Guest post by Rebekah Hoke Brown, Indiana University Bloomington

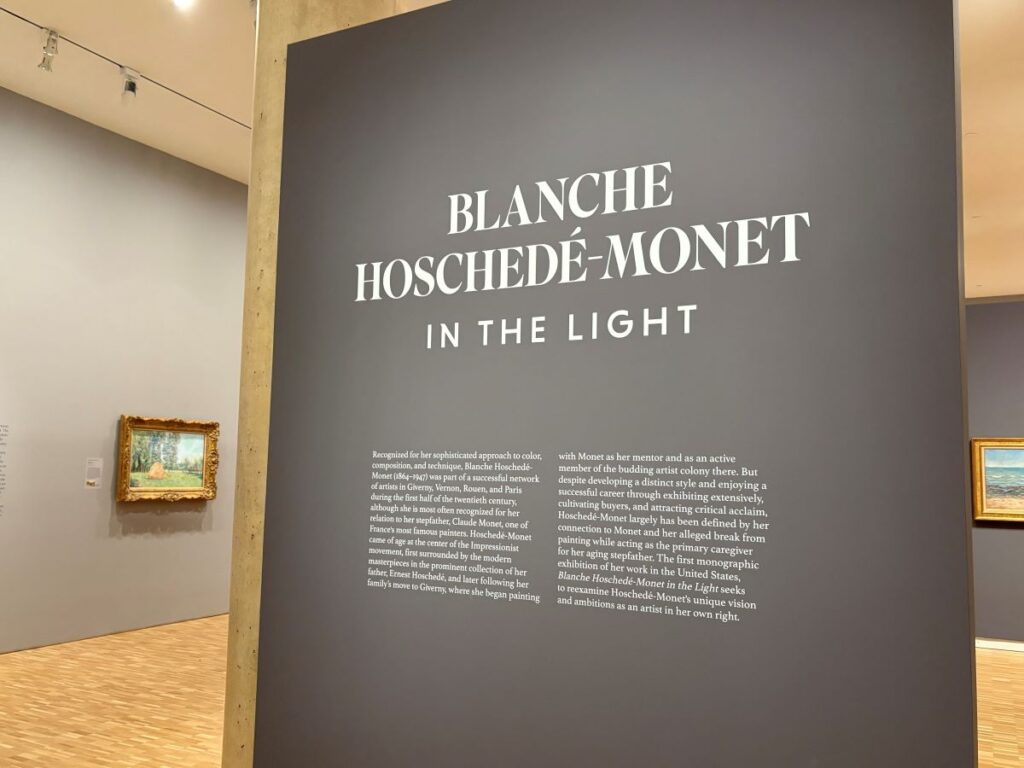

This February, the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana opened a new exhibition entitled Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light. It is the first monographic exhibition of the work of Blanche Hoschedé-Monet (1865–1947) in the United States. Though Hoschedé-Monet is often associated with her stepfather and mentor, the Impressionist Claude Monet, this exhibition emphasizes Hoschedé-Monet’s contributions to the Impressionist movement and highlights her unique identity as an artist.

The exhibition brings together thirty-eight artworks arranged chronologically, spanning Hoschedé-Monet’s career. Beginning with her early days accompanying Monet to study the cliffs of Pourville and the vistas of Giverny (1882–1897), the exhibition gives pictorial form to Hoschedé-Monet’s journey: the development of her own career as an artist in Rouen and Beaumont-le-Roger (1897–1913), her return to Giverny and disputed artistic hiatus to care for an aging Claude Monet (1913–1926), and a fruitful period of travel and artistic freedom in the last decades of her life (1927–1947).

