Guest post by Nancy Siegel, Towson University

An artist of the Hudson River School, Susanna (Susie) Moore Barstow (1836–1923) was raised in the upper-middle-class family of a well-respected tea merchant. She maintained a studio in Brooklyn (fig. 1) that was certainly well known to many. In the December 28, 1890 issue of The Brooklyn Citizen, an art critic described it, in unintentionally pejorative language, as Miss Barstow’s “dainty little studio.” Barstow was inspired by the outdoors. She frequented the Catskills, the Adirondacks, the White Mountains, and the lakes and mountains of Maine for inspiration. She made multiple excursions abroad to study art in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. And, she took a trip around the world in 1901 to Japan, China, India, and Egypt with her partner, Florence Nightingale Thallon, a fellow artist with whom she frequently lived and traveled for nearly two decades.

Barstow was also an inveterate hiker. In the August 3, 1889 issue of the White Mountain Echo, reporter Emily A. Thackray noted that she had climbed up to 110 peaks, including “all the principal peaks of the Catskills, Adirondacks, and White Mountains, as well as those of the Alps, Tyrol, and Black Forest, often tramping twenty-five miles a day, and sketching as well, often in the midst of a blinding snow-storm.”

Recovering Barstow’s legacy, a hundred years on

By all accounts, Barstow’s artistic legacy was well established at the time of her death in 1923. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle characterized Barstow as “one of the best-known Brooklyn artists,” and when she died, an obituary in the same newspaper described her as a “prominent landscape artist, whose paintings won her wide renown” (fig. 2) and as a “woman of keen intellectual attainments.”

Yet, within a mere few decades, her achievements and reputation, along with those of fellow women artists, were written out of history. In an unexplainable moment of art-historical amnesia, exhibitions on American landscape failed to include the works by women of the Hudson River School such as Barstow. With very few exceptions, these female painters were all but forgotten; art historians neglected to mention them in catalogues, monographs, and essay collections. This historical scholarly bias against their abilities continued well into the twentieth century. In recognition of the 100th anniversary this year of Barstow’s death, now is the perfect moment to bring her art and life back into the narrative of American art.

