Guest post by Paris A. Spies-Gans, Harvard Society of Fellows

In July 2020, an oil painting appeared on the art market that had long been thought lost (fig. 1). A medium-sized canvas, 111 x 145 centimeters (3.6 x 4.7 feet), it depicted a sinuous woman in white, one arm in the air, parting from a group of mournful figures in classical attire. Two pairs of women stand entwined, another figure prays, and a crowned man holds his face in his hands. Behind the bereaved group loom rocky crags and a clouded sky. This painting, portraying The Farewell of Psyche to her Family, had last appeared publicly in 1791, as part of the Louvre Salon debut of the painter Marie-Guillemine Benoist, b. Leroulx-Delaville (1768–1826). The presiding auction house in Bordeaux estimated a hammer price of 45,000 to 60,000 euros, a reasonable enough guess for a little-known woman artist whose last auctioned canvas had garnered 114,884 euros in 2004. Instead—it hammered in at 362,080 euros.

Training and Self-Fashioning

Benoist has featured in feminist art historical conversations from their inception. Her work appeared in Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris’s pioneering exhibition Women Artists: 1550–1950 (1976), and she has slowly but indelibly entered twenty-first century discourse. She was born in Paris, where her father was a royal administrator for the ancien régime state. By 1784, she and her sister Marie-Élisabeth Leroulx-Delaville, later Baroness Larrey (1770–1842), were taking art lessons from Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun; by 1786, they were studying under Jacques-Louis David. Immediately attuned to the public-facing aspects and prospects of a career in the fine arts, Benoist seems to have first exhibited in 1784. She showed a portrait of her father and two têtes d’étude at the annual one-day outdoor exhibition in Paris called the Exposition de la Jeunesse.

As she forged a professional artistic identity in pre-Revolutionary Paris, Benoist made increasingly ambitious subject choices. In a self-portrait from 1786 (fig. 2), she showed herself copying from an early version of David’s Belisarius Begging for Alms (1781).

On this canvas, which has been identified as her entry to the 1786 Exposition, Benoist presented herself clad in a loose white garment belted with a touch of red, with her shoulder exposed in a manner that would directly anticipate several of her later painted works (i.e. figs. 5, 10). The relaxed state of her dress—especially in comparison to the self-portraits that Vigée-Lebrun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard had exhibited at the Louvre Salon in 1783 and 1785 (figs. 3-4)—took advantage of the often-porous boundary between portraits of women painters and allegories of painting. (Melissa Hyde has recently illuminated several subtleties and shifts in women’s self-portraits at this time.) Even more, the canvas advertised Benoist’s distinguished artistic lineage as well as her ability to mimic her (male) teacher’s most celebrated classical works. At the 1787 Exposition, Benoist would exhibit a narrative painting for the first time: a literary scene from the English writer Samuel Richardson’s popular epistolary novel Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady (1748).

Fig. 4 (right). Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond, 1785, oil on canvas, 210.8 x 151.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 53.225.5, exhibited at the 1785 Salon.

Benoist participated so consistently at the Exposition in part because the Louvre Salon, Paris’ most prestigious venue, remained closed off to her and most of her peers—one of many, many barriers that premodern women artists faced. Only elected members of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture were allowed to exhibit, and with the double-election of Vigée-Lebrun and Labille-Guiard in 1783 the Académie had decided to enforce a quota that essentially barred further women from admission.

The Louvre Salon

Yet some changes were on the horizon. In 1791, in the spirit of the French Revolution, the Louvre Salon became open to all exhibitors, regardless of sex or Academic status. Benoist lost no time. She was one of twenty-two women who exhibited at that year’s show, and The Farewell of Psyche to her Family (fig. 1) was one of three narrative canvases that she chose to mark this debut. She was joined by her sister, who exhibited an Artemis.

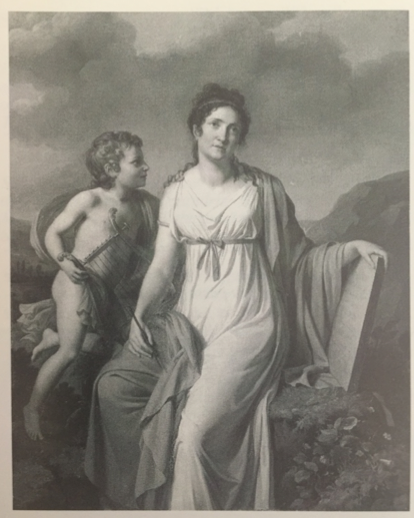

The siblings seem to have selected their subjects with care. Both submitted classical and literary works, the highest subtype on the traditional hierarchy of genres. Both also featured women within these scenes. Benoist’s other pieces were the classically-inspired Innocence between Vice and Virtue (fig. 5) and another moment from Richardson’s Clarissa. (Later, she would illustrate the French edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1797), an unfinished novel about an English woman’s unsuccessful attempts to escape inherently gendered sociopolitical structures.)

With these subject choices, it was perhaps inevitable that critical reaction would diverge. One reviewer effused, “I did not think that a woman was capable of such a historical composition, moreover with this degree of perfection.” Another, however, penned a scathing critique, excoriating women artists’ “brazen” “study of the art of painting” while paradoxically suggesting that Benoist could not have produced her works alone—that they were, rather, “made by thirty-six hands.” Variations on these two themes—moral objections to women’s rendering of the human figure and thinly-veiled suggestions that women did not author their portrait and narrative works—would continue in assessments of women’s art for decades.

