Guest post by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, Georgetown University (emerita)

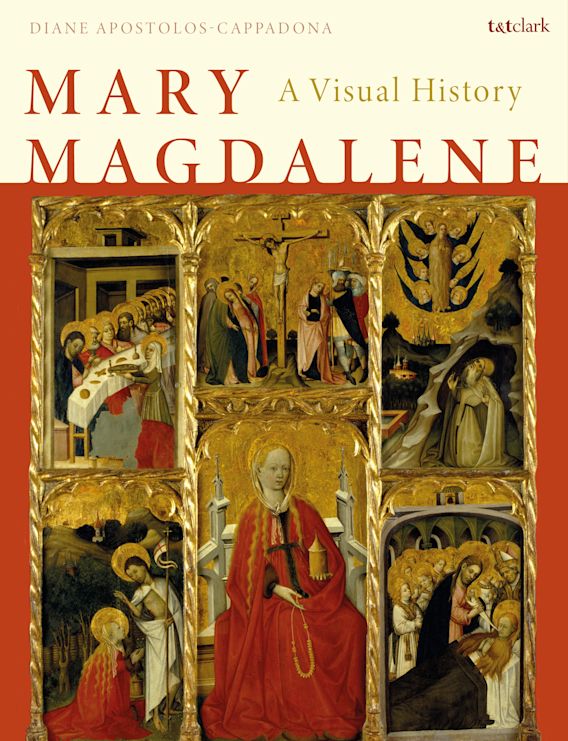

Starting with the recognition that both artist and viewer shape, in cultural and religious terms, how Mary Magdalene has been perceived, identified, and categorized across time, my new book Mary Magdalene: A Visual History explores artistic depictions of the saint from premodern times to the present.

Mary Magdalene: A Visual History includes illustrations of works by women—premodern and contemporary—as well as by men. But as I note in the introduction, “For every image and symbolic motif of the Magdalene that I can write about there are not simply hundreds but probably thousands of others.” It is also the case that since the publication of Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay “Why have there been no great women artists?” more and more research and curatorial interest has uncovered a wealth of previously missing or “anonymous” women painters and sculptors. Specialists are rediscovering works by these artists at a prodigious rate.

Therefore, I am pleased to present—and illustrate—some further reflections here about depictions of Mary Magdalene by early modern women artists whose works are still available to us today.

