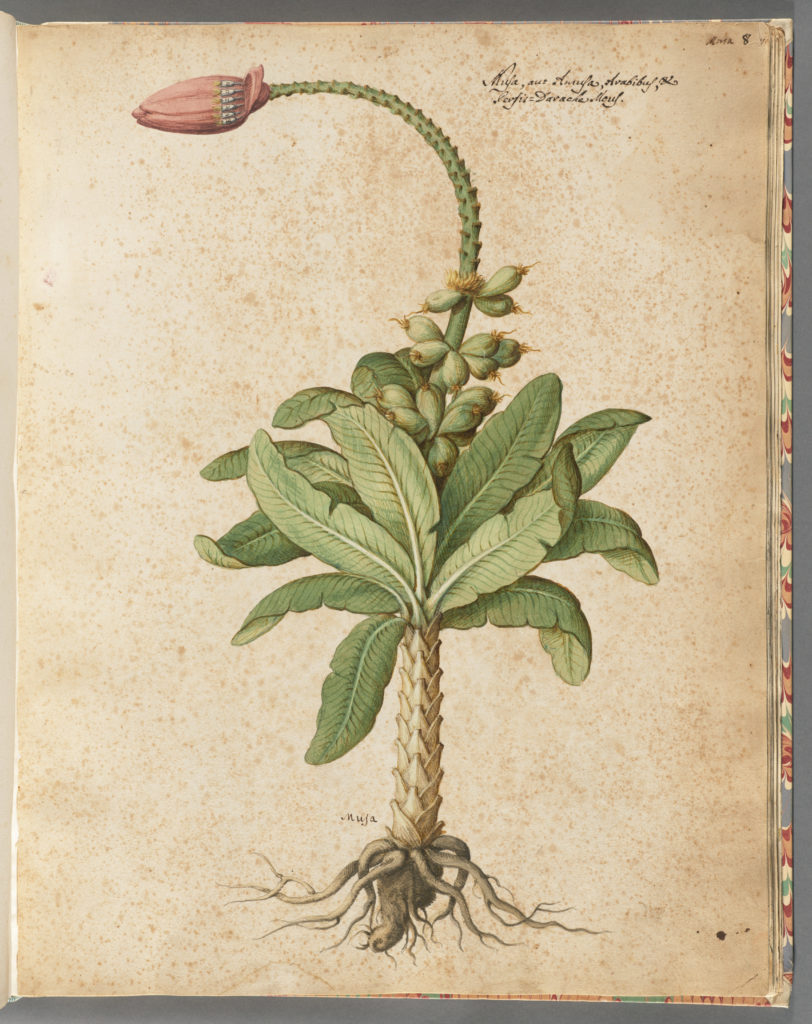

Dietzsch also distinguished her flowers from strictly scientific categorization by including insects and animal life. This further separated her art from that of the botanical illustrators, who usually focused their descriptive efforts on capturing the plant specimen in its entirety, such as the illustrations created by the Italian miniaturist and still life painter Giovanna Garzoni in her Piante varie (ca. 1631), which often included root systems, bud formations, and different states of flowering (fig. 7). In this regard, many of Dietzsch’s flower portraits, with their dark backgrounds, have more in common with artfully composed floral arrangements that appear in the still life paintings of Maria van Oosterwijck and Rachel Ruysch (figs. 8 and 9).

Dietzsch’s penchant for precise detail allies her with the scientific impulse, but the animal visitors that occupy her flowers—as in her Dandelion, Butterflies, Snail and Beetle (fig. 10)—imbue her work with a charming episodic, almost narrative quality. Her controlled but gestural application of pigment to the flower’s petals and leaves and the portrait-like presentation of the plants suggest that these works were intended as miniature paintings that would stir both mind and soul.

This hybrid appeal of Dietzsch’s flower paintings likely contributed to their broad popularity among Europe’s collecting class.

Insights on Dietzsch’s Process

In addition to Dietzsch’s obvious talent at achieving verisimilitude, she also exploited the material qualities of the media she used. Mixed to varying degrees of opacity, gouache could be layered to create exceptionally detailed visual effects that not only construct the appearance of the botanical specimen, but also imbue it with a sense of liveliness. Micro-photographs of the BMA flower paintings (taken by BMA paper conservator Linda Owen) reveal Dietzsch’s use of a gum arabic wash on select portions of the composition to produce a light reflecting effect, creating a sense of depth against the matte black background. The glossy character of gum arabic is used to brilliant effect in her selective application of it on the shiny exoskeleton of a beetle (fig. 11), or as a drop on a flower’s stamen that might recall dew or nectar (fig. 12) attracting the nearby insects.

