Guest post by Alexandra Kiely, independent art historian

The American abstract painter Alma Woodsey Thomas (1891–1978) did not fit well into stereotypes. She was a Black female artist who dedicated much of her life to teaching—in stark contrast to the largely white male egos of art stars in her era. Alma Thomas painted in an optimistic, colorful style seemingly at odds with the racism she likely experienced on a daily basis.

She actively involved herself in Black society and arts in her hometown of Washington DC but was never involved in the civil rights movement. She made a name for herself as a retiree in her 70s and 80s through a surprisingly energetic and even youthful style but was nowhere near as much of a late starter as she’s commonly thought. Her work is beloved for its seeming simplicity, but it was actually the result of meticulous planning and a lifetime of learning and sophistication. It’s no wonder that people seem to have so many different, often contradictory, ideas about her life and work.

Beginnings

Born in Savannah, Georgia, Thomas and her family moved to Washington DC in 1907 to escape then-rampant racial violence in the southern US. She lived in Washington for the rest of her life. Thomas attended Howard University and in 1924 was one the first graduates of its new fine art school. She would remain closely connected to Howard throughout her career.

Then, she became an art teacher at DC’s all-Black Shaw Junior High School, working there until her retirement in 1960. She was also highly active in DC’s Black community through art, theater, religion, and philanthropy. She even served as vice president of Barnett Aden Gallery, the nation’s first Black-owned art gallery, which was founded by two of her former Howard professors. Thomas was clearly a worldly and creative woman. I imagine that her multifarious interests must have made her a particularly wonderful teacher.

Because Thomas’ greatest public and critical acclaim as an artist came in the last few decades of her life, people tend to assume that her artistic career was a second act. The words “late bloomer” come up often in writings about her. However, that’s not really accurate. On the contrary, she was an active artist and student of the arts throughout her life. In fact, she spent time at various universities to further both her art and her teaching. She also studied art history and criticism, color theory, puppetry, and more. She traveled widely, read, visited exhibitions, and actively contributed to Washington’s artistic community, often crossing racial lines in the process. It is true, however, that she landed on her iconic style only after she had retired from teaching and began to devote all her time to her art.

Alma’s Distinctive Style

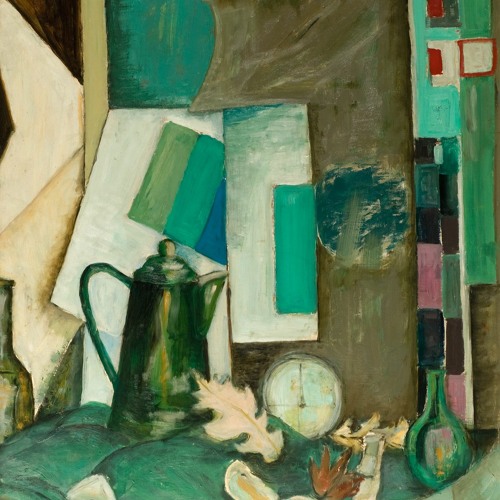

Thomas began as a figurative artist in a broadly Post-Impressionist style. She switched to an Abstract Expressionist mode while studying painting at American University in the 1950s.

