Guest post by Alessandra Masu, author, journalist and art historian

Finally, Italy also has a museum truly open to women artists: Museo Ottocento Bologna. It is a museum dedicated to Bolognese artists (men and women) of nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whose mission is to fill the gender gap of representation and visibility of women artists in public collections. The museum was inaugurated in April 2023 not in the capital, Rome, but in the most progressive city and center of women studies in Italy: Bologna. Home to the oldest university in Europe (founded in 1088), and the most culturally and politically progressive city of the Italian Republic (1946), the Bolognese school of art history has played a key role in researching and re-evaluating the contribution of women in the arts. Thanks to Professor Vera Fortunati, a pioneer in the field, Bologna is the one university faculty in Italy where gender art history is taught.

The exhibit activity of the new museum started last September with a focus exhibition of the painting Giovinezza (Youth), by the Deco artist and designer Emma Bonazzi (Bologna, 1881–1959).

Until February 25, 2024, Museo Ottocento Bologna hosts the first monographic exhibition on the first woman admitted to the Academy of Bologna in 1804, and to the Academy of Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 1811: Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840. Una pittrice bolognese nella Roma di Canova (A Bolognese paintress in Canova’s Rome). The exhibition is curated by the Director of Museo Ottocento, the art historian and archivist Francesca Sinigaglia, and by Gargalli specialist, Ilaria Chia.

Carlotta Gargalli (Bologna, 1788–Rome, 1840) is part of a tradition of Bolognese women artists that began at the end of the fifteenth century with the sculptress Properzia de’ Rossi, and continued with Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani. In 1821, the proto-feminist Irish writer Sydney, Lady Morgan (Dublin, 1781–London, 1859) visited the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna and met Gargalli while working on an imitation copy of Raphael’s Saint Cecilia. She wrote: “In the Gallery of the Institute, we frequently found the young and interesting artist Signora Carlotta Gargalli, the Elisabetta Sirani of the day.” Indeed Gargalli was the first woman to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna, and the only one for the next seventy years. Unlike Sirani, she studied and traveled outside of Bologna. Like Lavinia Fontana, she worked in Rome as an independent professional artist.

The only woman to attend Bologna’s Academy in 1804

Carlotta Gargalli was trained by her artist father, Filippo, in drawing and painting. Filippo Gargalli (Bologna, 1750–1835) was a successful portrait painter and his Portrait of Maria Brizzi Giorgi (Fig. 1) appears in the first section of the exhibition.

Madam Giorgi was an accomplished Bolognese composer and musician who was an élite figure during the Napoleonic era as well as muse and mentor of the Italian composer Gioacchino Rossini. This painting is a meaningful example to contextualize Carlotta Gargalli’s early training in her father’s studio. In 1804, she was the only woman attending the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna.

The exhibition offers two of Gargalli’s early works: the Portrait of Andrea Pizzoli (1806; Fig. 2), where a few details recall Gandolfi’s eighteenth-century style even though a general neoclassical taste is evident, and Artemisia, a painting which earned her the 1807 Piccolo Concorso Curlandese award from the Academy of Fine Arts (Fig. 3).

A Bolognese paintress in Canova’s Rome

The second section of the exhibition showcases Gargalli’s work from her first period in Rome. In 1811, after many vicissitudes, Carlotta obtained a special authorisation to attend the Academy of Rome at Palazzo Venezia. On November 11, she arrived in Rome and began her three-year scholarship.

In Rome she contacted the most important local artists, including Antonio Canova, and started a friendship with one of the few women artists active in early 1800 Rome: Bianca Milesi (1790–1849; see her portrait by Gaspare Landi at left of Fig. 4, and at right in Fig. 5).

