Guest post by Paris Spies-Gans, Harvard Society of Fellows

Although rarely acknowledged or discussed in these terms, the period from 1760 to 1830 was a watershed moment for women artists in Britain and France. In fact, it was in both nations in these exact years that women began exhibiting their art in truly unprecedented numbers. Through this public activity, they forged lucrative careers as painters, sculptors, engravers, and more.

The evidence of their artistry survives in abundance: in personal journals, letters, exhibition reviews, financial accounts, state papers, reproductive prints, and works of art held in museum and private collections globally. When brought together, these traces of hard-won accomplishments and employment disprove several assumptions about women’s artistic production before the late nineteenth century.

It is far past time for these women’s stories to be integrated into our understanding of the intricate, deeply influential art worlds of Revolutionary-era Britain and France.

Delayed Recognition

Recently—and for the first time in nearly two centuries—women artists from this very period have begun to receive a noteworthy amount of public, popular attention. In early 2019, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s (1755–1842) Portrait of Muhammad Dervish Khan (Fig. 1) set a record when it sold for nearly $7.2 million at Sotheby’s, the highest price accrued at auction by a woman artist from pre-modern times. Later that year, French director Céline Sciamma released her ethereal Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (Portrait of a Lady on Fire), a film about a young eighteenth-century female artist whose story was based in part on Vigée Le Brun’s own autobiographical Souvenirs (1835–37).

Museums quickly followed suit. In 2020, the Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf hosted a major show on Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807; Fig. 2), the only artist from the time who arguably rivals Vigée Le Brun in twenty-first-century fame. (Unfortunately, the Royal Academy, London’s installment of this show was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.) In 2021, Paris’s Musée du Luxembourg placed dozens of these artists’ peers on group display for the first time in France with Peintres femmes, 1780–1830: Naissance d’un combat (Women Painters, 1780–1830: The birth of a battle).

In March 2022, San Francisco’s Legion of Honor museum announced the acquisition of Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s (1768–1826) recently rediscovered Psyche Bidding Her Family Farewell (Fig. 3); Benoist was a student of Vigée Le Brun and Jacques-Louis David. A massive classical canvas by another David pupil, Sophie Frémiet Rude (1799–1867), sold for another record sum ($685,500), again at Sotheby’s, earlier in the year.

Vigée Le Brun, Kauffman, Benoist, and Rude have been hailed as atypical successes or exceptions. But they were far, far from alone.

Professional Status

From 1760 to 1830, as the American and then French Revolutions shook each nation to its core, the primary path to professionalization for artists of both sexes was to exhibit in one of Britain’s and France’s most prestigious, vetted exhibitions: London’s Royal Academy of Arts and Paris’s Louvre Salon (Figs. 4 and 5).

At these two venues, more than one thousand women exhibited more than six thousand works of art, spanning nearly every medium and genre (apart from architectural designs). Each of these pieces was accepted for display by an all-male jury—the same committee that selected works by male exhibitors. Yet despite women’s ubiquitous, growing presence at both forums, it has largely been believed that very few women had the ability to become artists during these historically momentous decades. When women’s presence in public shows has been acknowledged, it has generally been assumed that they were “amateur” artists who, in London, were explicitly labeled as “Honorary” participants in exhibition catalogues.

However, the majority of these exhibitors were not amateur practitioners, nor were they identified as “Honorary.” Rather, they listed their names and addresses in exhibition catalogues, signaling professional intent by inviting potential clients to visit their studios to view, buy, or commission additional works of art. These painters, sculptors, and engravers’ activity defies common conceptions about women artists in the pre-modern era.

Artistic Training: Commercial Households

How were so many women able to become artists, especially while being—famously—excluded from their nations’ premier, Academy-based schools of artistic training?

In Britain, like their male peers, female exhibitors most often grew up in artistic households, spaces that were much more commercially- and professionally-focused than scholarship has recognized. For instance, in the late eighteenth century, the painter and printmaker Jonathan Spilsbury imparted lessons to his daughter Maria Spilsbury, later Taylor (1777–1820), that he hoped would be both visual and profitable.

From 1789 to 1791, the Spilsbury family lived in Ireland. While there, a childhood friend later recalled, Jonathan taught his daughter from a book of skeletons and pieces from antique statues. Apparently focused on helping her gain a command of anatomy, Jonathan “made [Maria] draw outlines rapidly of all that had any grace or beauty allowing her to shade them only slightly and she acquired early such a facility in sketching graceful figures, that a few years afterwards it became as easy to her to sketch from her imagination as to most people to write.” These lessons had a commercial bent—as the friend added, Jonathan “wish[ed] to make [Maria] earn her bread, if necessary, in later life as an artist.” (The contents of this letter appear in the book Reminiscences of Marianne-Caroline Hamilton (1777–1861)).The family returned to London in 1791, and Maria Spilsbury debuted at the Academy the following year. She exhibited at both the Academy and the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom for the next two decades, before moving back to Ireland (Fig. 6).

