Guest post by Lili R. Ott

A Woman Artist of the Hudson River School

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck is one of the unsung women artists of the Hudson River School. Focused on the American landscape at its picturesque and patriotic best, the Hudson River School was the first native art movement in the United States. Its defining artists—Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt—were male, and even today, the Metropolitan Museum of Art refers to the Hudson River School of painting as a “fraternity.” But there were also many women, both professional and amateur artists, who painted in the same style with similar subjects and lived in the same mid-Hudson towns. Until recently, their names and their work have been ignored or unknown. But in the last decade or so, scholarly interest has begun to focus on the women of the Hudson River School.

Background

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck left a legacy of artistic accomplishment. Born in 1841, she was the fifth of nine children of Hudson riverboat captain George Seymour and his wife Julia Roraback Seymour. Her mother had deep Hudson Valley roots stretching to the earliest Dutch settlements. Laura grew up in the bustling town of Hudson, population 6000. Her family’s home on Warren Street was in the town center in the midst of activity and commerce.

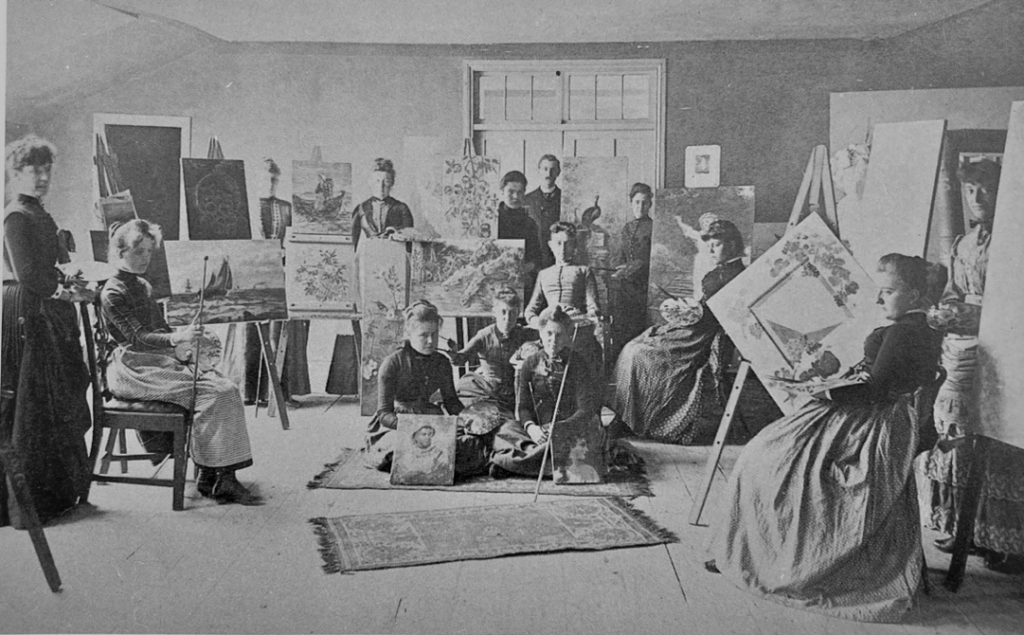

Art Education in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

Laura attended the Hudson Female Academy which trained young ladies from the region to be accomplished wives and mothers. She studied Latin, Roman History, Trigonometry, Rhetoric and Composition, French, Music and most importantly, in her senior year she studied Drawing and Painting in Water Colors and in Oil. Her teacher was Hudson River School artist Henry Ary, who exhibited at the National Academy of Design. Ary’s mentor was Thomas Cole. He sketched with his friend and fellow Hudsonian Sanford Gifford and also taught and mentored John Bunyon Bristol and other Hudson River School artists.

Ary hosted exhibitions and ran an art store directly across the street from Laura’s Warren Street home, the only shop for art supplies in Hudson at the time. We can imagine that the space was a gathering place for the local artists to meet, exchange news, discuss their work and buy their oils and brushes, canvases, and varnish. As Henry Ary’s pupil, neighbor and family friend, Laura was likely part of the activity.

An Early Exhibit

After Laura graduated from the Academy in June 1858, she lived in the family home with her mother, grandmother and six of her siblings where she continued to paint. In April 1864 she participated in a Civil War benefit fair sponsored by the Ladies of Hudson for the Relief of the Families of Volunteers. She was one of only five women artists listed in the show of 62 works exhibited in its Picture Gallery. The male artists represented included Frederic Church, Arthur Parton, Henry Ary, Worthington Whittredge and Sanford Gifford.