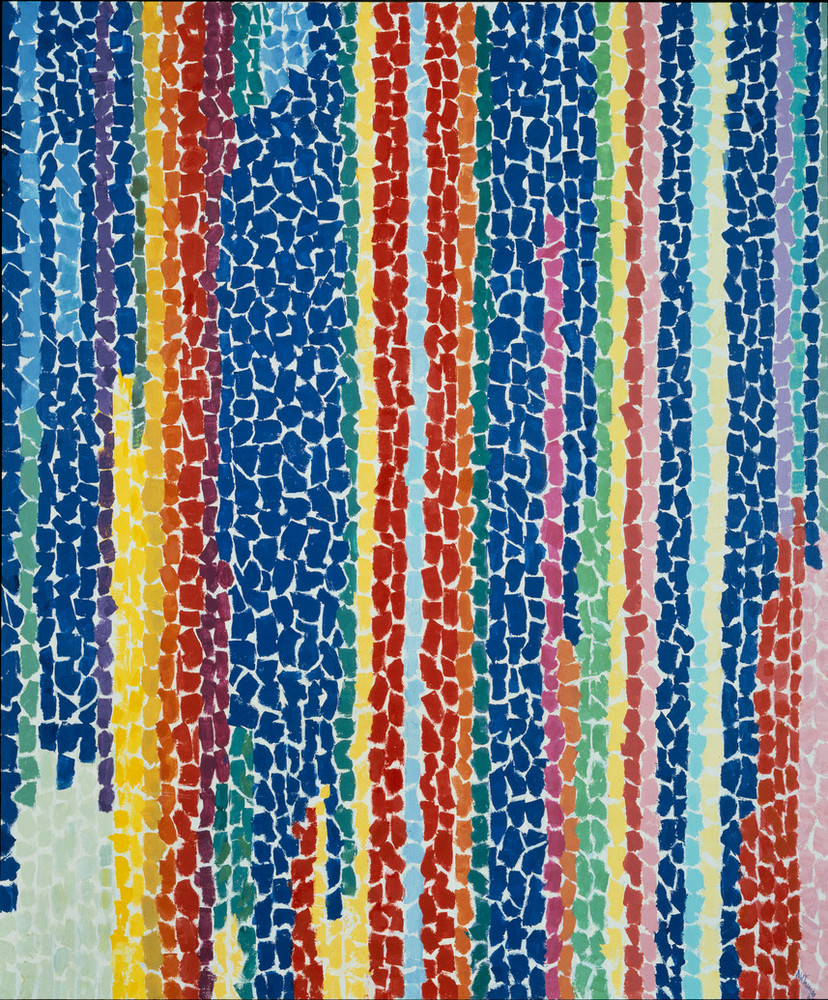

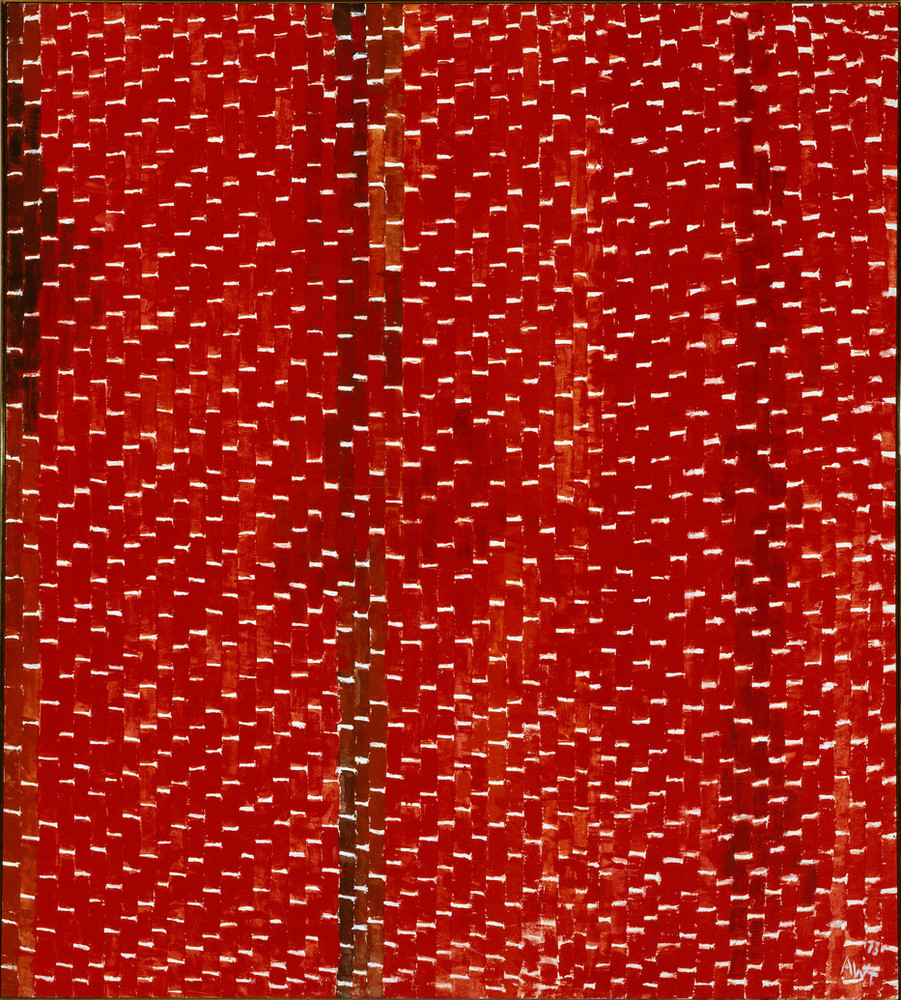

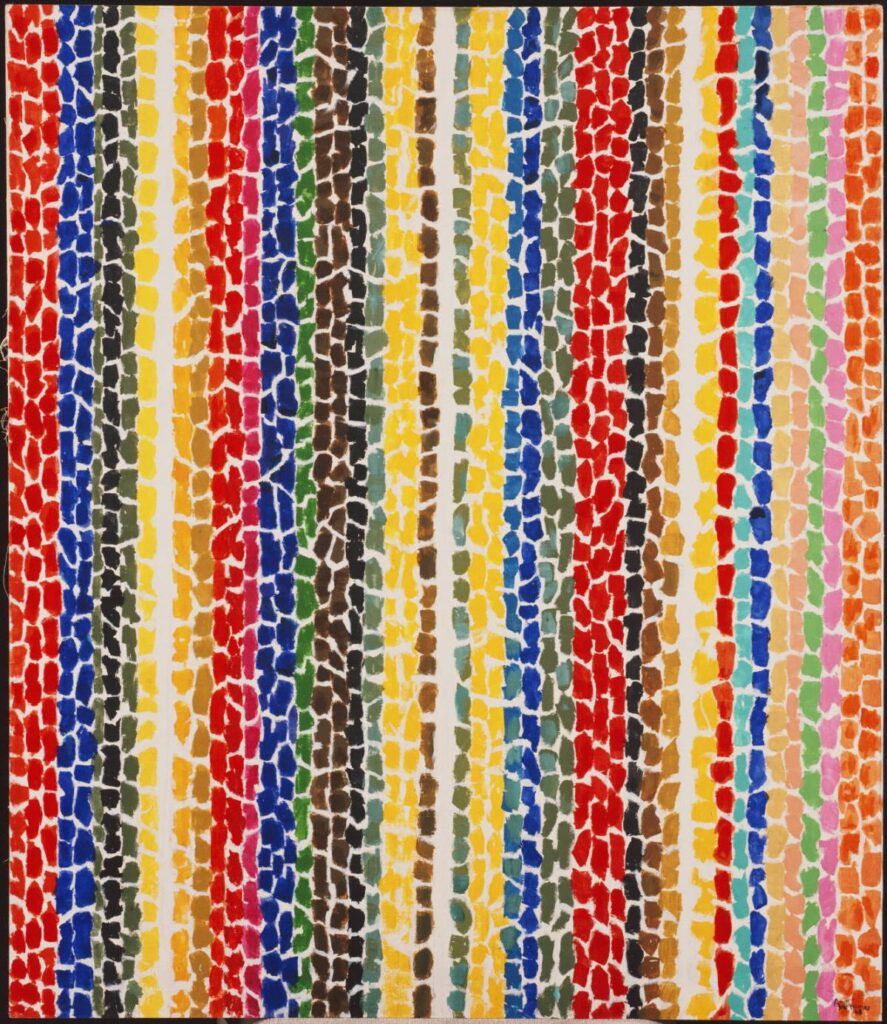

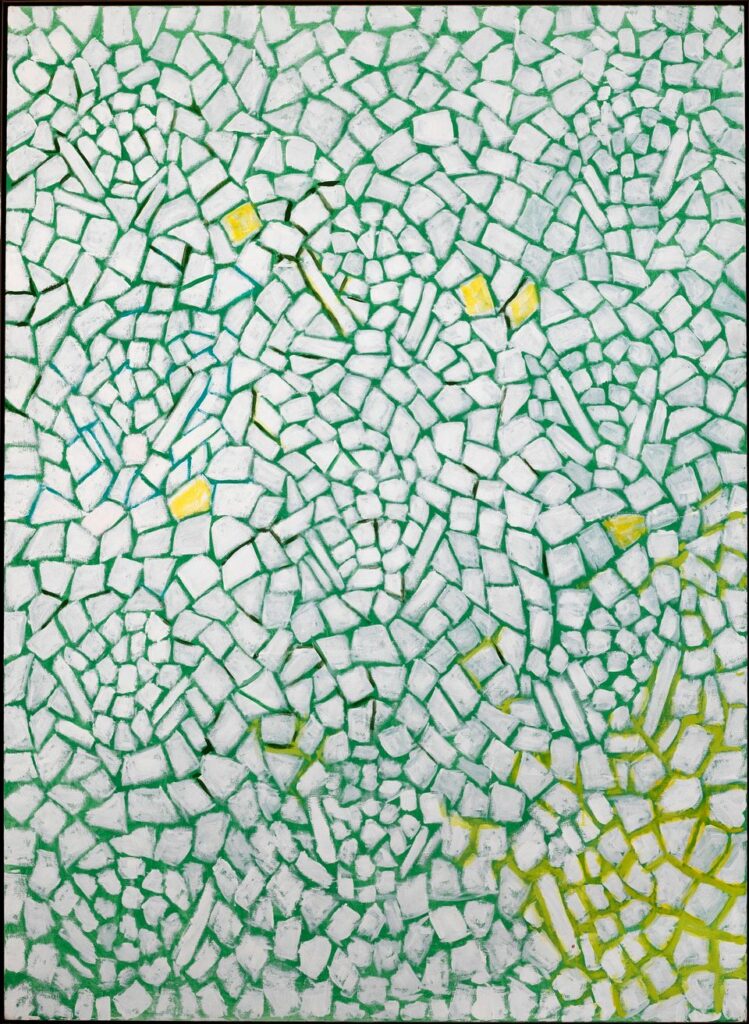

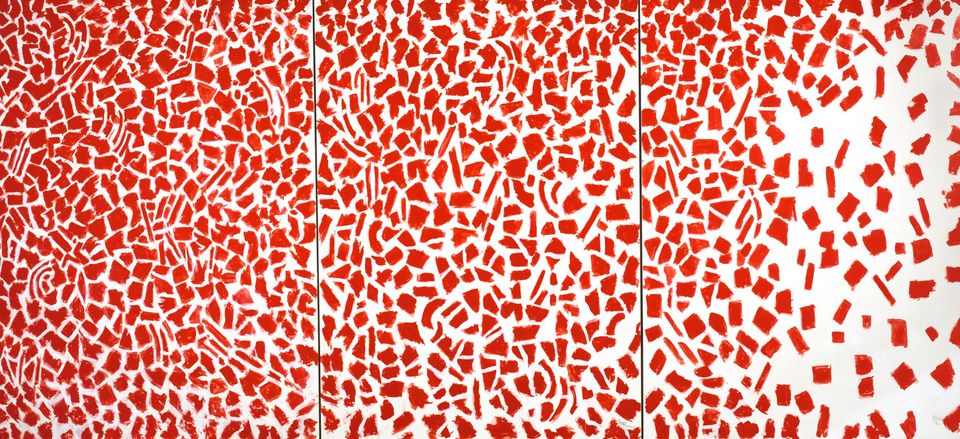

However, it was not until the following decade that she created her iconic style of using short, individual paint strokes sometimes called “Alma’s Stripes.” She first created them while making new paintings for a 1966 solo show at Howard University. She apparently found inspiration in the patchy, dappled pattern of light and color created by her rose bushes outside her window. People often compare the stripes to the tesserae in mosaics. Alma’s Stripes often appear in a rainbow of colors to form parallel lines or concentric circles. Other times, paintings use only two or three colors and feature either parallel or tessellated stripes covering a solid background. Thomas’s new style—impossible to mistake for anyone else’s work—generally fits into the headings of Color Field Painting and the Washington Color School, a DC-based group of mid-century abstract painters.