Training and early career

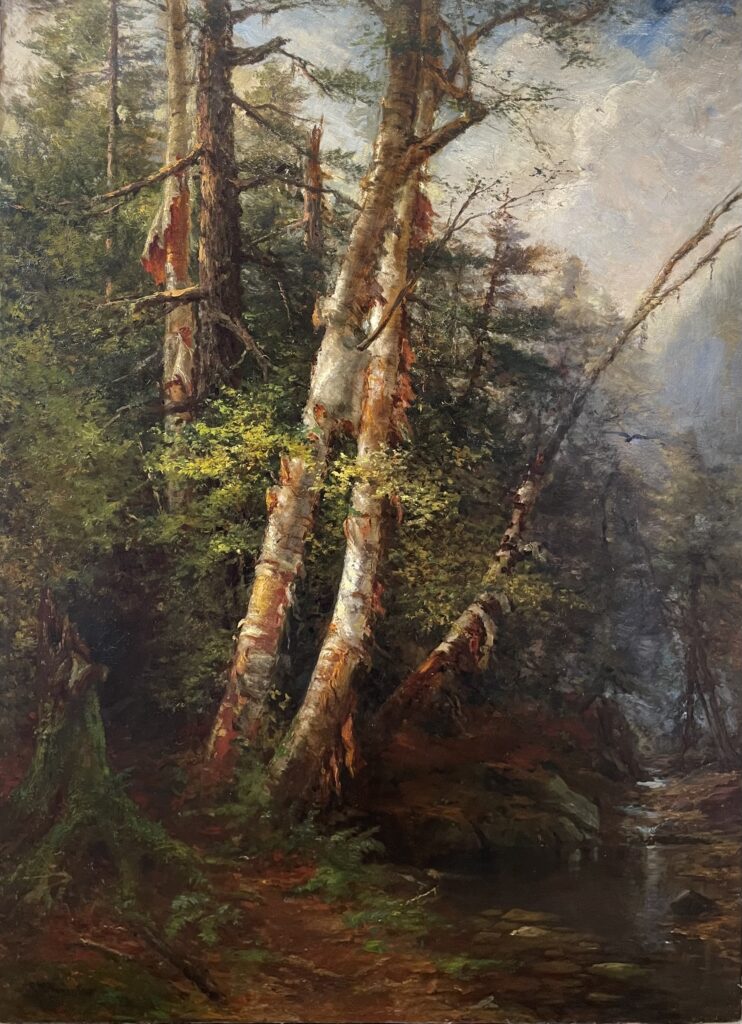

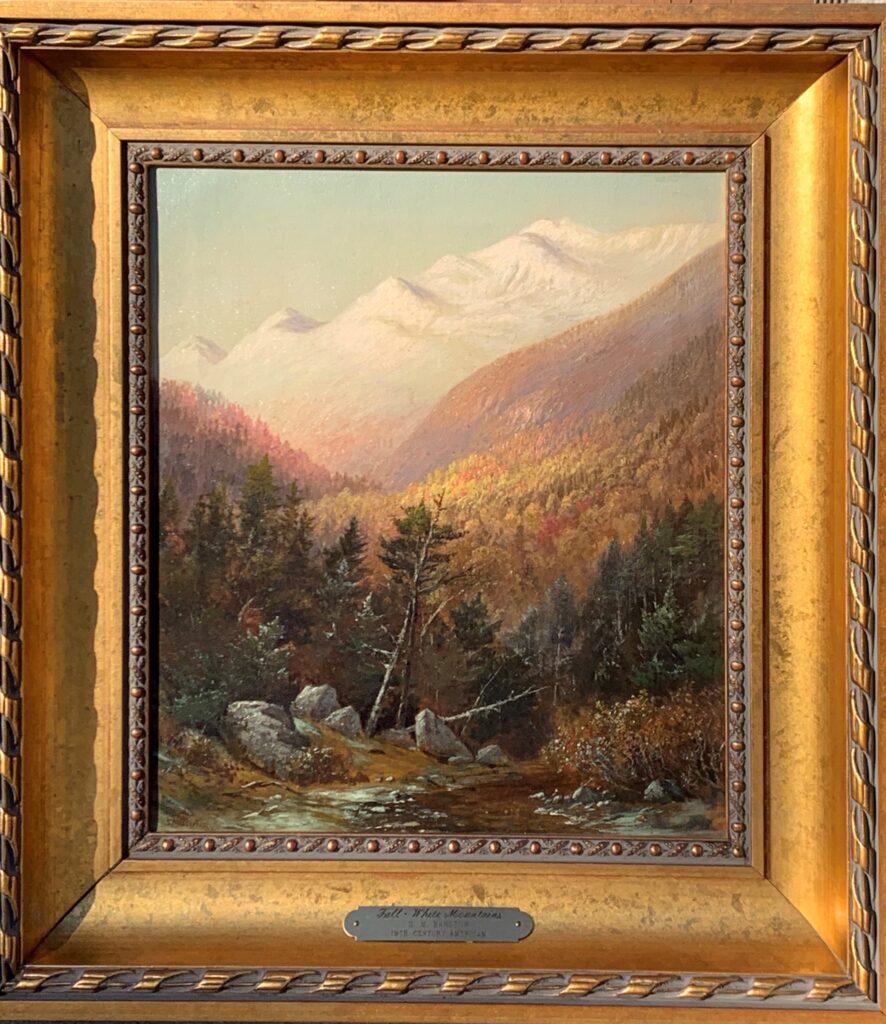

After attending the Rutgers Female Institute (1853) and the Cooper Union (1861), Barstow began exhibiting her work in her twenties. She joined the important art organizations of her day, such as the Cosmopolitan Art Association. The early style of her painting can be characterized as that of the Hudson River School (fig. 3)—romanticized, site-specific compositions with secluded depictions of nature’s beauty. As a professional artist, she exhibited at major venues alongside male colleagues and realized comparable prices for her paintings.