Family Changes and Inspiration

Soon after, she married John Atwood, a Civil War soldier. They had two children: a son, Elbert, in December 1865, and a daughter, Lilian, in September 1873. The marriage was not a happy one, and she was soon back in her family home where she continued to paint.

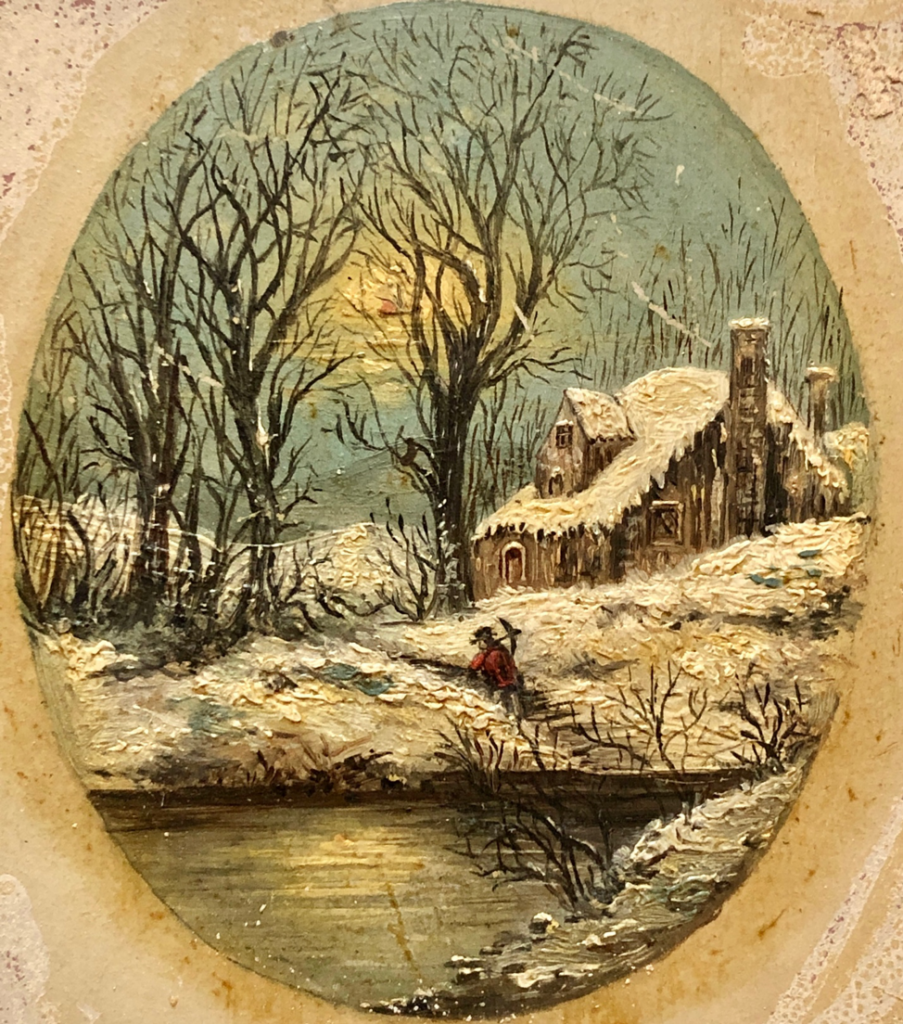

Laura was inspired by the nature around her, whether the autumn colors of Columbia County or the ocean she saw on visits to Long Island. Her work shows the same romantic sensibility and love of landscape and distinctive treatment of light that characterizes the work of male Hudson River School artists. None of her watercolors survive, but her oils show her mastery of detail with both brush and palette knife techniques. Her paintings often depict a single figure or small group of people in a larger, peaceful natural world. Unlike Frederic Church and other Hudson River School artists who traveled to more exotic locales for their inspiration, Laura never traveled outside New York State.

A New Art Form

In the 1870s, Laura began decorating china. Many Hudson Valley women painters, such as Thomas Cole’s and Frederic Church’s daughters shared the china-painting fervor, which was a socially acceptable activity for women. The late nineteenth century saw the publication of books and magazines with examples and specific instructions about this art form. Classes and clubs for decorating sprang up. Art supply stores both in urban areas and smaller towns such as Hudson sold glazed porcelain blanks, enamels and brushes, and portable kilns for firing the finished china.