Setting the Tone

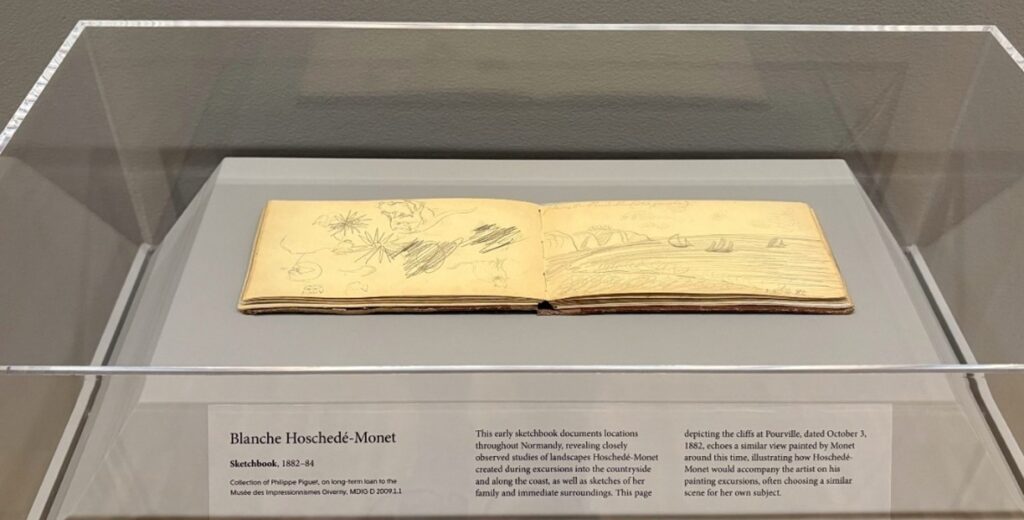

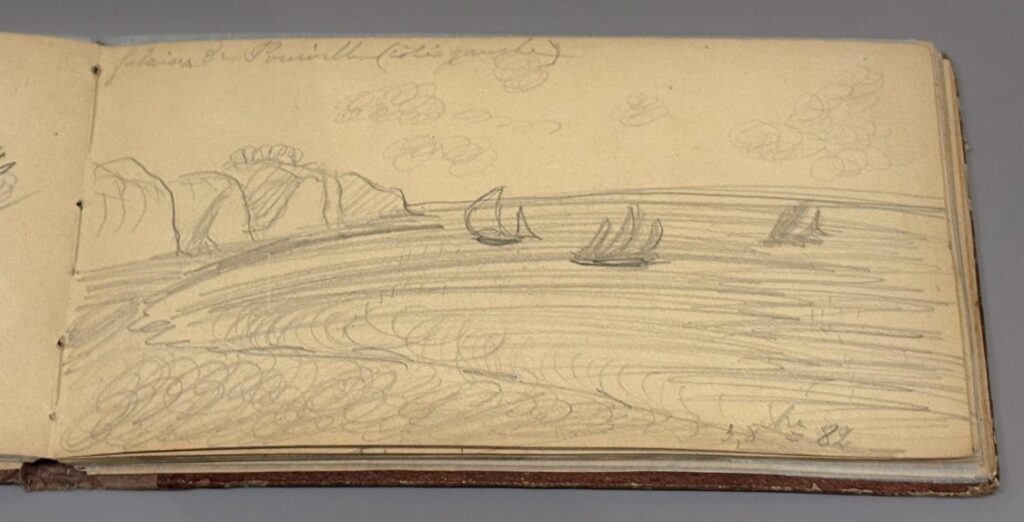

Directly to the left of the gallery entrance, two objects begin the exhibition program. The first is Hoschedé-Monet’s sketchbook, dated 1882–1884. The other is the painting Cliff Walk at Pourville by Claude Monet (1882). It is initially surprising to see that the first oil on canvas work of the exhibition is by Claude Monet, instead of the artist for whom the exhibition is named. However, the juxtaposition of the sketchbook with this work sets an interesting contrast for visitors to consider as they examine the rest of the space. Upon closer inspection, Monet positions Hoschedé-Monet as a subject; whereas, in her own sketchbook, she is an autonomous artist.

Negotiating Ties

In Monet’s artwork, Hoschedé-Monet and her sister Martha are depicted at the precipice of a Pourville bluff. With their parasols, the two sisters are expressed in Monet’s characteristically windswept and instantaneous style. Cliff Walk is one of many Monet works in which the Hoschedé-Monet sisters play a part. Monet’s Rowing Boat series (c.1887–1890) is another such example.

However, Hoschedé-Monet’s sketchbook, which viewers can examine up-close, reveals her own careful studies and observations of the Pourville area. These sketches reveal that she investigated the landscape with her own meticulous artistic eye. While Monet introduced her to the Impressionist style and she often paralleled his painting excursions as a teenager and young adult, Hoschedé-Monet had a unique vision and ambitions of her own. By juxtaposing Claude Monet’s work, in which Hoschedé-Monet is a part of the landscape, with Hoschedé-Monet’s sketchbook and a gallery full of her own artwork, this exhibition frames Hoschedé-Monet as not simply a subject within Monet’s art and a character in his story, but as an artist “in her own right.”