Portrait de Madeleine

Still, Benoist became a Salon staple, exhibiting a combination of thirty-four narrative and portrait works through 1812. This included a now-lost depiction of Sappho in 1795 (fig. 6), the year that she acquired a coveted artist’s studio in the Louvre.

It also included her Portrait d’une négresse in 1800 (fig. 7). Lately, this work has been renamed Portrait de Madeleine in delayed recognition of research into the woman it portrays—a former slave who had become a servant in the household of Benoist’s brother-in-law. Portrait de Madeleine has been in the Louvre’s collection since 1818, when it was one of four canvases that the French state acquired from Benoist for 11,000 francs. This purchase is often described as compensation for the fact that Benoist had ended the public-facing aspects of her career four year prior. (Her husband had received a prestigious position in the Restoration government—a role that was incompatible with her further participation in public shows.)

Benoist painted Portrait de Madeleine near the end of the brief, eight-year period during which France abolished slavery in its Caribbean colonies, and scholars (including Helen Weston, James Smalls, and, most recently, Anne Lafont) have progressively underscored the racial and colonial tensions that it radiates. It should be noted that no evidence suggests that the painting represented a strong abolitionist agenda on Benoist’s part. Its renaming was sparked by Denise Murell’s powerful exhibition, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (2018–2019). Benoist’s portrait appeared under the title Portrait de Madeleine for the first time in the show’s Parisian installation.

In 2018, this painting also featured at the tail end of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s “Apeshit” music video, a commentary on the presence and absence of colored bodies in the Louvre. (Incidentally, many of the marble statues in front of which the artists posed would have originally been colored. The stark classical whiteness enshrined by the Western canon is itself a historical construction, stemming from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century “cleanings” in the name of conservation.) Portrait de Madeleine was the sole piece in the video to be featured on its own, reaffirming its fractious place in today’s canon: it has been in the Louvre’s collection for two centuries, yet its artist and subject remain outsiders.

“Successes” and Legacy

Benoist’s own outsider status is, in fact, a product of later times. Upon earning a medal at the Salon of 1804 (where she exhibited five portraits, including fig. 8), Benoist found herself with a stream of commissions from France’s new Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte.

By 1812, she had completed at least ten official portraits of the imperial family. This included images of Napoleon that were sent to towns throughout France—for which Benoist earned fees commensurate to those commanded by her male peers—as well as portraits of Napoleon’s niece Elisa Napoléone Baciocchi and the Empress Marie Louise that she exhibited at the Salon in 1810 and 1812. In 1806, when artists were forced out of their Louvre lodgings, Benoist received an annuity of 1,000 francs. These prizes, commissions, and compensational fees were markers of high status for a painter of any sex. When forced to cut short her career in 1814, she wrote a letter to her husband mourning the loss of “a life of hard work” and these meaningful “successes.”

Despite the prominence she accrued in her lifetime, Benoist has suffered the posthumous fate of innumerable women artists who have been overlooked, forgotten, and at times effaced. While her Salon and other successes ensured that several of her canvases entered the French state collection under her name, paintings without this provenance have weathered a meandering path. One of her most celebrated works, Madame Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont and Her Son, Eugène (fig. 9, likely 1802 Salon), was initially so admired because it was attributed to David from at least 1905, and it was on that basis that the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired it. Questions of authorship emerged in the 1970s, and Margaret Oppenheimer firmly reattributed the piece in 1996. Likewise, Benoist’s Portrait of a Lady in San Diego was long ascribed to David (fig. 10, likely 1799 Salon).

Fig. 10 (right). Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of a Lady, oil on canvas, 100.33 x 81.6 cm (39 ½ x 32 1/8 in.), San Diego Museum of Art, likely exhibited at the 1799 Salon.

Conclusion: Narrative Scenes Reconsidered

As Benoist’s portraits continue to be commended for their Davidian qualities and imperial sitters, the narrative paintings that she steadily exhibited also warrant renewed attention. Increasingly, Benoist selected subjects to which her audience, exhausted after years of Revolutionary violence and Napoleonic unrest, could relate.

In 1804, for instance, she showed A Young Girl Singing to Distract her Old Blind Father; in 1806, an allegorical The Sleep of Childhood and that of Old Age (fig. 11); and in 1810, an aging soldier putting his granddaughter to sleep, as his daughter reads aloud from the Bible. In 1812, for what she did not know would be her final Salon, she exhibited an elderly fortune teller (fig. 12). Throughout these works, Benoist’s highly refined attention to childhood and old age are striking, from the fortune teller’s leathery skin to Old Age’s strong, worn hands.

Benoist certainly abandoned the venerated classical genre after 1795, as scholars have noted. However, with this departure, her subject choices arguably matured, as she rendered scenes that were unattached to an entrenched canon, with its attendant and unavoidable criticisms. Having fashioned a high-profile career in the French capital across administrations and revolutions, perhaps Benoist was choosing to tell stories that she could more fully make her own—discerningly, conceptually, and, of course, creatively.

Dr. Paris A. Spies-Gans is a historian of gender and art. She received her PhD in History from Princeton University and her MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art. She is currently a Junior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Follow her on Twitter at @ParisSpiesGans.

By the same author:

Exhibiting Women: The Art of Professionalism in London and Paris, 1760–1830, by Paris Spies-Gans

Other Art Herstory posts to do with French women artists:

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Dr. Jessica L. Fripp

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Dr. Kelsey Brosnan

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by novelist Drēma Drudge

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Dr. Georgianna Ziegler

Other Art Herstory posts to do with 18th-century women artists:

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Dr. Christina K. Lindeman

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Dr. Anita V. Sganzerla

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Dr. Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Dr. Ann Golob