Guest post by Kristen Marchetti, Cole Fellow 2022–2023

Sarah Cole (1805–1857) was an accomplished American artist known for her paintings, etchings, and drawings. Like her brother Thomas Cole, an influential figure in the Hudson River School, she worked in the earliest years of the Hudson River School movement. She exhibited and sold her work nationally while living periodically at Cedar Grove, the property we know today as the Thomas Cole National Historic Site.

Over the course of the past year, I served as a Cole Fellow at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site. The Cole Fellowship is a residential program designed for postgraduate students to conduct original research and contribute to museum-wide initiatives, including developing exhibitions and interpreting site histories. For my research project, I chose to investigate the life and works of Sarah Cole.

Recovering Sarah Cole’s Life and Works

Cole is an under-researched figure in the history of American art. A selection of scholars such as Betty J. Blum, Haley Coopersmith, and Rowanne Dean have established a rich foundation of knowledge on Cole by revealing her biography, artwork, exhibition history, and artistic significance. My research on Sarah Cole synthesized and expanded past scholarship. I took a deeper look at how Cole’s life and artwork illuminated her artistic training and style, as well as her influences and the sociocultural environment in which she worked.

Valuable sources for understanding Cole’s life and career include her surviving works of art, immigration records and letters, and a selection of secondary publications. Currently, we know of thirty artworks by or attributed to Cole, of which sixteen have been located. Cole’s historical archive is supplemented by a collection of thirty surviving letters written by or to the artist over the course of her lifetime.

Why does Sarah Cole’s story and artistic output matter in the history of American art? In what ways does her career meaningfully connect to and diverge from that of her more famous brother Thomas Cole? These are the questions that I sought to answer in my research. In the context of art production in mid-nineteenth century New York, Cole is a case study of the many women artists who established careers as professional painters, drawers, and etchers at a time when the art world was becoming marginally more inclusive of women.

Transoceanic Beginnings

Cole was born in Bolton-le-Moors, Lancashire, England in 1805. She was the youngest of James and Mary Holloway Cole’s eight children. In 1817, Cole and her family left Bolton for Liverpool, a port city with a flourishing trade economy. Cole’s brother Thomas became an apprentice at an engraving shop in Liverpool, and it is possible that he took prints home to share with his sisters.

On July 3, 1818, the Cole family immigrated to the United States. After settling briefly in Pennsylvania and Ohio, the Coles moved to New York City in April of 1825. The city was becoming a hub for culture, commerce, and industry following the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. Thomas Cole quickly found success in New York as a landscape painter and established relationships with notable artists and patrons. As a result of Thomas’ budding connections and her own proximity to art institutions, Cole encountered a wealth of contemporary art in New York City. She frequented institutions such as the National Academy of Design, where Cole saw the paintings of influential artists at the forefront of New York’s art market.

At this time, artist organizations and institutions were still almost completely male-dominated. But professional opportunities in the arts were expanding for women in New York as institutions such as the New York Academy of Design’s Antique School began admitting women students. By 1837, Cole had begun her own painting career, and she regularly exchanged letters with her brother Thomas about painting subjects and techniques. On January 12, 1837, Cole wrote to Thomas: “…I have commenced painting, I am painting a little sunset original…” (see W.H. Bayless and Sarah Cole’s letter to Thomas Cole, January 10 and 12, 1837, Albany Institute of History & Art Library). This letter is the first record of Cole’s artistic production, marking the known start of her professional career.