“In the Light” of Claude Monet

As a result, the exhibition strikes a balance in its artwork and wall texts. They do not shy away from Hoschedé-Monet’s personal connection and occasional similarity in subject matter and style to Claude Monet. The two artists are key members in each other’s story. But instead of overly emphasizing Hoschedé-Monet’s connection to Monet, this exhibition focuses on her unique artistic practice and difference in perspective, touch, and experience. The works reveal crucial moments in Hoschedé-Monet’s career where she diverged from Monet’s oeuvre, creating for herself new spaces to exhibit her work, new artistic networks, and new patrons. As Jean-Pierre Hoschedé, her brother and biographer, aptly stated and is echoed in the exhibition title, she “was not in the shadow, but in the light of Claude Monet.” By bringing Blanche Hoschedé-Monet “into the light,” this exhibition restores her to her proper place within art history.

Rick Johnson. Author photo.

Her Own Artistic Vision

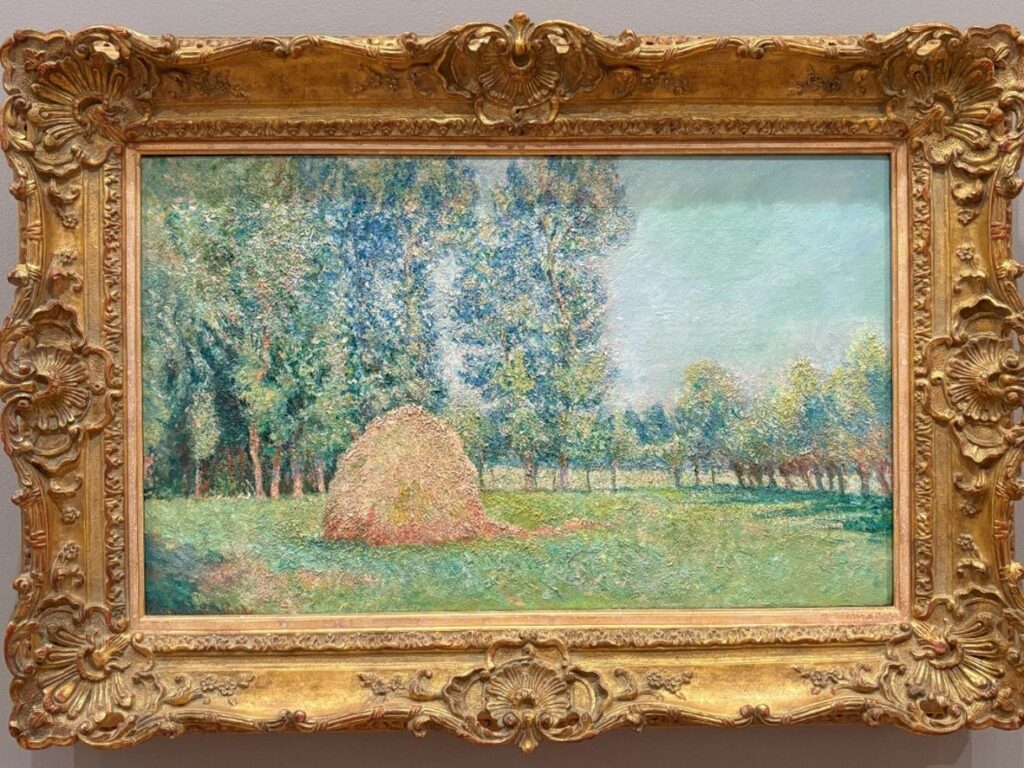

One fantastic example in the gallery is the inclusion of Haystack at Giverny (1893). While Hoschedé-Monet’s work shares the setting of Monet’s haystacks, her method and compositional choices are unique. Instead of depicting the haystack at the center of the canvas like her mentor Monet, the wall text reveals that Hoschedé-Monet chose to move her easel and approach the scene from a different vantage point. Hoschedé-Monet offsets the solitary haystack against the dense line of trees in the background.