Although her paintings give the impression of joyful spontaneity, Thomas actually constructed them quite carefully. In fact, old photographs show her taping sheets of paper to her wall to lay out a large composition. Meanwhile, annotated sketches and watercolors demonstrate how she planned her use of color. Also, she habitually made multiple versions of the same composition in order to try slightly different things in each one. Because the aging artist struggled with arthritis and other mobility issues during her most productive years, she needed all sorts of preparation to paint on the large scale she chose to employ.

Inspirations

As we can see through her painting titles, Thomas counted nature, music, and the cosmos (including NASA space flight) as her main artistic subjects. She particularly found inspiration in her own, lovingly cultivated garden and in other landscapes around Washington, as well as in the music she listened to while painting. Given the abstract nature of her art, however, the relationship between her subject matter and her compositions was not literal or direct.

One thing that doesn’t seem to have motivated her art was politics, racial or otherwise. In fact, Thomas was very clear about not wanting to bring these topics into her work. Conveying beauty and joy was her aim instead. She said:

“I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No, I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at.” (Quoted in Feman, Seth and Jonathan Frederick Walz, “‘Then the Light Would Come Around’: An Introduction” in Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021 P. 24.)

Obviously, we shouldn’t take this to mean that she did not experience racism or care about the Black community, just that the focus of her art was elsewhere. We also know she preferred her work to stand on its own without labels like “female artist” or “Black artist.”

All that said, it’s really easy to read Thomas’s bright, cheerful paintings as deliberate antidotes to hardship and suffering. Some have even seen her space-themed paintings, in particular, as part of Afro-Futurism through their deliberate manifestations of Black liberation in space. Despite much speculation about Thomas’s complicated relationships to race, gender, and age, we’ll likely never have clear answers. She was surprisingly quiet on the subject in her words and actions as well as her art.

Acclaim

Thanks to the appeal of Alma’s Stripes, Thomas enjoyed some pretty serious late-career attention, mainly from prominent Washington venues. It all culminated in a 1972 solo show at the Whitney Museum in New York, which made her the first Black woman and fifth Black artist overall to receive an exhibition there. However, the show also proved controversial because of its small size and inopportune placement. Some critics found it too much of a token gesture at a time when many were protesting the exclusion of Black artists from major museums.

Despite this New York appearance, Thomas has remained most popular in Washington. In the nation’s capital, the Smithsonian American Art Museum owns the world’s largest collection of her work, including pieces she donated herself.

Fellow Washington institutions like the National Gallery of Art, Phillips Collection, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and National Museum of Women in the Arts own numerous Thomas paintings as well, while the Archives of American Art contains her papers. Thus, it is particularly fitting that the Obamas added two of her paintings to the White House Collection, making her the first Black female artist to be included. Resurrection even hung on the wall in the White House’s Family Dining Room following the room’s renovation.

This well-publicized acquisition triggered a burst of renewed interest in her work and several major exhibitions. Most recently, the multi-venue 2021–22 exhibition Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful fully re-evaluated her life and career, and thus both the accompanying catalog and associated online resources were major sources for this article. Presently, the Smithsonian American Art Museum is hosting the exhibition Composing Color: Paintings by Alma Thomas, which runs through June 2, 2024.

Alexandra Kiely is an independent art historian based in the greater New York area. On her website, A Scholarly Skater, her posts and courses aim to encourage art appreciation in a wider public. Her work has also appeared on websites like DailyArt Magazine and The Collector. Alexandra has particular interest in 19th-century American painting and medieval European art and architecture. You can also follow her on Facebook and Instagram.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Reflections on the Audacious Art Activist and Trailblazer Augusta Savage, by Sandy Rattler

Science, Nature, and Music in the Art of Alma Thomas, by Erika Gaffney

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Nancy Sharp: An Undeservedly Forgotten Exemplar of Modern British Painting, by Christopher Fauske

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs