Guest post by Jacqueline Thalmann, Christ Church, Oxford

I recently wrote an Art Herstory guest post about two drawings by Elisabetta Sirani—a Self-Portrait and a Head of a Madonna. This took me back to the fascinating subject of self-portraiture, particularly female self-portraiture during the Renaissance and Baroque.

I am by no means alone in my interest, as a substantial amount of literature on the subject testifies: Joanna Woods-Marsden’s book on Renaissance Self-Portraiture (Yale University Press 1998), for example. Specific to Bolognese artists is Babette Bohn’s 2004 Renaissance Studies article Female self-portraiture in early modern Bologna. And more recently there was Letizia Treves’ ground-breaking exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi at the National Gallery in London. Artemisia’s self-portraiture ran as a major thread through the exhibition and its catalogue.

An artist’s own body is a perfect model and tool—be it the extremes to which Marina Abramović pushes herself, or what seems a simple sketch on paper by a female artist of the seventeenth century. Interesting discussions can be had in comparing Abramović with the torture Artemisia endured during her rape trial, an experience that may or may not have found its outlet in what has now become her signature painting—Judith Beheading Holofernes.

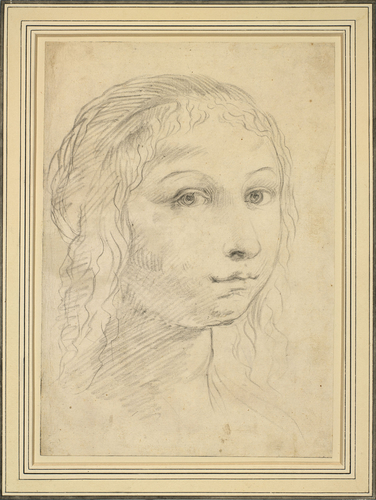

Returning to Elisabetta Sirani, there are now at least three drawn heads thought to be self-portraits: in Christ Church, in the Royal Collection, and at Smith College (a recent acquisition). A fourth drawing, fairly undistinguished and unattributed, also in the Royal Collection, seems to related to this group, too.

By looking at these four drawings, we enter the challenging realm of comparing likenesses. They are of the same period, geographical area and broadly in the same technique. If one agrees that they show the same person, the differences, like the slightly receding chin and higher set eye brows in the Windsor self-portrait, can be explained by the different ages of the artist. The subject’s changing gazes in the portraits—from surprised rebelliousness, via huffy assuredness to a calm, self-possessed confidence—might also lead one to see personal development in the sitter.

One is tempted to suggest a chronology of: The Royal Collection in Windsor (at age 15/16), Smith College (at around 20) and Christ Church (at 25/26). Do we see that in the drawings and their styles, or is it what we want to see?

And what do we make of the weaker anonymous Bolognese drawing? Is it a self-portrait of one of Elisabetta’s less talented sisters? Or a copy of one of her self-portraits, by another, less accomplished artist? What else can we see and learn about Elisabetta when we also look at her painted self-portraits?

Or what of her enduring fame when we also include copies after them, like the one by the eighteenth-century artist Giuseppe MacPherson?

Bringing some of these images together here might help us to think about them and to find some answers to these questions.

Jacqueline Thalmann is Curator at Christ Church Picture Gallery in Oxford, where she is in charge of the collection of Old Master paintings, drawings and prints. Her interests are broad and far-reaching and are trying to connect what apparently seems disparate. Follow her on Twitter.

More Art Herstory guest posts about Bolognese women artists:

Elisabetta Sirani’s Studio Visits as Self-Preservation: Protecting an Artistic Career, by Victor Sande-Aneiros

Stitching for Virtue: Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, and Textiles in Early Modern Bologna, by Dr. Patricia Rocco

Drawings by Bolognese Women Artists at Christ Church, Oxford, by Jacqueline Thalmann

Celebrating Bologna’s Women Artists, by Dr. Babette Bohn

Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani at the Smith College Art Museum, by Dr. Danielle Carrabino

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Dr. Adelina Modesti

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Dr. Elizabeth Lev

Sister Caterina Vigri (St. Catherine of Bologna) and “Drawing for Devotion,” by Dr. Kathleen G. Arthur

More Art Herstory guest posts about Italian women artists:

Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters, by Dr. Jesse Locker

“La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni (Guest post/review by Dr. Sara Matthews-Grieco)

Plautilla Bricci (1616–1705): A Talented Woman Architect in Baroque Rome, by Dr. Consuelo Lollobrigida

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves, by Dr. Katherine McIver

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), Convent Artist, by Dr. Angela Ghirardi

Two of a Kind: Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, by Dr. Mary D. Garrard

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective, by Dr. Judith W. Mann

What! You mean woman and selfies aren’t new after all! I love it!