This consciously simple arrangement of the scene decenters the haystack, achieving balance by contrasting the monumentality of the haystack with the open blue sky above and trees in the background. Upon closer inspection of the work in person, Hoschedé-Monet’s brushstrokes also capture this contrast. Her quick brushstrokes highlight the instantaneity of the moving clouds in the sky and the wind blowing through the trees. And her heavy impasto (or thick, textured layering of paint) highlights the solidity of the haystack itself. While Hoschedé-Monet was inspired by a similar scene as her stepfather, it was her own artistic insights that guided the composition.

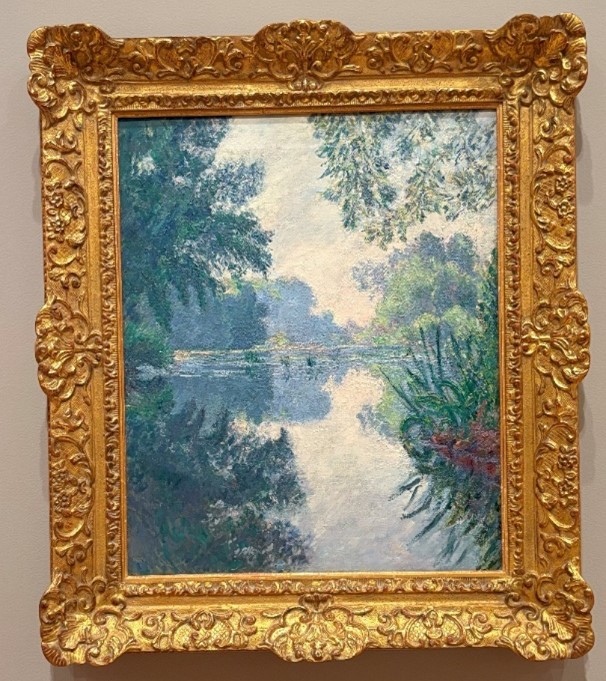

Similarly, Hoschedé-Monet’s own artistic instincts are evident in another work on display in the exhibition: Morning on the Seine (c. 1896). Though Monet is also well known for his Morning on the Seine series, Hoschedé-Monet painted the same view at his side. Once again, Hoschedé-Monet’s approach to the scene reveals her commitment to compositional balance in her use of framing devices and reflections. The exhibition makes it clear: during these formative years learning side-by-side with Monet, Hoschedé-Monet did not imitate but made her own artistic choices.

Independence in Rouen

The exhibition celebrates an important shift in Hoschedé-Monet’s life towards artistic independence. After marrying Monet’s son, Jean Monet, in 1897, the newlyweds moved to Rouen. Her first time away from her family, Hoschedé-Monet’s time in Rouen allowed her space to explore her artistic identity and ambition. She did so both in the 1905 Salon des Indépendants in Paris and within the community of professional artists at the first Salon de la Société des Artistes Rouennais in 1907.