An Artist in the Catskills

Well read, well educated, and well-traveled, Susie Barstow was a notable figure in the field of American landscape painting. She was interviewed often; she published her ideas about the value of experiencing nature directly, and lectured widely on the topic. In her handwritten notes for a lecture on the American landscape, Barstow recalled details from a visit to the Catskill Mountains:

When I was a child I visited the Catskill Mts. As we saw them from the river on a hazy summer afternoon they lay like a delicate cloud – so delicate and dreamlike that it seemed as if a breath would blow them away. I hardly dared to look away from them fearing they might vanish. As we approached, their forms became more distinct but always vapory and unreal, seeming to belong to another world than the river and its wooded shores and villages.

Throughout her extensive career, Barstow commanded the physical landscape of the Hudson Valley, the White Mountains, the rigorous terrain of Yosemite, the Alps—actually, any mountain range she encountered that offered stunning vistas and marvelous views—all the while altering her long skirts and hiking garb so as not to be encumbered on these rugged explorations (fig. 4). Susie Barstow was undaunted.

An Adherent of the Hudson River School

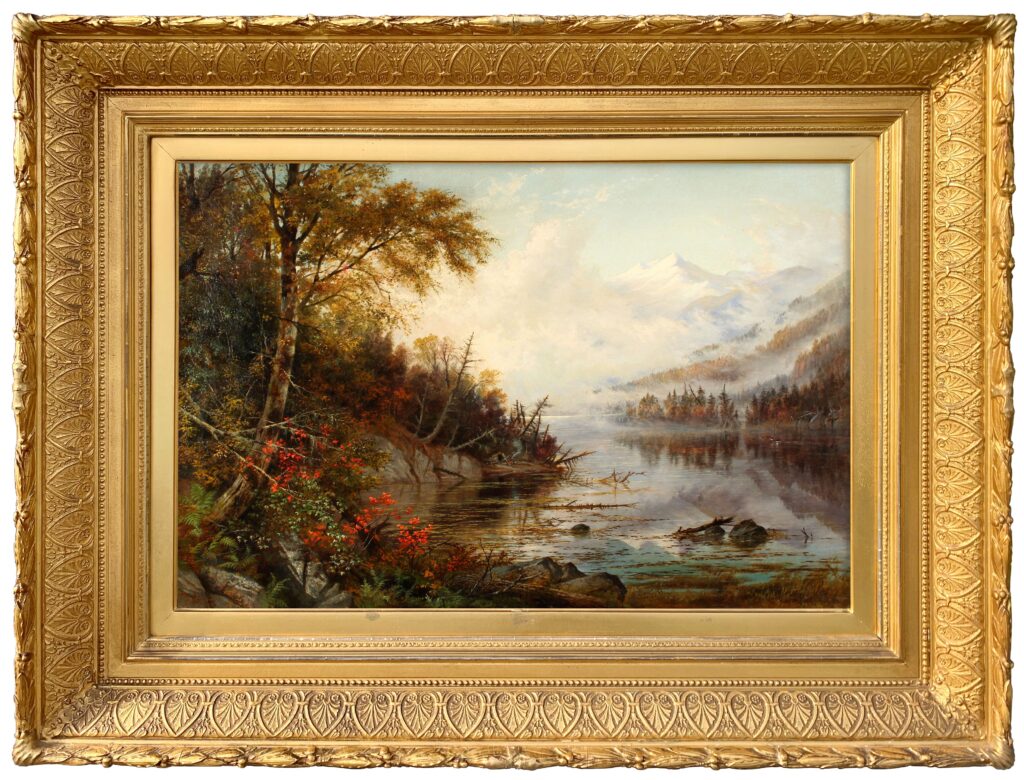

Barstow and fellow artists including Jervis McEntee, Julie Hart Beers, and John William Casilear for example, were part of the second wave of the Hudson River School—an era after the Civil War in which Reconstruction and economic growth fueled the art market, spurring increased demand for smaller, intimate scenes of the American landscape (fig. 5).

Artists such as Barstow responded enthusiastically to this call for parlor-sized compositions from a new and vibrant middle class of collectors who were eager to adorn their walls with scenes of the Catskills and the Green and White Mountains, with their unspoiled rivers, lakes, streams, and wooded scenery—landscape as it still existed, seemingly untouched by progress or war, reflecting a nostalgic taste for a more peaceful past.

