Guest post by Kathryn Waters, DPhil student, Kellogg College, Oxford

The current Tate Britain exhibition Now You See Us is mammoth, spanning 400 years. It provides over a hundred women artists with a room of their own for only the second time in its history. The sheer number of people involved in the exhibition attests to the amount of work that has gone into it. It can, on a first visit, be a little overwhelming. Especially if one does not have the time, or space (as on my first visit), to properly take all the information in. Luckily it is well worth returning to.

Nonetheless, it raises questions about why such exhibitions are still required. It is more than fifty years since Linda Nochlin’s ground-breaking article, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (ARTnews, 1971) and the resulting 1976 retrospective Women Artists: 1550–1950 in the United States. And yet women continue to be written out of art history, or considered to be an inferior sub-set of artists.

This new retrospective is logically set out in chronological order. The curators have carefully set out some themes for each room, which helps visitors navigate the size of the exhibition.

Written out of history

The exhibition demonstrates that women built successful, professional careers as artists throughout this period. The issue, as the Tate demonstrates, is that professional women artists were consistently written out of art history. The first room makes this point using the alleged miniatures of Susanna Horenbout (c.1503–before 1554) and Levina Teerlinc (1510–1576). There are contemporary accounts of both women’s work as professional artists in the Tudor court. Nonetheless, it is difficult to be certain that works now attributed to them are theirs. For example, Teerlinc is recorded as having given Queen Elizabeth I several works of art as New Year’s gifts, but the works themselves do not appear to have survived. Of the miniatures attributed to Teerlinc in the exhibition, there remains considerable doubt over that attribution.

Inserting themselves into the pictorial narrative

And yet, in a theme which pervades the exhibition, often the female artist becomes the subject matter herself. Women artists stare back at the viewer in self-portraits throughout. Examples range from Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) who paints herself as the figure of “Invention” in the first painting of the exhibition, to Gwen John’s (1876–1939) self-portrait in the exhibition’s final room.

Sarah Biffin (1784–1850), born without arms, painted herself using only her mouth and shoulder.

Patriarchal Attitudes

As the viewer moves through the exhibition, the stories behind the paintings are told in the accompanying descriptions. These accounts often highlight the patriarchal attitudes which have impeded the recognition of professional female artists over the centuries. There is no moralizing here. The wall text simply presents the facts for the reader to take as they will. For example, the physician Messenger Mosley commissioned Mary Black (1737–1814) to paint his portrait. However, he refused to pay her price despite it being half what a male artist of the time would have charged. He claimed, in a letter to his cousin, that she was “saucy” for having asked for payment. He even labelled her “a slut.”

Women’s art as “amusement”

As the exhibition emphasizes, women’s contribution to art was often diminished by its association with “lesser” artforms, such as watercolors, needlework and paintings of flowers. The Royal Academy considered such work to be for amusement only, rather than serious professional, artistic endeavor. The striking thing about, say, the complex needlework of Mary Knowles (1733–1807) and Mary Linwood (1755–1845) is the highly skilled nature of their work. These women artists were also adept at navigating professional networks and securing a living from their art. In 1771, Queen Charlotte paid Mary Knowles £800 to produce a needlework copy of a portrait of George III. Mary Linwood’s exhibition in Hanover Square received 40,000 visitors in 1798. This puts her work on a level with the Royal Academy exhibitions which banned such needlework art.

Mary Moser (1744–1819), whose primary subject matter was flowers, was not afforded the same level of professional renown as Angelica Kauffman, who painted classical scenes. This is despite both painters being founding members of the Royal Academy. The careers of other artists who specialised in floral subjects, such as Mary Delany (1700–88) and Clara Maria Pope (c.1767–1838), suffered the same fate, notwithstanding the detailed scientific skill and accuracy that characterizes their work.

War Paintings

The show also includes several examples of women painting on the theme of war. This is despite such work being traditionally thought to be the preserve of male artists. Elizabeth Butler’s (1846–1933) The Roll Call (1874), for which she achieved great renown, depicts a scene from the Crimean War. While the heat and structure of munitions factories forms the subject matter of the works on display by Anna Airy (1892–1964), the first official female war artist.

Radical women and art

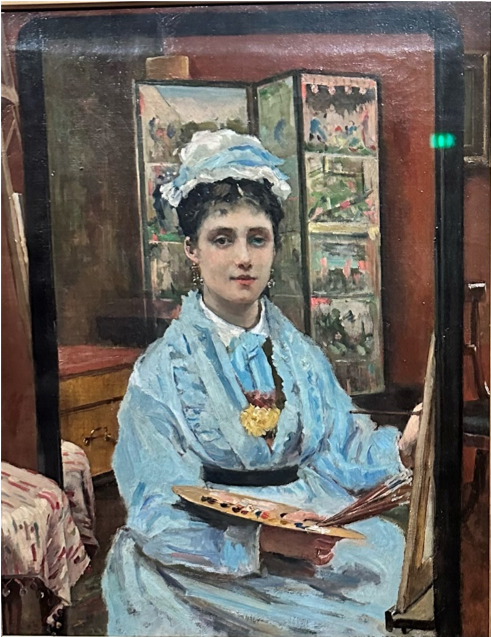

Now You See Us also charts women’s campaigns for formal training and to obtain membership of the professional institutions. As the Tate notes, access to these resources opened opportunities, including networking, for their male counterparts. Lack of access impeded the attempts of women to be treated as successful, professional artists. Pioneers in this respect are well-represented in the exhibition. In particular, the Tate has recently acquired a self-portrait of Louise Jopling (1843–1933), Through the Looking Glass (1875).

Jopling was the first woman elected to the Royal Society of British Artists. She promoted feminist causes, including art education for women, and eventually founded her own school of art. However, while she produced over 750 works of art, the majority of these are now lost.

Ethel Wright’s (c.1866–1939) sumptuous portrait of the suffragist Una Dugdale Duval (1879–1975) shows her as a cultured, attractive woman of poise. It is a fitting riposte to the conservative press’s depiction on suffragists as “unkempt, unattractive harridans” (exhibition catalog, p.197). When she married in 1912, Dugdale refused to promise to obey her husband. In 1913 she wrote a pamphlet, Love and Honour but Not Obey, outlining her reasons for doing so (also on display in the exhibition next to her portrait).

The Intersectional Elephant in the Room

While the exhibition creates an impressive space for representing women’s art history, it demonstrates there is still work to do regarding providing an intersectional perspective. Only two of the artists are non-white: Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907) and Zaïda Ben-Yusuf (1869–1933). The Tate has also chosen to concentrate on the artist’s professional status, rather than include too much personal biography in its descriptions. On occasion, this has the unintended consequence of erasing the perspective of queer and gender non-conforming artists, for example in the case of Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) and Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908).

One notable exception to this is the delightful story of Clare (“Tony”) Atwood (1866–1962) who lived in a ménage à trois with Christabel Marshall (also known as Christopher St. John) and Edith Craig. Her painting in the exhibition, The Terrace outside the Priest’s House (1919), shows the simple domesticity of their arrangement.

Clearly, the issues highlighted by the Tate with respect to women’s recognition within art history apply to women from marginalized groups as well. However, they will have been affected even more greatly than the predominantly white, middle- and upper-class women the exhibition includes. I do think the Tate has missed an opportunity to face into these questions of intersectionality more explicitly. But they do themselves acknowledge there is more work to be done in this respect.

What next?

In her introductory foreword to the exhibition catalog (pp.17–19), “Travelling Hopefully,” Pamela Garrish Nunn notes that the canon itself remains unchanged despite the attention women artists have been afforded since the 1970s. Nunn makes a valid point that retrospectives such as this are of long-term value only if we contemporaneously challenge the way we value women’s art. We need to dismantle the supremacy of men’s art and how that informs the definition of what “good” art is.

This is even more important when considering questions of intersectionality. Art institutions must start to feature women of all kinds in their permanent collections, as the Tate is doing. Exhibitions like Now You See Us absolutely play a very important role in holding us to account on such issues. The wealth of new research undertaken by such exhibitions as this one will increase awareness and recognition of the work of women artists. Hopefully in another 50 years’ time, we will see a retrospective that demonstrates we have been successful in that aim.

Now You See Us is on at Tate Britain through October 13, 2024. A paperback exhibition catalog accompanies the show.

Kathryn Waters is studying part-time at Kellogg College, Oxford for the DPhil Literature & Arts. Kathryn has broad research interests in literary women in the mid-nineteenth century. In particular, she is interested in the circles of writers, artists, actresses and other professional women involved in the various women’s rights movements at that time. Her interdisciplinary DPhil thesis considers the appropriation of Shakespeare by such women. She considers their appropriation in the context of the mid-nineteenth century women’s movement for formal education. Her thesis focuses on both the performance of, and women’s writing on, Shakespeare’s plays and characters in this period. Kathryn is also a solicitor specializing in banking and finance law.

Other Art Herstory blog posts you might enjoy:

Finding Catherine Read, by Adam Busciakiewicz

British Women Artist-Activists at The Clark Art Institute, by Erika Gaffney

The Lost Works of Susanna Horenbout, Female Artist at the Tudor Court, by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Susannah Penelope Rosse: Painting for Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century England, by Anna Pratley

Museum Exhibitions about Historic Women Artists: 2024

Helen Allingham’s Country Cottages: Subverting the Stereotype, by Amy Lim

An Introduction to Minnie Jane Hardman, by Hannah Lyons

Angelica Kauffman: Art, Music and Poetry, by Ellice Wu

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Mary Linwood’s Balancing Act, by Heidi A. Strobel

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Levina Teerlinc, Illuminator at the Tudor Court, by Louisa Woodville

Angelica Kauffmann: Grace and Strength, by Anita V. Sganzerla

Susanna Horenbout, Courtier and Artist, by Kathleen E. Kennedy

Mary Beale (1633–1699) and the Hubris of Transcription, by Helen Draper

Paper Portraits: The Self-Fashioning of Esther Inglis, by Georgianna Ziegler

“Black-works, white-works, colours all”: Finding Susanna Perwich in her Seventeenth-Century Embroidered Cabinet, by Isabella Rosner

“Bright Souls”: A London Exhibition Celebrating Mary Beale, Joan Carlile, and Anne Killigrew, by Laura Gowing