A Review of Ingenious Women at Bucerius Kunst Forum

Guest post by Jenny Körber, Universität Hamburg

Introduction

Unlike their male colleagues, family members and friends, many early modern female artists have been forgotten despite their success and their remarkable careers. The exhibition Ingenious Women at the Bucerius Kunst Forum aims to counteract this shortcoming. By putting on display works by around 30 European female artists, in the context of art by their male relatives or mentors, the show offers insight into their artistic work and their exceptional biographies. (Fig. 1)

The forgotten lives of female artists: a few examples

Elisabetta Sirani

In the year 1656, the highly talented Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665) started to keep a “taccuino di lavoro,” a notebook in which she recorded her commissions. The successful Italian artist was only 18 years old at that time. A year earlier, she had already produced altarpieces for churches in the suburbs of Bologna. In the years that followed, her notebook grew continuously.

By the time of her early death in 1665, she had documented almost 200 paintings, drawings and engravings. The painting Omphale (Fig. 2) or her Penitent Mary Magdalene (Fig. 3), both on show in Hamburg, are proof of her great artistic talent and empathetic style. In 1660 the Accademia di San Luca in Rome listed her as a “maestra,” which certified Sirani’s status as a professional artist. She was able to run her own studio and teach students, which she actually did. Sirani took over her father’s workshop, where she herself was once educated along with two of her sisters.

She trained male—and presumably even female—artists with great success, hired journeymen and sold her paintings at high prices. At her funeral she was honored with an urban event in her hometown Bologna. Elisabetta’s mentor and biographer Count Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1616–1693) reported that the ostentatious funeral ceremony included an enormous catafalque with a life-sized sculpture of the artist (Fig. 4), music, and orations. She was buried in one of Bologna’s main churches, San Domenico. She was laid to rest next to Guido Reni, one of the city’s most esteemed artists both then and now.

Considering the high esteem for Sirani’s talent and the great success she gained during her lifetime, it seems almost unlikely that Guido Reni’s name is much more present in the art historical discourse than Elisabetta Sirani’s. How could such a remarkable artist disappear from the art historical canon for centuries? But as this exhibition highlights, Sirani is no exception.

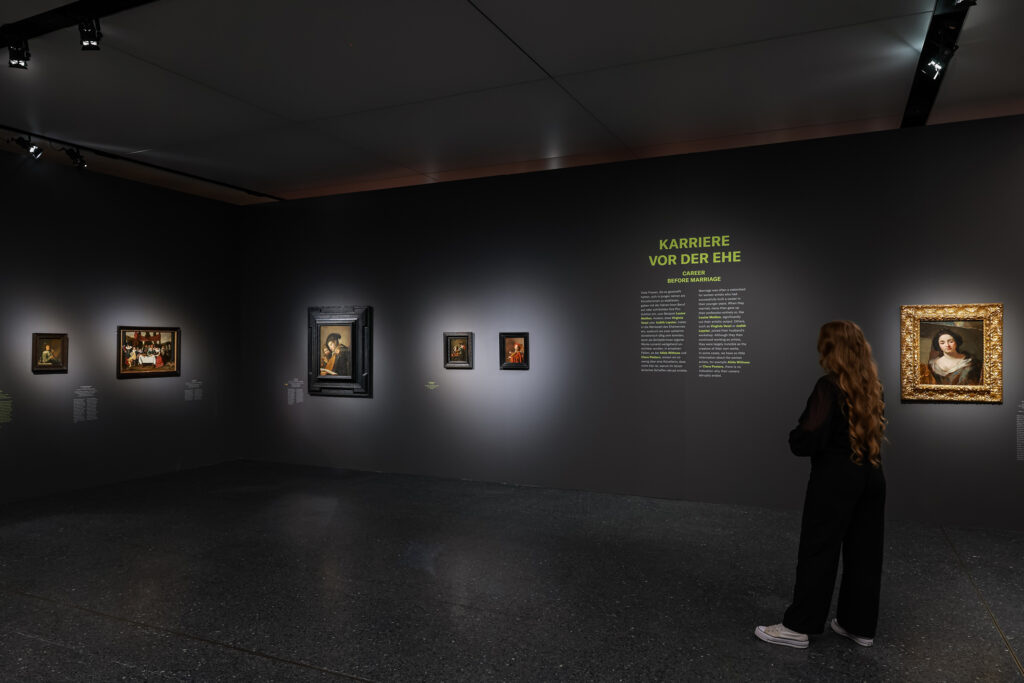

Mary Beale

Another example of a remarkable and nearly unknown career is the life of the British artist Mary Beale (1633–1699). Beale is considered to be one of England’s first female professional painters. Born into a household devoted to the arts, the young Mary came into contact with the art of painting at an early age. She did not give up her passion when she married the up-and-coming government official Charles Beale in 1652. Marriage was often a watershed for women artists. After they married, most of them gave up their profession or cut their artistic output significantly. The exhibition dedicates an entire section to these female artists and their early-stage careers. (Fig. 5)

Mary was an exception from this point of view. Even after her marriage she enjoyed a sterling reputation as a portrait painter. She also showed a talent for other art forms such as poetry. She collaborated with the poet Samuel Woodford (1636–1700) on The Paraphrase upon the Psalms (1667), which is considered one of Woodford’s major works. But that is not all: In 1670 Beale took over the position as the family’s breadwinner due to her husband losing his job. As a successful painter, she received numerous commissions while her husband ran the household and assisted her with her work in the studio. He took care of her appointments, registered her commissions, and primed her canvases. A self-portrait with her family depicts the artist and her husband as equal partners (Fig. 6).