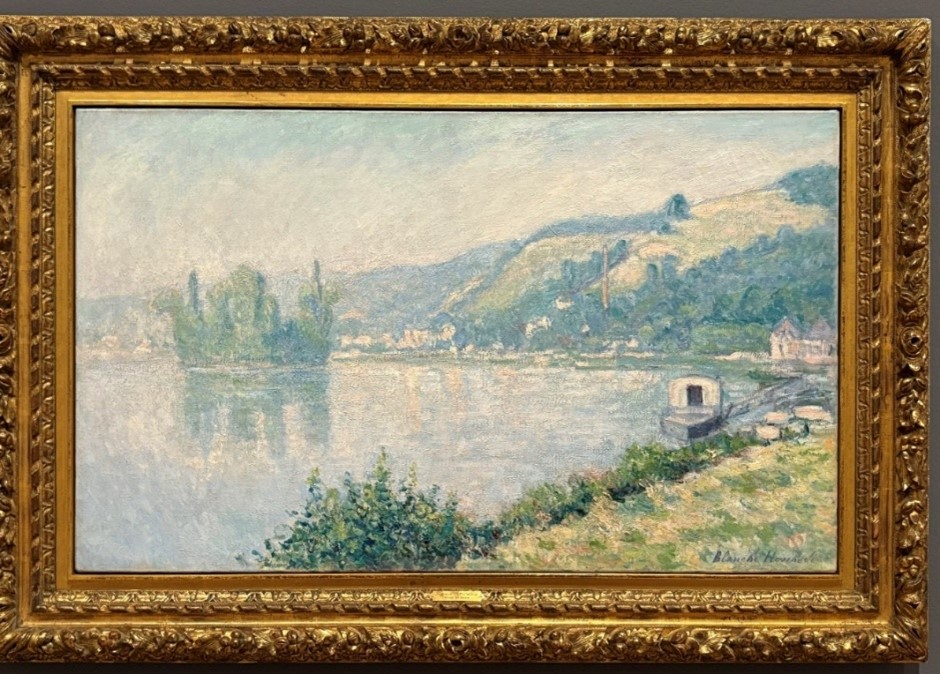

In Rouen, Hoschedé-Monet began to investigate modern life and industry, a topic explored by her peers. In View of Rouen (1900), she captures a precarious intersection between nature, industry, and tradition. At that time, Hoschedé-Monet also began to experiment with creating artwork in series. She produced multiple canvases of the same landscape but with varied color, brushwork, and use of light like in The Bank of the Seine (1897–1910). Hoschedé-Monet, much like others of her time, reacted to the quickening pace of the modern world. Through her artwork, she chronicled each subtle change in the landscape.

Giverny Hiatus

In 1914, Hoschedé-Monet returned to Monet’s Giverny to care for the now seventy-four-year-old Monet. They had both been recently widowed and Hoschedé-Monet reputedly paused her artistic practice to become Monet’s caretaker. However, the exhibition acknowledges that Hoschedé-Monet may have continued painting, as she held a solo exhibition less than a year after Monet’s passing in 1927. During her twelve years with Monet at the end of his life, Hoschedé-Monet assisted him in his Grande Décoration project, creating large scale water lily artworks. After Monet’s death in 1926, Hoschedé-Monet continued to facilitate Monet’s Water Lilies installation at the Musée de l’Orangerie outside of Paris. The exhibition acknowledges Hoschedé-Monet’s significant role in ensuring the legacy of Monet, his artworks, and his beloved Giverny home. During this time shortly after Monet’s death, Hoschedé-Monet’s works reflect the time she spent in the gardens of Giverny, pictorially preserving its memory.

