Guest post by Thomas Cooper, University of Cambridge

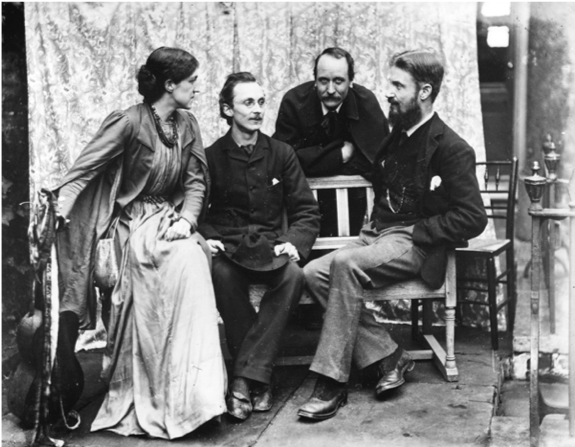

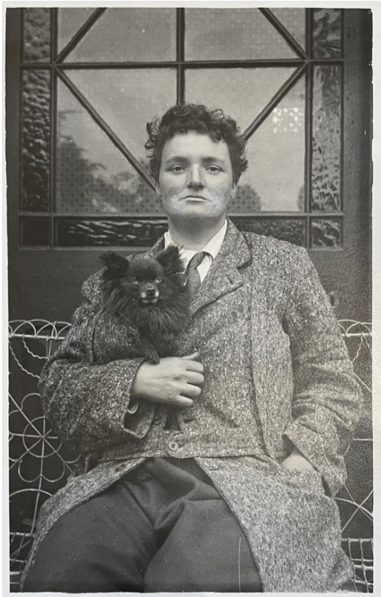

On this day, one hundred years ago in 1923, the Arts and Crafts luminary May Morris (1862–1938; Figure 1) turned sixty-one years of age. The year marked a turning point in her long and creative life. She left her rented riverside townhouse in Hammersmith, London, and moved permanently to Kelmscott Manor. This was a large, seventeenth-century stone manor house in rural Oxfordshire, which her family had rented since 1871 and owned since 1913 (Figure 2). The move to the countryside, however, was no step into idle retirement. In fact, it was the start of an adventurous new chapter in Morris’s life.

But who was Morris? In this short blog post, I want to give some more depth to Morris’s rich and complex character.

Who was May Morris?

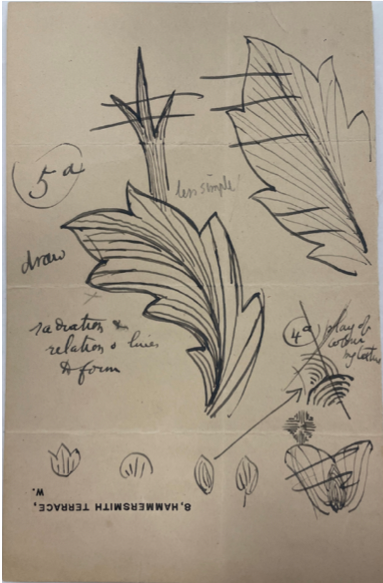

Born in 1862 to Jane and William Morris of Pre-Raphaelite and Arts and Crafts fame, she was a leading figure among the second generation of the Arts and Crafts movement. After training at the National Art Training School (now Royal College of Art), she began her career in the early 1880s. Financially supported by her family’s prosperous interior decorating firm, Morris & Co., she lectured on historical textiles, privately taught embroidery at home, and, from 1885 to 1896, successfully managed the embroidery workshop of the family business (Figure 3).