Pre-Tridentine Mary Magdalene

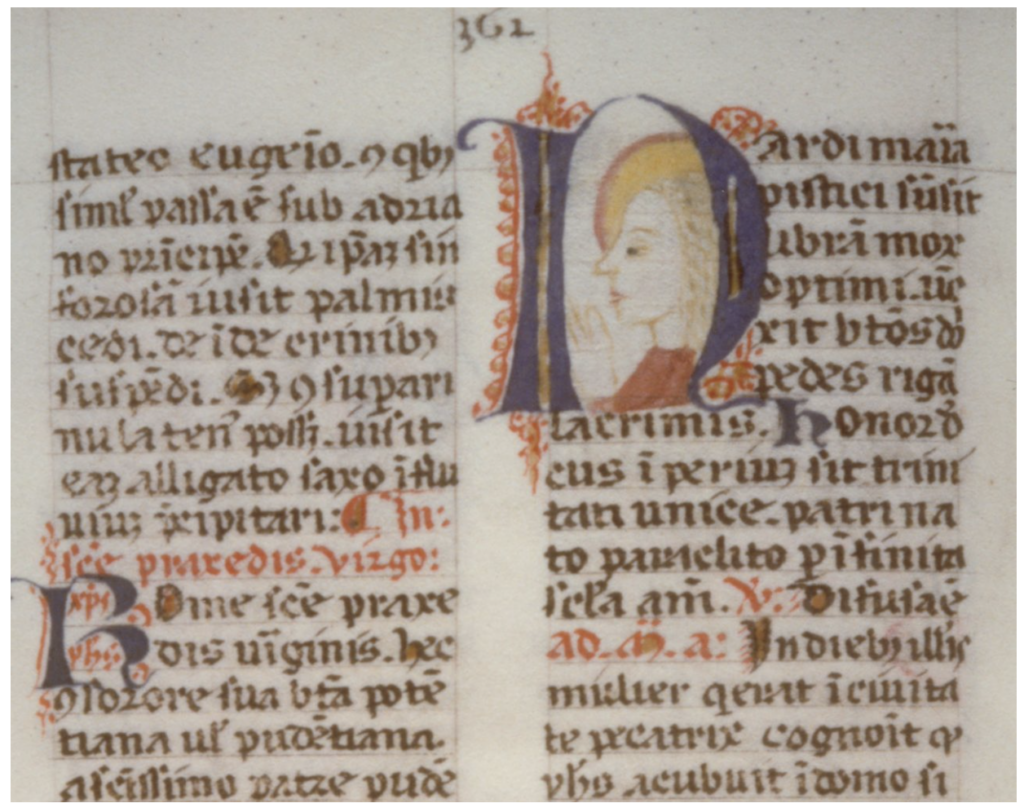

Among the earliest identified women artists—known to us by name, historical data, and distinguishable artworks—to transform the image of Mary Magdalene were nuns. One of the first autograph artists to transform the image of Mary Magdalene was Sister Caterina Vigri (1413–1463), later Saint Catherine of Bologna.

A member of the Franciscan Convent of Corpus Domini in Bologna, Vigri participated in the reform movement Observance (observantia/observantia regulae). The movement promoted pastoral and spiritual ardor, so her minimalist image of the Magdalene (figure 1) supported the prayer life of her religious sisters.

Mary Magdalene in early modernity

As art, theology, and society moved from the High Renaissance into the milieu of the early modern, more women artists were recognized as individuals independent from their convents, or from their artist fathers, from whom they garnered their earliest training in painting, sculpture, and prints and engravings. These women created art after the Council of Trent, which met in three sessions between 1545 and 1563 as a critical element in Roman Catholic Church’s formal response to the questions and concerns of the Reformers. At the 25th and final conciliar session in December 1563, the last document issued by the council was concerned with the role of saints, relics, and art.

This document and its interpretation informed the approach of many women artists in the Roman Catholic world, including in Italy, Portugal, and Spain. As they emphasized the moral and religious effectivity of biblical women, and female heroes and saints, these artists singled out the Magdalene as a model of spiritual action and values.

Mary Magdalene as portrayed by Italian women

Almost a century after Caterina Vigri, Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588), a member and later prioress of the Dominican Convent of Santa Caterina da Siena in Florence, established a workshop both for her own painting and for the training and promotion of artist-nuns in other Dominican convents in Tuscany which became a model commercial enterprise. She included an innovative posturing for the Magdalene in her Lamentation with Saints (c.1550s; figure 2) for the refectory of her own convent.

Among the better-known early modern women artists whose work includes depictions of Mary Magdalene are Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614), Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–after 1654; figure 3 illustrates one of her many paintings of the saint), Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665, who also painted several variations on this theme), and Fede Galizia (1578–1630), whose most significant commission was a Noli Me Tangere for the high altar of the Church of Maria Maddalena in Milan (figure 4).

Orsola Maddalena Caccia

Lesser known until recently was the Ursuline nun and abbess Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596-1676), whose carefully detailed depictions of established biblical and theological motifs provided new symbolic insights. Although she led a cloistered life in a convent in Moncalvo, Caccia earned critical acclaim in Piedmont. She incorporated aspects from Flemish paintings and engravings, especially still life elements and Lombard landscapes that linked the sacred with the secular. Such fusion is evident in her two paintings of Mary Magdalene (c.1620s; figure 5) and The Penitent Mary Magdalene [in the Wilderness] (c.1625; figure 6).

Caccia’s Mary Magdalene

In this work, the elegantly dressed and richly bejeweled saint is seated as the upward gaze of her tilted head, resting on her right hand, promotes her meditation in preparation for her conversion. Her traditional attributes, including an ointment/unguent jar, skull, open Bible, flail, and/or crucifix, are absent.

However, the floral symbols—thornless white roses in her left hand and the red rose on the windowsill but diagonal to her tilted head—signify her potential salvation. Thornless roses were a symbol of Eden before the Fall, while the yellow jonquil indicates the Easter season, and the blue columbine signifies the Holy Spirit. The inclusion of these flowers in the painting affirms the sacrality of penitence and conversion.

Caccia’s The Penitent Mary Magdalene [in the Wilderness]

Caccia’s The Penitent Mary Magdalene presents a poorly dressed and emaciated Magdalene in a landscape. The setting is rich with complex symbolism denoting the meaning of Christ’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection, to which the saint stood as witness. Emphasizing the devotional significance of meditation by her position in the left corner of the canvas, she kneels outside of her cave at La-Saint-Baume. There is a crucifix above her head and her flail is below her bent right leg as a vision filled with animal symbols relating to Christian salvation opens before her. Her right hand reaches toward the Christ Child, who caresses a deer as other animals—including a lion, rabbits, and birds—and floral symbols allude to the narrative of redemption.