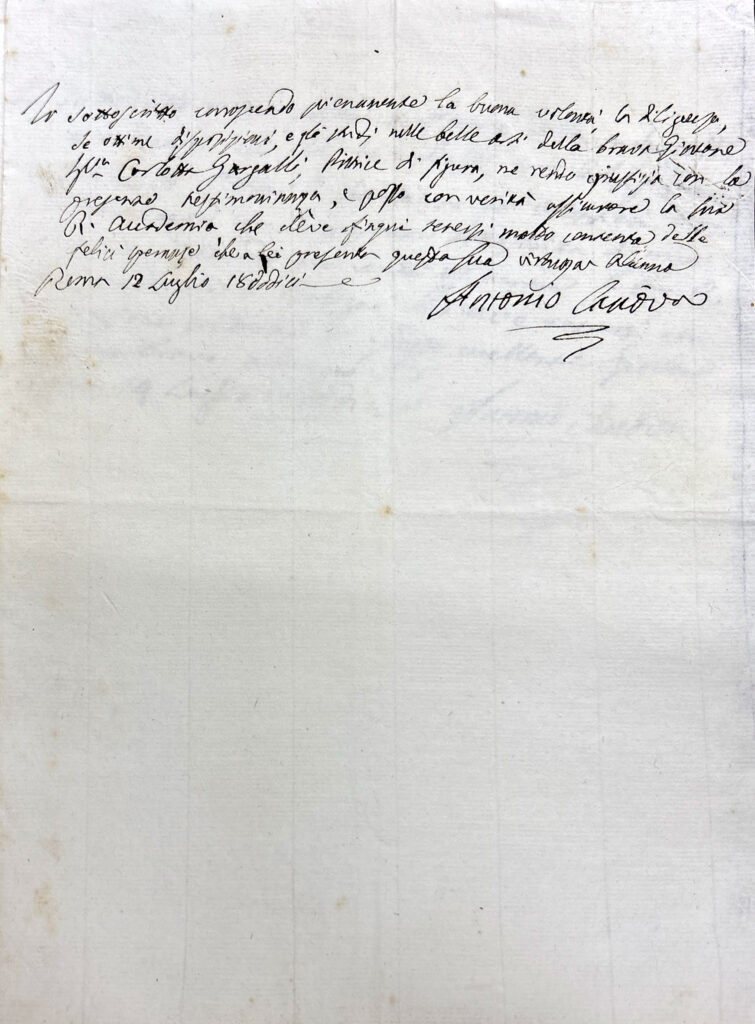

During her scholarship, Gargalli had to submit a sample painting that could prove her artistic progress to a Committee in Bologna every year. At the end of her first year, she sent a Portrait of a Clergyman, a copy after Moretto suggested by Canova, who owned the original work. Her version received a positive judgement. In March 1812, in order to justify a delay in her artistic production, Gargalli reported the Bolognese Academy she had some health issues. In July Canova wrote a positive reassurance statement (Fig. 6).

However, she still managed to send a large painting depicting Ajax (Fig. 7). This work faced harsh criticism because of its disproportion.

Following some bureaucratic hassle and the closure of the Academy of Rome due to political turmoil, Carlotta Gargalli completed her final scholarship sample back in Bologna. Pyrrhus threatening to kill Astyanax (Fig. 8) earned her a reward of 500 Liras. The painting clearly shows the influence of Jacques Louis David, Napoleon’s official painter. They both went into exile after the defeat of Waterloo in May 1815.

1815–1840: a studio of her own in Bologna, and back to Rome

The third section of the exhibition is focused on Gargalli’s production after 1815, as the painter went back to Bologna. Here, in 1816 she opened her studio where she specialised in portraiture and imitations of antique works. A masterpiece of the first genre is the Portrait of de’ Bianchi Family (Fig. 9).

Carlotta Gargalli found her own voice by mixing new trends—such as the style of Angelika Kaufmann—with references to the traditional Bolognese school, in particular Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani. The painting was exhibited in 1817 in the Academy of Fine Arts, where it received considerable appreciation.

On January 7, 1821, Gargalli married the physician Carlo Rovinetti. On the same day, after two years of waiting, she was finally appointed Honorary Member of the Bolognese Academy. In fact, she was included since the number of Academy members was below the minimum threshold.

The recently restored Portrait of Gaetano Albicini (Fig. 10), painted in 1820, followed neoclassical portraiture standards. It is a sober and essential painting, in which the young boy has a lively gaze, while his rosy cheeks and full lips recall the earlier Portrait of Andrea Pizzoli. In the decade 1827–1836 the artist lost her parents (her father Filippo left her all the contents of his studio), her beloved husband (1827) and their daughter, Sofia (1836). After this last loss, Gargalli married Antonio Bassi, a Faenza-based merchant, and moved to Rome. She continued to work as a portrait painter, but focused her business on the production of small copies from prototypes of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Raphael, Correggio).

Carlotta Gargalli died in Rome on December 4, 1840.

Carlotta Gargalli 1788–1840. Una pittrice bolognese nella Roma di Canova is on at Museo Ottocento Bologna through February 25, 2024 (extended from January 7).

Author, journalist and art historian Alessandra Masu loves to unearth the stories of overlooked women and collects art created by women from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century. Alessandra’s writing has appeared in many places in print including D, la Repubblica’s weekly style magazine. As an art historian, she has contributed to several exhibitions and art publications and is the author of the historical novel Lena, che è donna di Caravaggio (EtGraphiae, 2013). In 2020, with Ginevra Bentivoglio Editoria, Alessandra published Perchè io non voglio star più a questa vita. La voce di Beatrice Cenci dai documenti conservati negli archivi romani. In 2016 Alessandra, in collaboration with art historians Consuelo Lollobrigida and Beatrice De Ruggieri, founded the cultural association Artemisia Gentileschi, which is based in Rome. On March 8, International Women’s Day 2022, the association launched the Artemisie Museum project (https://www.artemisie.com/the-virtual-museum), the first virtual museum-database of women in the arts.

More Art Herstory exhibition reviews:

Making Her Mark Leaves its Mark at the Art Gallery of Ontario, by Isabelle Hawkins

Female Artists and their Remarkable Careers: An Appeal to Rethink Art History, by Jenny Körber

Making Her Mark, An Essential Corrective in the History of Art, by Chadd Scott

Masters and Sisters in Arts, by Jitske Jasperse

Reflections on Making Her Mark at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Erika Gaffney

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, A Review, by Alice M. Rudy Price

Material Re-Enchantments: A Review of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, by Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Rosa Bonheur—Practice Makes Perfect, by Ien G.M. van der Pol

The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon, by Suzanne Singletary

Thérèse Schwartze (1851–1918), by Ien G.M. van der Pol

More Art Herstory posts about 19th-century women artists:

Illuminating Sarah Cole, by Kristen Marchetti

The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer, by Thomas Cooper

Marie Spartali Stillman’s The Last Sight of Fiammetta, by Margaretta S. Frederick

Visual Feasts: The Art of Sarah Mapps Douglass, by Erika Viola

Evelyn De Morgan: Painting Truth and Beauty, by Sarah Hardy

Portraying May Alcott Nieriker, by Julia Dabbs

The Ongoing Revival of Matilda Browne, American Impressionist, by Alexandra Kiely

The Theatrical Wonders of Jeanne Paquin’s Belle Époque Parisienne, by Julia Westerman

Also by Alessandra Masu:

A Home for Women Artists in Rome

Roma Pittrice: Women Artists at Work in Rome Between the Sixteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Judith’s Challenge, from Lavinia Fontana to Artemisia Gentileschi

Plautilla Bricci: A Painter & “Architettrice” in Seventeenth-century Rome