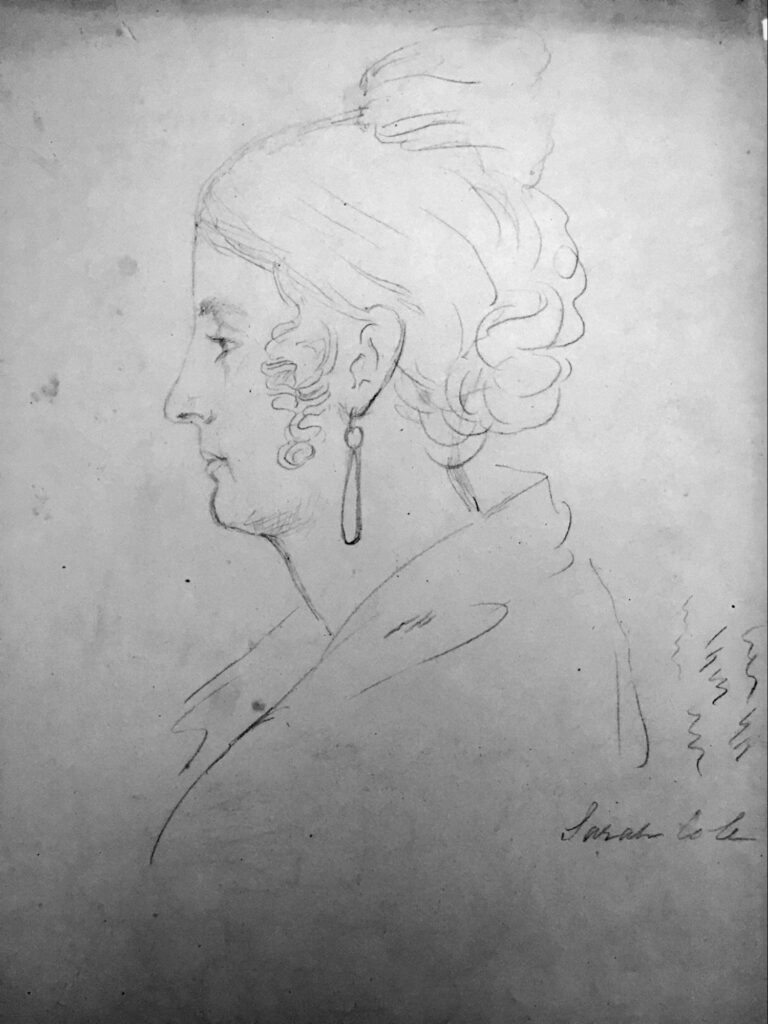

An Etcher, a Draughtswoman, and a Painter

By the time that Cole wrote to her brother in 1837, Thomas had settled in Catskill. Despite their separation, Cole and Thomas remained close confidants throughout their lives, and Cole offered Thomas advice on matters of art and life. In turn, Thomas promoted Cole’s artistic aspirations by sending her painting manuals and arranging for her to take etching lessons with artist Asher B. Durand (see Thomas Cole’s letters to Asher B. Durand from December 11, 1837 and December 18, 1839). In March of 1837, Cole wrote to Thomas: “…I think you had better bring down the copper plates + Etching apparatus when you come + we will talk things over + decide what I had better pursue…” (see Sarah Cole’s letter to Thomas Cole from March 15, 1837).

Cole’s desire to pursue etching preceded the rise of the women’s etching movement. In 1888, the Union League Club’s 1888 exhibition catalogue, Work of the Women Etchers of America, posthumously featured Cole and described her as the first woman etcher in the United States. Although none of Cole’s etchings have been located, the Detroit Institute of Arts owns an untitled pen and ink drawing by Cole that is a reproduction of an engraving by Jean Mathieu.

Over the course of her career, Cole reproduced numerous paintings by Thomas, likely as part of her artistic training and as a means of producing marketable works of art. In many of her reproductions, Cole incorporated novel elements or expanded Thomas’ sketches into finished oil paintings, as in Ancient Column Near Syracuse (c. 1848). In addition to reproducing Thomas’ works, Cole composed original compositions that include Landscape with Church (1846; see above) and Untitled English Landscape (c. 1846; see above).

A Nationally-Exhibiting Artist

On February 11, 1848, Thomas Cole passed away. His death was a tragedy for his surviving family, and it also stripped Cole and her family of their primary source of income. When Thomas died, Cole was living in New York City with her aunt, Lydia. From 1848 onward, Cole lived periodically with Thomas’ family in Catskill or with her sister Ann’s family in Baltimore.

The first four years after Thomas’ death were Cole’s most productive artistically. Most likely, Cole began to produce and market her artwork with more intensity to support herself and her brother’s family in Catskill. Cole exhibited and sold numerous works from 1848 to 1852 at the American Art-Union and the National Academy of Design in New York City, as well as the Western Art Union in Cincinnati and the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore. Works produced during this period include A Village in Arcady (c. 1848–52) and Untitled Seascape (c. 1848–52; see above).

The whereabouts of many works produced by Sarah Cole from 1848 to 1852 are unknown. Of Sarah Cole’s known paintings, two compositions stand out for the maturity of their technique and execution: Mt. Aetna, produced around 1846 to 1852, and A View of the Catskill Mountain House, produced in 1848. Cole painted these works nearly ten years after writing to her brother about her difficulties painting in 1837. The later oils-on-canvas showcase advanced application of paint, sophisticated use of light and shadow, and meticulously rendered details. Both are copies after paintings by Thomas Cole, although only the location of Thomas’ original A View of the Catskill Mountain House is known.

