Guest post by Amy Lim, Curator of the Faringdon Collection, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire

Introduction

The Tate Britain exhibition Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain, 1520–1920 (16 May–13 October 2024) examines the ways in which women artists navigated a professional art world that was geared towards men. Some chose to confront the barriers head on. They campaigned for access to art schools, or tackled subjects (such as history paintings or nudes) that were considered inappropriate for women. Others charted a more subtle course.

Helen Allingham (1848–1926), one of the featured artists, does not at first glance appear to be a feminist trailblazer. Today, she is principally known for her picturesque watercolors of country cottages, familiar from jigsaw puzzles and biscuit tins. In their medium and subject matter, this is the type of art that Victorian society considered to be suitable for a woman. Such paintings are still often dismissed as merely pretty or sentimental. Yet in her lifetime, through a combination of talent, hard work and shrewd marketing, Allingham enjoyed immense critical and commercial success. She was also, for many years, a single mother, supporting her children through her art. For all the nostalgic prettiness of her watercolors, Allingham was a highly professional, pioneering woman artist.

Early years

Born Helen Paterson, and raised in Cheshire and Birmingham, Allingham’s early career was shaped by personal tragedy and financial hardship. When she was fourteen, her doctor father and younger sister died of diphtheria. After studying in Birmingham and the Royal Female School of Art in London, Allingham won a place at the Royal Academy Schools in 1867, but after two years, impending poverty obliged her to seek employment. Allingham preferred to work in watercolor, but with few opportunities to exhibit and sell, it was difficult to make a living from that medium, so instead she sought work as an illustrator.

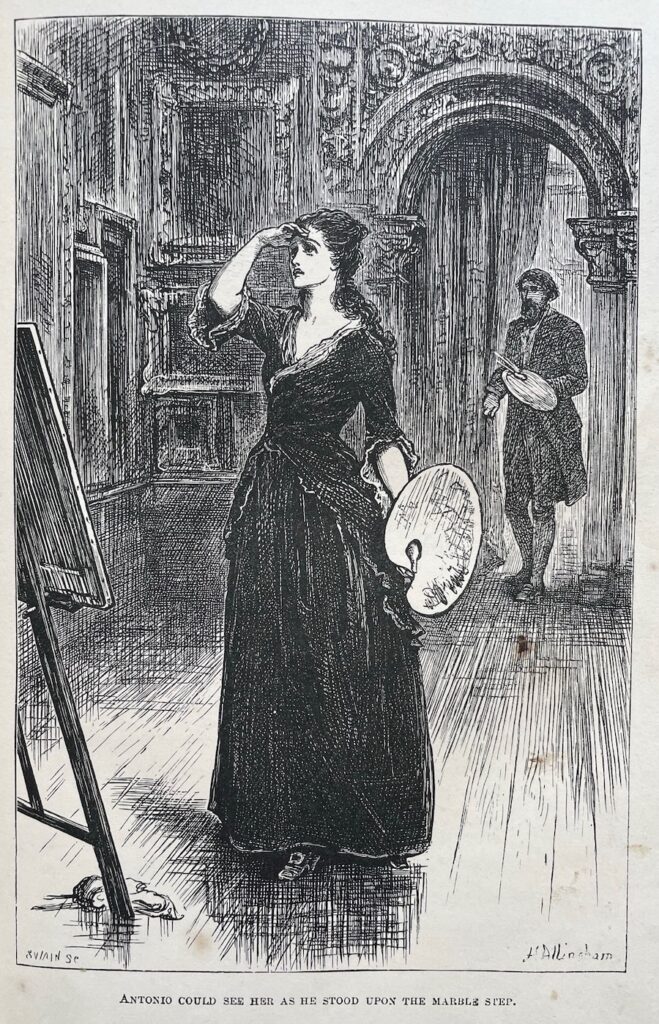

In 1870 she joined the staff of The Graphic (the only woman), which guaranteed her a regular income. Her drawings for the magazine made an impression on the young Vincent van Gogh. Allingham also illustrated serialized novels, including Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd and Anne Thackeray’s Miss Angel, a fictionalized romance about Angelica Kauffman.

Two events enabled Allingham to switch to watercolor painting, with which she would achieve phenomenal success. The first was her marriage to the poet William Allingham in 1874, which brought her financial security. Then, the following year, she was elected an Associate Member of the Society of Painters in Water Colour (then known as the Old Society, later the Royal Society). Her breakthrough work was The Young Customers.

This painting was watercolor version of a book illustration for Julia Ewing’s Two Flat Irons for a Farthing. It won her the notice of Society member Alfred Hunt, who helped her to select a portfolio and proposed her for election. She was elected at her first attempt, almost unanimously. This was a rare honor, especially for a woman, since only a handful of women were permitted to be members at any one time. Membership of this prestigious Society enabled Allingham to exhibit and sell her watercolors at their exhibitions.