In the Prime of Her Career

The prime of Barstow’s career occurred between the 1870s and the end of the nineteenth century (fig. 6), artistically a span of time in which scholars have claimed the Hudson River School had fallen out of fashion, with more avant-garde European influences being favored.

Barstow, however, understood popular taste, and her painterly style evolved continuously across the nineteenth century. While some were purchasing works in the now conservative mode of the Hudson River School, critics and collectors alike were praising an emerging style in which artists reconsidered John Ruskin’s truth to nature philosophies. Channeled through the influence of Barbizon artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny, painters complemented direct observation with sentiment, softer lines, and more diffuse forms. Exploring changes in atmospheric conditions, these French artists produced immersive landscapes, moody and romantic compositions that capitalized on a spiritual communing with nature. Barstow was enormously influenced by their work (fig. 7) and by the paintings of Corot in particular.

She kept newspaper clippings explaining his studio methods in her paint box, which was filled with supplies that included camel-hair brushes, porcelain palettes, watercolors, and white flake pigment (fig. 8).

Evolving Style

Barstow was ever curious to educate herself in both traditional and avant-garde artistic movements while always adhering to her passion for direct observation in nature. This outlook resulted in works that were praised, exhibited, and purchased throughout her extensive career, demonstrating her ability to commingle conservative and progressive styles popular with the American public. Her formal evolution is reflective of an artist who wished to remain relevant in the art world on both the east and west coasts, and her travels took her across the United States to capture the varied terrain.

Travels and explorations

As an artist of determination and determined independence with a passion for exploration, Barstow often left her traveling companions to hike and sketch on her own. She enjoyed continuous bouts of wanderlust, using her Brooklyn home and studio as a place to unpack, paint, visit with family, and entertain friends; she would then take off for new adventures. Whether traveling alone, with friends, or sometimes with her students to places of immense beauty to sketch, it was not uncommon for Barstow to hike 8, 10, or 12 miles, only then to sit down and commence with the task at hand—to capture in detailed studies on paper or canvas the wondrous charm she encountered out of doors, inspired by the natural environment, especially the White Mountains (fig. 9).

Living in Tumultuous Times

Having lived for 87 years, a lifetime spanning two centuries, Susie Barstow witnessed a vast array of political upheaval, scientific advances, cultural events, celebrations, and American progress defined broadly as part of a changing world. As a young woman, she lived through the Civil War and later, the First World War. She benefited from the development of pasteurization and the washing machine, and watched as New York streets converted from the horse and carriage to trolleys and then to the automobile. Born during the infancy of photography, Barstow saw its many technological advances that gave rise to a redefinition of realism—optical, social, and emotional. The photographic exposés of Jacob Riis, for example, were in line with her own commitment to social justice and charitable causes. Barstow’s exhibition history took place on both sides of the East River just as John A. Roebling was spanning the divide between Brooklyn and Manhattan with his Brooklyn Bridge (1869–83), making for easier travel between the two boroughs. Barstow experienced the Age of the Skyscraper—an American architectural invention that rivaled the height of mountaintops, forever changing the skyline of urban landscapes.