Mary Magdalene as portrayed by Iberian women

The complex history of the Roman Catholic Church in Portugal and Spain, especially in coordination with the monarchy, is highlighted by their conflicting interests in dominating women’s, especially religious, roles in public and the reality of those women religious who became active spiritual leaders, authors, and patrons. Among the most notable was Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) who promoted Mary Magdalene as a model for women’s role as preachers and female piety both inside and outside convent walls. Religious orders and wealthy patrons commissioned altarpieces for churches and convents, and paintings for personal devotion, featuring the Catholic iconography promoted by the Council of Trent (1545–1563). This development presented new venues for the work of women artists.

Josefa de Óbidos

Educated by Augustinian nuns and influenced by the Jesuit and Carmelite orders in Portugal, Josefa de Óbidos (born Josefa de Ayala Figuera; 1630–1684) appears never to have formally taken religious vows. That said, she apparently lived at the Convent of Santa Ana in Coimbra from 1644 to 1646, which afforded her the opportunity to perfect both her art and her Catholic faith without any pressure to marry. Although trained by her artist father, she fashioned a unique lifestyle as a woman artist who oversaw her own studio, garnered significant public and private commissions, and signed many of her artworks, so that her name was recognized in her own lifetime and not forgotten to history. At the age of 29 and having received parental consent, Óbidos applied successfully to become Donzela emancipada, an emancipated woman, unmarried and financially independent from her family.

Her earliest paintings were on copper. Since the medium was typically small, it allowed for intricate detail with a smooth surface, was marketable, and allowed the artist, ostensibly female, to work from home. The size of the copper panels could be inset on the private oratories located either in conventual cells or small chapels. Further, nuns were responsible for the smaller chapel altars and those placed throughout the cloister. Renowned for devotional narrative and still life paintings, Óbidos portrayed women as female heroes, manifesting her own dedicated faith and daily life of religious piety. This portrayal is reflected in her most well-known paintings of Mary Magdalene, including her first mature work, Saint Mary Magdalene (c.1650; figure 7).

Josefa de Óbidos’ Saint Mary Magdalene

This delicate painting, while intimate in scale, offers a visual encounter with the sinner-turned-saint as she stands in the dramatic interior chamber setting bathed in the glow of the candlelight highlighting her face, hands, and upper torso in chiaroscuro typical of Baroque art.

Although promoting the Magdalene’s repentance as her elegant garment begins to fall from her shoulders, revealing her white underdress, simplistic coiffure, and the absence of jewelry, Óbidos envisions a singularly spiritual experience. The saint’s gestures invite the participation of the viewer, and accent the presence of her traditional attributes of silver ointment jar, scourge, Bible resting on a skull, and a crucifix. The visual synthesis of the elegant fabrics and soft sensuous flesh of the Magdalene’s upper torso contrast with the internal sorrow etched on her face, projecting the complexity of this saint’s hagiography.

Josefa de Óbidos’ The Penitent Magdalene Comforted by Angels

Óbidos’ later painting The Penitent Magdalene Comforted by Angels (1679; figure 8) is set within an identifiable theatrical Baroque composition found in other artists’ presentations of saintly encounters of spiritual ecstasy or death. The luminous colors, especially the Magdalene’s pink satin garment, the angels’ ebullient wings and floating sashes, and swirling clouds envelope the upper portion of the painting toward both the prone body of the Magdalene, crowned with a wreath of flowers above which rests her halo. She is surrounded by her attributes of the scourge, skull, crucifix, and ointment jar.

Again, the dramatic lighting of the scene emanating from the upper left corner highlights the music-making angels and the Magdalene, as does the central candle that rests between the thumb and index finger of the Magdalene’s right hand. The candle is further supported upright in the right hand of the angel garbed in a red dress with blue underdress and a teal girdle that swirls out between his wings. Another angel in the right foreground gently supports the Magdalene’s left hand as it rests above the skull, and near her ointment jar. Small in size and intimate in scale, Óbidos’ copper panel extends beyond its physical borders in terms of visual impact of mystical ecstasy and artistic piety.

