Guest post by Tori Champion, University of St. Andrews

An Artist-Naturalist in Paris

The Enlightenment-era painter and draughtswoman Madeleine Françoise Basseporte, though she left little behind by way of letters or written records, lived and worked at the very heart of the French intellectual community in the mid-eighteenth century.

This month, Basseporte celebrates her 321st birthday. She was born on the 28th of April, 1701 in Paris, the city in which she spent virtually her entire life. However, her position as the royally-appointed official plant painter in the King’s Garden not only placed her work on an international stage, but gained her access to materials brought back from the global travels of scientists.

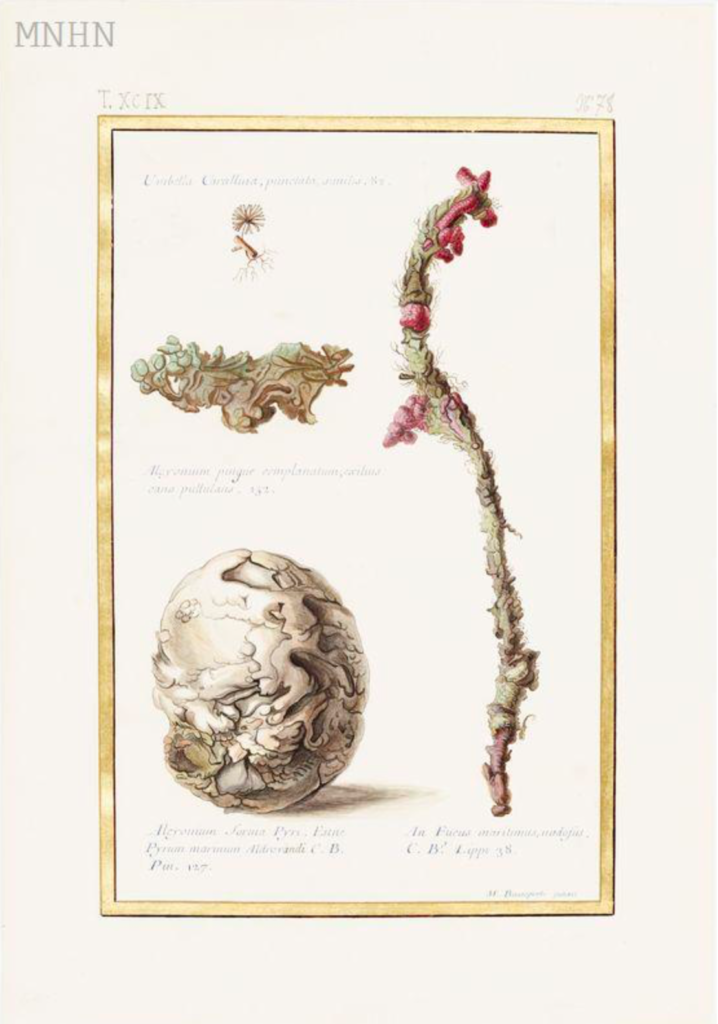

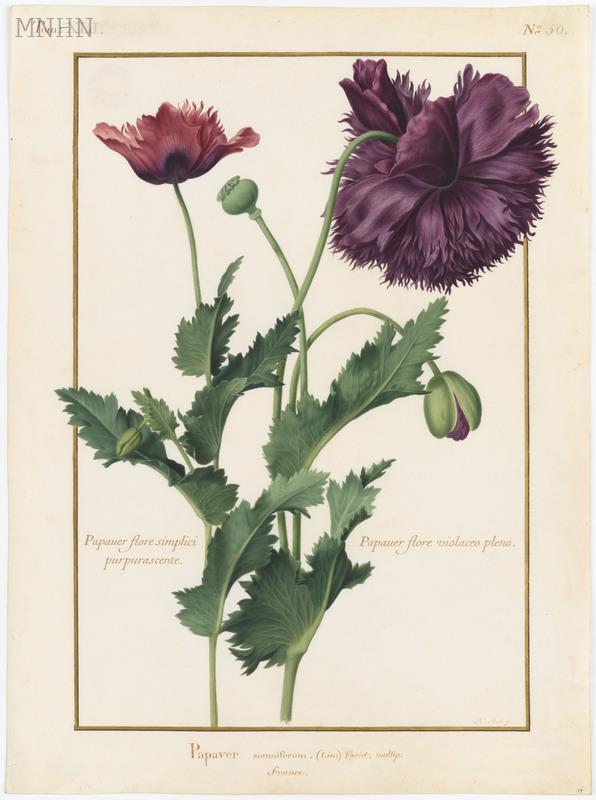

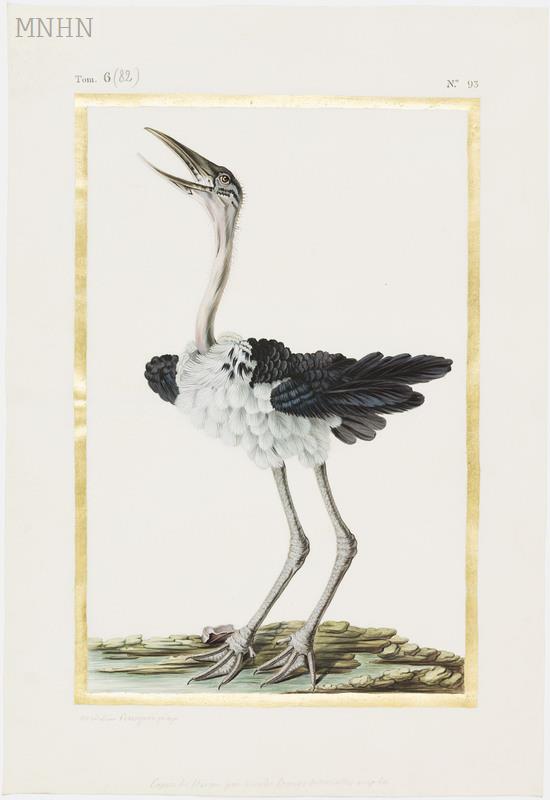

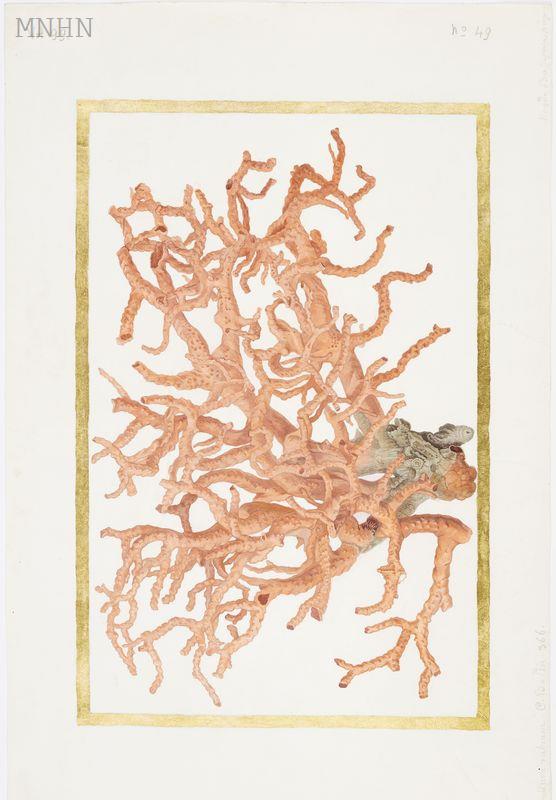

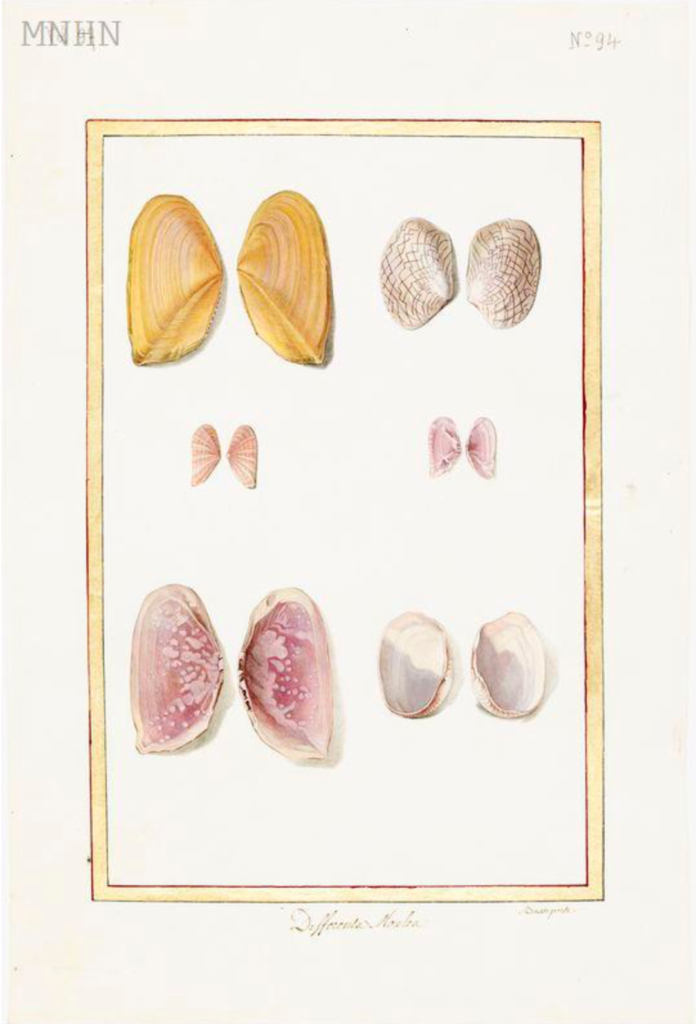

Her role in the King’s Garden, where she began training in natural history painting in her twenties and was employed until her death in 1780, positioned her uniquely as an artist-naturalist. She was responsible for visually documenting the plants, animals, coral, and shells in the royal collection (figs. 1–5). Basseporte was both an artist and a scientist, at a time when women were largely excluded from professional careers in either discipline.

The Scientific and the Decorative

Basseporte initially trained as a portraitist in the style of the incomparable Venetian pastellist Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757). From the moment at which she left that area of her practice behind, almost all of her work is scientific in character. The one surviving exception is a bound collection of decorative paintings called the Recueil de dessins de fleurs (Collection of Flower Illustrations), ca. 1750. This might have been acquired for the library of a wealthy collector, or used as a pattern book for amateur artists working in a variety of media. Though they are flower designs rather than scientific illustrations, Basseporte still reproduces each flower’s many constituent parts in a meticulous and knowledgeable manner. Their presentation is very similar to the paintings produced for the king’s collection, as the flower species, occasionally accompanied by insects, are framed in a gold border and set against a blank background. They are also composed of the same medium and materials: gouache (a type of watercolor) on vellum.

One painting within this collection, however, stands out as from the rest. That is folio 7 recto, in which two cut blossoms, a daffodil on the left and a hyacinth on the right, are bound together by a silk ribbon, tied in a bow at the base of the two stems (fig. 6). This piece of delicate pink fabric is the only instance of a non-natural material that I am aware of in Basseporte’s work. Pink is a color often associated with the rococo period in France and with Basseporte’s friend and collaborator, Madame de Pompadour (though the popular claim that Pompadour created a new shade of pink, rose Pompadour, has been proven false). As an aside, Pompadour’s favourite color was in fact blue, and I like to think it was the shade of blue that we see in the ribbons adorning her ensemble in a 1754 portrait which she commissioned from the artist Carle Van Loo (fig. 7).

Basseporte and Pompadour as Garden Cultivators

In this portrait, Pompadour (1721–1764), a prolific patron of the arts as well as Louis XV’s official mistress, stands enveloped in a lush outdoor garden setting. Her state of unfettered immersion in nature is emphasized by the floppy straw sun hat she has worn to protect her skin from the sun’s rays.

Much of what we know of Basseporte’s biography comes from a (sometimes unreliable) eulogy published a few months after the artist’s death. One important detail we learn from this document is that Pompadour would often request Basseporte’s expertise in painting portraits of flowers in bloom at her various countryside residences. According to the biography, Basseporte was often obliged to work in the heat of the sun in the gardens at the château de Bellevue, in order to capture blossoms at their peak. In a historical instance of women championing the causes of other women, Pompadour also petitioned the king for an increase to Basseporte’s wages.

Garlands and Flower Crowns in Portraiture

The small bouquet Basseporte presents in the Recueil illustration reminds me of other handmade flower arrangements that are assembled with ribbons. Beyond the adornment of dresses and other articles of clothing, ribbons were an integral component of a craft object created for festivals, ceremonies, and decor since antiquity: the garland, or, in its more diminutive and wearable form, the flower crown. These were made by tying cut flowers and leaves together using a piece of string (or occasionally ribbon), with ribbons attached to the end in a final flourish. From the mid-seventeenth through the early-eighteenth century, garlands and chaplets de fleurs appeared as frequent motifs or attributes in portraits of aristocratic women (figs. 8 and 9 ).

To my mind, the choice made by female sitters to have themselves portrayed in this way signals a desire to express their own cultivation through creative engagement with nature. In the early modern period, as today, the verb “to cultivate” possessed many meanings. One could cultivate the earth (cultiver la terre) as well as cultivate the mind (cultiver l’esprit). In these portraits, the ribbon serves as a mediator between the human (woman’s) touch and the natural world.

The Ribbon as a Gendered Object

The Encyclopédie, a pioneering attempt at a general compendium of knowledge published in France between 1751 and 1772, includes almost a dozen entries under the head word ribbon (ruban). Though the Encyclopédie also identifies ribbons in bookbinding, heraldry, and men’s wig-styling, the primary focus is on fashion, and ribbons are unequivocally categorized as ornaments worn by women. A Revolutionary-era book of hairstyles for ladies features ribbons not only garnishing wigs and garments but also in the very frames surrounding the women.

La Rubanière as a Gendered Profession

Ribbons were not only bought but also sold by women. The seventeenth-century artist Nicolas de Larmessin (1632–1694) became known for his printed engravings of tradespeople outfitted in their own wares. Bound in collections with titles like Habits des Métiers et Professions (Costumes of Trades and Professions), only a handful depict women professionals. One such characterization, however, is that of a Rubanière (woman ribbon seller, fig. 10). From the seventeenth century onward, ribbons (and rubanières) represented, to those critical of such things, the epitome of superfluous accessorizing and conspicuous consumption.

By the eighteenth century, rubanières could be included amongst the marchandes de modes, or fashion merchants. One of the most famous was Rose Bertin (1747–1813), the dressmaker to Queen Marie Antoinette (1755–1793, fig. 11). An early twentieth-century print portrait of Bertin emphasizes the prominence and priority given to ribbons in women’s haute couture (fig. 12).

The Artifice of Art

The singularity of the ribbon painting in Basseporte’s oeuvre cannot be overemphasized. Ribbons represent an alliance (albeit artificial) between humans and the natural world by means of a manufactured, consumer product. They signal not only the presence of a “woman’s touch,” but also the artificiality of the work itself. In a very clever way, Basseporte winks to the viewer by including an unnatural object so associated with a female-gendered material culture. She is saying, in the manner of the twentieth-century surrealist René Magritte, this is not a flower. It is but a painted reproduction. In doing so, she creates a tension between the organic and the manufactured, and points us to her authorship and authority as the image’s maker. Basseporte spent her career surrounded by male colleagues in the arts and sciences, and in this painting, she recalls and unites herself with her predecessors, women who engaged creatively with nature and embraced their own femininity as a means of empowerment.

Tori Champion is a PhD Candidate in the School of Art History at the University of St. Andrews. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Washington and a BS in Public Policy Analysis and International Business from the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. Her master’s thesis, submitted in the spring of 2021, was titled, “Le pinceau à la main: The Intertwined Lives and Careers of Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien.” Follow Tori on Instagram.

More Art Herstory posts to do with women natural history illustrators:

Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien: Finding the Natural in the Neoclassical, by Tori Champion

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte’s Hyacinths at the French Court, by Mary Creed

Barbara Regina Dietzsch: Enlightened Flower Painter, by Andaleeb Badiee Banta

Books, Blooms, Backer: The Life and Work of Catharina Backer, by Nina Reid

Curiosity and the Caterpillar: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Artistic Entomology, by Dr. Kay Etheridge

Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge, by Catherine Powell

Floral Still Life, 1726—A Masterpiece by Rachel Ruysch, by Lawrence W. Nichols

The Protofeminist Insects of Giovanna Garzoni and Maria Sibylla Merian, by Emma Steinkraus

Women in Zoological Art and Illustration, by Ann Sylph, Librarian of the Zoological Society of London

More Art Herstory posts to do with 18th-century women artists:

Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, Marquise de Grollier, by David Pullins

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist, Friend, Teacher, by Jessica L. Fripp

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Revolutionary Painter, by Paris Spies-Gans

Seductive Surfaces: Anne Vallayer-Coster’s Vase of Flowers and Conch Shell at the Met, by Kelsey Brosnan

A Short Reintroduction to the Life of Anna Dorothea Therbusch (1721–1782), by Christina K. Lindeman

Rosalba Carriera at The Frick Collection, by Xavier F. Salomon

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

“I feel again the violence of a curious desire”: Rare client testimonies on Rosalba Carriera’s erotic art, by Angela Oberer

Rediscovering the Once Visible: Eighteenth-Century Florentine Artist Violante Ferroni, by Ann Golob