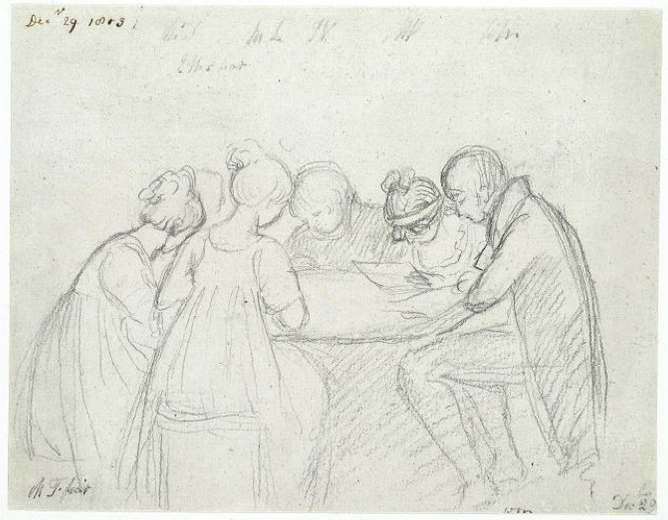

Other women adjusted the courses of their careers in the wake of mid-life developments. Elizabeth Mulready, b. Varley (1784–1864), began exhibiting at the Academy in 1811, two years after separating from the artist William Mulready. Presumably, she sought a way to support herself and their three sons, who also became artists. Nearly a decade earlier, she had featured in a delicate sketch by the exhibiting painter Mary Ann Flaxman (1768–1833, Academy debut 1786) (Fig. 7). With pencil and paper, Flaxman loosely pictured a gathering of male and female family members and friends around a drawing table, all engrossed in their sketching—likely, per a range of different familial accounts, a frequent activity in the homes of British artists.

Artistic Training: Male Artists’ Studios

Across the Channel, by contrast, women dominantly pursued professional goals by studying with a male artist who was not a family member: more than one hundred male artists taught more than 180 women who exhibited their art in Paris. Jacques-Louis David himself trained more than twenty women, fifteen of whom exhibited publicly, fourteen at the Louvre; Jean-Baptiste Regnault instructed at least thirty-four exhibiting women artists.

Among David’s pupils, Angélique Mongez, b. Levol (1775–1855) emulated her teacher’s style most thoroughly, exhibiting nine hefty classical history canvases alongside other works at the Salon from 1802 through 1827 (Fig. 8). In 1813, in a letter to the director of the Musée de Lyon, David praised a copy that Mongez made of his portrait of Napoleon, writing that “she surpassed my hopes as, instead of a servile copy, she produced a genuine original…this painting can only add to her reputation.” (David to M. Artaud, April 4, 1813; my translation from the French original as presented in Documents complémentaires au catalogue de l’oeuvre de Louis David.)

David developed a close friendship with both Mongez and her husband, a relationship that they sustained after he moved to Brussels, in self-imposed exile following the Bourbon Restoration of 1815. Mongez continued to paint in Paris while engaging with David’s art from afar; in one letter from May 1824, she praised David’s latest painting, recently sent to the French capital. Antoine added a postscript: “I cannot add anything to the testimonies of admiration expressed in my wife’s letter. I feel them, but I will not express them as well, as I am just a poor ‘amateur.’” Playfully but clearly, Antoine corroborated his wife’s higher standing as an artist, in contrast to his own “amateur” interest.

Studying in Public Spaces

As the nineteenth century progressed, aspiring artists in both nations also began to take advantage of new opportunities to study from works in public spaces. In London, this included the galleries of the British Institution and the British Museum’s Townley Gallery of classical sculpture, the latter recently and wonderfully documented by Martin Myrone.

Sometimes, women ventured to these galleries (Fig. 9) as part of family groups. In 1817—the year she debuted as a portrait painter at the Academy—Janet Ross, later Barrow (1795–1861), registered to study at the Townley Gallery alongside her brother and sister. Her brother, also a portraitist, had first exhibited at the Academy the prior year. Across the Channel, women similarly studied the paintings and sculptures in the Louvre’s public galleries, as documented most famously by Hubert Robert and described in lesser-known letters by the Swiss portraitist Amélie Munier-Romilly (1788–1875).

Subject Choices in France: Historical Works

Such educational opportunities profoundly informed artists’ genre choices. As Angélique Mongez’s own selections suggest, when creating art for submission to public shows, she and her peers commonly gravitated towards subjects that were both commercial and prestigious: narrative scenes and portraits in France, and narrative scenes, portraits, and landscapes in Britain. Again and again, they found themselves rewarded for these decisions with their works’ acceptance and public display.