Despite their seemingly explicit presentation, aspects of Dietzsch’s technique remain a bit of a mystery. Raking light does not reveal use of a stylus or indentation to map out the placement of compositional elements of the BMA works, and the thick parchment and remnants of linings on the drawings’ verso prevent using transmitted light to see through the paint layers.

The carbon of the black background further deters infrared reflectography to determine successfully how Dietzsch might have used underdrawing. Examination under a microscope reveals that she likely painted the whole surface of the parchment black before applying the colored pigments. Losses or dried bubbles in the media provide a view into the layers beneath, revealing a base layer of black underneath the colored pigments (fig. 13).

In examples where the pigment application on the surface is particularly light—such as in her A Branch of Gooseberries—the translucency of the plant’s forms reveal the black ground beneath (fig. 14). In addition to clarifying the detailed presentation of the subject, her use of the solid black background also had the added benefit of minimizing the deleterious effects of light on the vellum, which turns yellow with prolonged exposure.

A dark background format appears not only in flower works attributed to Dietzsch, but also in her animal studies. Two studies of dead birds placed against warmer brown backgrounds—Dead Bird Hanging (fig. 15) and A Rose-Breasted Finch Hanging from a Nail (fig. 16)—were formerly attributed to the naturalist painter Johannes van Bronckhorst (1648–1727), but are now given to Dietzsch.

The Question of Collaboration

Both Dietzsch’s flower and animal studies convey the prevalent role of repetition and reuse—a commonplace practice in artistic workshops for centuries—in the Dietzsch workshop. Several variations of similar compositions of flower and animal studies (nearly all unsigned) appear in museum collections under the names of Barbara Regina, Margaretha Barbara, and other Dietzsch family members.

While the possibility of collaboration makes it difficult to parse out individual hands, it is important to keep in mind when considering works created in a family workshop setting. Our desire to assign individual names to works of art is strong, driven by the long and robust tradition of the myth of the solitary (male) artistic genius established by Giorgio Vasari and his Lives of the Artists in the sixteenth century. But the historical reality was that most art—its materials, its formation, and its circulation—created prior to the nineteenth century was in fact the product of multiple hands, many female, whose names are now unknown to us.

Conclusion

For the BMA, the acquisition of Dietzsch’s Blue Morning Glory and Narcissus was a significant step in expanding institutional and public awareness of women artists of the early modern period and their representation in museum collections. These exquisitely rendered flower portraits provide a window not only onto the circumstances specific to Barbara Regina Dietzsch and her world, but also illustrates the broader context of artistic production during the Enlightenment period and the integral role that women played in it.

Dr. Andaleeb Badiee Banta is Senior Curator and Department Head of Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the Baltimore Museum of Art. She is a specialist in Renaissance and Baroque art of Europe, with a focus on the material aspects of old master works on paper. Earlier, Banta was Curator of European and American Art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College and Assistant Curator of Print and Drawings at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Banta has published and presented on numerous European artists of the early modern period.

Andaleeb is a co-curator of the international loan exhibition Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800. The show is on at the Baltimore Museum of Art from October 1, 2023 to January 7, 2024. It then moves to the Art Gallery of Ontario, where it opens in March 2024.

Visit Art Herstory’s Barbara Regina Dietzsch resource page.

Other Art Herstory posts to do with women natural history illustrators:

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Kay Etheridge

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

Other Art Herstory posts about eighteenth-century women artists:

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Xavier F. Salomon

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Ann Golob

Thank you for this birthday present to the rest of us. I especially enjoyed the discussion of how Dietzsch painted. We infer scientific accuracy and fall for the illusion of three dimensions right away, but those are only the most (literally) superficial evidence of virtuosity. It’s good to see that tied so explicitly to an artist’s awareness of her materials.

I also found myself wondering how somebody else altogether, Giovanna Garzoni, knew about banana plants.

Are there books or catalogues on the dietsch sisters? Their work is astonishing and this article fascinating.

Thanks for the feedback! Agreed that the work of the Dietzsch sisters is astonishing and well worthy of a book or catalogue. But unfortunately, I don’t know of any such publications.