Later Years

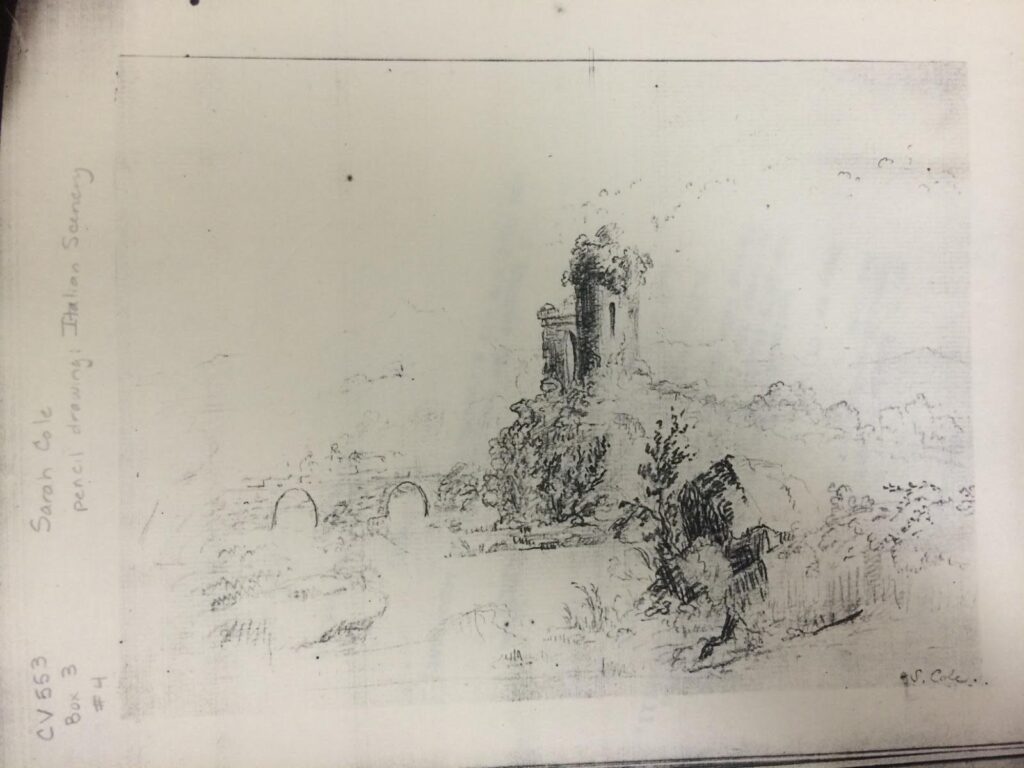

For unknown reasons, Sarah Cole stopped exhibiting her artwork publicly in 1852. It is possible that her sales were no longer satisfactory, or that she was shifting her attention towards other pursuits. Very likely, Cole continued to produce artwork after 1852, and she certainly maintained a keen interest in contemporary art and exhibitions. Undated works signed by Cole that she may have produced after 1852 include Untitled Genre Scene and Untitled (Italian Scenery).

Sarah Cole passed away in Catskill on January 6, 1857 at the age of 52. Her grave stands today in Catskill Town Cemetery, marking her life and lasting legacy at Cedar Grove. As one of the first Hudson River School painters and one of the first women printmakers in the United States, Sarah Cole shaped critical movements in American art. She also paved the way for subsequent Hudson River School artists, such as Susie Barstow, Frederic Church, and Mary Nimmo Moran. Like other women in Victorian society, Cole was primarily responsible for servicing the needs of her family (see Betty J. Blum, “Copyists After Thomas Cole”). Domestic and familial duties often distracted Cole from artistic pursuits, as she discusses in letters to Thomas, but Cole nevertheless persisted in her career to become a professional, exhibiting artist with patrons across the nation.

Today, the omission of Sarah Cole from twentieth- and twenty-first-century exhibitions and publications on the Hudson River School testifies to persistent gender biases in art history. My research this year sought to expand the canon of the Hudson River School to include one of its earliest members: a woman who sold and exhibited her paintings and etchings in the same circles as other leading artists of her time.

Kristen Marchetti is an emerging museum professional interested in curatorial studies, women’s history, and medieval arts. As a Cole Fellow at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in 2022–2023, she conducted original research on the life and career of Hudson River School artist Sarah Cole, culminating in a final paper (available upon request*), public presentation, and research archive. She also contributed to collections and curatorial initiatives, including serving as an Assistant Curator in the exhibition, Women Reframe American Landscape: Susie Barstow & Her Circle/ Contemporary Practices at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site. She graduated from Brown University in May 2022 with concentrations in the History of Art and Architecture and Visual Art, and she will be pursuing her Master of Arts degree in the History of Art and Archaeology at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University starting in September 2023. Follow Kristen on LinkedIn!

*If you are interested in reading Kristen’s research paper on Sarah Cole, please contact her at kristen.marchetti@nyu.edu.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely

I never knew about Sarah being a Catskill Mountain painter only about brother Thomas’ works. We need to know more about women artist of the early eras. Thanks