Lavinia Fontana

The same is said about the career of Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614). While she earned money with her art, her husband actively supported her both in the back office and in caring for their children. A self-portrait of Fontana, that depicts her as a proud and multi-talented woman, is shown in the exhibition. (Fig. 7) The fact that these women and their almost modern lifestyles are highly unknown, shows the scope of Western art history, in which there was little, if any, room for female artists.

Female artists and their companions

The female artists featured in the exhibition were far from tragically misunderstood geniuses who were neglected by their peers. Instead, they were highly successful with their art during their lifetime. They were able to compete with, if not to surpass, the works of their male contemporaries. The still lifes of Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), for example, sold better than those of her husband. But only few women became independent artists or art teachers. Many of them were trained in the family workshop or in workshops under the guidance of male teachers. (Fig. 8)

The similarities between the works of teachers and their students proved to be a disadvantage for female artists and their legacy: art historians have mistakenly attributed many of their artworks to their male teachers or colleagues. For example, the works of the Dutch artist Judith Leyster (1609–1660), who was famous during her lifetime for her genre scenes such as the Funny Boozer (Fig. 9), were posthumously attributed to Frans Hals (1582–1666).

The show at Bucerius Kunst Forum brings the difficulties of attribution to the visitor’s attention. By juxtaposing the artworks by female artists with those of their male colleagues carefully, the exhibition brings both stylistic similarities and differences to the fore. A closer look at the painting Christ Among the Doctors (Fig. 10), originally attributed to Charles Wautier, shows that it was actually a collaboration with his sister Michaelina (1604–1689). Michaelina executed no less a figure than the young Christ himself.

Archduke Leopold Wilhelm was one of Michaelina’s greatest patrons. The court commissioned paintings from her, repeatedly, but none from her brother. The monumental history painting The Triumph of Bacchus, in which she depicted herself as a nymph (Fig. 11), is a testimony of her self-confidence. But Michaelina and Charles were no competitors. The two siblings lived together in Brussels and shared a studio there until death did them part.

Obstacles and creativity

Nevertheless, in comparison to their fathers, brothers, husbands, teachers and fellow-artists, women had few chances to pursue a life as a professional artist in the early modern period. At that time, women’s rights and career aspirations were regulated by men. Marriage prevented them from training for a profession or craft since a married woman was not supposed to work for a living. Only few art academies or guilds and confraternities admitted female artists. Therefore, there were even some art forms women were forbidden to execute.

The German artist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), for example, was denied membership of the painters’ guild in Nuremberg, which is why she was not allowed to paint in oil. Instead, she worked with gouache, thus circumventing the official regulations. The exhibition illustrates how female artists faced different conditions and how they overcame them successfully. Just as much as the art form, some genres were rated as not suitable for women. While the genre of history painting was regarded as inappropriate for the female gender, some women became eager to excel in other genres such as still lifes.

A basket of fresh berries (Fig. 12) by the French artist Louise Moillon (1610–1696) is proof of her excellent skills to portray nature. Thus, instead of relinquishing their careers women became creative. Other women overcame social obstacles solely by their talent and their ability to build a social network. This was the case with Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782) and Angelika Kauffmann (1741–1807) who were famous all over Europe and members of several art academies. Against all odds, Anna Dorothea Therbusch managed to join the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in Paris while Angelika Kauffmann was even among the founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Kauffmann’s self-portrait as Clio (Fig. 13), the muse of History, may be read as an appeal to rethink the way women are treated in historiography.

Women, men, and an appeal to rethink art history

Some visitors of the exhibition may find it questionable that the female artists are always presented alongside their male partners—be it their father, husband, or brother. The point of reference still seems to be the male artist, as he has dominated art history since Giorgio Vasari. But the aim of the exhibition is not to radically overthrow an old system. Instead, the show is an appeal to rethink art history by taking a comparative look at female art. By avoiding a confrontational approach, the exhibition eludes the danger of polarizing its visitors in advance. In return, the women’s works receive the appreciation they truly deserve. The show makes it evident that women have a justified claim to a permanent place in the art–historical canon. The female artists represented in the exhibition are not put on show because they belong to the female gender. They are put on display because their works are ingenious, and their lives are worth telling.

Ingenious Women: Women Artists and their Companions is on at Bucerius Kunst Forum through January 28, 2024. It moves to Switzerland in spring 2024, where it will run at the Kunstmuseum Basel from March 2 through June 30, 2024.

Jenny Körber studied art history, German Studies and literature in Münster, Paris, and Amsterdam and was a Junior Research Fellow at Harvard University in 2017. Her dissertation Innere Bilder–äußere Schau on the media dispositif of the early Jesuits is published by Böhlau (2024). She worked as a research assistant and curator for the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (2020–22) where she curated exhibitions on David Hockney and on the early modern Kunstkammer. She is currently a research associate (postdoc) at the University of Hamburg. Follow her on Instagram!

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Anna Dorothea Therbusch: A Woman Painting Against Eighteenth-century Odds, by Stephanie Pearson

Sofonisba Anguissola in Holland, an Exhibition Review, by Erika Gaffney with Cara Verona Viglucci

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu

Thoughts on By Her Hand, the Hartford Iteration, by Erika Gaffney

In defense of monographic exhibitions of female artists: The case of Fede Galizia, by Camille Nouhant

The Ladies of Art are in Milan, by Cecilia Gamberini

By Her Hand: Personal Thoughts and Reflections on an Exhibition, by Oliver Tostmann

Other Art Herstory posts you might enjoy:

Rachel Ruysch’s Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, by Lizzie Marx

Elisabetta Sirani’s Studio Visits as Self-Preservation: Protecting an Artistic Career, by Victor Sande-Aneiros

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Helen Draper

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

Lavinia Fontana: Italy’s First Female Professional Artist, by Elizabeth Lev

Elisabetta Sirani of Bologna (1638–1665), by Adelina Modesti