Sor Joana Baptista

There is little to no documentation, biographical and otherwise, for Sor Joana Baptista (mid to late seventeenth century) except the confirmation that this nun had no art training and belonged to the Maltesas Convent of S. João of Estremoz. Her paintings, meant—like those painted by Caterina Vigri and other nuns—to be seen and to inspire other nuns, promoted the Magdalene as a female exemplar of positive Christian behavior and pious devotion. For example, her small copper painting of Saint Mary Magdalene renouncing worldly vanities (late seventeenth century; figure 9) is a visual transformation of the traditional toilette scene of an elegant lady preparing either for the beginning or the end of her day.

The stylishly appointed room in which the Magdalene stands as she removes her jewelry accentuates her renouncing the world as she begins her life of penance in the desert or wilderness cave. As the viewer’s eyes move across the copper place in a horizontal manner from left to right there is a painterly pattern to the Magdalene’s journey from a life of earthly pleasures signified by her lute, casket, and richly appointed furnishings past her composed, if not meditative, posture toward the “cast off” riches toward her unguent jar and a vase. The vase is filled with roses and lilies indicative of Christian salvation, echoing further the paradise garden viewed through her window.

Mary Magdalene in England: A work by Mary Beale

The daughter of an English clergyman, Mary Beale (1633–1699) is best known for her portraits, especially of those within her intellectual circle during the 1670s. A professional painter from the mid-1650s, her The Penitent Magdalene (c. 1672; figure 10) depicts what might best be identified as a devout Anglican perception of the Magdalene as the female embodiment of penance.

The auburn tint to her hair and the upward gaze of her titled head references the red-headed medieval Magdalene. The otherwise simple drapery of her lavender garment is highlighted by the white accents of her undergarment at the neckline and sleeves and not by encrusted jewels or heavily detailed embroidery. Her two hands—her right-hand palm-side up languidly resting in her lap and her slightly diagonal elevated open but palm-side down left hand—visually mimic the gestures common in medieval and Renaissance paintings of the Noli Me Tangere. The viewer’s eye is pulled to the white ointment jar at her left elbow.

Conclusion

Even now, between my book Mary Magdalene: A Visual History and this blog post I have not exhaustively covered the known images of Saint Mary Magdalene by early modern women artists. In the book’s notes, I mention several artists whose work is known to include at least one depiction of the Magdalene: Diana Scultori (1547–1612), Anna Maria Vaiani (fl. 1627–55), Maria Felice Tibaldi Sulbyeras (1707–90), and Luisa Roldán (1652–1706). And there are also portrayals by Eufrasia Burlamacchi (1482–1548), Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670), Maria dos Anjos (1631–1677), Élisabeth Sophie Chéron (1648–1711), Teresa del Pò (1649–1716), and Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757). Given the extent to which the Magdalene has inspired artists throughout time, it is exciting to contemplate that there are more paintings, prints, and sculptures of this saint created by female painters, sculptors and printmakers, still waiting to be rediscovered.

Diane Apostolos-Cappadona is Professor Emerita of Religious Art and Cultural History, Catholic Studies Program, Georgetown University. Her latest book is Mary Magdalene: A Visual History (2023). Her other books include A Guide to Christian Art (2020), and Biblical Women and the Arts (2018), including her “The Female Breast Sacred and Profane: Mary & Eve.” Online publications include “Visions of Mary Magdalene,” Minerva Magazine; “Iconography Overview: Noli Me Tangere” for Touch Me Not, Center for Religion and the Human, Indiana University; “’…into the hand of a woman…’: Biblical Modes of Female Agency,” Visual Commentary on Scripture; and “Judith (in Art),” SBL Bible Odyssey. Research interests include iconology of women in religious art, and Christian iconography.

More Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Plautilla Nelli and the Workshop of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio, by Alessia Motti

Luisa Roldán: Escultora Real Review, by Olivia Turner

Female Solidarity in Paintings of Judith and her Maidservant by Italian Women Artists, by Sivan Maoz

Plautilla Nelli and the Restoration of her Altarpiece Madonna del Rosario. by Jane Adams

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Kathleen G. Arthur

Sister Eufrasia Burlamacchi (Lucca, 1478–1548), by Loretta Vandi

Suor Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Angela Ghirardi

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Helen Draper

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Xavier F. Salomon

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Elizabeth Lev

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Judith W. Mann

Finding Luisa Roldán: A North American road trip, by Cathy Hall-van den Elsen