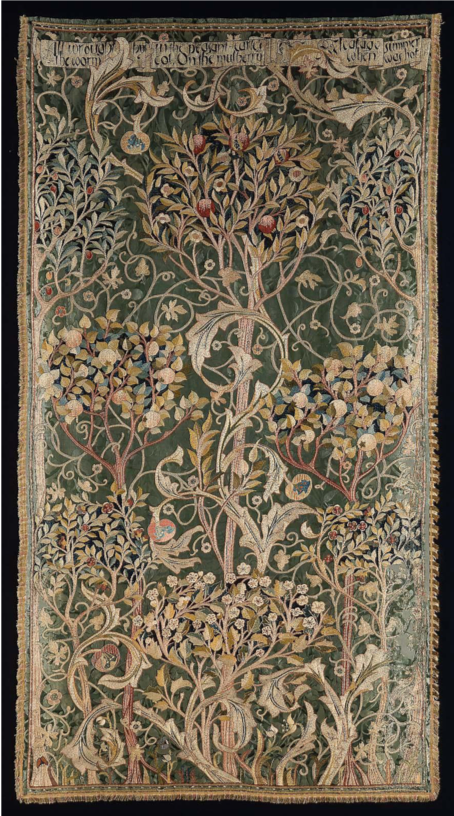

Recent exhibitions and publications have brought the career and work of May Morris to a wider audience. Morris has been recognized as a celebrated embroiderer and influential voice in the lasting legacies of the Arts and Crafts movement. She produced some of the finest embroideries of the late nineteenth century (Figure 4). Among her many noted accomplishments, she co-founded the Women’s Guild of Arts in 1907. This organisation supported women art and craft workers in the twentieth century. It was a key forum for women’s collaboration in the Arts and Crafts.

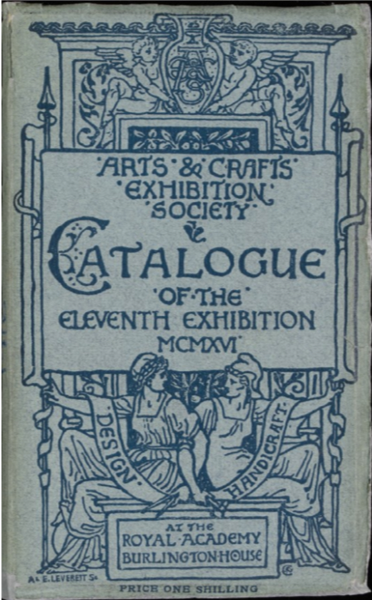

Over the next forty-or-so years, Morris led an esteemed career as a prominent designer and textile maker. She regularly exhibited at major arts and crafts exhibitions (Figure 5).

She taught at leading schools of art and design and lectured across Britain and the United States of America (Figure 6). She also became a noted scholar on historical textiles.

Morris’s Relationships

By 1923, Morris had married and divorced Henry Halliday Sparling and reconciled her unrequited romantic affections for George Bernard Shaw and John Quinn (Figure 7).

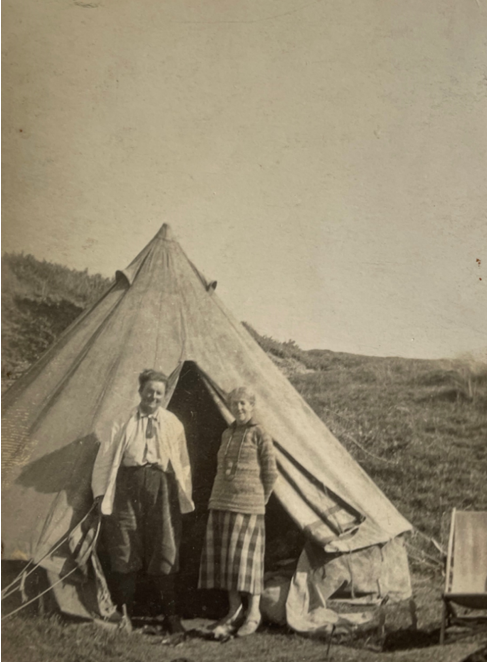

Some regard this record as a series of failed relationships and, in turn, see Morris as unlucky in love. However, by this date, she had begun a relationship with a woman, Mary Lobb (1878–1939, Figure 8). This proved to be Morris’s most significant non-familial relationship.

Hailing from Cornwall, Lobb had background in gardening, agriculture and machinery. In 1917, she arrived in the village of Kelmscott as part of the Women’s Land Army movement. Initially, she worked on a local farm and lodged with the village blacksmith. After an altercation with the blacksmith, she moved into Kelmscott Manor and worked there as a gardener.

Morris and Lobb lived together for over twenty years. Their relationship grew into intimate, loving and caring life-partnership. They shared passions together; provided for one another humor and companionship; and supported each another through family difficulties, emotional tribulations, and illness. Lobb, practical, forthright and no nonsense in nature, was an emotional cornerstone for Morris. She described Lobb as “so capable and so encouraging and patient, and so apt to deal with everything that comes along to worry one.” In 1933, Morris wrote: “I should be lost without her.”

Experiencing Nature

They were an intrepid couple. Travelling by rail, car, boat and food, they explored the coasts, valleys and mountains of Wales and Northumberland, the moorlands of Devon and Cornwall, and the islands of Scilly and the Outer Hebrides (Figure 9). They sought out pre-historic sites, followed rivers in search of their sources, and enjoyed local delicacies.

