Guest post by Jennifer Dasal, creator and host of the ArtCurious podcast

The proposal of either Sculpture or Suffrage… in all my recollections the two are so involved with each other that I think I shall not be able to extricate them.

—Alice Morgan Wright, “Sculpture and Suffrage,” New York State Business & Professional Women (1947)

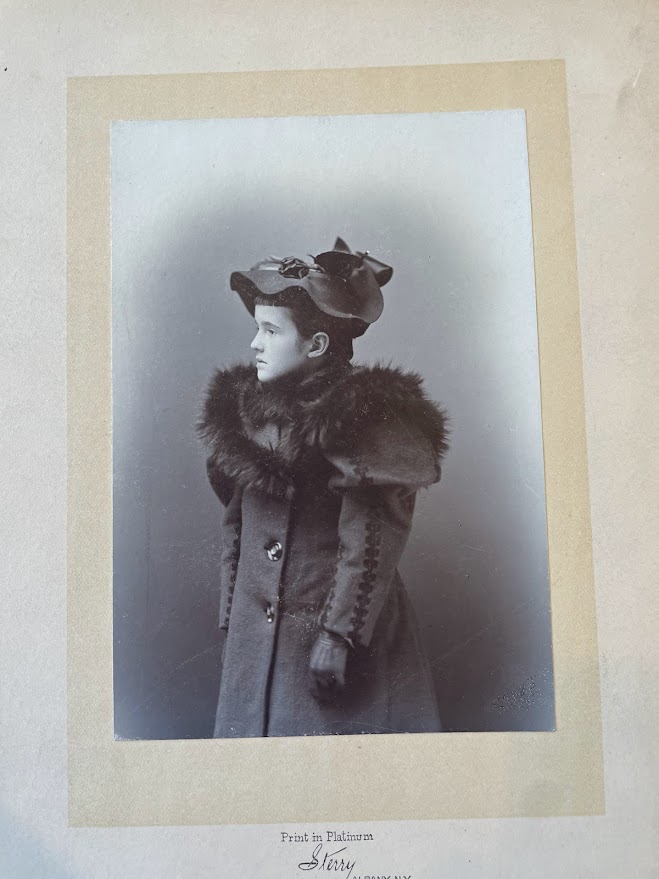

Alice Morgan Wright (1881–1975) was not one to take “no” for an answer. Polite, sure, but driven—always. She was nothing if not dedicated to, and passionate about, her goals.

Take, for example, a defining moment in her early art education. The Art Students League in New York City, where Wright studied around 1907 or 1908, forbade women to participate in life-drawing classes featuring male models. She was angry, naturally—she needed the experience of drawing male anatomy to create realistic pieces!—but more importantly, she was tenacious and resourceful. She’d find a workaround.

Within days, Wright began frequenting amusement halls and athletic clubs, where she sketched boxers and wrestlers mid-bout. She ignored the scores and studied straining muscles and sweat-slicked skin, translating them into quick charcoal sketches. If the League wouldn’t let her study the male form, she’d study it ringside.

That was Wright in a nutshell: a tenacious artist who met her challenges, in both art and life, head-on.

Early Years and Artistic Development

Alice Morgan Wright, born in Albany in 1881, exuded independence and self-confidence from an early age. A childhood event inspired her lifelong love of art. After swiping a slab of paraffin, she wielded a jackknife to carve a pint-sized figure of an elephant. Stunning and delighting her parents, Wright was equally transformed. She later confessed that, in that moment, she determined that she would become a sculptor.

And that she did. After graduating from Smith College in 1904, Wright settled in New York City to study at the Art Students League. There, she garnered acclaim at local art exhibitions and student competitions. She won, for example, a “general scholarship for best figure in modelling [sic] classes” in 1908 (her fellow League attendee, Georgia O’Keeffe, received the “general scholarship for still life painting” at the same event).