Laura’s extant work from this time includes cups and saucers, and dessert and serving plates, primarily on Limoges china, although also on china from other European makers. Her patterns seem to be her own although they are influenced by the available printed sources. She used naturalistic designs of flowers and leaves on most of her work although one chocolate set has more stylized geometric patterns. All were gilded, glazed and fired.

An Independent Woman

Divorce was uncommon in Laura’s place and time. But Laura did divorce her husband and eventually move into her own home. In June 1880, Laura Atwood was in her mother’s house. But by 1882, she had moved to 3 Prospect Street, still in Hudson, but several blocks away. And by 1888, she is the only person listed in the Hudson Business Directory as “artist” with the address at 62 Short Street. Since her house is on the corner of Short and Prospect streets, it may be that the studio and gallery entrance was on the Short Street side and the family entrance was on the Prospect Street side. Family lore suggests that Laura was successful in selling her art. Although she did have family money, the profits from her work allowed her to live and work on her own and support her children.

Laura exhibited locally, but she also represented Hudson’s artistic community in more far-flung venues. In 1891, The Columbia Republican newspaper published a review of the Exhibition Hall at the New York State Fair in Syracuse with this report: “Mrs. Laura Atwood, of this city, also kindly loaned for the occasion a specimen of her skill with the brush in a picture that showed a cluster of roses in all their variegated hues and so perfect were they that one could imagine that he were inhaling their fragrance.”

A New Life in her 50s

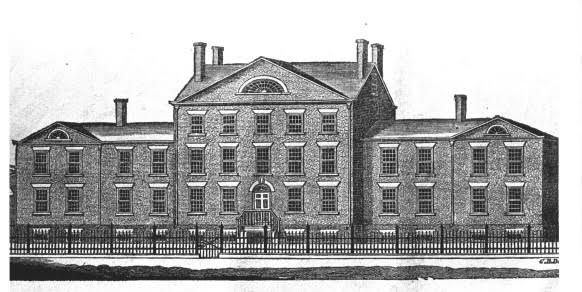

Laura visited New York City often because her sister lived there. On one of her visits, she met Frank Hasbrouck, owner of a large wholesale grocery business. They married in August 1892. They lived part-time in his house on Riverside Drive in Manhattan. In 1898 they purchased Doric Hall—a home overlooking the Hudson in Greenport, abutting the City of Hudson—as a summer residence.

Laura’s younger child took the name of Hasbrouck. Sadly, Frank died the following year, in 1899; and Laura herself died in June 1900 at “her fine residence at the outskirts of the city in the Town of Greenport,” according to her obituary in the Columbia Republican (June 14, 1900, p.5).

It noted her philanthropy: “…[S]he had a kind and sympathetic nature, and while living in affluence on her fine estate, was not forgetful of the needy who appealed to her for assistance and her many charitable deeds will not be forgotten by those who were the recipients of her generosity.” Her obituary makes no mention of her art, which perhaps shows her wealth and good works ranked higher in the reporter’s eyes.

Loss and Legacy

Five years after her death, Doric Hall was destroyed by fire. Laura’s diaries, record books, art supplies and many of her paintings—a lifetime of artistic work—were lost. Laura’s daughter, Lilian Hasbrouck Green, lived on the Doric Hall property every summer until her death in 1955. She distributed her mother’s remaining paintings and decorated china to her own seven children and her many grandchildren.

Laura’s work provides a legacy of artistic accomplishment at a time when few career paths were open to women artists—and even fewer that allowed them to earn money. She was surrounded by the work of Hudson River School painters as well as by the natural beauty of the Hudson Valley itself. Laura Seymour Hasbrouck was not related to any Hudson River School artist, nor did she exhibit or work in Manhattan. Even while living primarily in one town, with the responsibilities of family and the mid-nineteenth-century expectations of acceptable feminine behavior, she was able to fulfill her own creative drive and leave a legacy of artistic talent and accomplishment. Her work is worthy of study today and provides another example of the importance of recording and celebrating female artists, past and present.

Lili R. Ott became interested in the Hudson River School as a teen working as a tour guide at Olana, home of Frederic Church, as well as by growing up in a family steeped in art. She received an MA in Museum Studies from the Cooperstown Graduate Programs, SUNY Oneonta. Among other jobs, she was Historic Site Manager of Mills Mansion, Staatsburg, New York, Director of Historic Houses at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Director of Concord Art Association in Massachusetts. She lives in mid-coast Maine where she writes about local history. She is the great-granddaughter of Laura Seymour Hasbrouck.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

The Cheerful Abstractions of Alma Thomas, by Alexandra Kiely