Travel after 1927

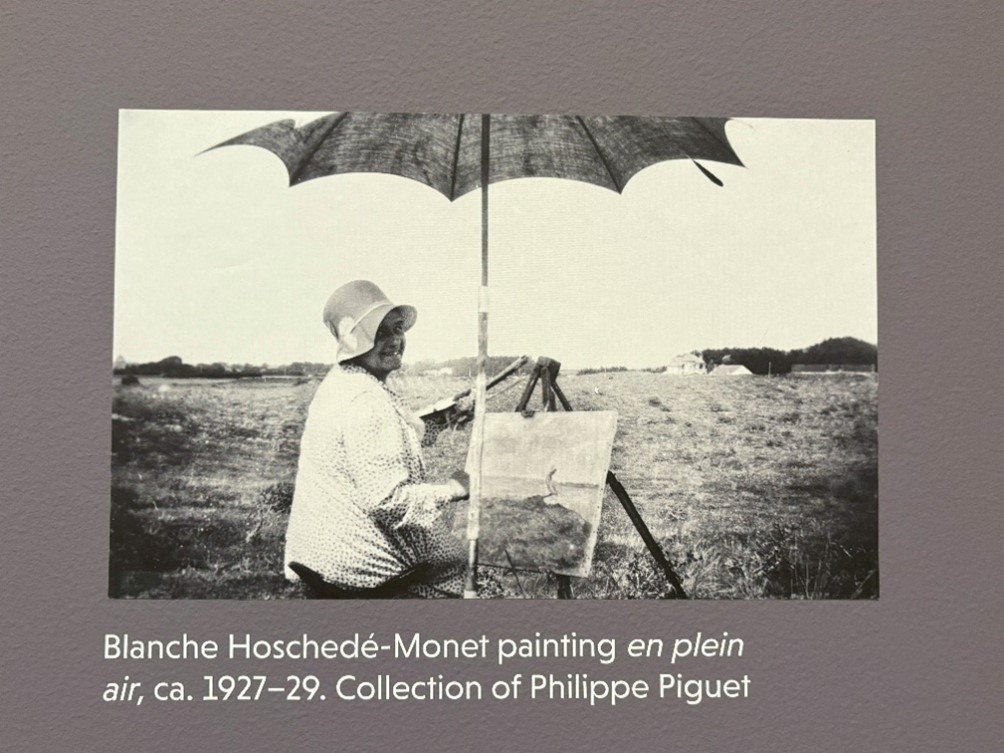

The exhibition notes an important chapter in Hoschedé-Monet’s career after Monet’s passing. Now in her sixties, Hoschedé-Monet travelled all over France to paint en plein air (in the open air/outside). She was drawn to scenes of the ocean and achieved subtle variations of sky, sand, and sea in her depictions.

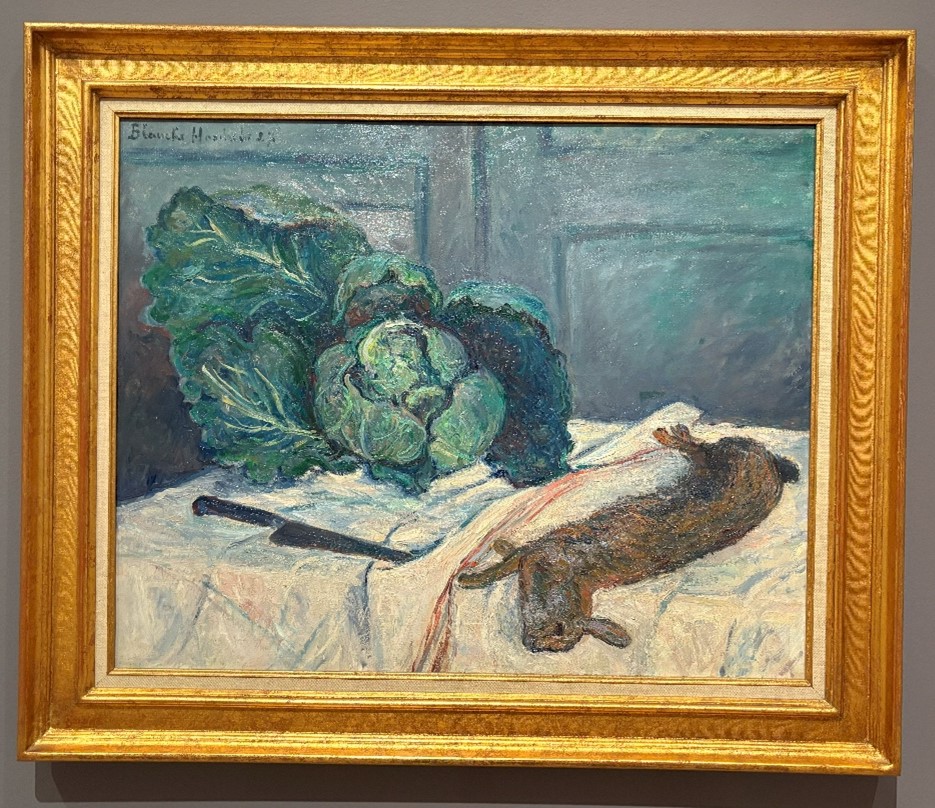

However, in a unique departure from Hoschedé-Monet’s beach motifs of this period, Still Life with Cabbage and Rabbit (1927) reveals the variety in Hoschedé-Monet’s artistic interest. This foreboding scene contrasts lively green brushstrokes on the cabbage surface with the stillness of the hare lying next to a knife.

Exhibition curator Haley Pierce notes that that this work is one of several examples within Hoschedé-Monet’s oeuvre that suggest she was aware of and incorporated elements of the many emerging artistic styles throughout the course of her career. For example, in this work, Hoschedé-Monet alludes to similar post-Impressionist still life scenes by artists like Paul Cezanne and Paul Gauguin.

Life in Bloom

A special section, marking the end of the exhibition, is dedicated to the many floral motifs Hoschedé-Monet painted throughout her life. Beginning with her first known artwork—which she created at only thirteen years of age—and concluding with a depiction of the water lilies at Giverny one year prior to her death, this section reflects Hoschedé-Monet’s ability not only to seek out balance in landscapes, but in close studies as well.

