Guest post by Nicole E. Cook, Project Coordinator for Academic Partnerships, Philadelphia Museum of Art

with the arms of the Ter Borch family, 1659,

with a poem by J.H. Roldanus. Source: Rijksmuseum

Getting Back into History

Part of the work of recovering the histories of early modern creative women is learning to look beyond the original confines of the early modern art guilds and art market. As other contributors to the ArtHerstory blog page have commented, the early modern art market was almost entirely controlled by men and frequently barred women from joining entirely. The few exceptional women, such as Judith Leyster, who were able to join a guild and set up shop professionally, faced significant challenges. In Leyster’s case, she ultimately largely withdrew from the market all together and yet new research by Frima Fox Hofrichter and others has revealed that she unquestionably continued to paint and maintain her artistic identity.

In this post, I consider another female artist from just a generation after Leyster, Gesina ter Borch. Ter Borch is often defined as an “amateur” artist. Despite being born in 1631 to a highly artistic family, she never apprenticed professionally, never joined a guild, never showed her works publicly, and, as far as we know, never sold a work of art. And yet she created hundreds of finely-painted, immediately captivating drawings and paintings over the course of her lifetime. Gesina ter Borch was an artist and she thought of herself as an artist, as her multiple self-portraits and allegorical imagery attest.

Thinking of Gesina ter Borch as an “amateur” brings up two issues. First, how, as Elizabeth Honig has eloquently discussed, the tendency to align women with amateurism is overtly gendered. Second, it is necessary for art historians to expand our understanding of women’s creative practices by looking at what women actually created, not what they sold. Market-based approaches to art history are simply not enough when it comes to the more complex ecosystem of early modern creative women.

Eclipsed by her more famous older brother, professional painter Gerard ter Borch II, Gesina ter Borch’s artwork never received interest outside of her immediate social circle during her lifetime or in the centuries following. This changed only in 1882 when art historian Abraham Bredius rediscovered the family’s albums that Gesina herself had carefully compiled and preserved. The Rijksmuseum acquired the albums of drawings. But after the initial flurry of attention, interest in Gesina’s work was largely subjugated to what her albums could tell art historians about her more famous older brother. It took another hundred years before Gesina ter Borch, thanks to the work of Alison Kettering and Hans Luijten*, received serious scholarly recognition and public interest.

Elizabeth Honig’s article “The Art of Being ‘Artistic’: Dutch Women’s Creative Practices in the Seventeenth Century,” which appeared in Woman’s Art Journal in 2001, made the salient point that even though Gesina ter Borch did not sell her work on the public art market, it did not lessen the intensity of her creative practice. Honig points out that the Dutch Republic of the 1600s was a society that was itself broadly creative and inclined toward art and other forms of visual culture. People were filling their homes and public spaces with art, design and decorative objects, and images of all kinds.

Gesina’s Introduction to Art

Gesina was the first child of her father Gerard ter Borch Senior’s third marriage. Gerard Senior was an artist himself, and he took great care with the artistic training of his sons, as evidenced by the scores of annotations and corrections that he marked on their drawings. However, only two of Gesina ter Borch’s drawings contain her father’s notes. Gesina thus probably did not receive the same kind of dedicated training from her father. She most likely learned to draw alongside her younger brothers Harmen and Moses while she also acted as their mentor. Because she was not seen as a potential professional artist-in-training but rather as a future wife and mother, Ter Borch began her artistic study relatively late, as a fourteen- or fifteen-year-old. In contrast, her brothers all began drawing as small children.

Ter Borch’s oeuvre consists of three large illustrated book projects, with each one more ambitious than the last. Her first album, titled the Materi-boeck, was begun while she was a teenager. It grew out of her study of calligraphy. She began her Poetry Album on November 18, 1652, a few days after she turned twenty-one. She completed the book about eight years later. She started her last known project, the large Art Book (Konstboek), in 1660, wherein she continued to compile both her own drawings and watercolors and the works of other artists.

Gesina and Gerard: Siblings and Collaborators

Gesina’s older brother Gerard ter Borch II was the most commercially successful artist in the family, and the only one of the siblings to pursue painting as a professional career. Gerard II and Gesina shared a close bond, despite their sixteen-year age difference (he was born in 1617 during their father’s first marriage). His oil paintings and her watercolors convey interrelated themes of courtship, romance, and domestic imagery, with a distinct focus on the inner emotional lives of everyday people. Gesina posed for her brother regularly, and the two must have discussed their work with each other. Their artistic exchange is most clearly and poignantly preserved in a jointly conceived and painted commemorative portrait of their younger brother Moses.

1667–1669. Source, Rijksmuseum

Moses was serving in the Dutch navy when he was killed in 1667 during a battle with English naval forces. The oil portrait along with two watercolor portraits by Gesina are filled with symbolic details alluded to Moses’s life and death—for instance, the snake that reaches toward him menacingly. Gerard II and Gesina most likely produced this painting for their immediate family as part of their personal process of grieving. Because of its unique circumstances, it is one of the most intimate and haunting portraits of either of their artistic careers.

The Play of Text and Image in Ter Borch’s Poetry Album

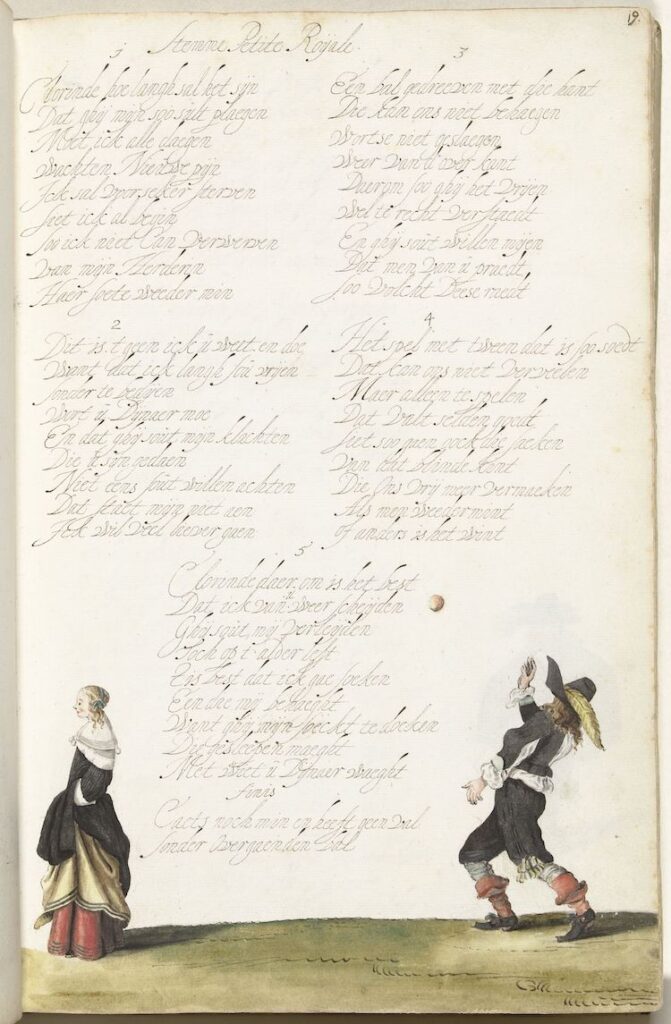

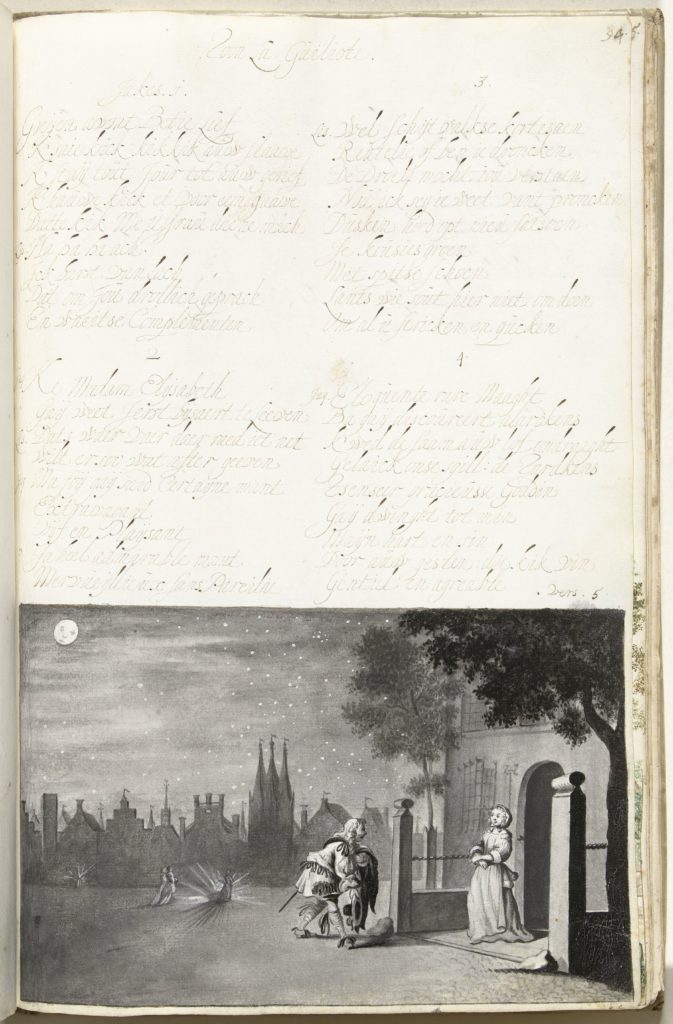

One striking feature of Ter Borch’s watercolor paintings is how she incorporated the hand lettered texts of the poems and songs that she transcribed, together with her visual compositions. In many of her works, figures stand, sit, walk, and dance along the white space of the paper as if they are floating along on the page itself. In other watercolors, especially later on in her life, Ter Broch would craft tiny worlds for her figures, with fully rendered backgrounds and atmospheric effects. These texts and images also carry on “conversations” with one another.