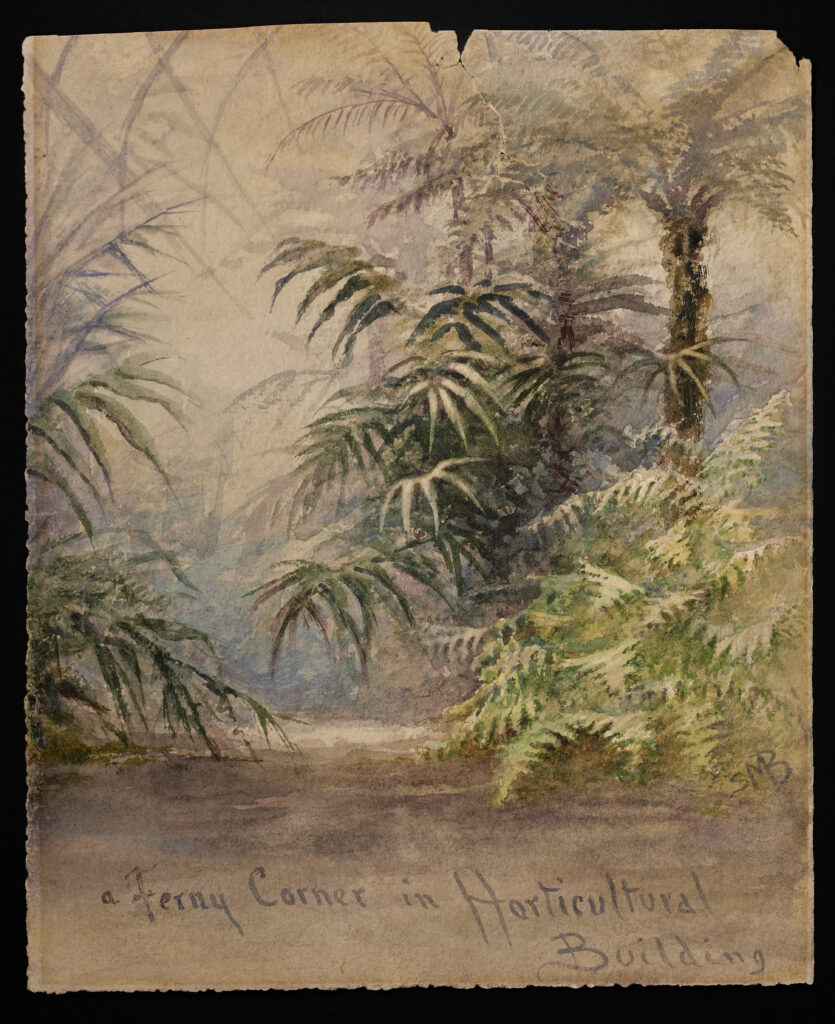

She experienced the shift from the telegraph to the telephone, and Edison’s invention of the phonograph and the electric lightbulb. Barstow attended Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, making watercolor sketches (fig. 10) and saving her entrance tickets as souvenirs. She observed the myriad means by which motion and sound advanced in exciting ways: the roller coaster at Coney Island, the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk in North Carolina in 1903, and talking motion pictures. The Museum of Natural History (1869), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1870), the New York Public Library (1895), and the Brooklyn Museum of Art (1897) were all created during her lifetime. And, of great importance, Barstow lived long enough to celebrate the ratification of the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, which gave women the constitutional right to vote. What an incredible time in which to live and paint!

Conclusion

Susie Barstow was committed to expressing the majesty she found in nature (Fig. 11). In her “dainty little studio,” she captured the larger American landscape experience as it evolved across the nineteenth century.

Landscape paintings of exceptional quality by nineteenth-century women artists such as Barstow are continually coming to light and to market while the work of scholars, gallerists, collectors, and museum professionals moves our knowledge and appreciation forward. Institutions such as the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Albany Institute of History & Art, and the New Britain Museum of American Art, to name just a few of the museums that are actively acquiring and exhibiting works by previously unrepresented women artists, reflect the reprioritizing of paintings, watercolors, and drawings by artists such as Susie Barstow to illuminate an expanded history of the Hudson River School.

Nancy Siegel is Professor of Art History and Culinary History at Towson University; she specializes in American landscape studies, print culture, and culinary history of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This essay is adapted from her book, Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School (read Alexandra Kiely’s review of this book on A Scholarly Skater, and Emily Snow’s review for DailyArt Magazine). Nancy curated Susie Barstow & Her Circle with Kate Menconeri and Amanda Malmstrom, the curators of the Contemporary Practices portion of the current two-part exhibition Women Reframe American Landscape: Susie Barstow & Her Circle / Contemporary Practices (Thomas Cole National Historic Site: May 6–October 29, 2023; New Britain Museum of American Art: November 16–March 30, 2024).

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

The Floral Art of Emily Cole, by Erika Gaffney

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Women Artists from Savannah at the Telfair Academy Museum, by Julie Allen

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Women Reframe American Landscape at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, by Erika Gaffney

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Trackbacks/Pingbacks