Hoschedé-Monet’s Legacy as a Female Artist

While the exhibition centralizes Hoschedé-Monet’s career and her place within art history, the exhibition catalogue seeks to locate Hoschedé-Monet’s place as a female artist. Art historian Nancy Mowll Mathews notes that Hoschedé-Monet came of age during a period in which women artists began to be acknowledged for their skill in worlds’ fairs, salons, art schools, and in attracting their own patrons. Hoschedé-Monet was ambitious, and the French art world rose to meet her.

But much like Artemesia Gentileschi, Angelica Kauffmann, Lee Krasner, and other female artists throughout the canon, Blanche Hoschedé-Monet is excluded from most art historical narratives. If she’s mentioned at all, the chronicler describes her in relation to male counterparts/family members, or the male-centered stylistic movement with which she aligned. The exhibition grapples with age-old questions: how can contemporary art historians and museum professionals tackle the gender disparities of the art historical past and present? How can they most effectively advocate for greater representation of female artists in the canon and in the museum space?

The Value of Visibility

Despite these challenges, the exhibition does not shy away from its potential as a space to remediate gendered notions of value within art history. Located in a university museum, this exhibition is available to an audience of many different backgrounds. While I was in the exhibition one afternoon, an undergraduate language class entered the gallery, and each student presented an artwork of their choice in Spanish to their peers. The instructor later explained that having the exhibition nearby allowed her students to apply newly learned terms of art and culture to the real world.

There is value in exhibitions like this as points of introduction to art history, even to those whose initial visit is not self-directed. Perhaps after seeing the exhibition in their class, students might remember Hoschedé-Monet, as opposed to her male counterparts, when they encounter Impressionism in the future.

Correcting the Archive

The show is an important entry-point for US scholars as well. In a conversation with curator Galina Olmsted, she noted that Hoschedé-Monet’s scholarly exclusion in large part has to do with lack of access. There are hardly any works by Hoschedé-Monet in US institutions and only a small number on display in French institutions. This exhibition allows researchers the ability to view, study, and read about her work in English for the first time.

In Her Own Right

This exhibition is a thoughtful introduction of Blanche Hoschedé-Monet’s body of work to US audiences. In a sizeable selection of works, visitors can see the countryside of France through her eyes and through each deliberate brushstroke. Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light marks a hopeful shift in the study of Impressionism, establishing Hoschedé-Monet as a significant member of the movement. It also recognizes her as a protégée and protector of Claude Monet’s legacy, and as a unique artist worthy of careful study in her own right.

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light is on at the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University through June 15, 2025.

Rebekah Hoke Brown is an Art History PhD student at Indiana University Bloomington. She specializes in nineteenth-century American and European/Scandinavian art history, specifically trends of transatlantic artistic exchange among artists and patrons. Prior to her time at IU, Brown received her bachelor’s degree in art history from Brigham Young University with a minor in Scandinavian Studies and her master’s degree in art history from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Rebekah’s master’s thesis examined the industrialists and collectors of Gilded Age St. Louis, Missouri, and their portraits by the Swedish artist Anders Zorn. Brown has worked in several museums in Texas, Utah, Denmark, and most recently at Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska.

A heartfelt thank you to Galina Olmsted and Haley Pierce for their insight and collaboration on this article.

More Art Herstory blog posts about French women artists

Unpacking the Exhibition: Blanche Hoschedé-Monet in the Light, by Haley S. Pierce

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Louise Moillon: A pioneering painter of still life, by Lesley Stevenson

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and the Ribbon as a Signifier of a “Woman’s Touch,” by Tori Champion

The Abstract-Impressionism of Berthe Morisot and Joan Mitchell, by Paula Butterfield

Marie Laurencin and the Autonomy of Self-Representation, by Mary Creed

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Victorine Meurent, More than a Model, by Drēma Drudge

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews

Modern Women Artists in Copenhagen 2024–2025: Three Exhibitions, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien van der Pol

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Frida: Beyond the Myth at the Dallas Museum of Art, by Olivia Turner

Women Artists at the Cape Ann Museum, by Erika Gaffney

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840: “The Elisabetta Sirani of the Day,” by Alessandra Masu