For instance, in this scene of a young man tossing a ball toward a young woman across the page, the ball seems like it might bounce right off of the script in between them. Take, as another example, this intimate scene of moonlit courtship.

Here, Ter Borch illustrated a poem by W. Schellinks, one of many love poems of the era that people regularly paired with popular melodies for singing. This poem features a lovelorn Spanish “Brabander,” a name for a type of man from the southern Spanish-controlled Netherlands. Brabanders, in the minds of the northerners of the Dutch Republic, were known for their French-influenced, over-the-top clothing and excessively refined manners. He has arrived at the doorway of a young woman named Elisabeth and is attempting to woo her in a mishmash of Dutch and French. Elisabeth pokes fun at his “droll speech and inflated compliment.” Elisabeth’s suitor begs “his Betty” for a kiss, but she finally sends him away, telling him to go back to his “Venus-birds” and to leave her alone.

Not only did Gesina capture the falling-over-himself eagerness of the young man and Elisabeth’s amused skepticism and self-composure, but she also evoked the culture of evening courtship and socializing that she would have seen in her immediate surroundings. The silhouette of a Dutch town appears in the distance, while three other groups of people promenade in the middle distance to the left of the main couple in the foreground. A star-filled sky stretches out above the town and the moon, anthropomorphized as a sweetly cartoonish man in the moon, looks down on the evening from the top left of the composition.

For a work that is so stylized and composed, Ter Borch’s ink study also evokes the sensation of standing outside on a moonlit night. Even the monochromatic palette seems to recreate the limited perception of color after dark. The small bursts of lantern light in the distance appear like tiny islands of illuminated activity in the larger darkness. Ter Borch’s sensitivity to the effects of cast shadows, sharp points of brightness, and silhouetted buildings is all evidence for her concentrated attention of nocturnal visual experience, in keeping with her wide-ranging artistic training.

Experimentation and Need for Further Study

Another, as far as I know, little-studied example of Gesina’s artistic experimentation is what appears to be a copy made by her after a Persian miniature painting, in the Konstboek.

It seems possible that Gesina may have felt an affinity for Persian miniature paintings, which share the intimate scale and refined linear design of her own style of watercolor painting. As with Rembrandt van Rijn’s studies after Persian miniature paintings, the care and attention to detail shown in the copy also demonstrates a Western artist’s interest in and appreciation for non-Western art. Far more study on this highly unusual work is needed.

The sheer variety and size of Gesina ter Borch’s body of work, along with her interest in experimentation and pushing the boundaries of her medium, would make one think that she would feature regularly in art history textbooks and exhibitions. Yet she is still relatively unknown outside of specialist circles of Netherlandish art history. The Rijksmuseum holds a wealth of her artworks, which they have now digitized and made freely accessible on their website, so hopefully this won’t be the case for much longer.

*Correction notice: The original post read Ger Luijten, rather than his brother, Hans Luijten. Also the original article had the artist’s birth year as 1633, rather than 1631. Thanks to Alison Kettering for alerting us to make these corrections.

Dr. Nicole E. Cook is an art historian with a passion for object-based study. She has experience in both academic and museum settings. Her research, teaching, and curatorial interests include early modern arts of Northern Europe, histories of early modern women artists and patrons, global contexts for Renaissance and Baroque art, the history of representations of night in art and visual culture, cinema studies, and object-based pedagogy.

More Art Herstory blog posts about Dutch woman artists:

Rachel Ruysch at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, by Erika Gaffney

Women and the Art of Flower Painting, by Ariane van Suchtelen

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

The Rijksmuseum Opens Its “Gallery of Honor” to Women Artists

Anna Maria van Schurman: Brains, Arts and Feminist avant la lettre, by Maryse Dekker

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

From a Project on Women Artists: The Calendar and the Cat Lady, by Dr. Lisa Kirch

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

A Clara Peeters for the Mauritshuis, by Dr. Quentin Buvelot

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

Women Artists of the Dutch Golden Age at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian (Guest post by Prof. Emma Steinkraus)

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): A Birthday Post

More Art Herstory blog posts:

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist (Guest post by Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy)

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration (Guest post by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London)

Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser: Founding Women Artists of the Royal Academy

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists (Guest post by Dr. Elizabeth Sutton)

The Priceless Legacy of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Curator’s Perspective (Guest post by Dr. Judith W. Mann)

‘Bright Souls’: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew (Guest post by Dr. Laura Gowing)

New Adventures in Teaching Art Herstory (Guest post by Dr. Julia Dabbs)

Renaissance Women Painting Themselves (Guest Post by Dr. Katherine A. McIver)

A Dozen Great Women Artists, Renaissance and Baroque

Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today? (Guest Post by Dr. Merry Wiesner-Hanks)

Thank you so much for this introduction!

Thank you for bringing readers’ attention to this little-known artist, Gesina ter Borch. One correction: Hans Luijten, rather than Ger Luijten (his brother), is the author to cite in one of your early paragraphs.

Alison M. Kettering

Isn’t it funny, how the painting “The Suitor’s Visit” by Gerard ter Borch the younger, her brother, is identical in thought and poses to Gersina’s earlier painting of a Man Courting a woman? Gersina is the woman in his painting and is said to have been the mastermind: https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.65.html

I was mesmerized by this post. Thank you so much for shining a light on this talented woman! I’m going to share the post with artist friends.

So glad to have this positive feedback on Nicole’s post! And there will be a book on this artist, Gesina ter Borch, in the new Lund Humphries series Illuminating Women Artists, though that volume is still a few years off.