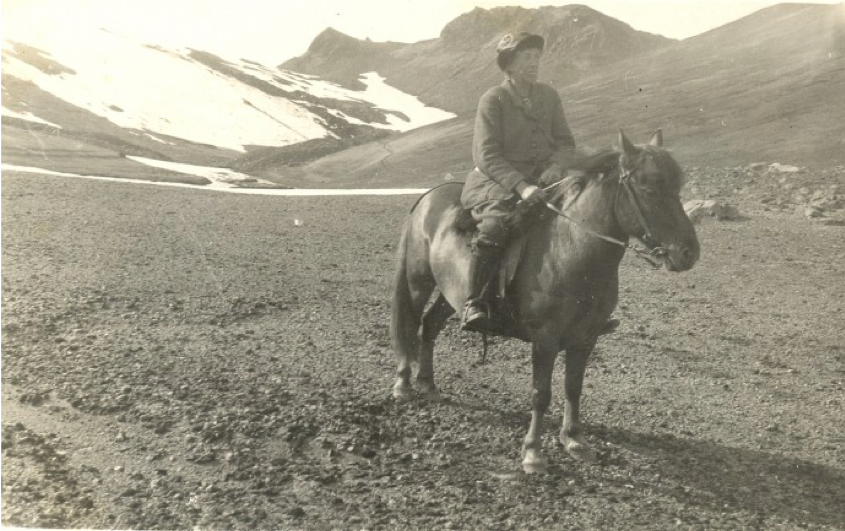

Their most adventurous travels were to Iceland. They made three trips to Iceland, in 1924, 1926 and 1931. Morris was overwhelmed by the beauty of country’s landscapes, which they explored extensively on horseback and by car. A keen amateur photographer, Lobb captured their adventurous spirit as they cross mountains and explored ravines (Figure 10).

Morris delighted in nature. She reached for jewel metaphors to describe dazzling seascapes and landscapes. Elemental forces and geological formations thrilled her. She watched with pleasure the swifts, jackdaws and kingfishers that darted and hovered around Kelmscott. She was especially fond of birds. They wheel and dive across the pages of her sketches and designs; in her embroideries, she stitched wing and tail feathers in kaleidoscopic wool and silk threads (Figure 11). Morris and Lobb enjoyed a small menagerie of animals at Kelmscott, which included a dog, cats, horses and goats.

At home, Morris’s daily pleasures were found in picking flowers, writing in the garden, taking bicycle rides, smoking, reading aloud detective stores after dinner, and poring over travel literature while tucked up in bed. Her reading and academic interests were varied, covering British geology, Gaelic folk songs, Chinese painting, Arabian poetry, and expeditions in the Middle East.

“Fire and Ice”

Bernard Shaw described Morris’s personality as being like “fire and ice.” This is an oversimplification, but these two qualities were certainly aspects of her character. She was generous, affable, and good-humored. She revelled in a good joke. Morris responded with great feeling to artworks, buildings and landscapes. She passionately championed the vital role of art making in a fulfilling life. And she earnestly supported collaboration and community among artworkers. But ice could swiftly form. She was direct, pedantic, and quick tempered; she liberally voiced her disapproval; and her artistic criticism could be blistering. Intelligent, critical, talented, self-effacing, curious, kind, hot-headed, principled, Morris’s character was rich and complex.

Thomas Cooper is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge. His doctoral research examines the career and work of May Morris, with a focus on her textiles, designs, making practices, and writings. He completed his BA (Hons) and MA degrees at The Courtauld Institute of Art, graduating with the Director’s Prize for Outstanding MA History of Art Dissertation. His doctoral research is funded by the University of Cambridge Pigott Studentship, and his research has been supported by Kettle’s Yard, the Paul Mellon Centre, and the William Morris Society in the United States. Follow Thomas on Twitter!

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney

A Room of Their Own: Now You See Us Exhibition at Tate Britain, by Kathryn Waters

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

Defining Moments: Mary Cassatt and Helen McNicoll in 1913, by Julie Nash

Laura Seymour Hasbrouck, A Painter of the Hudson River School, by Lili Ott

Susie M. Barstow: Redefining the Hudson River School, by Nancy Siegel

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Piola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

Celebrating Eliza Pratt Greatorex, an Irish-American Artist, by Katherine Manthorne

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

Happy Birthday, Fidelia Bridges! by Katherine Manthorne

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

Esther Pressoir: Imagining the Modern Woman, by Suzanne Scanlan

Dear Mr. Cooper,

Thank you for this illuminating article. I am researching a friend of May Morris called Evelyn Gleeson. I wondered if you have come across Evelyn in your research.

If so,please let me know. Thanks and please keep writing.

I would like to live full time in 1880’s London! Best wishes,Kathleen Scullion