By 1909, though, Wright had pursued her education as far as she could within the United States. For women, gaining prominence as a sculptor was complicated, partially due to unfair gender politics. Artists long considered sculpture a determinately masculine medium. Even finding appropriate instructors to mentor a budding sculptor was a challenge for a female artist. In addition, a significant coterie of the country’s most respected sculptors of the era, like Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Frederick MacMonnies, decamped to Europe during this era. Wright, then, made the logical choice: in September 1909, she sailed to France, remaining there until 1914.

A Feminist Awakening

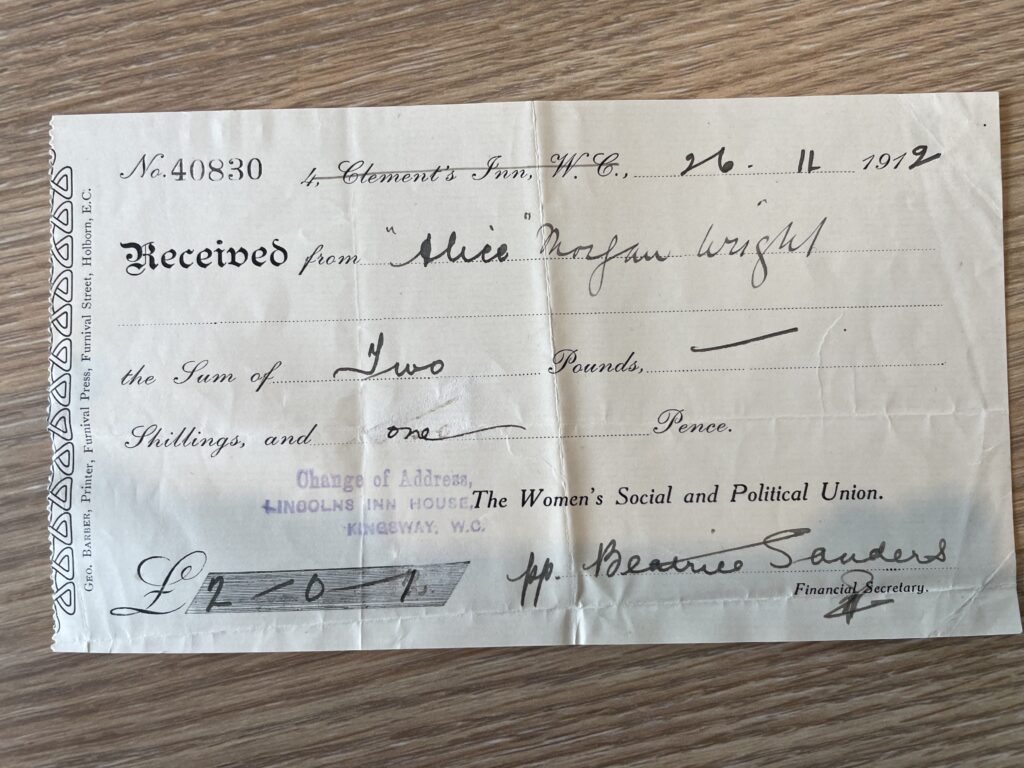

Always industrious and highly motivated, Wright centered herself in the Parisian art world at a quick pace. After only a few months, however, art was about to take a major backseat. In December 1909, Wright met 51-year-old British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Given Pankhurst’s prominence, Wright was already familiar with her, and Wright’s letters to friends bubble over with poetic excitement at their formal introduction. “I started out with the sentiments of one who might have [been moved] by the stirrup of Joan of Arc, touching the ‘hem of her garment,’” she wrote.

Stirred by the older woman’s grace and determination, Wright became a card-carrying member of the WSPU. Her Parisian days, once marked by the rhythms of an art student’s schedule, morphed. So focused had she become on the suffrage movement that she considered pursuing it as her life’s primary work, even dropping her art career in its favor. Suffrage or sculpture? The question boggled her and became an ever-increasing frustration.

It turns out that Emmeline Pankhurst advised Alice Morgan Wright on this matter. In early 1912, Wright confessed her indecision to Pankhurst, who responded unequivocally. “[S]he told me… to stick to my sculpting and stay out of causes,” Wright recalled. But she did not take this advice to heart. “Two months later I was behind bars in Holloway.”

Alice Morgan Wright Goes to Jail

British and American suffragists followed Pankhurst’s dogmatic “deeds, not words” decrees. They clashed with the police in protests that often resulted in violence and arrests. Once imprisoned, women participated in hunger strikes, a strategy sanctioned and performed by Pankhurst herself.

Library of Congress.

A report in spring 1912 spurred Wright to her greatest action yet. After learning of the British Parliament’s continued refusal to grant suffrage, Wright felt she could no longer watch from the sidelines. As she later noted:

Desiring to take part in the movement, I hurried to London and volunteered my services… I simply desired to share in the protest against the dishonorable treatment of women’s demands. Our cause is not merely national: it is universal.

She arrived in London in the morning hours of March 4, 1912. That afternoon, she departed her hotel alongside two other suffragists, their pockets filled with stones. As they joined a cadre of several hundred women, one of Wright’s friends threw a rock at the window of a nearby post office, smashing it. The scene then erupted in chaos: the police detained 200 women that day, and though Wright was adamant that the stones in her own pockets had been unused—“I hadn’t really smashed anything,” she asserted—she, too, was arrested, sentenced the very next day to two months of hard labor at Holloway Gaol, the largest women’s prison in Western Europe.

23, 1912: 4.

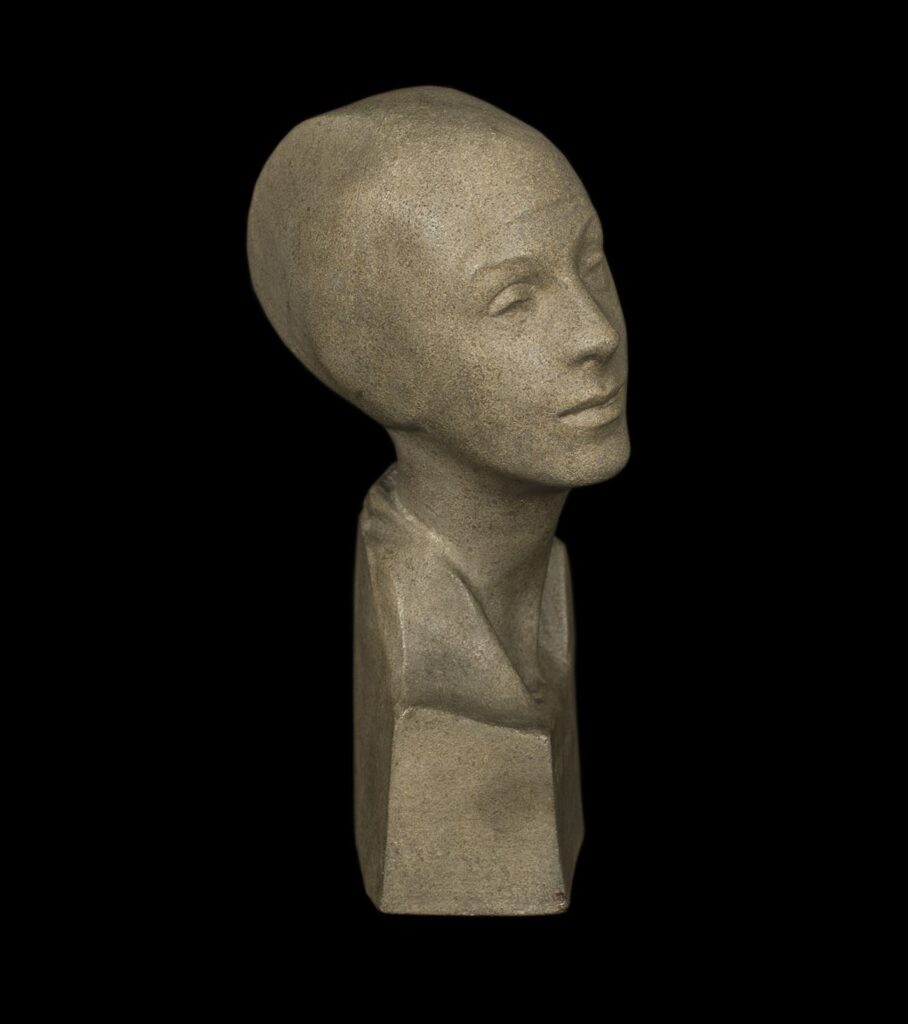

In the crush of prison processing, Wright smuggled in some pencils tucked inside her stockings, a sketchbook, and—impressively! — “a few pounds of plastoline,” or modeling clay. These art materials provided crucial distractions as well as documentation of her brief time in jail, which she called “monotonous, but not especially unpleasant.”

Of Wright’s surviving works from her Holloway imprisonment, several are small portrait busts of Emmeline Pankhurst herself. The most striking iteration presents the suffragist as an ageless sylph with smooth skin and downturned eyes. Her head is tilted in an insouciant manner upon a long and graceful neck. A wrap or scarf covers Pankhurst’s hair, and her lips look full and soft—she is beautiful. Wright pulls off an incredible feat, elevating her contemporary subject into a timeless heroine suffused with elegance and dignity. It is a clear indication that she spent much of her Holloway sentence thinking about Emmeline Pankhurst, with her emotions moving into a realm of “queer adoration,” as one historian notes.

A Return to Paris

Alice Morgan Wright exited from Holloway in late spring of 1912, though she had been offered an exit deal at least once, if not several times, during her incarceration. If she signed an affidavit confirming her guilt and promising not to participate in future suffrage meetings or protests, she could leave Holloway immediately.

Surprising no one, Wright refused to sign.

After her eventual release, the artist returned to France and settled back into a version of her previous role as “Parisian art student.” But her suffrage experiences and prison stay had changed her, and activism thus remained her primary focus. It was the title of activist— not sculptor, nor even artist— that she wore proudly for the rest of her life.

The Mature Period

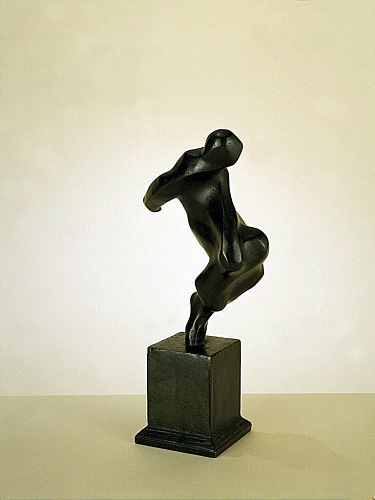

Not that Wright gave up art entirely—at least not right away. Prior to departing Paris to return to the United States in 1914, she exhibited her work at several prominent exhibitions. Back in New York City, she completed several commissions, and presented her work at the prestigious Modern Art Gallery—an extension of the 291 Gallery helmed by Alfred Stieglitz—where she exhibited alongside the likes of Amadeo Modigliani and Constantin Brâncuși. The modern artist Arthur B. Davies even purchased one of her sculptures, Wind Figure (1916). All of this is ample evidence of both Wright’s amazing abilities and the positive critical reception of her work. It also confirms Wright’s standing as among the best avant-garde sculptors of the era.

Her artwork reached the pinnacle of its strength and panache in the late 1910s. By that time, Wright had synthesized the vast number of artistic styles she witnessed during her years in Paris—particularly Cubism and Futurism— and experimented with a very modern direction. She created figures dancing with movement and vigor. And while her Paris works were more solidly indebted to Rodin, these pieces echoed no particular master. There is a little bit of Picasso here, some Duchamp-Villon there. Yet Wright never went fully abstract. Her works grew more abstract but always retained a reliance on the human body.

17 in. Albany Institute of History and Art, gift of Elinor Wright (Mrs. Clark) Fleming, cousin of the artist, 1978 (1978.21.2).

And when she combined this aesthetic strength with her political engagement, the effect was propulsive. The Fist, a painted plaster masterwork from 1921, features a swirling abstracted hand clenched in triumph. The piece, completed one year after women finally gained the right to vote in the United States, is a victorious celebration of force and fortitude. It is a powerful testament to the joy the artist likely felt after achieving her hard-won goal. It is a testament, too, to Alice Morgan Wright herself, and an ideal stand-in for such a talented and uncompromising firebrand.

22 in. Albany Institute of History and Art, gift of Elinor Wright (Mrs. Clark) Fleming, cousin of the artist, 1978 (1978.21.3).

Later Life and Critical Appraisal

Some might argue that Alice Morgan Wright’s story begins and ends with activism with a little sidestep into sculpture in the middle. While Wright found acclaim for her art career in the States, it often fell by the wayside in favor of other interests. After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 granted American women the right to vote, Wright’s sculpture career picked up speed, but only briefly. Returning home to Albany after several years in New York City, she established an art studio on the top floor of her childhood home. She ceased creating new work by around 1930, however, and no longer exhibited after 1940.

in. Albany Institute of History and Art, gift of Elinor Wright (Mrs. Clark) Fleming, cousin of the artist, 2004 (2004.1.20).

Alice Morgan Wright’s animal activism is what she—along with her life partner, Edith Goode—is most known for today. In her final decades, she became the chairman of the International Relations Committee for the National Humane Education Society (NHES). In that capacity she led several initiatives for animal welfare at the United Nations. Closer to home, she and Goode purchased acreage in northern Virginia, where they founded Peace Plantation, an animal refuge. Her love of animals was a passion she pursued until the very end. After her death at age 93 on April 8, 1975, the majority of Wright’s $3 million estate was given to the care and protection of animals.

Alice Morgan Wright’s sculptures continue to grow in esteem among curators, historians, and museumgoers. A cache of her works may be viewed at the Albany Institute of History and Art. Her work is also present in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Folger Shakespeare Library, both in Washington, DC. The Museum of London holds a bronze cast of one of her Holloway sculptures of Emmeline Pankhurst.

Author biography

Jennifer Dasal is the creator and host of the ArtCurious podcast, which has been featured in multiple local and national publications and websites, including O, the Oprah Magazine, PC Magazine, ArtDaily, NPR, Salon and more. She is also the author of ArtCurious: Stories of the Unexpected, Slightly Odd, and Strangely Wonderful in Art History. Her second book, The Club: Where American Women Artists Found Refuge in Belle Époque Paris, is due out in July 2025 from Bloomsbury USA. She holds an MA in art history from the University of Notre Dame and a BA in art history from the University of California, Davis. Dasal is the former curator of modern and contemporary art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, where she worked for thirteen years. She lectures frequently on art both locally and nationally.

More Art Herstory guest posts you might enjoy

Emma Stebbins, Anne Whitney and Vinnie Ream: American Women Sculptors of the Nineteenth Century, by Maria Ausherman

A Quiet Eye—The Unique Achievement of Sylvia Shaw Judson, by Rowena Loverance

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattler

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Minnie Jane Hardman | An Introduction, by Hannah Lyons

The Life and Art of Dorothea Tanning, by Victoria Carruthers

Dalla Husband’s Contribution to Atelier 17, by Silvano Levy

Deirdre Burnett: A Significant British Ceramic Artist Remembered, by Jo Lloyd