A number of these paintings survive, including the English Elizabeth Harvey’s (1778–1858) Malvina Lamenting the Death of Oscar; her companion trying to console her, which hung at the 1806 Salon (Fig. 10). This was Harvey’s third year exhibiting in Paris, and her first narrative to grace the Louvre’s walls. Taking its subject from Ossian—a purportedly epic poet who was actually the creation of the eighteenth-century Scottish writer James Macpherson—Harvey’s canvas shows the smoothness and depth that may have soon led her to receive a second-class medal at the Salon of 1812. Throughout her years exhibiting, Harvey (who would later become the Comtesse de Pully) lived in the French capital with her mother and half-sister, where they knew the likes of François Gérard, Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who once made a drawing of the two sisters in a close embrace (Fig. 11).

Malvina Lamenting the Death of Oscar provides scarce clues to Harvey’s once-recognized practice and skill. Strikingly, she has used a moment of mourning to stress a dually emotional and compositional interplay among women. Malvina appears sitting, the sole figure clad in white, head bent in profile; her billowing scarf echoes the curves of her companions’ harp, lyre, and bow, as well as the murky sky, clouded over to mirror her gloom. All of the women seem to radiate light from within.

Subject Choices in Britain: Portraiture

While British women, too, exhibited narrative works throughout the period—most famously Angelia Kauffman (Fig. 12), but also Mary Moser, later Lloyd (1744–1819), Maria Cosway, b. Hadfield (1760–1838), Maria Spilsbury, and Mary Anne Ansley, b. Gandon (fl. 1812–, d. 1840), among others—portraiture quickly became the principal subject choice for all artists exhibiting at the Academy.

This owed to British artists’ own sense of their visual strengths, as well as a stream of new commercial opportunities following the onset of the American and then the French Revolutionary Wars. Kauffman, Cosway, Anne Forbes (1745–1834), Mary Ann Flaxman, and Eliza Trotter (fl. 1800–1814) number among those who exhibited oil portraits that survive (Fig. 13). The Drummond, Byrne, and Sharpe sisters became widely hailed experts in miniature.

A few others even portrayed their contemporaries in marble and wax. Women sculptors were rare, and faced even higher barriers to success than women who pursued careers as painters. Still, at least one contemporary writer recognized the medium’s potential for members of her sex. In 1798, the Quaker author Priscilla Wakefield reflected that “the productions of the honourable Mrs. [Anne Seymour] Damer [b. Conway (1748/49–1828)], and a few others, authorize as assurance, that women have only to apply their talents to [statuary and modeling] in order to excel.” (Fig. 14)

Margaret Carpenter

By the end of the period, Margaret Sarah Carpenter, b. Geddes (1793–1872), was on her way to becoming one of the leading portraitists of Victorian Britain. She exhibited regularly at the Academy from the age of twenty-one, showing more than 150 works from 1814 through 1866. (For a brief overview of her career, see the Oxford DNB entry by Richard J. Smith.) Her surviving pieces, mainly oil paintings, demonstrate consummate confidence and skill (Fig. 15). Her portraits won no shortage of acclaim, as well as critical assertions that she would have won several Academic prizes…if she had been a man.

In 1839, a reviewer for the Art Union even wrote that, given Carpenter’s talent as a portraitist and the high quality of women’s exhibited works overall, the Academy should elect her to its ranks. In addition to rewarding Carpenter’s own skill, this could set an example that others of her sex could follow:

Now that women are maintaining their intellectual rank, and affording daily proofs that the ‘soul is of no sex’, the Academy might give a fine example to the nation and to the world – by distinguishing such a painter as Mrs. Carpenter…from among the thousand competitors for fame.

Carpenter also was one of numerous men and women who solidified audiences for ever-more elaborate prints after their painted, drawn, and sculpted works (Figs. 16–17).

Conclusion

Margaret Carpenter’s story has not been lost, nor have those of Spilsbury, Mongez, Harvey, and their many, many peers. They have been written out of art historical narratives—yet, remarkably, remain largely recoverable. It is my hope that the current resurgence of interest in female artists across institutions and media will lay new roots for incorporating these women’s accomplishments, defeats, and experiences into our ever-evolving understanding of the past—not as rarities, but as the influential players that, it seems, they always were.

Dr. Paris A. Spies-Gans holds an MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art and a PhD in History from Princeton University. Her research concentrates on the history of women, gender, and the politics of artistic expression. Her book A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 is newly published by the Paul Mellon Centre / Yale University Press. Her second book, A New Story of Art—a narrative history of Western art, integrating the central roles women artists have regularly played—is forthcoming from Doubleday. Follow her on Twitter at @ParisSpiesGans.

Other Art Herstory posts to do with French women artists:

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

Other Art Herstory posts to do with British women artists:

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

Other Art Herstory posts to do with 18th-century women artists:

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, Guest post by Ann Golob

Trackbacks/Pingbacks