Country cottages

In 1881, Allingham moved with her husband and children from London to the village of Witley in Surrey. Here, she began to paint the country cottages that would make her name. Her watercolors present a picturesque vision of English vernacular architecture: rambling, half-timbered and thatch-roofed, abundant with climbing roses, hollyhocks and apple-blossom. Allingham also painted domestic interiors, the local heathland, the flower borders in Gertrude Jekyll’s garden at nearby Munstead, and even scenes of Venice. However, it was her country cottages that were, and remain, her most popular works.

Allingham was startlingly successful. Her first dedicated exhibition, 66 watercolors of “Surrey Cottages,” was held at the Fine Art Society, Bond Street, London in April 1886. It sold out, so the Fine Art Society held a second exhibition, “In the Country,” also a sell-out. She would go on to hold a further five solo exhibitions with the gallery. By Allingham’s own reckoning, she exhibited and sold over a thousand watercolors during her career.

When her husband died in 1889, Helen Allingham once again became the principal breadwinner. This time, the popularity of her watercolors meant that she was able to support her family through the medium she loved. She worked dawn-to-dusk, six days a week, painting cottages close to home so that she could continue to look after her three children.

Happy England

Allingham’s success is often attributed to the nostalgic appeal of her subject matter. She painted a disappearing way of life, at a time of rapid mechanisation and urbanisation. Many of her patrons were Londoners, wistful for the countryside that they had left behind. Allingham’s paintings offered them an idealized version of rural life. Although realistic in technique, she selected the most picturesque elements of the cottages she painted, and omitted the harsh realities of rural poverty. She painted almost exclusively in spring and summer, and rarely showed manual or even agricultural labor. Neat-aproned women and rosy-cheeked children populate her paintings. They carry baskets, feed geese, or stand placidly at the garden gate.

Marcus Huish, the director of the Fine Art Society, encouraged this nostalgia through the catalogues and books that accompanied Allingham’s exhibitions. The catalogue of “Surrey Cottages” stirred up readers’ emotions by informing them that old English cottages were disappearing at a rate of 2000 a year. This nostalgia was a part of a broader movement responding to the rapid loss of England’s architectural heritage. Nine years earlier, William Morris and Philip Webb had formed the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. In 1903, Huish published a memoir (with Allingham’s collaboration), Happy England, illustrated with 81 color reproductions of her paintings. He made no apology for Allingham’s partial viewpoint, cheerfully admitting that her paintings offered “a mirror of halcyon days,” bringing happiness to workers “long in city pent.”

“Well-nigh perfect“

But to attribute Allingham’s success purely to nostalgia overlooks her exceptional skill. Modern art historians tend to avoid discussing quality, but Allingham’s talent was widely acknowledged by her contemporaries. The Art Journal’s review of her contributions to the 1877 Old Watercolour Society exhibition was unbridled in its admiration:

These certainly exhibit the greatest amount of true Art-workmanship on the least possible space of paper. They are gems in their way, and go far towards assuring the success of this year’s winter exhibition. “May” for instance … is to our thinking well-nigh perfect. So careful and accurate is its detail, and so marvellous its skilful drawing, that it deserves a covering of crystal … In point of wealth of artistic treatment and painstaking study, it will rival the best work in the room.

For many years, the critic John Ruskin was highly sceptical of women artists, but Allingham (among others) changed his mind. He especially admired The Young Customers, praising it as “for ever lovely – a thing which I believe Gainsborough would have given one of his own paintings for.” Allingham’s talent was recognized by her peers in 1890, when she was the first woman to be elected to full membership of the Royal Watercolour Society.

Allingham’s watercolors are just as lovely today. Her ability to capture the mossy undulations of a tiled roof, or the bright tangle of a herbaceous border, is as entrancing as it was over a century ago. To protect them from light damage, Allingham’s watercolors in museum collections are not usually on permanent display, but it is worth seeking them out when they are on exhibition. If you are not able to see them in person, high-res digital images can be a good alternative. Examples can be found on the websites of the V&A Museum and Birmingham Museums.

Dr. Amy Lim is part-time curator of the Faringdon Collection at Buscot Park, Oxfordshire, and a freelance art historian, lecturer and curator. She was a researcher for the exhibition Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain, 1520–1920, Tate Britain, 16 May–13 October 2024, with a focus on the Victorian era. Amy is a lecturer for The Arts Society, a curator at the Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham, and a tutor at the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education, and is currently preparing an online catalogue of the works of Gilbert Spencer RA. She has published articles and essays on the fine and decorative arts in Britain from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary